The Wound in the Willows

Rewriting Kenneth Grahame’s classic children’s story.

By Robert MintoMarch 8, 2018

EVERY FAMOUS STORY inspires fan fiction, but Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908) has inspired an unusual number of book-length extensions and reinterpretations. I’ve spent the last few months reading some of those tributes, discovering in the process a darkness just beneath the skin of my favorite children’s book.

Robert de Board’s Counselling for Toads (1998) presents Grahame’s story as a handbook of human pathologies. Jan Needle’s Wild Wood (1981) retells it in a way that reveals its class prejudices. Even books that seek to recreate the gentle beauty and good humor of the original — such as William Horwood’s Tales of the Willows quartet (1993–1999) or Kij Johnson’s The River Bank (2017) — emphasize its flaws, such as the curious absence of major female characters. Returning to The Wind in the Willows in this way was like pressing an unexpected bruise. The pain, I discovered, comes from Grahame’s own life, from his frustrations and fears, his thwarted ambitions and mistakes in love.

In 1920, Grahame’s son — whom he called “Mouse” — died in what seemed to be a suicide. The 19-year old prostrated himself on a railroad track and allowed a train to decapitate him. The tragedy of Mouse was the culmination of an arc begun in Grahame’s own childhood. As a boy, he had longed to attend Oxford, but a skinflint uncle insisted he go to work in the Bank of England instead. Grahame was determined not to inhibit his son’s dreams in turn, and he overcompensated. Though Mouse was not academically inclined, his parents treated him like a boy genius, setting him up for frustration and disillusion. (Similarly, though Mouse was born blind in one eye, his parents refused to acknowledge his disability and pretended it didn’t exist whenever they talked or wrote about him.) Grahame sent Mouse, naturally, to Oxford. At the time of his death, the boy was studying to retake an exam he had already failed multiple times. The tutors’ book for Christ Church college holds the annotation beside his name, “pass or go” — pass the exam or leave the university. He was burdened by the urgent expectations of a parent who saw him as a second chance at life.

Without Mouse, Grahame would never have written The Wind in the Willows. Although he had published a few short pieces prior to his son’s birth, it was not until he began telling him bedtime stories about a bombastic toad that Grahame found his way as a writer. A decade before Mouse died, the bedtime stories had grown into The Wind in the Willows. The book seems eerily to foreshadow Mouse’s fate. Toad, whose character may have been based on Mouse, is obsessed with motor cars and frequently crashes them. This echoes a dangerous childhood game Mouse liked to play: he would lie down on the road so that cars would be forced to stop to avoid running him over — just as, years later, he laid himself down in front of a vehicle that didn’t stop.

Mouse is not the only tragic feature of Grahame’s life reflected in his book. The idyllic setting of the riverbank recalls a brief period of happiness in the author’s childhood, when he lived with his grandmother in an English country estate on the bank of a river. Before those years he lived in Scotland, where his mother died and his alcoholic father proved unable to care for him; after those years he found himself in ugly lodgings, a brutal boarding school, the bank. Grahame once wrote, “I can remember everything I felt then […] from four till about seven. […] After that time, I don’t remember anything particularly.”

The friendships at the heart of The Wind in the Willows reflect yet another secret pain. Grahame was trapped in a loveless marriage, and as an adult he longed for male companionship and seemed to fear and despise women. Some speculate that he was gay. “Homosexual acts” were not decriminalized in England until the 1960s, but for much of his time as a banker Grahame lived during the week in a London house he shared with the artist Walford Robertson, only living with his family in Berkshire on the weekends. Could the emotionally tender all-male friendships in his book, and especially the cohabitation of Mole and Rat, represent his own secret wishes?

¤

No work of Willows fan fiction is stranger than de Board’s Counselling for Toads. Toad falls into depression, and his friends compel him to go to a counselor:

“Now look here, Toad,” [said Badger,] “this can go on no longer. We are all trying to help you, but it seems you won’t (or can’t, thought Mole perceptively) help yourself. There is only one thing left. You must have counselling!”

