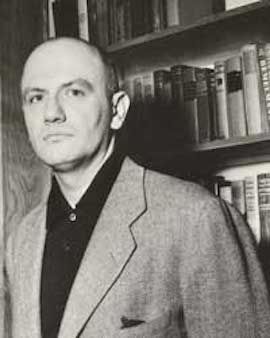

Thomas Berger: A Celebration

Thomas Berger has died, but he always said it was all about the work, not the life.

By Brooks LandonJuly 26, 2014

AN OLD FRIEND HAS DIED and I don’t really know what to say. I’ve written two books and a bunch of articles about Thomas Berger’s fiction, and I exchanged letters and emails with him for nearly 40 years, so I should have something worth saying about the recent death of one of America’s great novelists. But I’m not sure what. Worse, I’ve been invited to write an appreciation of my dead friend and, in so many ways, my mentor. So, what’s an appreciation? I appreciate consideration, I appreciate kindness, I appreciate good cooking, I appreciate good weather, I appreciate fine writing — but none of those “appreciations” seems remotely appropriate to the loss I feel. A loss for myself, sure, but also a loss for so many others who feel as I do about Thomas Berger’s greatness and genius. Even more, I feel the loss for the readers who haven’t discovered Berger, so aren’t yet aware of what a loss they have suffered.

Maybe I should start by setting the record straight in a few ways. Tom valued precision, so let me be precise. First of all, I am most certainly NOT, as The New York Times would have it, “Berger’s biographer.” Nor is anyone else. Tom had no patience with those who wanted to focus on his life rather than on his fiction, and, while I did have to record some basic dates and facts about his life in my studies of his novels, I tried to honor his scruple and succeeded in learning very, very little about his personal life. Indeed, the only thing I have to offer as a putative “Berger biographer” is that he felt the no-frills L.L.Bean Jean Belt, which sold in the 1970s for much less than it does now, was a pretty good deal.

I learned that sitting in Zulfikar Ghose’s backyard in the hills above Austin, Texas, on the second of the only two days I ever spent in Tom’s presence. He was visiting Zulf, a creative writing professor in the University of Texas English Department and one of his close friends. Berger dedicated his Regiment of Women (1973) to him, and Zulf, a justly celebrated writer himself, had written the first volume of his The Incredible Brazilian (1972) as something of a playful response to Berger’s Little Big Man (1964). The day before Berger had visited one of Zulf’s classes, where Zulf had inflicted upon him a grad school paper I had written on Killing Time (1967). That paper and the two days in which I listened to Tom talk about his writing (and his belt) eventually led to a dissertation and a career writing about Berger’s 23 novels and smattering of short stories. It also led to nearly 40 years of correspondence with him and one phone call. But, the second thing I need to set straight is that Zulfikar Ghose would know what to say about Tom’s life, and anyone interested in Berger should seek out Zulf’s precise and insightful writing about his close friend. Head to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, where Zulf’s long correspondence with Tom is housed. Zulf believed in the primacy of style, explaining, “Novels which stand on their style alone win readers slowly, in little bands here and there, until the work becomes one of the layers which compose human consciousness.” It always seemed to me that Tom and Zulf fit the “Separated at Birth” meme perfectly — they shared remarkably similar views of the world and of writing. Zulf should be the one writing this.

Or, if not Zulf, Jonathan Lethem or Tom Perrotta or any of a dozen or so distinguished writers, critics, and scholars, such as David W. Madden, who have detailed in print their great admiration for Berger’s fiction and their indignation that his work had not been more widely read and honored. Lethem knew Tom much as I did, mainly through his novels and his correspondence. And he has written eloquently about that friendship:

Lethem has also a number of times written insightfully about Berger’s fiction, perhaps most thoroughly in his introduction to the 2003 reissue of one of Berger’s most hard-edged novels, Meeting Evil.

