Things Are Never as Dark as They Seem: A Conversation with Pico Iyer

Pooja Pande interviews Pico Iyer about his new book “The Half Known Life: In Search of Paradise.”

By Pooja PandeMarch 19, 2023

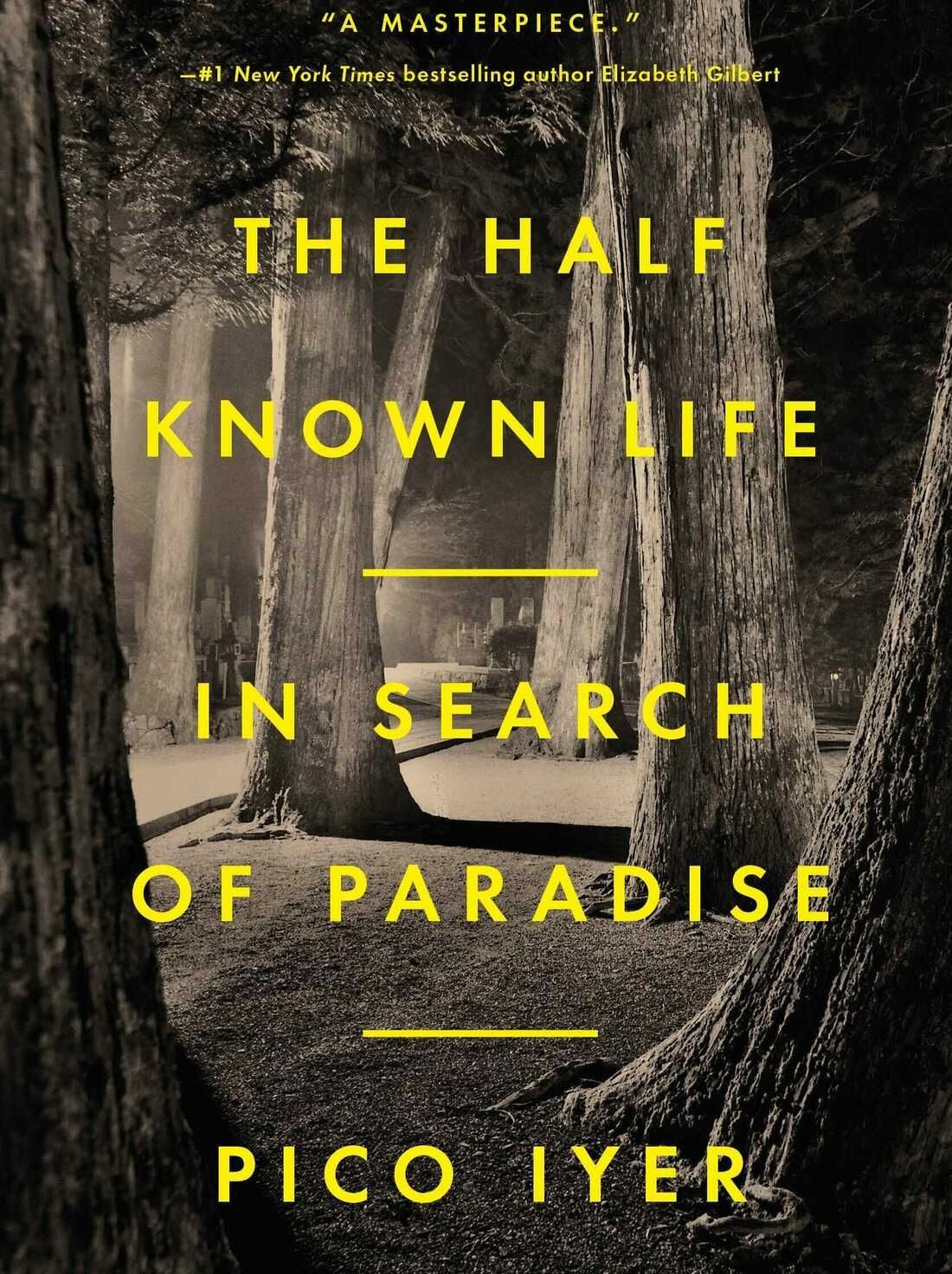

The Half Known Life: In Search of Paradise by Pico Iyer. Riverhead Books. 240 pages.

