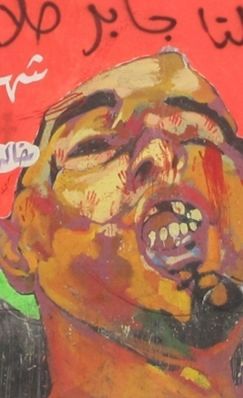

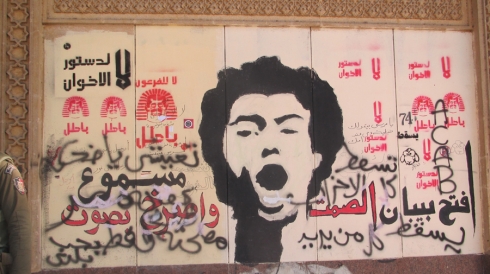

THE FACE OF 19-year-old Khaled Said, the catalyst for Egypt’s January 25 uprising, is stenciled all over Egypt. But if you walked down Mohamed Mahmoud Street, which ends in Tahrir Square, you would see his mutilated face after he was beaten to death by cop thugs. Beside his face, the artist Ammar Abo Bakr also depicts the disfigured images of other victims, including the young Shenouda Noshi Atteya, one of the 28 killed in the Maspero Massacre of October 2011, in which peaceful protesters, mostly Coptic Christians, were killed by the army.

The faces depict the fallen of Egypt’s revolution, a revolution that continues two years after Hosni Mubarak’s departure in February 2011. Mubarak’s regime was first replaced by the regime of the armed forces, and then by the current, increasingly repressive Muslim Brotherhood. These are the faces of the moment.

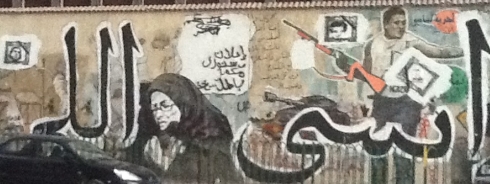

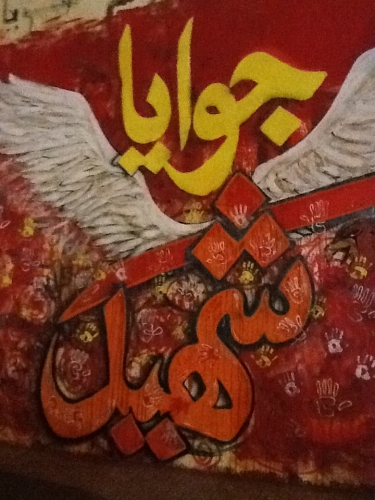

That the fallen are called “martyrs” — and that they are Muslim, Christian, secular — speaks to an idea that transcends religious boundaries and celebrates the loftiness of the revolution’s goals: bread, freedom, and social justice. In early 2013, Egypt’s graffiti is decidedly realistic, bloody, and brutal, reflecting the reality of a continuing struggle that has claimed, among other things, the lives of more than 2,000 people: Alaa Awad’s murals draw inspiration from pharaonic murals in his native Luxor; Ammar Abo Bakr’s sad-eyed mothers of martyrs hold the images of their departed to their breast; Omar Fahmy replicates Mubarak’s face on the bodies of Central Security Forces.

Photo by: Iman Hamam / Artist: Ammar Abo Bakr

Photo by: Jonah Moos / Artist: Alaa Awad

Photo by: Andy Young / Artist: Ammar Abo Bakr

Photo by: Mona Abaza / Artist: Omar Fahmy

Could you peel the paint back to the layers beneath, you’d see a palimpsest of the country’s moods and reactions to the various guises of power. Graffiti is the expression of the revolution, its periodic whitewashing an attempt to erase memory or assign blame, its persistence a symbol of stubborn resistance.

If the walls are the book and graffiti the revolution’s message, poetry is a visible part of that telling. “There is a martyr inside me” reads one image, the “me” being the writer/painter, or perhaps the reader. Lines from Tunisia’s Abu al-Qasim al-Shabbi’s poem “The Will to Live” are often scrawled here: “When the people demand freedom / Destiny must surely respond.” As translator Elliott Colla points out in “The Poetry of Revolt,” his article on Jadaliyya responding to the 2011 revolution: “The poetry of the streets is another form of writing, of redrafting the script of history in the here and now — with no assurances of victory, and everything in the balance.”

