“The Stories in Songs”: A Conversation with Luis Chaves

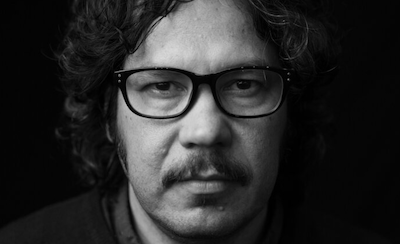

Carlos Fonseca in conversation with Luis Chaves.

By Carlos FonsecaFebruary 19, 2022

THERE ARE AUTHORS who like to keep things neat, making sure each book is a different project, separate and distinct from what came before. There are others, more playful, who construct their body of work as if it were a matter of assembling a vast web where life and literature weave around each other. Luis Chaves seems to work like this. Poetry, prose, diary entries, crónicas: everything fits within his books.

When he decided to leave behind his studies in agricultural engineering to focus on writing, it was poetry that first caught his attention. It has been almost 25 years since he published his first poetry collection, El Anónimo (1996). Since then, his more than 10 published books have consecrated him as one of the most original and versatile voices within Latin American literature. He has won important prizes like the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Poetry Award and the Fray Luis de León Poetry Prize and has been invited by prestigious residences in Berlin and Nantes. Chaves’s magic is to have done all of this while writing unpretentious books that refuse to raise their voice too loud. Detached from the grandiose and solemn literary pretense of many of his contemporaries, Chaves has often mentioned that his work springs from a simple double gesture of writing in his diary a record of everyday life, just to erase it a couple of minutes later. I like to think that, in his case, his poignant writing springs from the traces that are left behind. Traces that, with time, begin to sketch the impressive radiography of a common man’s life.

“Here’s an attempt at reconstructing / everything with only a few elements,” we read in “False Fiction,” one of the poems collected in Equestrian Monuments, his first book to be published in English, translated by Julia Guez and Samantha Zighelboim and published by After Hours Editions. This poetic statement, in its unassuming insightfulness, is characteristic of Chaves’s method and of his achievement. Playing with the remainders that refuse to surrender to oblivion, his books reconstruct quotidian scenes from lives that might have otherwise gone unnoticed. Luis Chaves is the attentive witness that renders each of those poetic moments finally visible.

¤

CARLOS FONSECA: You begin this book with an epigraph from Charles Simic that states that “the time of minor poets is coming,” while saying goodbye to Whitman, Dickinson, and Frost. Tell me what this “time of minor poets” means for you?

LUIS CHAVES: It is actually a whole poem, yes. I remember reading that poem by Simic for the first time many years before Equestrian Monuments (the Spanish original version was published in 2011) was even an idea of a book for me. I remember how it felt very close, how I related to this guy, late at night, looking for poems (written maybe in notebooks or loose printed pages) in his children’s room, trying not to wake them up. Looking for those poems because he wanted to share them with his guests, other poets of course (you would never do that with the friends that love you in spite of you being a poet), and I remember thinking something like, “I guess I know what Simic is doing here with this text, underneath this portrait of powerless individuals there is something else, they are erratic, vulnerable men, trying to hold on to something they have no idea where to find.” And so I felt I was there in that same room where the poem takes place.

Tell us a little about your beginnings as a poet and your arrival to literature.

Since I can remember, I was always following the stories singers told/sang in that kind of music that tell stories. Simple words, simple stories. I also learned to read with my grandmother (my mother worked so I stayed home with her) before starting preschool and the adults around me realized that “this little fellow likes to read,” for they found me reading any kind of printed paper I found in the house. My parents were not intellectuals (actually, far from that) nor did they have the habit of reading, so what this little guy read in the house were newspapers, the manual of the recently acquired blender, etc. I haven’t stopped reading since. One day I decided I wanted to do the same, write books and publish them (not the same thing, we all know). I didn’t follow a formal education in literature; for many years, there was no difference for me between poetry and fiction (or other genres). These separated categories or tags or whatever we want to call them I discovered later. People say he/she is a poet, or he/she is a writer. Two different categories. I know this is how it has been decided, but in my head there is just one: a writer, someone who writes.

I remember you telling me once about your involvement in poetry magazines back in the day. It was interesting to hear how those magazine put you in touch with writers and poets from all over Latin America.

Looking back, it is almost unbelievable. Year 1998: Picture a scenario with rudimentary internet access (we were using ultra slow connections, I mean Latin American Slow) that was enough for my Argentinian friend and writer Ana Wajszczuk and me to start end edit a poetry magazine that was distributed both in San José and Buenos Aires. We wanted to focus on “another poetry,” meaning poetry that did not need to sound or look like poetry (which was the canon then, at least on this side of the world). The magazine was called Los amigos de lo ajeno, and it was printed from 1998 to 2004.

What were your readings back then? Did any Anglophone poets influence you?

