Triptych image: "Rules of the Universe"

Image Credit: Maureen Selwood

EDGAR ALLAN POE IS EVERYWHERE. The Following, featuring murders based on Poe, occupies prime time Monday on Fox, and memories of Long Beach Opera’s production Philip Glass's The Fall of the House of Usher linger on in San Pedro. There’s a story, true as far as I know, that when Roger Corman was in the middle of shooting House of Usher (1960) — one of his eight Poe adaptations, most of them starring Vincent Price — he heard that a house had just burned down in the Hollywood Hills. He quickly assembled a small crew, and filmed Mark Damon, as Philip Winthrop, riding a horse through the ruined landscape. These shots form the opening of the movie.

Since Poe’s story is set in an unspecified gothic neverland, who’s to say it didn’t look much like the Hollywood Hills? But in fact Corman’s opening sequence shows a landscape so generic that you could easily think it was filmed on a backlot or sound stage. There’s certainly no way you could, by watching the movie, locate that devastated landscape, no way you could go there, poke around, and say that you’d walked where this fictional house once stood. I find that a great shame.

¤

I was in Abney Park Cemetery, in Stoke Newington Church Street, London, following distantly in the footsteps of Edgar Allan Poe. He very definitely set foot in Stoke Newington Church Street because that’s where he attended the Reverend John Bransby’s Manor House School, between 1817 and 1820. And he may very well have walked into Abney Park, although at the time it was simply a park and not until 1840 did it became a nondenominational garden cemetery and arboretum, complete with a chapel built in Dissenting Gothic style.

Nevertheless, there’s a Poe-ish frisson to be had in the cemetery: overgrown and uneven graves, broken columns and statuary covered in real or carved ivy, huge dead trees, the chapel now in ruins. And at least on the day I was there, a couple of graffiti marked the inside of the boundary wall, one saying “Turn Back” the other “We R Legion.” Yes, honest.

Poe’s old school is now a wine bar, the Fox Reformed, and there’s a bust of Poe mounted on the wall, high enough to be safe from all but the most determined demented vandals. The bust was unveiled by Steven Berkoff, famous for playing Hollywood villains and psychopaths, but he also created and appeared in his own stage and TV versions of The Fall of the House of Usher and “The Tell-Tale Heart,” which is no doubt why he got the unveiling gig.

As I stood looking up at the bust of Poe, I happened to meet a friend of a friend, a former rock group manager now a local librarian, and explained what I was doing there. “Ah,” he said, unprompted, “you’re on a drift.” Thus the language of psychogeography spreads around the world like a contagion.

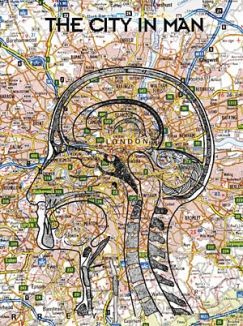

In the dime stores and bus stations, people may not necessarily be talking about the Situationists (the begetters of psychogeography), but in the hipper university departments they seem to talk of little else. Sometimes described as anarchists, sometimes as Libertarian Marxists, the Situationists (there were never more than ten of them) were active from the late 1950s to the early 1970s in France. They and their leader Guy Debord (who essentially expelled the other members until he was the only one left) devised various strategies to subvert capitalist society, believing (quite reasonably it seems to me) that individuals should construct the “situations” of their own lives.

Psychogeography was one of these strategies, “the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals” (Debord, “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography” 1955). The chief means of “study” was the dérive, or drift, “a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences. Dérives involve playful-constructive behavior and awareness of psychogeographical effects, and are thus quite different from the classic notions of journey or stroll” (Debord “The Theory of the Dérive,” published in the magazine Situationiste Internationale, 1958).

Sometimes I’m not so sure that it really is “quite different” at all. The idea of walking through cities and looking at things in new or unexpected ways is surely as old as cities themselves. But the practice did reach a kind of apotheosis in 19th century France with the notion of the flâneur, literally stroller, with overtones of the man about town, the urban explorer, and idler.

Baudelaire championed the flâneur:

The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd. For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite. (“The Painter of Modern Life,” first published in Le Figaro in 1863.)

Since Baudelaire was also the translator of Poe, it was natural that he should look for evidence of the flâneur in Poe’s work, and he found it in the story “The Man of the Crowd” written in 1840: one man follows another through the streets of London for a very long time, for no very good reason. It seems that a mystery will ultimately be solved, that a revelation will be made. But in the end it isn’t. Paul Auster, eat your heart out.