INTERVIEWING PICO IYER is like reading Pico Iyer. Even as he takes you around the world, he remains a most faithful companion to the spirit of that ultimate journey into uncharted territories—our inner selves. Marrying seeming contradictions such as doubt and hope, reverence and mischief, he remains true to a sense of wonder and a willingness to receive.

Iyer’s latest book, The Half Known Life: In Search of Paradise (2023), is a philosophical travelogue that presents a trippy ride through the frenetic streets of Jerusalem, the stark terrains of Ladakh, the otherworldly landscapes of the Australian outback, the bustling ghats of Varanasi, and the tragically beatific lakes of Kashmir. Informed by the pandemic, laced with the power of uncertainty that leans towards gratitude, The Half Known Life is a vigorous quest for the paradise within—a timely celebration of sustenance.

In this interview, Iyer speaks about the “Entertainment Universe” we all live in today, “the great crown prince of doubt, Herman Melville,” making music with his words, and a feminist hope we both share. Plus, there’s a secret “recipe for instant joy” that puts Van Morrison front and center.

¤

POOJA PANDE: In our stories, myths, and fables, as in real life, reckonings with paradise often feature women in prominent roles. The women of The Half Known Life come across as wisdom bearers, in a way, in a world of “wise men.” I feel this all the times when your wife Hiroko makes an appearance, when the Iranian women chat with you, when Emily Dickinson’s poems surface, or in chance encounters with the likes of Etty Hillesum. Was this a deliberate writing decision?

PICO IYER: It wasn’t deliberate, but I think what you discern is definitely true. More and more people seem to have noticed that women leaders are the ones least inclined to think in terms of divisions, much as women writers are the ones who seem most concerned with the places where we touch or connect. Of course, that’s a vast generalization, but at a time when the world seems more bitterly divided than ever, both locally and globally, I was turning in this book towards anyone with the humanity to see past the texts and ideologies that tear us up. So often it’s women who are less inclined to think of us versus them, and more to focus on just us.

As it happens, I originally planned to center much of the book around a celebrated female Sufi saint, Rabia, who ran through the streets of Basra holding a burning torch and a bucket of water. Her aim, she said, was to extinguish all hopes for heaven and to burn all fears of hell. And in my next book, a companion piece to this one, about a community of Benedictine monks in California with whom I’ve been regularly staying for 31 years, I do deliberately write about the women who in many ways sustain these men and keep the monastery going. One woman there, in her nineties, seems as wise as anyone, and one of the priors there is rightly pleased that his confessor is a married woman!

In what ways is the “half known” different from the “unknown” to you? To me, there seems to be a promise of possibilities in the former and the darkness of a certain uncertainty in the latter.

That’s beautifully said. I think all of us glimpse possibilities in life—when we’re in love, when we’re in sacred spaces or surrounded by scenes of humbling natural beauty, when we’re suddenly inspired. We sense something more than we can begin to explain. It’s as if we have intimations of something better, but then forget them, or get caught up in the chaos and complications of the world again.

Wise people in every tradition say that we never discover truth so much as recollect it: what we need is inside us all along, so long as we wake up to it. Uncertainty is a fact of life, as the pandemic dramatically brought home to every one of us. But I agree that the half-known points in at least two directions. On the one hand, it reminds us to be humble: in the Age of Information, we’re not as knowing or as much on top of things as we like to pretend. On the other hand, it asks us to be hopeful: things are never so dark, or so changeless and absolute, as they seem.

One thing that life has taught me so far is that I never know what’s coming and I don’t really have a clue. Which is cause, in my case, for gratitude more than apprehension.

Connected with the previous question, I also find that the overarching tones of your writing are steeped in affirmation and joy—I have always felt (and loved) this about your books. Is this something you are mindful of as a writer? Something that informs your approach and choices?

