The Ruminations of a Booster

Paul Buhle reviews Bill Schelly's memoir "Sense of Wonder: My Life in Comic Fandom — the Whole Story."

By Paul BuhleSeptember 22, 2018

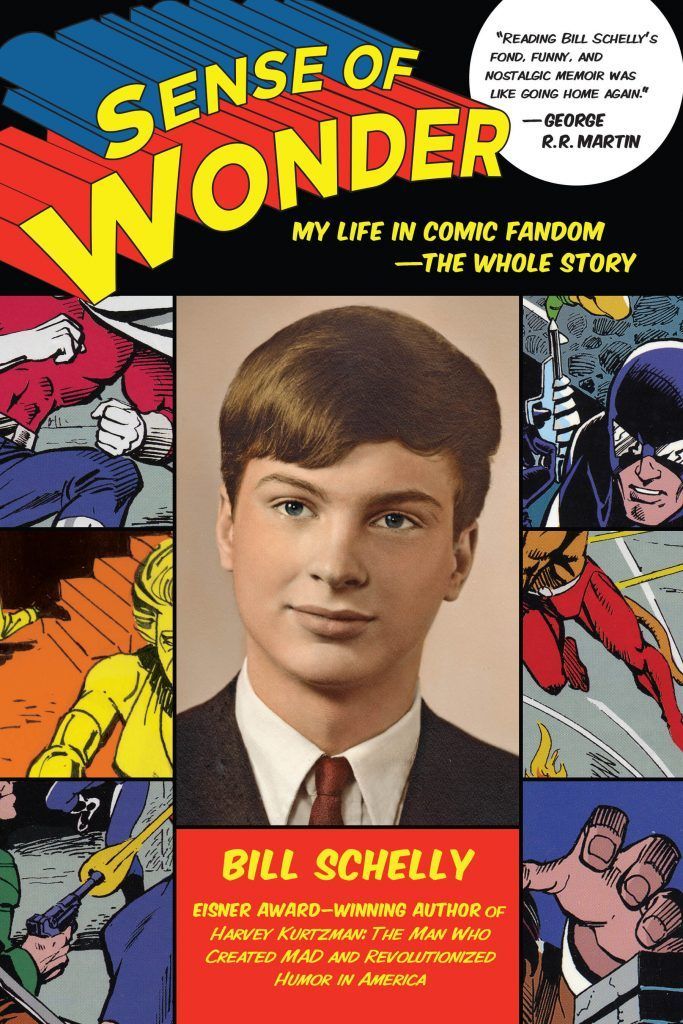

Sense of Wonder by Bill Schelly. North Atlantic Books. 392 pages.

WE HAVE RECENTLY entered the age of comic art canonization. The teaching of college courses on comics, from small seminars to large lecture courses, has naturally accompanied museum exhibits and award ceremonies. It has just as naturally prompted the emergence of journals, textbooks, and monographs specializing in comics studies. Prestigious university presses have new series on a variety of comic art topics and individual artists. This is a rather startling development in a world previously occupied mostly by nonprofessionals, including self-described “fans,” whose biographies and assorted monographs on the greats and the forgotten ranged from the amateurish to the very fine, and were often graced by lavish illustrations. The nonacademic volumes around the art of EC comics masters alone — Will Elder, Wally Wood, Harvey Kurtzman — constitute a historic-visual library of sorts, without which no history of comic art could be complete.

There is much to be gained, as well as considerable confusion, from the field’s more recent academic turn. Comics have, as Art Spiegelman reminded readers decades ago, become recognized art just as the daily comic strip, the principal means of financial support for artists, has faded away with daily newspapers themselves. With this shift, comics readers, especially young readers in college, may feel validated instead of scorned as time-wasting weirdos. On the other hand, the very creation of a canon, already a tendency in the fan writing, further focuses attention upon the valued few. This not only consigns much good work to obscurity, but also draws the canonized works away from their contexts in ways that constrain our understanding of them. Is Robert Crumb’s work, or that of Bill Griffith, really comprehensible without a knowledge of underground comix as an artistic, social-cultural phenomenon with dozens or even hundreds of artists and many styles? Are we now to deconstruct some popular favorite of decades ago, with freshly minted terminology? In every case we must ask, what does this academic blossoming leave behind?