As far as I can tell “The Man of the Crowd” has never been turned into a “real” movie (though IMDB lists a video short), which is frankly a surprise. What was Roger Corman up to? Didn’t he think the story measured up to his usual high standards?

¤

If you get off the train in Woking, in Surrey, 20-some miles southwest of London, a place memorialized in the Jam’s song “A Town Called Malice,” the streets around the station lead you naturally through a short pedestrianized street, and at the end of it you’ll come upon a 23-foot high, stainless steel statue called Martian Walking Engine. If this isn’t too overwhelming you may also notice a metal cylinder half-lodged in the ground, and that certain paving stones have biomorphic metal shapes set in them, officially referred to as “bacteria slabs.” You’re looking at a sculpture, or I suppose installation, by Michael Condron, commemorating H.G. Wells’s novel The War of the Worlds.

In 1896 and 1897 Wells and his second wife Jane lived in Woking in a modest but comfortable semidetached house in Maybury Road, just a few hundred yards from the station — a commuter’s dream. It was here that Wells wrote The War of the Worlds, serialized in Pearson’s Magazine in 1897, the same year, coincidentally or not, that Dracula was published.

Wells’s mornings in Woking were spent walking, or sometimes cycling, in the nearby countryside; in the afternoons he wrote. Legend has it that he was walking with his brother on one of those mornings, and they imagined how it would be if Martians suddenly descended on this quiet English scene and set about destroying it: thus was born The War of The Worlds.

¤

The current wisdom is that The War of the Worlds (and Dracula, too, for that matter) is a response to certain late 19th century British imperial anxieties. While the British Empire exerted its influence around large parts of the world, London, its capital and at that point the largest city the world had ever known (4.7 million inhabitants by 1900), was uniquely vulnerable to what it saw as the pernicious morals, manners, and in some cases actual diseases brought in by “aliens.” Wells, however, is at least somewhat on the side of the angels. The unnamed narrator recognizes that the Martians treat the people of Britain with the same indifference and contempt that British colonizers direct against “inferior races” (Wells’s terms, though not in quotation marks, alas).

¤

In Woking I walked from the Martian statue to Wells’s house in Maybury Road. There are houses on only one side of the street. The railway line runs along the other, on an embankment at about bedroom window level. There’s a fence and some shrubby trees between the street and the tracks, but the trains must be far more visible than the residents want them to be: lace curtains and high hedges are common. Wells’s house had been modernized a little more than many in the street, but there’s a limit to how much people can, or want to, change a basic Victorian semi.

My guess is that Wells wouldn’t have found so very much to surprise him in today’s Maybury Road. Yes, there was a big yellow-painted garage offering “trade price tyres direct to the public” and although there wouldn’t have been many cars in Woking when Wells lived there — he lived until 1946 — he’d have known all about the motor age.

There was a modern printing works in the street too, but printing would not in itself have been mysterious to Wells, and in any case this one was named Optichrome, which sounds oddly Wellsian and 19th century to me. He might have been more surprised by a dress shop, Libas: Elegant Asian Design, and the Body and Beauty Studio, run from adjacent houses, but it was hardly the kind of shock Wells’s Time Traveller had to deal with. As visions of the future go, this was a very moderate one, and by Wells’s standards positively unimaginative.

¤

The War of the Worlds contains two deeply disturbing and enduring and, I’m tempted to say, archetypal narrative tropes. First, Wells imagines the destruction of his own neighborhood, even his own street:

I closed the door noiselessly and crept towards the window. As I did so, the view opened out until, on the one hand, it reached to the houses about Woking station, and on the other to the charred and blackened pine woods of Byfleet. There was a light down below the hill, on the railway, near the arch, and several of the houses along the Maybury Road and the streets near the station were glowing ruins.

Then, after the Martians, like many new immigrants, have moved from the outskirts to the center, into London itself, the native population there moves out, is evacuated in this case, and Wells is able to describe what the narrator, who sneaks back in, calls “Dead London.”

Why was I wandering alone in this city of the dead? Why was I alone when all London was lying in state, and in its black shroud? I felt intolerably lonely. […] I came into Oxford Street by the Marble Arch, and here again were black powder and several bodies, and an evil, ominous smell from the gratings of the cellars of some of the houses.