Thank you, thank you! How funny that I more or less just expressed this before knowing that you were about to mention it. I do tend to be an optimistic person, if only because I think we have a choice. And I would rather rejoice in what I have—in my case, relatively good health, loved ones nearby, sunshine pouring through my window as I write this—than fret about what I don’t have. I do feel that despair is something of a dead end, and one that can so easily become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

For me, the pandemic really underlined this. Every day when I woke up, there was lots to mourn: my revenue was down to almost zero; I couldn’t travel and I had to cancel all my plans; I was living with my 89-year-old mother, who was nearing the final days of her life. Yet, none of that effaced the fact that the mountains behind my mother’s house were flooded with golden light. The fact that I couldn’t travel meant that I could write as never before—continuously and without distraction. My revenue was down to zero, true, but spending all day every day with my wife and mother felt as rich a life as I could ever conceive.

Of course, we all had to grieve the tragedy that was claiming so many lives and destroying every economy, large and small. But given so much external suffering, as the Dalai Lama pointed out, it didn’t seem helpful to compound that by creating even more suffering, internally, through anxiety or rage. Seeing the many things I—like so many—had to be grateful for gave me the strength to cope with numberless challenges (the death of my mother, for example) and made me hope that my confidence might be what those around me would most appreciate and benefit from.

Given how widely read and well-travelled you are, I wonder: where and how do your readings and actual lived experiences blur? Let’s take Australia’s venomous serpents for example. Is this something you knew already, or did it emerge as you began to write about the outback? What is, according to you, the role of what we commonly call “trivia” in a good travel-writing book, and how does research speak to memory in your case?

What a wonderful question! Nobody has ever asked me this before. Most of the tiny details you see in the book came in the process of writing, and were slipped in to amplify some point or intuition. It’s my reading that draws me to certain places and makes me know that Ladakh or Jerusalem or Iran or Varanasi is going to help me address some essential question or think through some challenge that’s haunting me. But it’s my experience that shows me, once I travel across Australia, that it’s the rich, inner red-dust center that really speaks to me and seems unique (even as the cities give me more of what I might find elsewhere).

I do work hard to keep trivia out, more and more. In my early books, I worked almost entirely from notes, based on both reading and the research I’d done when visiting a foreign place. Now, I generally keep my notes on the far side of the room while writing so I can call on those deeper prompts known as “memory” and “imagination” and “feeling.” A part of me is proud that in a book that begins in Iran, I don’t mention once what is probably the richest and most ravishing site in the country, Isfahan, which dizzied me with its beauty. And in a book that circles ideas of paradise, I don’t include one of the countries I know best, Cuba, which for 35 years has been haunting me with its braided images of utopia and dystopia.

In other words, this is a book where I worked for years to take out almost everything—though certainly to add a few details that wonderfully surfaced as I was writing.

What does a “nonaffiliated soul” seek in his travels—especially travels that, to affiliated souls, are pilgrimages?

Such a good question, again. I use the term “nonaffiliated” of myself—in Jerusalem—to stress that the beauty of such a position is that one can be moved by every tradition. One is not cutting the world up into those people one agrees with and those one opposes. If affiliation brings aversion—and if a commitment to one tradition means a deafness or blindness to every other—then I’m glad not to be closing my eyes and ears.

When I was in Jerusalem, I gained so much from walking out in the predawn dark to see and join the black-hatted Jews in their worship at the Western Wall. Every day I would return to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and stay for long hours in a chapel there, sometimes so moved by its ragged emptiness that I was close to tears. And I was very keen to see the great Islamic sites. They were blocked to nonbelievers at the times when I was visiting, but I tried to make amends by spending a lot of time in Shia holy places in Damascus and Iran, while also visiting Beirut and Yemen and Oman and many other Islamic cultures.

Of course, there is a danger in nonaffiliation: one has to believe in something, and one has to take a stand. If one doesn’t have a single tradition to be part of, one must be sure one is deeply rooted in some kind of commitment and conviction. But at a time when the world and its individual countries are more and more cut up by sectarian conflict, I’m glad if I can learn from the Dalai Lama and the Catholic Thomas Merton and the poems of Hafez—and Emily Dickinson and the great crown prince of doubt, Herman Melville.

I loved how dates and times—the record of history, so to speak—are akin to clues in The Half Known Life, and not definitive milestones like “Kashmir, 2000,” or some such. We read about an American president’s first visit to Jerusalem, for instance, while His Holiness the Dalai Lama plays an eternal timekeeper of sorts (in a jolly maroon robe, of course), the young Chapri spells out a history of Kashmir, and the timelessness of spaces like Varanasi seem to mock our attempts at neatly marking historical events with its drama of mortality. Could you please unpack this approach?