As an American poet, I often lament the lack of importance given to my vocation. Poetry is simply not part of the nation’s discourse. Yet, when it is hard to find meaning in life’s difficult moments, people sometimes turn to it, thumbing through a dusty anthology or asking for advice on a poem to read at a loved one’s funeral, for example, or sharing a poem that can speak to a national tragedy. Standing with my family in Tahrir Square — which, it must be said, is actually a circle — where everything is at stake, I must admit to feeling a charge in observing that poetry is part of the dialogue.

¤

The square is a dizzying display of simultaneity: pitched tents (at least one with a small satellite dish bolted to the ground beside it); men selling sweet potatoes; loudspeakers with the messages of the martyrs’ fathers; white flags with the faces of martyrs such as 16-year-old Jika, recently killed, and the beloved sheikh Emad Effat, killed in late December 2011, which wave through and over the crowd like sails; a French school, recently the site of battles, now singed and rubble-filled; field hospitals, which are little more than roped-off street corners; in the distance, the pop of tear gas canisters; newscasters perched on trucks above the crowd; couples having picnics; a small stand selling organ meats; a man walking around with a medical mask and a tray of bread balanced on his head; rainbow Mohawk wigs; face painters; people shucking and roasting corn; tea in plastic cups; green laser lights; a makeshift museum with cartoons, newspaper articles, and images of the dead; the word kafiya, which means “enough,” in Christmas lights.

Nearby, coffee shops, shoe shops, and restaurants are open as usual — bustling, even. As a man poured our coffee, a wave of chanting could be heard down the alley, out of sight. “If you decide to join,” he said, “leave the cups.”

Chants rise up in and around the square like waves: “Aish, Horeya, Adela Egtamaaiyah,” or “Bread, Freedom, and Social Justice,” the revolution’s original slogan, or more recently, and less poetically in English translation: “Bread, Freedom, and Down with the Constitutional Assembly.”

Most of the chants, with the lyricism of short poems, lose a great deal of their music in translation. Take the most common chant, heard across the Arab uprisings: “i-SHAAB / yu-REED / is-QAAT / il-ni-ZAAM,” which translates as “The people want the fall of the regime.” There is the initial problem of “the people” being a singular noun in Arabic. But beyond that, there are more subtle nuances at work. “The register of this couplet straddles colloquial Egyptian and standard media Arabic — and it is thus readily understandable to the massive Arab audiences who are watching and listening,” says Colla. He also points out that, while the couplet is not rhymed, its regular metrical and stress pattern lends itself to a unified cadence. While the rhythm may be lost, many lines do come through in their poetic essence, as in this chant: “Have a Party. Bring a Dancer. In my chest there is still space for a bullet.”

¤

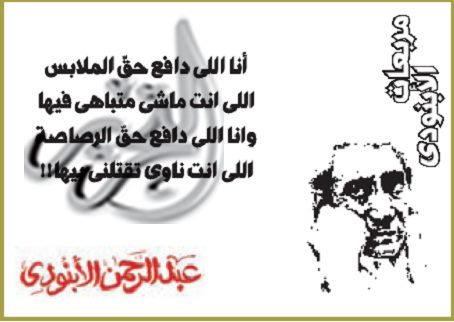

As I walk around Tahrir Square I hear, echoing from a boom box and from the lips of dancing, clapping men, “I swear by its sky and its land / I swear by its gates and its roads […] I swear: no one will block the sun / or hide it as long as I breathe.” The words are those of poet Abdel Rahman el-Abnudi whose poem “I Swear,” a poem integral to Egypt’s 1952 Revolution, was put to music decades ago but is still played today.

El-Abnudi’s recent poems are also featured daily in the newspaper El Tahrir — imagine! a poem on the front page of a major newspaper. Here is a recent one:

I am the one paying for the clothes

you strut around in

I am the one paying for the bullet

with which you intend to kill me

An often-quoted single line of el-Abnudi’s, written decades ago, is also, depressingly, relevant: “Your hangman is a lawyer, and your protector is a thief.”