Most of the book consists of Toad’s weekly meetings with his counselor, a Heron, who helps Toad work through his pathologies by applying the principles of transactional analysis to his relationships with the Badger, the Rat, and the Mole. Transactional analysis claims that we establish childlike, parental, and adult aspects to our personalities early in life. Subsequently, we deal with most situations by cycling between these “ego states” and playing out “scripts” in relation to other people. Toad has been adopting a child state in response to Badger’s parent state, for example, and playing out the script of “pity me!”

I don’t know if de Board was aware of Grahame’s biography, especially his sad relationship with his son, but I couldn’t help wondering what a good counselor might have done for Mouse or Grahame himself. Yet de Board undercuts his case. The widely beloved work of art he uses to convey his message only exists as the cluster of pathologies he tries to clear up, so his message has the unfortunate implication that what is beautiful about the world of the River Bank will be dissolved or annulled if the animals who live there improve their mental health.

The closing chapter of Counselling for Toads shows Toad, Mole, Rat, and Badger meeting for a dinner at which they describe their plans to move away from each other and pursue various private ambitions. Badger is running for political office, Mole is opening a restaurant, Rat is finally going to sea, and Toad is “going into estate management.” It’s all very healthy and forward-looking — and unintentionally depressing.

Perhaps some wounds are too deep to be easily healed without destroying what is good in our lives. The loveliness of Grahame’s portrayal of friendship has been much commented upon. It doesn’t consist merely in chumminess — “messing about in boats,” as the famous line has it — but in sensitivity, making amends, and forgiveness. In the chapter “Dulce Domum,” one of the most tender in The Wind in the Willows, Rat and Mole are making their way home from Badger’s house in the Wild Wood to Rat’s house on the riverbank, when suddenly Mole smells his old hole. He asks if they can stop. Rat doesn’t hear him and presses on:

The Mole subsided forlornly on a tree-stump and tried to control himself, for he felt it surely coming. The sob he had fought with so long refused to be beaten. Up and up, it forced its way to the air, and then another, and another, and others thick and fast; till poor Mole at last gave up the struggle, and cried freely and helplessly and openly, now that he knew it was all over and he had lost what he could hardly be said to have found.

The Rat, astonished and dismayed at the violence of Mole’s paroxysm of grief, did not dare to speak for a while. At last he said, very quietly and sympathetically, “What is it, old fellow? Whatever can be the matter? Tell us your trouble, and let me see what I can do.”

[Mole explains:] “I know it’s a — shabby, dingy little place,” he sobbed forth at last, brokenly: “not like — your cosy quarters — or Toad’s beautiful hall — or Badger’s great house — but it was my own little home — and I was fond of it — and I went away and forgot all about it — and then I smelt it suddenly — on the road, when I called and you wouldn’t listen, Rat — and everything came back to me in a rush — and I wanted it! — O dear, O dear! — and when you wouldn’t turn back, Ratty — and I had to leave it, though I was smelling it all the time — I thought my heart would break. — We might have just gone and had one look at it, Ratty — only one look — it was close by — but you wouldn’t turn back, Ratty, you wouldn’t turn back! O dear, O dear!”

Rat feels terrible about his haste and failure to heed Mole’s desire. He leads Mole back the way they came until they find his little hole. They bustle about, cleaning it up, making it cozy, and Rat exerts himself to speak admiringly of Mole’s possessions and arrangements. At last, after an evening of pleasurable homecoming,

[t]he weary Mole […] was glad to turn in without delay, and soon had his head on his pillow, in great joy and contentment. But ere he closed his eyes he let them wander round his old room, mellow in the glow of the firelight that played or rested on familiar and friendly things […] He was now in just the frame of mind that the tactful Rat had quietly worked to bring about in him.

There is no way for the friendships at the heart of The Wind in the Willows to be as meaningful as they are without the processes of wounding and binding they involve. This is a psychological wisdom Kenneth Grahame grasped, for all his ill-hidden pathologies, and that de Board misses in his fantasy of therapy. “You will always be a close friend, Mole,” says Rat at the end of Counselling for Toads, “but I must move on.” This arid declaration of independence can’t hope to compete with Grahame’s lovely vision of the tenacity of friendship.

