“The Wondrous Legacy of the Ciliary Hair”: On David George Haskell’s “Sounds Wild and Broken”

Jayson Greene reviews David George Haskell’s new book, “Sounds Wild and Broken: Sonic Marvels, Evolution’s Creativity, and the Crisis of Sensory Extinction.”

By Jayson GreeneJuly 27, 2022

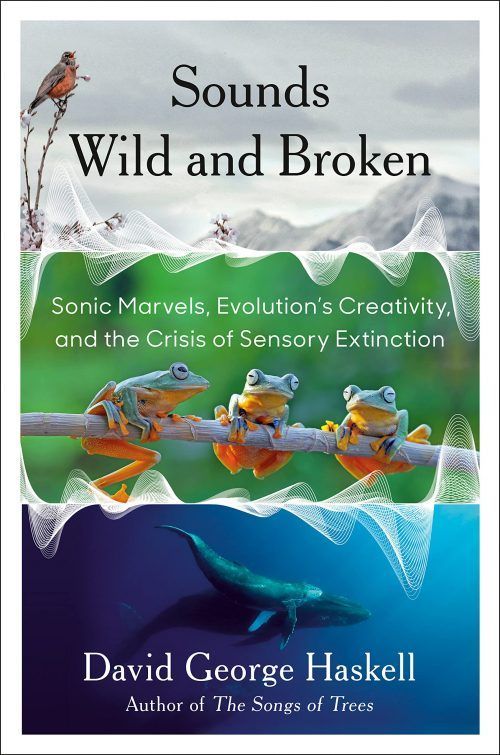

Sounds Wild and Broken: Sonic Marvels, Evolution’s Creativity, and the Crisis of Sensory Extinction by David George Haskell. Viking. 448 pages.

FOR NEARLY THREE billion years, life on Earth was mute. Nothing sang, buzzed, or croaked. Ocean animals swished through the water, but their noises were incidental, reached no one, and served no communicative purpose. The only sounds — wind, rain, thunder — merely emphasized the vast emptiness.

If not for the miracle of cilia sprouting from our cell walls, life on Earth might have remained this way. As ecologist David George Haskell describes it, the cilium was life’s first sense organ, our first antenna into the beyond. Ciliary hairs functioned like crude motors, but they also absorbed surrounding sound waves, passing information into the cell walls. On a microscopic level, cilia represent life’s acknowledgment of a larger world, teeming with others and demanding navigation.

In his new book, Sounds Wild and Broken: Sonic Marvels, Evolution’s Creativity, and the Crisis of Sensory Extinction, Haskell returns us to this primordial state of ciliary hairs motoring about. Those same cilia line our nostrils and live inside our inner ears, he reminds us, and thus deliver us our most ethereal experiences. “When we marvel at springtime birdsong, an infant discovering human speech, or the vigor of chorusing insects and frogs on a summer evening,” he writes, “we are immersed in the wondrous legacy of the ciliary hair.”

A professor of biology and environmental studies, Haskell has made it his life’s mission to reenlist the senses in the fight against nature’s despoliation. In his Pulitzer Prize–nominated The Forest Unseen: A Year’s Watch in Nature (2012), he trained his gaze on one square meter of old-growth forest in Tennessee for 12 months, recording everything he saw. In Thirteen Ways to Smell a Tree (2021), he evoked the scents of leaf litter, woodsmoke, and pine resin as keys to fighting deforestation. In Sounds Wild and Broken, he has chosen hearing as his portal, and the book is a soaring panegyric not just to the human ear but also to the auditory equipment of every living being. Over the course of the book, you will be invited to wonder if birds listen “better” than humans; you will be asked to imagine hearing apparatuses spread evenly across the skin of fish. “I’m a fish talking in air, strutting and breathing on land, yet experiencing the sea through trembling hair cells in coiled watery tubes in my ears,” he writes in the first chapter, and what follows is a sustained encouragement to identify ourselves as walking, talking fish.

The stakes, as he gently reminds us throughout, couldn’t be higher. “[A]t least 20 percent of the world’s plant species are threatened with extinction,” and current estimates peg the extinction threat for marine species at 25 percent. Deforestation rages unabated as emissions from fossil fuels continue to rise. The environmental ravages are unlike anything in human history. “Our culture is on track to remake itself and much of the Earth by century’s end,” he writes, as he tries every trick he knows to make us feel the loss. He spatters the page with onomatopoeia: Carolina wrens go tea-keetle-tea-kettle, rhinoceros hornbills crac crac-CRAca cra-CRA, frogs ack ack or yup! yup! His prose is so rhapsodic that it occasionally tips over into goofiness, as if David Attenborough had taken an edible before entering the recording booth. Haskell wants us, above all, to listen, to use our glorious ciliary hairs for good. Those twitching hairs delivered us from pond scum, after all. Maybe, if properly attuned, they can deliver us from catastrophe.

The story of sound, as Haskell tells it, is the story of motion, of ever-larger communities, of increasing distances crossed by ever-more-sophisticated methods of communication. He traces the roots of communicative sound all the way down to the microscopic ridges on the first prehistoric insects, which scientists believe generated a rasp when rubbed together. In his telling, creatures didn’t dare open their mouths, or rub their chitinous wings together, until they were certain they could escape any unwanted attention their songs might bring. In other words, the very first thing we decided to do, once we were reasonably certain we weren’t going to be eaten alive, was to sing.