From El Tahrir newspaper

In another pocket of the square resound the words of the beloved Salah Jahin, a poet, cartoonist, and playwright widely considered the father of shi’r al-ammiya, or colloquial Arabic poetry. He was the voice of the 1952 Revolution, but remains relevant, quoted by everyday people, including the illiterate:

speak up speak up speak up

speaking is beautiful and necessary

in the beginning was the word of God

it created life and people have learned from it

speak up

the word is a hand the word is a foot the word is a door

the word is a bright star in the fog

the word is an iron bridge over the ocean of fear

even jinns, my dears, cannot demolish it

speak up

And then there are the words of Ahmed Fouad Negm, which are everywhere — chants, songs, graffiti, rallying cry:

The brave man is brave

The coward a coward

Come down with the brave

Come down to the square

Negm, an irreverent poet in his 80s, has been one of Egypt’s most prominent voices of resistance for decades. In the 1980s, if you were caught with a tape of his poems, which were recorded in song by the blind Sheikh Imam, you could be sentenced to jail for six months. Negm is no stranger to imprisonment. One of 17 children, he was raised in an orphanage and first went to prison for petty crime. He learned to read in jail, cutting his teeth on translations of the Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet and Pablo Neruda. Later, it was for his outspoken resistance through poetry. His 11-year sentence during Anwar Sadat’s rule propelled him to fame across the Middle East.

His daughter, Nawara Negm, has been one of the leaders of the revolution since its beginning. In early 2012, she was beaten by 25 pro-army protesters outside of her workplace, the men insulting her, in part, because of her father’s work. Nawara shares her father’s defiance, calling her attackers “so-called men” in an interview, and saying, “I have to say their beating was harmless. I call for our army to send snipers next time.”

While Negm’s poems are no longer banned (at least for now), he is no favorite of the current powers that be. Recently, after calling into a political talk show, he was taken to court by a little-known Salafi group, the New Muslims, for what they perceived as insulting religion. But that has not stopped his words from resounding in the square through chants and music, and from the man himself, who often takes to the stage to inspire the protesters. He can often be found at Merit Publishing House, a small press off the square that is a hub for intellectuals and activists.

Merit is a usual stop for us when we spend an evening downtown. After joining a Friday protest against Morsi’s claim to extrajudicial power last November, we stopped by to find Negm holding court, jovial and fiery, wagging his finger as he discussed what was happening under Morsi. It was inspiring to have the chance to meet him and to literally sit at his feet in that crowded room.

Here is one of his most quoted poems:

Poem of Prohibitions

banned from travel

banned from singing

banned from talking

banned from longing

banned from discomfort

banned from smiling

and every day of my love for you

the prohibition increases

and every day I love you

more than the day beforemy love you are a ship

imprisoned and longing

an informer in each knot

a soldier in each port

prohibiting me from jealousy

from flying to you

from embracing you

or sleeping on your lap

from your heart of spring

where I return to infancy

suffering from weaningmy love you are a city

dressed up and sad

in each alley a sorrow

in each palace lightsbanned from waking up

with your love or falling asleep with it

banned from discussions

banned from silenceand every day of my love for you

the prohibition increases

and every day I love you

more than the day before

Ahmed Fouad Negm and Andy Young

The disheveled and lively front room displays the publishing house’s titles, an eclectic collection of some of the best contemporary Egyptian literature being written. In the next room, writers, friends, and activists line the wall, taking turns making tea, talking, and debating the latest issues. Over the course of the last two years, the place has also been a refuge for tired or injured protesters who come here to rest. The publisher, Mohamed Hashem, has come under fire under every regime for aiding protesters (sometimes handing out gas masks and helmets) and fomenting resistance through his support of young writers.

Besides these bigger names on the scene, there are countless other poet-activists whose poems feed into the political discourse and the immediacy of the streets. The words of younger poets are also chanted, quoted, spoken, and distributed on fliers, such as this one by Mostafa Haasan:

we are standing until the asphalt speaks until tear gas understands the difference

between this tear and the tears of the poor

until the flags replace the shotguns in the square

until the gunpowder becomes ink for writing

until flowers grow in the soldier’s hands in the square

we are standing until the birds eat the flesh of our shoulders

we are standing without any deal with time

we are standing until the asphalt speaks

¤

A ripple of people is parting the crowd. Celebrities are often down here: movie actors, singers, politicians, various heroes of the revolution. Cameras snap, an arm-ringed line of people encircles the figure: a short woman in a black and white head scarf moving slowly and determinedly. Layla Marzouk, the mother of Khaled Said. Tahrir holds a special place of honor for the mother of a martyr. In the States, I have only seen this kind of reverence and attention bestowed on rock or movie stars.

We follow them like groupies. I wrote a poem about Said’s mother after seeing a clip of her the night the Mubarak regime fell. She was smiling quietly, fireworks visible over the balcony through the open door behind her, as she held a pillow with her dead son’s face stitched on it. Now here she is, slowly making her way through the noise and crowds in support of the ongoing struggle. She ends up at the coffee shop where we usually go.

