The Readers’ Reader: On Michael Silverblatt’s “Bookworm”

Chris Via reviews the selection of literary interviews gathered in “Bookworm: Conversations with Michael Silverblatt."

By Chris ViaMarch 31, 2023

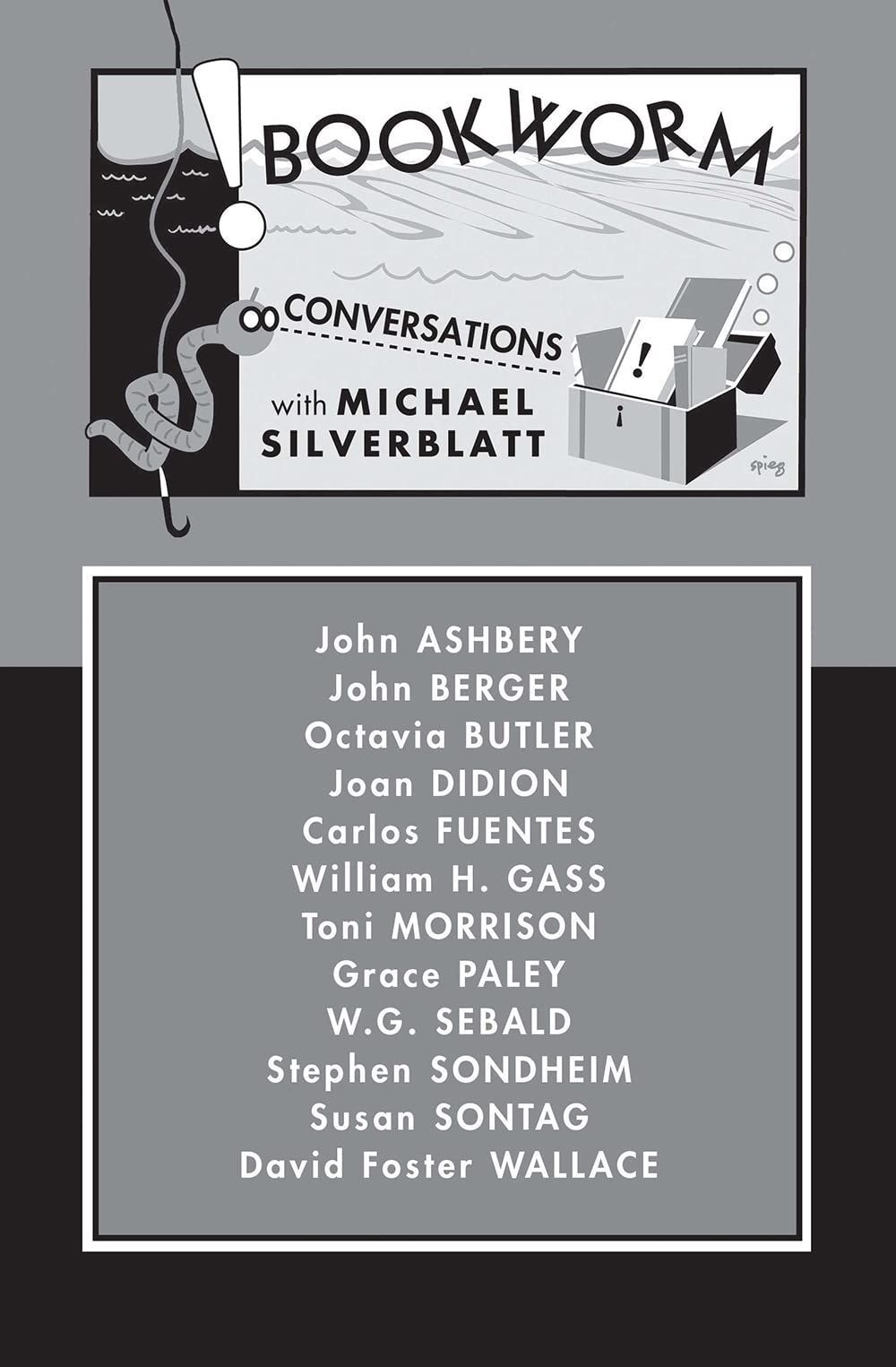

Bookworm: Conversations with Michael Silverblatt by Michael Silverblatt. The Song Cave. 432 pages.