I didn’t have a formal education on literature so I read without a plan, methodology, or structure. One book led me to another. Always poetry and always “narrativa” (not making the distinction between fiction/nonfiction, which are foreign categories), a little bit of philosophy, “nuevo periodismo,” religion, and sports chronicles. But also, and at the same level, always fascinated by the stories in songs.

As for Anglophone writers of my beginnings, let us try some name-dropping: Dickinson, Sexton, Plath, O’Hara, Rexroth, Ginsberg.

Any Latin American poets who were particularly influential to you?

This question is always difficult to answer, but let’s try: Nicanor Parra, Juan Gelman, Ernesto Cardenal, Alejandra Pizarnik, Enrique Lihn, Blanca Varela, Raúl Gómez Jattin, the “poesía de los 90” in Argentina, Antonio Cisneros, Juana Bignozzi.

Your poetry always feels close to life, close to the quotidian rather than grandiose. What guided you in this approach to writing?

I like to read all kinds of poetry, even the kind of poetry written for poets. I enjoy it, I learn from it. But when it comes to my writing, there are two things: 1. I write conscious of my boundaries, my limitations, “this is how far I can go.” 2. I guess all I want is to, one day, write a poem that has that mysterious power that good songs have. Songs say things (powerful, wonderful, moving) that would sound corny in a poem.

“Here is an attempt at reconstructing / everything with only a few elements,” we can read in the poem “False Fiction.” Do you think poetry works like that?

I wish I knew how poetry works! That worked, I think, for that poem.

Tell us a bit about the genesis of Equestrian Monuments — how did it come about and what place does it have within your many books?

There is a short foreword in the original EM in Spanish (published October 2011). There I say something more or less like this: “The book was built gradually (‘se fue armando’) in a way as Simic’s poem/anecdote does, with a man that enters his daughters’ room late at night, waking them up as he looks for loose poems in the dark. The poems were thrown away in the last cleaning, the man is me and from the moment I entered my daughters’ room until I go back to the living room to read poetry to my friends a whole decade has gone by.” So, the book was not thought as such, a book with a theme or a specific music, breathing, or rhythm. It comprised poems written as far back as 2002, others were pieces published in newspapers, and one of them was dated October 2, 2011 (the same year and month of the book’s publication).

This is the first book of yours to be translated into English, if I am not mistaken. Tell us a little about the experience of working with your translators.

Some poems had been published in magazines and newspapers (POETRY, Boston Review, Circumference, The Guardian, Guernica, PEN Poetry Series, Asymptote, Springhouse), but as a book this is the first time. All of them translated by Julia Guez and Samantha Zighelboim, to whom I will be grateful all my life. I mean this, it is not a protocolary comment. Their work has been meticulous, serious, and attentive of the “time” of poetic writing. The process has taken more than a decade for there was no hurry, just like the group of poems collected in the book. Julia and Samantha’s translation can be condensed as: No urgency, every word weighed. And, most important, making their own version of the poems that were originally written in another language, a Spanish form that is specific to the region it belongs to (there is no standard Spanish, only in movie subtitling). Borges used to say that translation is more civilized than writing.

Your work always mixes genres. I love reading your prose books as if they were poetry and your poetry books as if they were prose. And, to add to that, you are always experimenting with extra-literary genres: the diary, the photo album, the chronicle, inventories, and so on. What interests you about those sorts of mixtures?

As a matter of fact, what happens is that I do not think in advance. This can be good, this can be bad also. But this is how it is. And I said before, of course I am aware of the existence of genres, but deep inside my head, there is only writing.

I like this idea: there exists only writing. I think nowadays poetry is one of the genres with the greatest amount of freedom. I remember a friend once telling me that only poets who have freed themselves from the idea of writing a best seller can really do whatever they want. Do you feel the same?

I have never thought of it that way, but I totally agree and will use your friend’s insight from now on whenever asked about this subject! (“As Carlos Fonseca’s friend once said…”) The fact that you are writing a genre that almost only people who also write poetry read is liberating. In other words, no one cares so you are doing this because you really want/need to do it.

You once wrote, I think in your book Iglú, that you aspire to write “an infinite book that must fall to pieces or undo itself as one reads.” That’s a beautiful image. Is that how you conceive of your own writing?

I liked the idea of a book, the texts inside, melting as we read them. Like holding an ice cube in the palm of your hand. I like this image.

¤

LARB Contributor

Born in San José, Costa Rica, Carlos Fonseca was named one of Bogotá39’s Latin American writers under 40. He is the author of the novels Colonel Lágrimas (2014) and Natural History (2017), and of the book of essays, La lucidez del miope (2017), which won the National Prize for Literature in Costa Rica. He teaches at Trinity College, Cambridge, and lives in London.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“America Is a Myth”: A Conversation with Natalie Diaz

Natasha Hakimi Zapata interviews Natalie Diaz about “Postcolonial Love Poem.”

Star Vehicle: On Translating Poetry

Polish poet Tomasz Różycki reflects on his craft of translation, in an essay translated by Mira Rosen-thal.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!