This is great stuff, isn’t it? Haven’t we all imagined the destruction of our own homes? Haven’t we all imagined being the only inhabitant of an abandoned city? Of course there are some people for whom these situations have been real rather than imaginary, although only in fiction have they had to contend with Martians or indeed vampires.

The War of the Worlds is not exactly a vampire story, but the Martians are definitely vampires of a sort.

They did not eat, much less digest. Instead, they took the fresh, living blood of other creatures, and injected it into their own veins. I have myself seen this being done, as I shall mention in its place. But, squeamish as I may seem, I cannot bring myself to describe what I could not endure even to continue watching. Let it suffice to say, blood obtained from a still living animal, in most cases from a human being, was run directly by means of a little pipette into the recipient canal …

¤

The terrors, and the plot, of The War of the Worlds are transferable, can be reset far beyond the boundaries of London and England. Orson Welles’s 1938 radio version moved it to the East Coast of the United States, with the Martians landing in Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, before moving on to Manhattan. A couple of later radio broadcasts created local versions, and by some accounts local panic, in Chile and Ecuador. Steven Spielberg’s 2005 movie purported to be set, at least initially, in New Jersey, though parts of it were filmed all over the country, including (according to IMDB) one scene shot at the corner of Witmer Street and Ingraham Street in Los Angeles, streets that I walked all the time when I used to have business at the Good Samaritan Hospital a couple of blocks away. I had no idea at the time.

However, the 1953 movie version, produced by George Pal, directed by Byron Haskin, is the only one to set the action resolutely in California, with the Martians touching down in the fictional town of Linda Rosa (actually the real town of Corona), before moving into Los Angeles and destroying some very recognizable landmarks, City Hall included. Again, the hero, who now has a name, Dr. Clayton Foster, played by Gene Barry (you know he’s smart because he wears glasses; you know he’s tough because he wears a leather jacket), at one point finds himself alone in a dead city.

Inevitably it’s the special effects and the gorgeously designed Martian flying (not walking) machines that really make the movie, but those scenes of people trying to bribe or fight their way onto trucks to get out of the city, and the hero finally being left in the deserted downtown streets, are extremely effective and affecting. Some of this looks as though it was filmed on a backlot, but parts are definitely shot in a genuinely empty downtown. In one shot the street signs for Eighth Street and Hill are clearly visible in the foreground, with a sign for The Fruit of the Loom on a building behind them.

The current wisdom is that Pal’s movie is a response to certain mid-20th century American imperial anxieties. America had won the “real” war, was the strongest power on the planet, yet found itself in the middle of a Cold War against what had been one of its allies. Having the atomic bomb delivered neither security nor control, and in the movie it is completely useless against the Martians.

Whether Pal’s Martians are vampires is hard to tell; it’s not the kind of movie to be much concerned with the digestive system of the invaders. But, staying true to the novel, victory comes far more by good luck than good management, when the Martians are “slain by the putrefactive and disease bacteria against which their systems were unprepared,” as Wells puts it.

¤

Those who found this an unrealistic or overoptimistic outcome might have been more persuaded by Richard Matheson’s novel I Am Legend, published a year later, in 1954: a post-apocalyptic novel, in which the world has been destroyed by a virus, and the vast majority of the world’s population turned into vampires. The hero, Robert Neville, lives in his own house on Cimarron Street, in Gardena, having destroyed the houses on either side to stop the predators getting to him. Each day he goes out to plunge stakes through the hearts of sleeping vampires, and in the evening he returns home, listens to classical music, drinks whisky sours, and occasionally reads Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

“The strength of the vampire is that no one will believe in him.”

Thank you, Dr. Van Helsing, he thought, putting down his copy of Dracula. He sat moodily staring at the bookcase, listening to Brahms’ second piano concerto, a whisky sour in his right hand, a cigarette between his lips.

It was true. The book was a hodgepodge of superstitions and soap-opera clichés, but that line was true; no one had believed in them, and how could they fight something they didn’t even believe in?

Things do not end well for Robert Neville, bacteria do not save him, even though eventually he becomes “a new superstition entering the unassailable fortress of forever.”

¤

Richard Matheson was a solid and successful Hollywood writer. He’s still very much alive and still writing, though not so much for the screen. He’s best known in certain quarters as the writer of The Twilight Zone’s “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” and he was responsible for another 15 episodes as well. His movie credits include The Incredible Shrinking Man, Spielberg’s Duel, and a 1974 TV movie titled Bram Stoker’s Dracula, starring Jack Palance.