MY FIRST CONVERSATION with Michael Silverblatt lasted only four hours. It was late on my side of the phone, but we could have easily talked until daybreak on the East Coast. We spanned a vast range of topics that December night. I offered my inevitable spiel about how big a fan I am, which included all the usual platitudes and (botched) attempts at preening. We talked about books, of course, and writers we love; about Silverblatt’s luminous university days in Buffalo; about his hero and mentor John Barth; about soirées with the likes of Michel Foucault and Donald Barthelme and Susan Sontag; and about his list of “secret books” (all of which I knew I had to purchase and read immediately). In a moment I’d like at the top of my résumé, I cited a book with which Silverblatt was not familiar (I know!). He immediately began hunting down a copy, but it was out of print. Going against deeply rooted personal book ethics, I mailed him my beloved edition, asking him to please ignore the juvenile marginalia scrawled throughout. Like the conversations on his legendary KCRW talk show Bookworm, this phone call was an education unto itself.

This chat inaugurated a year’s worth of regular phone calls until we met in person for breakfast at Kings Road Café in Los Angeles. In those early days, I was tongue-tied and neurotically self-aware. As Bookworm listeners know, Silverblatt has an insatiable appetite for thorough consideration and inspection, and I felt as vulnerable and exposed as one of Nabokov’s butterflies. He posed trenchant questions that forced me out of my bashful reticence, yet his incisiveness was so gentle that he made me feel, well, special and important. Just as we hear him on the radio, with his unique voice, careful pacing, and infectious cadences, so he is when off-air. It’s not an act, not a persona. He intimidated me, yes, but he also gave me confidence and put me at ease. By August, when he requested it, I sang “Happy Birthday” to him—something I’ve never done for anyone, ever. (I cannot sing, and the mere suggestion of it recalls a humiliating moment in seventh-grade chorus.) Later, I realized that he had done with me precisely what he does so well with writers: he let me shine and helped me sing.

With 28 minutes for each show, one of Silverblatt’s challenges is to begin the discussion with an observation or question as salient as a great book’s opening sentence. The writer is immediately hooked and so are the listeners. Mario Vargas Llosa once wrote about this in El Pais, Spain’s daily newspaper, referring to Silverblatt as “el gusanillo de los libros” (“the little worm of the books”): “No sooner did he start to speak when I was glued to what he said and, almost immediately, I was conquered.” This glorious conquering to which Vargas Llosa refers is a condition well known not only to guests of the Bookworm program but to the program’s listeners too—serious readers who come to great works of art to have the limits of their consciousness conquered, the earth turned for new growth. What a boon, then, to have, in Bookworm: Conversations with Michael Silverblatt (2023), a small but sumptuous sampling of what Vargas Llosa meant by his admiring words.

The project to bring a collection of the Bookworm transcripts into print was already underway when I was asked to be an early proofreader, a privilege I gratefully accepted. Now, nearly a year later, I have read and listened to these conversations so many times that the voices have taken permanent residence in my head. Despite being a longtime listener and relistener of the program (the show’s archives are available on the KCRW website), and now a reader and rereader of these particular conversations, I find that the insight packed into each show defies the economic law of diminishing marginal utility. That is, each consumption of this product increases my satisfaction with it.

In the first conversation in the book, Silverblatt interviews John Ashbery, a poet known for being reticent in public. Silverblatt starts the show by proclaiming Ashbery a “connoisseur of wonderlands,” to which Ashbery responds: “Alice in Wonderland is one of the first and major books I ever read.” A palpable openness in Ashbery immediately follows. In their discussion of the 2009 collection Planisphere, Silverblatt confesses: “At first, I didn’t know what to do with your poems at all except to reread them. They were so mystifying to me.” What reader of Ashbery has not experienced this? This confession of bewilderment and incomprehension by such an experienced reader comes almost as a relief. Then Silverblatt grabs our attention with his next statement: “I reread them for years without understanding that I already understood them.” The key, then, is in rereading. As he demonstrates repeatedly in these conversations, some literature resists being understood in conventional ways, and one of the joys of rereading is to discover the unconventional ways a poem or story operates.

The long conversation in John Berger’s home in France is the closest we will ever get to eavesdropping on two philosophers in the olive groves of ancient Greece. Along with Berger’s books, virtually all facets of the humanities are examined. In the course of the exchange, Silverblatt forwards a theme that runs through many of the talks in Bookworm: “I think that fiction is one of the places where we go for silence, a worded silence, words that amount to or return to silence. And the best fiction maybe even aspires to a kind of muteness.” Berger weighs Silverblatt’s thoughts, then agrees—an extraordinary moment when something deep within a reader touches something deep within a writer. The concept of reading as a “worded silence” has given me a new, more eloquent way of thinking about my own life with books.

The talk with Berger is the only conversation in this book that took place outside the Bookworm program. Thanks to the Lannan Foundation, the video is viewable online and is worth seeking out for the added value of Silverblatt’s and Berger’s contemplative silences, emphatic expressions, wild gesticulations, and the endearingly quaint ritual of shared cigarettes—the smoke, in effect, a third presence at the table, curling around and sliding against invisible clouds of unspoken thoughts emanating from these two sages.