The last question is particularly pertinent in the case of Bill Schelly’s Sense of Wonder: My Life in Comic Fandom — the Whole Story. Schelly is a self-described fan extraordinaire. Like hundreds of others, he began self-publishing as a teen, sending out his own mimeographed or, later, offset zines to others in the fold, mainly exchanging copies until he had built up enough readers to sell them. Some of those others, those whose names we are likely to recognize — Crumb springs to mind — went on from collecting, publishing, and distributing fan mags to becoming artists themselves. Schelly, who did plenty of his own drawing along the way, and at one point actually considered a comic-art career, decided that he had reached a dead end along those lines. Sagely, he turned to a series of jobs for various entities, including the federal government and the Seattle Counseling Service, an institution serving the city’s LGBT community. But he continued to write about comic books and film, and became a prolific and respected independent scholar.

Many pages in Sense of Wonder describe Schelly’s personal life, including his recognition of his sexual identity, the threat of the draft circa 1970, his work, his partners, his experiences fathering two children for and with lesbian friends, and so on. This part of the book is a relaxed exploration of a middle-class fellow’s experiences in the liberal Northwest from the 1970s more or less up to the present. Readers need to feel sufficiently interested in Schelly to want to read through the details, or at least to appreciate them amid the saga of his fandom. And I was. Like the memoirs of an academic historian — I have been an academic historian — they lack what we might call novelistic drama. No murders, no international intrigue, not even a psychotic breakdown!

Schelly does not seem to have drawn any striking conclusions from this life of work and friendships. Perhaps he leaves us to do so. If he has suffered deep depressions, he keeps them to himself, and this may be a measure of how far gay acceptance or self-acceptance has come in his lifetime. His personal relations, from those with his parents to those with his boyhood friends’ mothers who occasionally turn up later in his life, are affable.

But Schelly’s personal life provides a context for the books of criticism that he has written. These include biographies of Otto Binder (a publisher of 1930s sci-fi pulps who turned to comics and co-created Captain Marvel), John Stanley (the uncredited artist of Little Lulu who labored in obscurity in a print shop until rediscovered by fans), and silent screen comedy film star Harry Langdon. Then there are the fannish studies of fandom, including The Golden Age of Comic Fandom and the Comic Fandom Reader. Where is the professor who has been more energetic or assiduous in the pursuit of the seemingly obscure?

We come back, finally, to the inner stories of the zines and their creators. These stories have gained a new significance with the rise of the Comic-Cons, including the San Diego spectacular now taken over by film studios (but keeping the Eisner Awards ceremonies as a sidebar). At the local and regional level, these conventions can still be agglomerations of young people, disproportionately but not solely male, many selling their wares to onlookers who, just as likely, produce or dream of producing zines of their own. The shift of unpublished art online seems not to have marginalized this phenomenon, and it may be the social element that remains vital. How else are hobbyists and would-be professionals to meet each other?

Schelly offers many more small gems of detail along the way of his own path through fandom. If these will not interest every reader, they still provide a rich sense of interplay between the occasional professional, who mostly graduates into superhero comics, and the amateurs who remain behind. What outsiders may find baffling is the intensity, but the same intensity is the clue to who the participants have been and remain, as the generations pass and the professors take a little interest in a developing field of scholarship.

¤

LARB Contributor

Paul Buhle co-edited the outsize oral history tome Tender Comrades, with Patrick McGilligan, en route to several other volumes on the Blacklistees with co-author Dave Wagner, including A Very Dangerous Citizen, the biography of Abraham Lincoln Polonsky. He is the author or editor of 35 volumes including histories of radicalism in the United States and the Caribbean, studies of popular culture, and a series of nonfiction comic art volumes. He is the authorized biographer of C. L. R. James.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“Johnny Appleseed” and the Revision of American Masculinity

Ashley Rattner reviews Paul Buhle and Noah Van Sciver's graphic biography "Johnny Appleseed."

Creating a Comics Canon

Russ Kick’s "The Graphic Canon of Crime and Mystery" is, for now, the most sustained anthology of comic art in the English language.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!