¤

Kenneth Grahame was descended from the kings of Scotland, and, by the time of his retirement from the Bank of England, he was also a major cog in a modern capitalist society. His attitudes reflected his class. In The Wind in the Willows, he distinguishes the river-bankers from the stoats and weasels of the Wild Wood, who are, without exception, portrayed as untrustworthy and undeserving. Of course this stark projection of classism onto the geography and demographics of his fantasy has not gone unnoticed. In Return to the Willows (2012), for example, Jacqueline Kelly uses a friendship between a nephew of Toad and a young weasel to question the divide between River Bank and Wild Wood. By far the keenest interrogation of Grahame’s classism, however, was penned by Jan Needle, a journalist and prolific novelist.

Needle’s Wild Wood is not a sequel but a retelling. The events of The Wind in the Willows are conveyed from the perspective of the stoats and weasels who collectively form the antagonists of the original story. In Needle’s version, it is the hardhearted and complacent river-bankers, with their unearned wealth and intolerant attitudes, who form the natural antagonists. The plot to seize Toad Hall while Toad is in prison for reckless driving is reconceived as an abortive revolution by the proletariat of the Wild Wood:

[W]hile the Wood’s been painted as a sinkhole full of scroungers and low-lifes, the ones who started it, the ones who’d still be locked in prison if they weren’t so blessed rich, got off scot-free. Oh, there’s two sides to every story, let me tell you — and our side ain’t even never seen the light of day. […] The River Bank was where the smart set lived. Not all of them were exactly rich, but it was hard for us not to notice that while we all worked our fingers to the bone to keep a roof over our heads and a bite of food in the larder, they did very little that wasn’t directly connected with pleasure and leisure.

Needle’s contribution — one of the best books in the wake of the willows — is a comprehensive assertion of the desirability, in its own right, of lower-class culture and community. The Wind in the Willows opens with the Mole leaving his hole and discovering spring on the River Bank, learning about the pleasures of boating from the Rat, and choosing to come live with him. Wild Wood opens with a rollicking party at the house of a hard-up but generous weasel family. Quickly, however, the problems that afflict the average Wild Wooder overtake the story — poverty, difficulty finding work, insults at the hands of the toffs on the River Bank. By the time the Chief Weasel and his sinister henchman, a revolutionary activist of a stoat, organize the ill-fated takeover of Toad Hall, it’s hard not to find one’s sympathies entirely on the side of the Wild Wooders. Even the language of Needle’s novel — aggressively colloquial and vigorous — seems to represent a different order of values from the aestheticized and occasionally saccharine prose of Grahame.

If the working class receives an insulting caricature in The Wind in the Willows, at least they are given representation of some sort. The same cannot be said for women. There are no women in Grahame’s book. Or, at least, there are no anthropomorphized animal women. We do meet three human women: a jailer’s daughter, who takes pity on the Toad when he is imprisoned and helps him to escape; a washerwoman, who loans the Toad her clothes as a disguise; and a barge-woman, who calls him a “horrid, nasty, crawly Toad” and throws him off her boat. Unlike Toad, Rat, Mole, and Badger, these female characters only exist as one-dimensional representations of a specific feeling — pity or disgust — or as plot functions.

As with Grahame’s classism, his apparent sexism has frequently been addressed by his prolific fans. Usually, however, the form this redress takes is to introduce a love interest for one of the original main characters. Jacqueline Kelly, in Return to the Willows, gives Rat a love interest; William Horwood’s Toad Triumphant (1995) gives Toad one. Horwood only manages to reiterate and intensify the authentically Grahameian note, however, representing Toad’s narrow avoidance of matrimony as a fortuitous escape, and including dialogue like this:

“Perhaps it is enough to say that we along the River Bank have no need of females and have lived happily without them for a large number of years,” said the Rat judiciously as he finally led the way into Toad’s garden. “They are perfectly all right in their own place but perhaps they would feel uncomfortable here.”