I kneel beside her where she sits, and Khaled, my husband, brings her a copy of my book, tells her it has a poem about her in it. She takes it, takes my hand, and calls me her daughter. I kiss her hand. She says I am a light on the square. And I am beyond humbled. Leaving, I can’t help but think how I’ve left her with a small book in her hand that contains a small poem about her holding an image of her dead son. She is kind and gracious about the gift. But I am sure she would rather have her son.

Khaled Said's mother and Andy Young

It is strange to be here in the middle of it, this place that has occupied my mind for so long. How is it different, I wonder, to witness this in person than to see it on a screen on the other side of the world? It is, ultimately, not my struggle. I am an outsider, even if I am welcome. I think about the idea of poetry as “witness,” which seems to be the way much contemporary American poetry that deals with “politics” is categorized.

Am I more or less of a witness being in front of the actual woman I wrote the poem about than when I was watching her on a screen across the world? Am I more or less helpless to repair what has been broken? Thinking of her son, represented nearby in both his living and dead forms, I wonder if, here, we are not all witnesses, in one way or another, to the martyrs? We are the ones left to speak.

Of course, the place where people have come to have their voices heard in Egypt has traditionally been Tahrir. “Tahrir” itself means “freedom,” and the spot is also the subject of a famous poem by Amal Donqol that reflects on a 1972 student protest dispersed by force. The poem, “A Song for a Stone Cake,” is now commemorated with a plaque on Mohamed Mahmoud Street. The “stone cake” refers to the plinth, no longer present in the square, around which the protesters gathered. Here is an excerpt:

the clock struck five

the soldiers came: a circle of shields and war helmets

slowly, slowly drawing closer

from every direction

and the singers in the stone cake clenched

and released

like a heartbeat

their throats aflame

to warm them against the cold and the biting darkness

they raised their anthems in the face of the approaching guards

and linked their young, desperate hands

as a shield against bullets

bullets

bullets

they were singing “we die for you Egypt”

“we die …”

The poem helps to put the current revolution, and its epicenter, in dialogue with past struggles. Young people gathering in the square did not begin in 2011. Nor, as seen in the poem, is the brutal repression of such demonstrations new. The phrase “raise their anthems” referenced in the poem feels contemporary, as revolutionaries have embraced symbols of their country, such as the flag and national anthem, in an attempt toward ownership.

¤

The scene downtown changes week to week, sometimes day to day. One night, it was a little hectic. The field hospital on Talaat Harb Street, which also ends at the square, hardly resembled a hospital. It had some doctors — that was about it. It was really a street corner roped off with a single thin rope, some mats on the floor, and, that night, a constant supply of prone young men who needed urgent attention. My husband and I follow Tahrir Supplies on Twitter and had brought some supplies they said they needed. Some of those they were attending, a doctor told us, had been hit by rubber bullets. Most of them, though, had succumbed to the gas. One foamed at the mouth, his body convulsing. This, the doctors say, is a typical reaction to exposure to this gas, whatever it is.

The gas, it is said, is not “normal.” Last year, as now, people claimed it was a nerve gas, some illegal neurotoxin imported from the US. The videos from that time show young men with blackened fingers pointing to the letters “USA” on the canisters. Protesters reported that the compound organophosphate had been isolated as one of the main ingredients. It’s a nasty piece of work causing convulsions, unconsciousness, even death. During that time, I wrote a poem called “Organophosphate” after following news and live feeds showing these streets, these effects. In the poem, I struggle to understand that what I saw was real, was live, was on the actual streets where my friends lived. Now that it was in front of me, now that I saw a man, foaming, his legs kicking wildly, I found that I had no words. Such are the limits of poetry.

But what is at stake is enormous. Just look at some of the other poets of the Arab Spring: Qatari poet Muhammad al-Ajami, sentenced to life in prison (the sentence was recently commuted to 15 years) for insulting the emir, or Syrian poet Ibrahim al-Kashoush (who wrote a poem that begins “Freedom is at the door / Bashar leave),” found dead in the Assi River, his body having been tortured, his throat, it is chillingly said, “removed.” Egyptian poet Mohamed Kheir was on his way to Tahrir Square when he was arrested. The young Bahraini poet Ayat Kormuzi, who criticized King Hamad Khalifah in a long poem that starts “We don't want to live in a castle, we don’t aspire to the presidency / we kill humiliation and assassinate misery” was also jailed. Ayat Kormuzi, from Bahrain, was also imprisoned for a poem criticizing King Hamad Khalifah which begins: “We don’t want to live in a castle, we don’t aspire to the presidency / we kill humiliation and assassinate misery.” That poets risk so much to speak says everything about its importance.