Like The War of the Worlds, Matheson’s I Am Legend contains something archetypal: a single, alienated man battling resolutely against a diseased world even though it would be so much easier simply to submit. His home is vulnerable but intact, a place of (comparative) safety, even as the monsters howl at the door.

Will it surprise you that Richard Matheson once lived on Cimarron Street? In an interview with John Scoleri for the website The I Am Legend Archive, he said:

The idea for I Am Legend came to me when I was about 16. I went to see Dracula and the thought occurred that, if one vampire was scary, a world filled with vampires would really be scary. I did not write the book until 1952. We lived in Gardena, California and I set the story there, using our house as Neville’s house.

I, and others, have made attempts to find the number of the house where Matheson lived on Cimarron Street, and it seems he simply doesn’t remember. Cimarron is a long street, stretching from above the 10 to well below the 105, and there’s also a Cimarron Avenue and a Cimarron Way in Gardena, which actually fit better with the geography of the novel, and although I enjoy an aimless drift more than most, a dozen-mile expedition to an unspecified address in Gardena was too nebulous even for me.

I don’t think it’s an insult to say that Matheson is an ideas man rather than a literary stylist (some would say the same about Wells), which is also to say that I Am Legend is a great basis for a movie. It’s been filmed under its original and other titles, and was an “inspiration” (i.e., no money changed hands) for George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), now regarded as a game-changing zombie movie, though the word zombie is never used, much less vampire.

Like The War of the Worlds, I Am Legend is a moveable feast. A 1964 version, titled The Last Man on Earth, starred Vincent Price and was filmed in the outskirts of Rome. The 2007 Will Smith version, I Am Legend, was set resolutely in New York City. But it’s the 1971 version, titled The Omega Man and starring Charlton Heston, that’s acquired cult status, and like many a cult classic it has strong elements of camp. The anxieties here seem to be about what we might as well call the Sixties. The streets are not filled with vampires — they don’t suck blood — but with cloaked hooded figures, in fact victims of germ warfare. Sometimes they resemble Charles Manson followers, sometimes revolutionary Luddite hippies. They refer to themselves as the Family, they call each other Brother, and they’re certainly racially integrated, although all wearing the same white face of the undead.

Charlton Heston’s Neville doesn’t listen to classical music or read Dracula, but he does “keep up standards” by sitting around on Sunday evenings in his emerald green velvet smoking jacket, sipping a highball, and listening to soft jazz, like an end times Hugh Hefner. The location used for Neville’s house is actually on the Warner Brothers lot; you can also see it in the title sequence of Friends when they frolic around in the fountain: the same fountain in which Neville ultimately dies.

Outside his house, however, he moves in a real Los Angeles that is still largely recognizable today, over four decades later. He drives more than he walks, but he’s on foot enough of the time to make following in his footsteps a possibility, and — full disclosure — various online movie obsessives have done some sterling detective work already, making the job that much easier.

And so I began my drift in pursuit of Charlton Heston, or Robert Neville. I admit that some conflation took place.

Everyone says how much downtown Los Angeles has been revitalized in recent times but there are still some pockets of amazing desolation and vacancy. Even on a weekday afternoon you can turn a corner or walk through an alleyway and find you’re the only person on the street, which admittedly is by no means the same as being the last man of earth, though some judicious camera angles and editing could no doubt make it appear that way.

Early in The Omega Man Neville crashes his Ford XL convertible and abandons it, simply walking away to find a replacement, gun in one hand, gas can in the other. He walks up Santee Street, which becomes a dead end north of Eighth Street. The building across that dead end is still there, though it’s been spruced up to no end since the movie, painted a creamy beige color with a bright red fire escape, and it’s now part of Santee Village, “a community of seven loft buildings.” This is the Downtown Renaissance, no doubt, but I have photographs to prove that the street was absolutely empty when I was there: not even a man with a gun and a gas can.

A few blocks along Eighth Street is the Olympic movie theater where Robert Neville obsessively watches Woodstock, memorizing the lines, and staring ambivalently at a performance by Country Joe and the Fish. A purveyor of ornate home furnishings now operates in the building — “Everything Must Go 50%–70% Off” — but the marquee is still there, ready to display any coming attractions. And if Neville had gone just a couple of blocks further still, along to Hill Street, he could have stood exactly where Gene Barry did in The War of the Worlds, and where I stood too. The Fruit of the Loom sign is just a memory but the building that displayed it looks solid as ever.