Only Kij Johnson, in The River Bank, introduces into Grahame’s mythos women who exist as characters of interest in their own right and not as mere ciphers. The whole plot of her novel revolves around the arrival of a Mole lady named Beryl and her companion, a Rabbit, to live in a cottage on the River Bank. Beryl is a character of absorbing interest, a true addition to Grahame’s original quartet:

Beryl was an Authoress. […] Every morning from nine until lunchtime Beryl wrote, and from three in the afternoon until teatime she revised her work, writing it out again clean.

Beryl provides literary conversation and companionship to the poetry-loving Rat, and a tart response to the bachelor certainties of Badger. The loveliest chapter of Johnson’s novel, which perfectly catches the tone of Grahame’s nature-writing and his charm, is chiefly about a bicycle trip Beryl takes by herself:

Mile after mile rolled away beneath the wheels of her bicycle. She felt the changes in the path through the tires: here gravel, there a drying puddle, there earth beaten down iron-hard beneath a slick of sticky mud, across a lawn or field. The path ducked beneath a metalled road bridge. She reveled in the moment of cool, damp darkness, and the sounds overhead of horses pulling a heavy dray, and then a motor-car. “They have no idea I am down here,” she said to herself. “Why, I might be a spy! Or a bandit, setting an ambush. If there were two of us, now. . . .” She thought of writing down a few details that might be useful for the Novel, but she had no paper nor a pen, and — “O, hang the book!” she said, for by then the bicycle had swept her back into the sunlight, which glanced down in patches through the trees. The stately pile of Toad Hall was ahead of her upon the opposite bank — the gold stone and gothic arches, the many chimney pots, the gardener trimming a hedge — all so much more interesting and lovely than any words she could contrive.

At the end of the novel, Johnson delightfully turns the hackneyed theme of the bachelor’s appeal against marriage — which in Grahame and most of his imitators is, in reality, the man’s fear and distrust of women — on its head, by having Rabbit reject Toad’s hand for satisfying reasons:

Rabbit turned back to the Toad, and with a tiny curtsey said, “— but I must decline your very kind offer.”

“But — !” said the Badger, faint but pursuing. “Your good name!”

The Rabbit gave a little shake. “O, that! No, Toad’s a very good sort, but I have no wish to be trammeled with a husband.”

“‘Trammeled’? ‘A very good sort’?” Toad said, puffing up. “This is all you feel for me? When I have offered you my hand, Toad Hall, and my heart?”

The Rabbit shook her head. “It is very good of you, indeed it is! But no. No husbands for me!”

The River Bank, though one of the shortest sequels to The Wind in the Willows, struck me as by far the best of them all. This is no surprise, since Kij Johnson is an accomplished infiltrator of other writer’s fictional worlds, most famously in The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe (2016), which does for H. P. Lovecraft what The River Bank does for Kenneth Grahame — it is an homage and imitation that also gently but firmly spotlights the profound deficiencies of the original and nudges open its world in ways that make it richer and deeper.

¤

One of the most striking features of The Wind in the Willows is its episodic form. Each chapter feels like a short story until the last third of the book, where the imprisonment of Toad, his escape, and his quest to reclaim his overrun estate comprise a tight narrative over the course of multiple chapters. This is undoubtedly an artifact of the book’s composition history. The end — the Saga of Toad, let’s call it — was composed first, in the bedtime stories Grahame told to Mouse. The earlier chapters, which basically concern the friendship of Rat and Mole, were composed after he had been convinced to turn the stories into a book. And the two extraordinary chapters of mystical longing — “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn” and “Wayfarers All” — were written last.