With Egypt’s new constitution, fears about freedom of expression are rife. Doaa el-Adl, a female cartoonist, faces charges of blasphemy for her recent work, and Dr. Bassem Youssef, Egypt’s much-loved answer to Jon Stewart, is under investigation for insulting the presidency.

So many of my American friends say they cannot “watch the news” because it is (some variation of) too overwhelming or “so depressing.” But ignoring the news is a privilege, only nonessential if it does not have immediate impact. I wonder if there is a relationship between that privilege and the expendability of poetry.

A poetry that resonates in the street, that matters to everyday people, has always been an ideal to me. I think of Neruda’s poem being echoed back by a group of workers when he found he did not have the requested poem with him at a reading. Hearing poems resounding in the street, in chant, in song, in paint, rivals the inspiration I feel from the willingness of Egyptians to continue their struggle despite its being exhausting, violent, and, seemingly, endless.

“[Poetry] is now cultivated on the street, in the square and the alleys, in meeting rooms both real and on-line,” writes Mazen Maarouf in an opinion piece on AlJazeera.com. Maarouf is a Palestinian poet raised in Lebanon who now lives in Iceland, having been forced into a double exile because of his words criticizing Syria. “The protesters are now […] the medium of the poem. In the street nobody is silent, nobody is whispering the poem. They chant it defiantly.”

In 2013, the chanting, and the struggle, continues. Even the presidential palace, surrounded by ornate calligraphy, became a canvas in late 2012: President Morsi was depicted as a giant, hideous octopus, as a clown, as a pharaoh.

Photo by: Iman Hamam

unknown artist, photo by: Andy Young

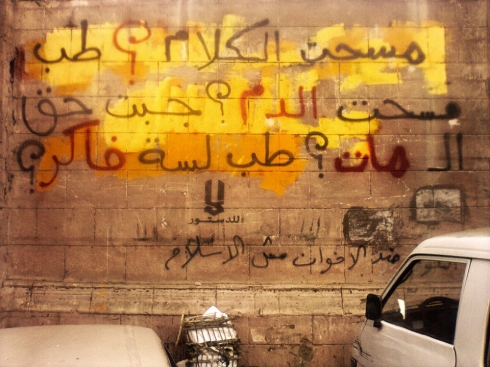

When text does appear now, the word blood often does, too. Here, the word dem, or “blood,” which is the only word in Arabic that does not share a root with another word, is written in what appears to be actual blood.

And here, where the words read:

“So, you erased the words? Did you also erase the blood?

Did you bring justice to the martyrs? Do you even remember?”

Photo by Andy Young

Presidential Palace / Photo by: Hossam Kewea

¤

The term “the writing on the wall,” it is said, comes from the book of Daniel, when King Belshazzar hosted a banquet and a mysterious hand wrote a message on the wall. The prophet Daniel interpreted it as the foretelling of the imminent demise of the Babylonian kingdom. That night Belshazzar was killed and the capital city sacked.

Whether or not the authorities see the irony of their doom depicted on the president’s palace, the inevitable whitewashing came in late December. The images were erased under a new coat of paint, a sterilized backdrop for the swearing-in of new members of the debated Shura Council.

The process of whitewashing and repainting the walls has been ongoing on Mohamed Mahmoud Street since the revolution’s beginning. Fahmy’s image of the security forces with Mubarak’s face multiplied and superimposed on them reflects on the feeling that Egypt is still living under the old dictator. His work also features a poem commenting on the ongoing attempt, and its ineffectuality, to erase resistance:

Oh regime that is scared of a pen and a brush

you’ve been unfair to the people you crushed

if you were honest

you would not fear paint

the best you can do is fight walls

and claim victory over colors and lines

¤

All Arabic translations by Khaled Hegazzi and the author

LARB Contributor

Andy Young is the author of the chapbook The People is Singular, a collaboration with Alexandrian photographer Salwa Rashad. She is the co-editor of the Arabic/English literary journal Meena Magazine, and her translations, with poet Khaled Hegazzi, were featured in the Norton anthology Language for a New Century: Contemporary Poetry from the Middle East, Asia, and Beyond. She lives in Cairo, where she teaches at the American University in Cairo.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Europe Through the Looking Glass: Nina Martyris on Pallavi Aiyar

An Indian author, having written about China, turns her gaze to Europe.

The Gaza Poetry Roundtable: Part III

Palestinian and Israeli Poets in Conversation

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!