Over and over again, Haskell demonstrates how sound and motion are connected, how sound begets life. The explosion of flowers in the Cretaceous period brought insects, which buzzed with heightened intensity as they navigated, hunted, and courted one another. Birds, drawn to the insects as a rich food source, sang out their signals. As the environment grew more clamorous, new voices were drawn into the chorus. “Sound is generative,” Haskell argues, and thus the absence of sound will have effects on life that we cannot predict.

Haskell is a big believer in the notion that sound can foster empathy. Sound literally binds us, he argues: “Nerve to nerve we connect, sound wiring us into ‘the other.’” The key to sustaining a “destructive economy,” he writes, is “sensory alienation.” The antidote, then, must be sensory immersion. Once we hear the busy clatter of snapping shrimp silenced by the roar of an outboard motor, goes the argument, we cannot unhear it. It was the widespread dissemination of sound recordings of humpback whales, he notes, that moved humanity to save the animals from extinction. We heard their cries and decided they were worth preserving.

It’s beautiful, Haskell’s devotion to his ears. As a working music critic for 15 years and counting, I find myself moved by his belief that listening to the voices of others might inspire us to empathy. But our ears are also servants of our peculiar minds, which sneakily edit and shape what we hear based on unconscious sensory biases. We selectively choose the voices that matter, the ones worth preserving or amplifying, and our selection is biased irretrievably toward the sounds of our own kind. Haskell acknowledges this problem repeatedly throughout the book, pointing out that “[w]e have approximately one hundred times more genetic information available from birds than from insects,” not for lack of available insect DNA but for lack of scientific interest. “Icarus flew on wings of feathers, not of insect exoskeleton,” he notes smartly. “The Christian Holy Spirit descends as a dove, not a cicada.” The species that capture our imagination tend to reap the rewards of human attention.

As I read the book, I noted with guilt how much more engaging and delightful it became for me the closer the sounds in question got to the human voice. I enjoyed reading about the bubbles formed by the claws of snapping shrimp, but the slight unease I felt hearing their chatter silenced by an outboard motor bore no comparison to the anguish and grief at reading about the destruction of bird habitats. Sounds Wild and Broken is thus another book about the power of empathy that winds up demonstrating empathy’s limits.

Haskell acknowledges and tries to address this problem. He demonstrates how foreign birdsong can sound alienating, harsh, or guttural to nonnatives. The staccato, percussive style of Australian songbirds sometimes grates on European ears, while Australians traveling abroad often confess to a keen sense of displacement when surrounded by more melodious birdsong. In each case, the listeners were pining for the sensoria of their youth; Haskell quotes a 2020 study that shows listeners only finding birdsong relaxing when it’s familiar to them. This gets at the ultimate barrier to empathy — everything we truly learn about the world, we learn once and most forcefully in our earliest years.

Haskell is alive to all the evidence working against his hypothesis. A music lover, he adeptly outlines the history of colonialism embedded in the types of wood used for instruments. A biologist for decades, he is alive to the patriarchal biases of science, and how scientific data has been used to prop up white supremacist conclusions. He acknowledges that humans routinely create oases of peace and calm — suburban developments, spas, golf courses — while ignoring the ravages these oases create elsewhere.

But perhaps because the stakes of losing all that we love remain so unbearably high, Haskell holds fast to his belief in our senses as moral agents. He is never more eloquent, or affecting, than when he is arguing, against all the available evidence, that humans are capable of listening to other voices, and of learning from them. “[C]oncern follows closely on the heels of empathic connection,” he insists. Definitions of beauty may be tyrannically subjective, but “[b]eauty inspires us to connect, care, and act.” “A deep experience of beauty draws together genetic inheritance, lived experience, the teachings of our culture, and the bodily experience of the moment,” he declares, in a tone almost of defiance.

Sound, Haskell argues, is the vehicle best suited to capture the attention and thus the concern of humanity. In its very ethereality, sound is the closest simulacrum for our experience on Earth. Paint dries on a cave wall for posterity, but the ripples the Neanderthals sent into the air have long since dispersed. The fossil records tell us everything except how the creatures sounded. “Vocal folds do not fossilize,” after all, and neither do the air bladders of fish, which means the qualities of these creatures’ speech fades into history just like the sounds themselves. We don’t even know what we’ve never heard, which gives a fresh urgency to the preservation of the creatures making sounds today. “Listening gives us an experience of the value of temporary existence unlike any other bodily sense,” he writes. “The songs of a blackbird or the music of an orchestra recapitulate the journey of sound in the cosmos: out of nothing, into brief life, then a return to silence.”

In the future, the world will be a far stiller place. Never before will we have existed on a planet with so few other sounds of life. In many corners of the earth, air will cease rippling, whether or not there are cilia hairs nearby to detect it. The loneliness we experience will be unlike anything in our evolutionary history.

This is where books like David George Haskell’s Sounds Wild and Broken prove most powerful. The sustained elegiac note rings far longer than any of the particular examples of loss he cites. Our proximity to loss whets our appreciation for life, and as despoliation and loss continue, the tenor of our mourning will surge in intensity. The music celebrating the dying earth will grow more beautiful, and maybe, one day, we will truly be moved enough by what we hear to save what can still be saved.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jayson Greene is the author of the memoir Once More We Saw Stars (2019) and a contributing editor at Pitchfork. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and elsewhere. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Evolution Wars: The Saga Continues

Jessica Riskin offers a revisionist history of evolutionary biology.

In the Belly of the Beast: How the Whale Encapsulates Modern Ecology

Ferris Jabr plumbs the depths of “Fathoms: The World in the Whale,” the new book by Rebecca Giggs.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!