My walk finally took me to the Water and Power Building, also known as the John Ferraro Building, at First Street and Hope. It’s an elegant, late 1960s, 16-story glass and concrete box, hard to see from many of the nearby streets, because it’s tucked in behind Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall, and of course in the normal run of events you’re not likely to go there unless you have some business concerning water and power. In itself it looks unchanged from the movie, though there are some new skyscrapers on the horizon. Neville is there to run laps apparently, though he may be joking about that, but he’s also there to kill the infected inhabitants of the city, and when you think of the number of floors and offices in this building alone, you realize what an impossible task he had on his hands.

Walking around the building, which is surrounded by water in a kind of moat, the chances are that you’ll be alone, and with the sunset tinting the building’s glass walls an intense, warm orange, you might think that being the last man on earth wasn’t such a terrible thing; just as long as the “vampires” weren’t about to appear.

Why exactly do I do this? What does it mean to walk in the footsteps of authors, actors, and their characters, exploring the streets where they lived or walked, seeing how things are, how they’ve changed or stayed the same? Is it a form of psychogeography, or research, or really just a low level form of tourism, not so very different from buying a map of movie stars’ homes?

The answer to all these questions is: I’m never really sure. There are some days when I think that psychogeography itself is just a fancy word some people use to feel better about being strollers and idlers. Sometimes I think this need for a walking “project” is downright superfluous, that it’s an excuse or an affectation. Why not walk for the sake of walking?

There are other issues too. I’m always a little suspicious of those articles or books, or even (god help us) organized tours, that invite us to walk through, say, Dickens’s London or Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles. For one thing in London and Los Angeles, and in any other big city, you’re always walking in the footsteps of millions of people besides your chosen author. These cities belong to everybody and anybody. To see a city through a single text (or lens) is bound to be reductive. More crucially, I think, any city that exists in a book or movie, however “authentic,” is always first and last a fictional construct. You can’t walk there any more than you can walk in the Emerald City or Utopia.

And yet, and yet ... I was pretty well pleased when I discovered that Raymond Chandler and his wife Cissy had once lived in an apartment block on Greenwood Place, Los Feliz — walking distance from where I live. They were there in the early 1930s, when Chandler was writing his first crime stories for Black Mask. I duly walked over there, and felt not simply as though I was walking in Chandler’s old street, but rather as if I were living in a Chandler novel. I expected a “gunsel” to come out of the building and slug me. Within the confines of my imagination I was delighted with that prospect.

At this point I find it pretty much impossible to walk across Westminster Bridge in London, without “seeing” those early scenes in Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later when the protagonist staggers around a beautiful, eerie, and thoroughly empty London. The effect is even more intense if the bridge happens to be packed, as it so often is, with commuters streaming into or out of the city.

And I’m not sure that it was essential for me to make a literary pilgrimage down to Shepperton, shortly after J.G. Ballard’s death, to walk along his old street, to stand outside his empty house, and simply stare, but I did. And as a result I know that Ballard’s living arrangement in Shepperton was amazingly similar to the one H.G. Wells had in Woking: a modest semidetached house, easy walking distance from the rail station — a commuter’s dream. And just as Wells wrote The War of the Worlds in the suburban serenity of Woking, it was in Shepperton that Ballard wrote the short story “The Autobiography of JGB,” in which the hero wakes one morning to find that he’s the last man on earth. These things are worth knowing. These things give me immense pleasure, and if they’re not strictly necessary, and certainly not strictly literary, I feel good about having made these expeditions, about having made these small discoveries while walking.

And that is why, for all my reservations, I really do wish that I’d been able to walk in the Hollywood Hills and find the spot where Roger Corman shot those opening scenes of House of Usher. You know who wrote the screenplay for that movie? Richard Matheson. Who else?

¤

LARB Contributor

Geoff Nicholson is a contributing editor to the Los Angeles Review of Books. His books include the novels Bleeding London and The Hollywood Dodo. His latest, The Miranda, is published in October.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Barbarians at the Wormhole: On Anthony Burgess

A Clockwork Orange and The Wanting Seed are minor masterpieces of the dystopian subgenre and are unusually clear in their anxieties

Bodice-Ripper, with Werewolves: Anne Rice's "The Wolf Gift"

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!