The book is a kind of pearl, whose nacreous layers grew up around some fundamental wounds. Grahame’s biographer observes that, of the four characters at the heart of the novel, Mole, Rat, and Badger seem to represent various aspects of Grahame’s own personality, while Toad, who is presented mostly from the outside, represents an exterior and impenetrable personality — perhaps his son. I can believe this speculation, if for no other reason than because only Toad is unburdened with secret hurts. When things go wrong he breaks down into loud wailing and immediate despair, but the moment he’s out of his scrape, his cloudless, childlike joy returns. By contrast, Mole is oppressed by a sense of his own inadequacy, haunted by the home he left; Rat longs for the sea and sublimates his unattainable desire in bad poetry; and Badger’s age, solitary living arrangements in the ruins of an ancient Roman city, and dour habits suggest he is the last relic of an old River Bank society that is passing away. This set of hurts almost exactly mirrors Grahame’s own condition: he was haunted by the loss of his childhood home, tortured by longing for the unachieved dream of Oxford and a literary life, and disapproving of the modern world in which he found himself. The book comprises a paean to oblivion, which finds its climax in the pantheistic mysticism of “The Piper At the Gates of Dawn.”

A baby otter, Portly, has been lost somewhere in the river. Rat and Mole decide to join the hunt for the little creature, and they manage to find him on a small island. As they approach the island, they hear snatches of a strange, heart-breaking music. The Rat says:

I almost wish I had never heard it. For it has roused a longing in me that is pain, and nothing seems worth while but just to hear that sound once more and go on listening to it for ever.

On the island they find Portly — sheltered by The Piper himself, the god Pan, in whose presence Mole and Rat have an ecstatic mystical experience. They collect Portly and head home,

[but] as they slowly realised all they had seen and all they had lost, a capricious little breeze, dancing up from the surface of the water, tossed the aspens, shook the dewy roses, and blew lightly and caressingly in their faces; and with its soft touch came instant oblivion. For this is the last best gift that the kindly demi-god is careful to bestow on those to whom he has revealed himself in their helping: the gift of forgetfulness. Lest the awful remembrance should remain and grow, and overshadow mirth and pleasure, and the great haunting memory should spoil all the after-lives of little animals helped out of difficulties, in order that they should be happy and light-hearted as before.

I suspect that Grahame alludes here to his own sense that his life had been spoiled by a “great haunting memory.” The sad error embodied in his book is the idea that forgetfulness is a surety of happiness. He projects this desirable quality upon Toad, who is forgetful not merely when a demigod blesses him with oblivion, but as a feature of his own psychology; and Grahame projected this same quality onto his son, by the pretense that Mouse was not disabled and by dishonest praise of intellectual capacities he did not possess. Nothing could more decisively refute Grahame’s thesis about the connection between oblivion and happiness than Mouse’s suicide.

I like to think of the extraordinary flourishing of book-length, published Willows fan fiction as a correction of Grahame’s fundamental error: in our return to his world, we do him the honor of disbelieving him, of insisting upon the healing properties of memory, of honesty, and of the patient binding of wounds.

¤

Robert Minto is a writer and philosopher. He lives in Boston.

¤

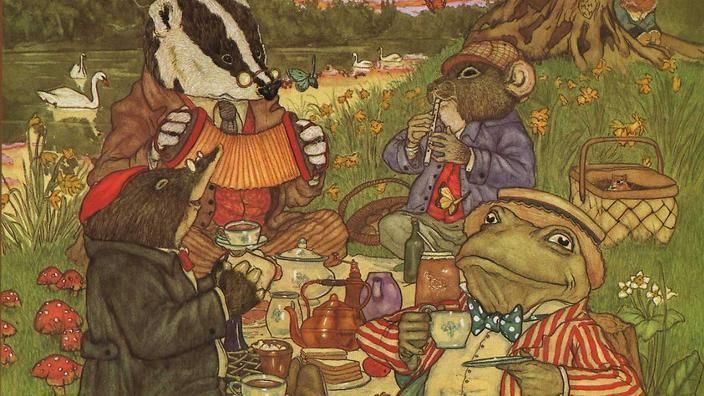

The cover illustration for The Wind in the Willows used in the header of this article is by Michael Hague.

LARB Contributor

Robert Minto is an essayist and storyteller. His complete bibliography and his monthly newsletter about reading can both be found at robertminto.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Badgers in Platemail: On Brian Jacques’s “Redwall” Series

YA author Daniel Jose Ruiz reflects on his favorite children’s series.

What Lies Beneath: Jennifer Bell on Her “Uncommoners” Series

Cleaver Patterson interviews children’s fiction author Jennifer Bell.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!