Tom Perrotta has also felt the magic of Berger’s fiction, and once took a writing class taught by Berger. In his NPR contribution to “You Must Read This” Perrotta details his fondness for Berger’s 1980 novel Neighbors, a book such as Kafka might have written had he lived in an American suburb and had a much stronger sense of humor. He does an infinitely better job of suggesting the numerous appeals of that novel than did the troubled Belushi/Aykroyd movie made from it in 1981 (not to be confused with Seth Rogen’s 2014 flick with the same title). Perrotta described Tom as “the funniest serious writer in America,” and that’s not a bad start on identifying Berger’s unique and radical sensibility.

The movie made from Neighbors was at least odd, and on his visit to the set Berger enjoyed “meeting the boys.” But the 2012 movie based on Meeting Evil, which starred Samuel Jackson and Luke Wilson, was just bad. A much better representation of a Berger novel was the 1989 The Feud, directed by Bill D’Elia and featuring Rene Auberjonois. Berger’s novel of that title would have (and should have) won the 1984 Pulitzer Prize had not the administrators of the prize overruled the choice of the judge’s panel and awarded the prize to William Kennedy’s Ironweed. The movie based on The Feud isn’t bad; the novel is nearly perfect.

Of course, the movie Berger will always be most associated with is Arthur Penn’s 1970 Little Big Man, a masterful film featuring wonderful performances by Dustin Hoffman, Chief Dan George, Faye Dunaway, and Richard Mulligan. Tom’s only regret about that delightful film is that before it was made he passed up a chance to share in its potential earnings in favor of the immediate hard cash needed to renew Penn’s option on film rights to the 1964 novel, a decision worthy of the disastrous decision-making of Carl Reinhart, protagonist of Berger’s highly praised Reinhart Series of four novels: Crazy in Berlin (1958), Reinhart in Love (1962), Vital Parts (1970), and Reinhart’s Women (1981). The movie is brilliant; the novel is one of the enduring classics of American Literature. And The Return of Little Big Man (1999) is that rare sequel that recaptures most of the magic of its predecessor, particularly Jack Crabb’s voice, while offering a window onto many of the changes in its author’s thinking and in the concerns of the world during the 35 years since 1964. A 50th anniversary edition of Little Big Man is reported to be in the works.

I see I’ve strayed from my announced intent to set the record straight, something I didn’t manage even at book length — twice — and so I don’t like my chances now, either.

Still, for the record, Tom did NOT satirize, much less parody, the genres or literary traditions to which his novels, no two alike, respond. Tom called his takes on classic genres “celebrations,” and insisted that he wrote not to make fun of but to honor each genre or classic formula. I believe him — and you will too if you read his novels.

He was NOT a “comic novelist.” He vehemently bridled at being called one. He insisted that to be comic was never his intent, and he even claimed that he had tried in later years “to be grimmer and grimmer and grimmer,” but the inescapable fact remains that much of his fiction is hilarious. Michael Malone was on to something when he specified that Berger was “a writer of comedy (as opposed to comic writer),” but Jonathan Lethem absolutely nailed it when he observed: “Berger isn’t comic. He, like life, is merely, and hugely, fucking funny.”

And he was NOT a recluse, an absurd claim. In a time less invested in the attention economy of celebrity, Tom might with some accuracy have been described as “private,” but he generously made himself available to those who understood that his preferred form of engagement with the world was writing. (Every letter or email from Thomas Berger underscored his claim that he would compose a note to the milkman with the same care he exercised in writing a novel, and he hewed to that practice even in his last years when his body started to fail: “That’s my report as of Memorial Day, which in my youth, when all the schoolchildren marched through town wearing paper hats and brandishing miniature US flags, was called Decoration Day. If I took a step now without artificial support I’d fall on my face: indeed, I’ve tested that theory, and I did.”) He freely gave interviews, although, like Nabokov, he preferred them in writing. He had many friends and many have written about his affability. Perrotta’s memory of the writing class Tom taught (and Berger visited a number of writing classes, even making it to Iowa City) is NOT the picture of a recluse:

Every day, Berger would arrive in class chuckling about something that had happened on the way over, some confusion over parking regulations or an unexpectedly delightful phrase he’d encountered on a menu. Listening to him, you got the sense that every little thing you did — a trip to the supermarket, a simple home repair — could be an excellent comic misadventure if you just looked at it in the right way and had no expectations beyond the certainty that everything you did was doomed to go horribly and hilariously awry. So why not go ahead and enjoy it?

