“This Feeling Will Never Leave Me”: On Yelena and Galina Lembersky’s “Like a Drop of Ink in a Downpour”

Herb Randall plunges into “Like a Drop of Ink in a Downpour,” a memoir of art, imprisonment, and emigration by Yelena and Galina Lembersky.

By Herb RandallJanuary 18, 2022

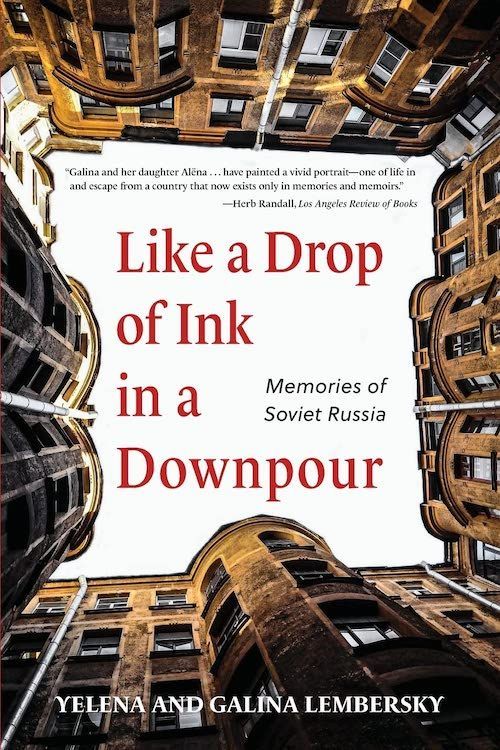

Like a Drop of Ink in a Downpour by Yelena Lembersky and Galina Lembersky. Cherry Orchard Books. 220 pages.

A GRUESOME DRAGONFLY duel. Rusty bullets found in the woods while playing war. Grandmother’s veins turning blue while painfully transforming summer cabbages into winter sauerkraut. Creaky wooden stairs from the first synagogue visit. Kindly neighborhood fairies keeping a watchful eye over it all.

These images shimmer through Yelena and Galina Lembersky’s Like a Drop of Ink in a Downpour just as crimson, cobalt, and cadmium yellow hues danced on the muralled walls of the Leningrad studio of the artist Felix Lembersky, father and grandfather of the authors. Like Felix, Galina and her daughter Alëna (Yelena’s preferred diminutive) have painted a vivid portrait — one of life in and escape from a country that now exists only in memories and memoirs. Their family tenet is that “art comes before anything else,” and the book serves as a harrowing illustration of the high price such a devotion to art can extract, while also providing hope to sustain the devotion.

Alëna’s kaleidoscopic memories of her childhood are full of portent for the difficulties she will face, yet sweetly nostalgic. Born in 1969 in Leningrad, she was not yet a teenager when her mother, Galina, was convicted and imprisoned in a meritless petty corruption case, and she was taken to live with a family friend. The trauma of uprooting hangs over these pages, whether it’s a daughter’s account of the alienation she suffered while her mother was taken away from her, a mother lamenting her daughter’s fate while cut off from her in prison and struggling to still be involved in her life, or the struggle to rescue a Soviet artist’s paintings and bring them to the United States.

The deeply felt obligation to preserve Felix’s paintings and exhibit them to the public drives the family’s decision to emigrate. Escape from the Soviet Union during its extended death rattle of the 1980s was made possible for Alëna and Galina by the policy of allowing Russian Jews to emigrate, which was won at great cost and not applied without pain. “Only traitors leave our motherland,” Alëna’s schoolteacher tells her, and the conflict she feels during their lengthy preparations to leave is the least of her problems: the suspicion of potential émigrés leads directly to her mother’s imprisonment and their subsequent refusenik status. Their struggles are a stark reminder that the oppression and terror of Soviet citizens did not end with Stalin’s death. The infamous mass executions and wholesale deportations may have ceased long before Galina’s trial in 1981, but the denunciations born of jealousy or personal score-settling, sham trials, surveillance, disregard for the welfare of detainees and their children, and blackmail by the secret police persisted until the fall of the Soviet Union. The injustices became more cynical and sordid as neither the nation’s leaders nor its citizens had much faith left in the communist project.