This is a perfect observation, and only one other person—another keen reader from India, of course—has registered this fact.

Nearly all my writing is untopical insofar as I am trying to catch something in my subject—whether it’s a country or, say, His Holiness the Dalai Lama—that stands outside of time. We have many brilliant journalists and reporters who can tell us what is happening in Kashmir right now—and maybe even tomorrow—and who can give us every detail of, say, the conflict in Sri Lanka or the current protests in Iran. They know much more and are far closer to the ground than I could ever be.

But these days, I worry that we’re ever more hostage to the moment. We’re so caught up in what happened an hour ago—brought to us by CNN or social media—that we lose all sense of what happened last year, or of the larger picture beyond the tiny screen. So I try more and more to describe the character of a place—and the enduring questions that it throws up—in ways that will not, I hope, become out-of-date tomorrow.

Perhaps a new leader will come to power in North Korea next year. I don’t think that will change, at least for some years, the nature of that place as I describe it. The convulsions in Iran right now speak for some abiding pattern and theme that I witnessed many years ago, and expect to see several years from now. And, as you say, it’s in the nature of a Varanasi or a Jerusalem—as of a Dalai Lama, perhaps—to try to stand outside the tumult of change a little, and to speak to something more ageless in us, what the German mystic Meister Eckhart called the “place in the soul where [we’ve] never been wounded.”

Funnily enough, in early drafts of this book I did have lots of dates, and even, at the bottom of each chapter, would write, “Sri Lanka, 2009,” or “Kashmir, 2013.” But my brilliant new editor wisely reminded me that, really, I was writing about eternal questions, and offering parables more than political reports. So even where I now describe “a new US president” visiting Jerusalem, as you point out, I only once name the president.

To do so, my editor rightly pointed out, would be somehow to narrow the scope of the inquiry and distract. It’s not, after all, a piece about Bush or Obama; it’s an essay on how much we can believe in a world of constant conflict.

You have an incredible gift for transitioning from the absurd, the banal, to the sacred and profound—again, something I have always been drawn to in your books. Even echoes of Paradise Lost shapeshift in this (for lack of a better word) technique. And I feel like more than a “technique,” this is how Pico chooses to meet life, particularly in his travels. Would this be a fair inference?

In this book, I wanted more of the sacred and the deep than usual, and less of the absurd and the banal because I feel that depth and perspective are what we’re most craving. We’re longing for liberation from the clatter and confusion of the moment. We’re all doing a hundred things every second and being bombarded by updates and beeps and news. What we really hunger for is respite and something that will take us not just out of the chaos but into some calmer, quieter place from which we can remember what we care about and what really matters.

When I began writing, I included much more that was zany or just amusing because the world seemed less distracted then, and we weren’t living in an Entertainment Universe. Now that we are, and we’re flooded with more data than we can ever make sense of, I try to keep out data so that the reader is carried from a jam-packed street in which all the cars are honking their horns to, you could say, a quiet space halfway up a mountain.

So your inference is a fair one: these days—and throughout the pandemic—I worked hard not to spend time on the news and instead devoted my time and energy to what really sustained and enriched me. Every morning when I woke up, I felt I had a choice between turning on the TV or my emails or social media and feeling cut up, jangled, and hopeless—or simply looking outside and taking a walk, and feeling opened up and gloriously filled with a fresh sense of possibility.

I hope this isn’t a mark of irresponsibility, because in nonpandemic times I try hard to go to war zones and to the poorest countries on earth, and I work to give a human face and voice to Yemen, Haiti, Ethiopia, Cambodia, North Korea. But I sense a universal need for wise voices who can offer clarity and guidance, which is why this book is full of the Dalai Lama, Emily Dickinson, Thomas Merton, and all the others.

During the pandemic, Milton was someone who kept me very good company—along with Melville and Proust and Hilary Mantel. I hadn’t read Paradise Lost since my twenties, and it was wonderful to be reminded how the archangel who ushers Adam out of Eden urges him to find a “paradise within thee, happier far.”