Some years ago in a Washington Post interview with David Streitfeld, Berger, with disarming honesty, tried to put to rest claims of his reclusivity:

The plain truth is that I would shamelessly suck up to anybody who might further my career (which indeed seems to be precisely what I’m doing here), but in the far-off days when I went public in quest of self-aggrandizement, I encountered only other opportunists, mes semblables et frères, who expected to do to me what I had intended to do to them.

One of the last articles to appear about Tom before his death was “Reinhart At Home,” written by Tim Cavanaugh and published in the June 2, 2014 National Review. It began, “One of America’s last literary lions has stopped writing novels, and hardly anybody has noticed.” (Along with Cavanaugh, Lethem, and numerous other Berger readers, I can only hope that the trusted advisors who talked Tom out of publishing what would have been his 24th novel had not lost a step in their critical acumen, since it is nearly inconceivable to me that Tom had lost a step in his writing.) Cavanaugh did his homework for his article, including getting in touch with Berger and several of his friends. He writes with the distinctive pride of a Berger reader, revealing in numerous ways a deep understanding of Berger’s sensibility. He closed his piece with the now sadly dated claim — but timeless sentiment — that “we are lucky to have Berger, with his bemused intelligence, his eye for reality’s essential strangeness, still with us on earth.”

When Chief Dan George’s plans for a dramatic death are foiled by the inconvenient fact that he doesn’t manage to die at the planned moment, in George’s unforgettable role as Old Lodge Skins, he utters what is certainly the most memorable line from the film version of Little Big Man, a line not to be found in the novel, where Old Lodge Skins dies in a scene that caused Berger to weep as he wrote it: “Well, sometimes the magic works, sometimes it doesn’t.” In the life and writing of Thomas Berger, the magic almost always did work.

For all of their foibles, disastrous misadventures, and self-deceiving blindnesses, Berger’s characters, such as the indomitable Reinhart (whose misadventures we follow in four novels spanning from his youth as a GI in Berlin at the end of World War II to his hard-won equanimity in late middle age), the conflicted Gawain and Arthur of Arthur Rex (where Camelot is undone by complexity), the irrepressible and indestructible Jack Crabb, the humorously confused Earl Keys of Neighbors, the hapless Russell Wren of Who Is Teddy Villanova?, and even the terribly nice murderer Joe Detweiler, of Killing Time, all do their best, and all can help a reader through tough times. I’ve tried to tell anyone who would listen what knowing Thomas Berger and reading his quietly profound fiction has meant to me, thanking Tom for giving me more hours of reading and rereading, thinking, and writing pleasure than I could ever count. From Tom I received an invaluable education, the intellectual joy of my life, an attitude toward the language that constructs the world, and maybe even a smattering of secondhand wisdom. Tom is gone, but his gift to us remains, wrapped between the covers of his 23 novels, waiting patiently in the amazing and frequently serpentine syntax of his exquisite sentences, promising to introduce or reintroduce us to the unique sensibility of an American literary giant.

¤

Brooks Landon teaches in the English Department of the University of Iowa.

LARB Contributor

Brooks Landon teaches at the University of Iowa, and has written books on Thomas Berger, science fiction, and writing sentences. His collection of 24 lectures, Building Great Sentences, is available from The Teaching Company.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Brave New Perspective of Suburbia: Katherine Bucknell’s "+1"

A view of suburbia through rose-colored glasses …

Outborough Destiny: Jonathan Lethem’s “Dissident Gardens”

Jonathan Lethem’s Dissident Gardens is an assured, expert literary performance by one of our most important writers.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!