Yelena refers to their preparation to emigrate as “a time to uproot,” in a nod to the notorious Soviet epithet of “rootless cosmopolitans” hissed at Jewish families. Yet Alëna’s and Galina’s Jewish identity is as foreign to them as it is suspect to the society that surrounds them. Although Felix Lembersky is best known today for his series of paintings of the notorious Babi Yar massacre of Kyivan Jews by the Nazis, his overtly Jewish work was suppressed in the Soviet Union, as was any discussion of history that might foster a collective consciousness outside of the state’s plans. Felix’s coded, subversive inclusion of Jewish symbols in his other paintings also reflects the method by which he and Galina’s mother transmitted their heritage to their children and grandchildren. Alëna remembers seeing one of the Babi Yar paintings that visitors to their shared apartment made secretive pilgrimages to view: “And here are my grandfather’s canvases, the rope bridges I can take to find my way to what cannot be put in words.” Galina and Alëna’s journey from hushed whisperings at home about the word “Jew” to furtive, mystified visits to synagogues, clandestine Hebrew lessons, and eventually full acceptance of their faith is one of the strongest strands in their memoir, a fulfillment of Alëna’s grandfather’s artistic and moral mission.

The sense of displacement, of existing in the ravines between conflicting identities and places is reinforced by the unusual structure of the memoir. Alëna narrates the first and final sections, which are interrupted by Galina’s story, addressed directly to her daughter. Alëna recorded her mother’s recollections from 2012 to 2020, and together they fill gaps in their respective narratives, each one contributing painful memories that the other is unable to face. Alëna recounts her candid impressions of her mother as prisoner during their first permitted family visit, from rotting teeth to a new proclivity for profanity, while Galina, almost like a child, draws a veil over it: “I was afraid of our meeting. That visit … No, I will not talk about it.” On this and other occasions, the lines between the identity of mother and daughter blur, as young Alëna must grapple with situations no child should bear, and as Galina becomes dependent on her daughter to sustain her through imprisonment and rehabilitation. As an adult, Alëna reflects on her perceived dual role, and how her mother was “a child, whom I failed to protect. My child-Mama. I don’t yet know what is happening, except that disaster is coming. This feeling will never leave me. It will grow with the years and take over my happiest moments — our family holidays, the birth of my children.” Despite their separation and straitened circumstances, this maternal bond, if sometimes inverted, sustains Alëna and Galina through their separation and much-delayed emigration.

“Memories flutter like spooked chickadees,” Alëna lyrically muses, acknowledging that any work of recollection, especially a creative one, is subjective. Like a Drop of Ink in a Downpour is more ambitious than the average memoir. It’s informed by Galina’s and her parents’ lessons on the value of art and culture and enriched by Alëna’s beautifully constructed images and Galina’s poetry. Yet their tale always feels honest both in its broad strokes and finer details, particularly when they share events that are personally unflattering. In the most shocking example, Galina refuses to accept the seriousness of her legal plight, failing to heed warnings from friends to flee the country immediately, and even when her and Alëna’s visas are taken away, she makes no provision for the guardianship of her daughter in case of conviction. Grappling with this as an adult, Alëna primarily faults their ignorance of their Jewish faith for their catastrophe: without this sense of belonging, they have no capacity to imagine the scale of suffering that they too would be required to overcome, as their forebears did.

Ironically, Felix discourages his daughter from following the artistic path that meant so much to him, just as he carefully distances her from their Jewish faith. His motivation is to protect her from a life of conflict against the state. Art nonetheless becomes her life’s mission. By bringing Felix’s paintings out of the Soviet Union, the Lemberskys have preserved his legacy as an important Soviet Jewish artist, cataloging his works, running an extensive website, organizing exhibitions, and encouraging scholarly research into their archives. Reminiscing about her own painting lessons at university, Alëna muses on art “as a view into a hidden dimension, the revelation, the truth that can’t be told in any other way.” How fortunate then that Yelena and Galina have revealed their own truth, not with the brushwork of Felix, but with words equal to his artistry.

¤

LARB Contributor

Herb Randall’s first short story, “Pictures of Galina,” was published in Apofenie. His writing has also been featured at Punctured Lines, On the Seawall, and STAT®REC. He lives in northern New Hampshire.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Where Coca-Cola Is Synonymous with Freedom: On Margarita Gokun Silver’s “I Named My Dog Pushkin (And Other Immigrant Tales)”

Kate Tsurkan journeys through Margarita Gokun Silver’s “I Named My Dog Pushkin (And Other Immigrant Tales): Notes from a Soviet Girl on Becoming an...

More Than “Tra-La-La”: On Vernon Duke, Igor Stravinsky, and Russian Musical Émigrés

Harlow Robinson turns his ear to “Taking a Chance on Love” by George Harwood Phillips and “In Stravinsky’s Orbit” by Klára Móricz.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!