I’m interested to hear more about the personal baggage of caste and religion that was looming through the Varanasi pages, which are perhaps unresolved in many an Indian identity—it certainly is the case for me—and how these tend to weigh heavily in a space that seems to demand such markers as very definite signifiers of one’s self.

Again, for better and worse, I came to Varanasi as a nonaffiliated pilgrim. I am 100 percent Hindu by birth, but my parents were both theosophists, which meant that they both were conversant with and respectful of most of the world’s great religions. Indeed, my father was a philosopher and my mother was a professor of comparative religions who would teach with such sympathy the beliefs of Islam, Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism, and Hinduism that her students wouldn’t know which was closest to her heart.

I am keenly aware that most people in India could write a much better informed, more personally involved, and more intimate account of Varanasi than I ever could. I fear I come to it much as I do to Jerusalem, as someone not familiar with all the subtleties and meanings that a true devotee would find there.

At the same time, Varanasi is a strikingly charismatic place that has always drawn every kind of religious teacher and believer (as one sees in Japanese Christian writer Shūsaku Endō’s novel Deep River). And only six miles away from the city, I got to hear the Dalai Lama speak in Sarnath, which in that week looked like a Tibetan encampment. And I met in Varanasi a German Sufi I’d last seen in Berlin, and a heroic woman psychiatrist working in war zones who described all life as a pilgrimage. Plus, maybe most important of all, an old school friend of my father’s, who opened all kinds of beautiful doors to the history of my family and my lineage that otherwise I might never have known.

The auditory nature of your writing is even more powerful in The Half Known Life. I was compelled to read a lot of it out loud. Are these the kinds of books you enjoy reading as well?

You don’t know this, but this was the first major book of mine for which I was invited to record the audiobook. And that was a great experience. I work hard on the cadences of my sentences and often think I’m trying to make music more than an argument or even a story. Yet of course this is somewhat quixotic because the way I read my sentences in my head—given my accent and particular rhythm—will seldom match that of a reader. I am trying to fashion a piano melody that will be heard by a reader as if it were refracted through a hundred tunnels.

It was wonderful at last to get the chance to read the book aloud and to present the text with the emphases and melodies that I had in mind while writing it. And it was a tremendous experience to spend those 10 hours reading the book aloud because it helped me notice inadvertent repetitions and even mistakes I’d never caught before. Even though the book was almost finished at that point, I started sending my poor editor all kinds of belated corrections, because actually vocalizing the words helped me see where I’d gone wrong or failed to register some dissonance.

How do hope and history rhyme in your playlist?

This sounds like an invitation to mention Van Morrison, who sings out of the opening of the book. I was so moved—and it came to seem so important—to find the house where he was born, in a very featureless, almost bleak area of lookalike, tiny, red-brick houses in industrial East Belfast. The man who grew up there, surrounded by conflict, with no advantages, somehow gave us some of our most soaring evocations of paradise and golden possibility, following in the tradition of William Blake and William Wordsworth.

You have been asking me often about joy, and my recipe for instant joy is listening to Van Morrison: both for the unquenchable vitality of his voice, even in his mid-seventies, and for the radiant landscapes he paints in his words, as well as his gasps and his silences.

The inspiring words of his neighbor in Belfast, Seamus Heaney, about how, once in a lifetime, hope and history rhyme first came to me through another great Irish singer and dweller on possibility, Bono, and his work with U2. Given that Ireland has suffered as much as anywhere in the West over the course of my lifetime, it’s wonderful that these singers can celebrate hope, for all the scars and memories that history leaves behind.

¤

LARB Contributor

Pooja Pande is a writer and TED speaker whose books include Red Lipstick: The Men in My Life (2016), a literary-styled memoir of celebrity Indian transgender rights activist Laxmi, and Momspeak: The Funny, Bittersweet Story of Motherhood in India (2020), a feminist exploration of the institution and experience of motherhood. Her day job is in media, where she is currently the co-CEO of Chambal Media, home to Khabar Lahariya, India’s singular news platform featuring reports by rural women from marginalized communities.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Strangers No More

Jason Christian finds “The Kindness of Strangers,” the new travelogue from Tom Lutz.

A Life in Airplane Mode: Pico Iyer’s “Autumn Light”

Madhav Khosla reviews an exquisite memoir of transience and loss.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!