The episodes with Octavia Butler exemplify how to approach books outside one’s usual preferences. Silverblatt admits to Butler from the start that he depends on others to bring important genre titles to his attention. Now, having read her books, he addresses the possible misnomer of labeling them science fiction. Butler agrees, saying, “Kindred really isn’t science fiction, just because there’s no science in it.” Silverblatt then proceeds to discuss the extensive research that went into that novel. We learn that Butler used the money from her previous publication to finance a trip to Maryland to do research on the Antebellum South. She researched, among many other things, the way people did laundry during that era, so meticulous is her attention to detail. Excited with her findings, she called her mother to tell her about it, and her mother recalled her own mother doing laundry that way. It’s a touching moment elevated even further by Butler: “I hadn’t realized how near history was.”

The conversations with Joan Didion are as multifaceted as a crystal. In fact, Silverblatt says of her 1996 novel The Last Thing He Wanted that you “have to handle the book with jeweler’s calipers, […] the pieces have become so small. And the more you read it the narrower the microseconds of chronology have become, and the more you come to understand has been simultaneous in it.” As in his conversation with Butler, Silverblatt’s perceptiveness about the analytical design of Didion’s books gives us a rare insight into how the writer’s physical tools can shape their work: Didion explains that she had recently switched from longhand to a computer, the rigidity of which forced her to become more logical.

The episodes on The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) and Blue Nights (2011) explore the tragic background of the passing of Didion’s husband and the extended hospitalization (and eventual death) of her daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne. About the latter book, Silverblatt notes that the memoir “goes as far to the edge […] as it’s possible to go.” “I think it can only be put along with King Lear,” he continues, “and some of the other works of approaching madness or approaching the end.” Of the book’s structure and shape, he says that he noticed it went from a fugue state of grief to a fugue itself. Didion affirms that it felt like music while she was writing it. Silverblatt also points to the Greek tragedians. Didion agrees again, saying that the idea of tragedy “has been with me since early childhood. The first things I read really were the Greeks.” Amidst the poignancy of such heavy topics, there are endearing moments of genuine laughter, a reminder of the very real and deep human connection that Bookworm offers.

The five Carlos Fuentes conversations are a virtual curriculum of the humanities. Topics range from mythology to philosophy, Mexico’s ancient history, Machiavelli as the presiding philosopher of the world (Fuentes’s words), Dostoyevsky, Balzac, Stendhal, interpretation, surrealism, Miguel de Unamuno’s fiction, the much-abused term “magical realism,” Christopher Columbus’s likening of the world to his mother’s breast, the state of contemporary Mexican politics, economics, publishing, readership, and much more. The reach of Silverblatt’s learning in these episodes is staggering, and never far from his keen poetic eye. At the start of the episode on Fuentes’s 1992 novel The Buried Mirror, for example, Silverblatt says that the book is “your Altamira bull in the cave of history.” Fuentes points out that there is also a human hand depicted in the Spanish cave, and Silverblatt says that it’s amazing to think of those paintings vanishing with oxygen. Fuentes reformulates this idea with panache: “We are plastic mythological heroes who arrive and vanquish the bull through our breathing”—a stunning statement that compresses many thoughts and feelings. The only remark that could rival Fuentes’s is the one Silverblatt makes next, thankfully immortalized now in print.

In the conversation with William Gass about his 1999 book Reading Rilke: Reflections on the Problems of Translation, we get to witness Silverblatt, who has clearly fallen in love with Gass’s work, talking to Gass about how Gass fell in love with Rilke’s work. Hearkening back to the conversation with Berger, Silverblatt extends the concept of the “worded silence” to another form of ghostliness in literature, saying that Gass “suggest[s] that […] when you read Rilke’s novel [The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, 1910], you’re reading a haunted house, you’re reading a convocation of ghosts.” This proposition is then bolstered with a poetic flourish that only Silverblatt could reach for:

Your work on metaphor and image is profound and seems to trace in Rilke a movement that takes a trajectory from voice to groove, the groove on a record, the reproduced voice when that groove is played becoming a ghost-like image. There is a sense that ghost and metaphor interpenetrate in their purpose, that people in fiction are not so much characters as traces, atmospheres, locations for the inter-surfacing of light.

This “inter-surfacing of light” turns out to be exceptionally perceptive, as Gass later talks about Rilke learning from Auguste Rodin “the importance of light as a living principle in any surface. You break up the surface, you pick up reflections, you make every part of that surface alive.” Referring to Rilke’s imagery, Silverblatt says that “it’s as if the job of a writer is to take the dying world and not lie about the fact that it is a dying world but bring it to life in a constantly animating prose.”

In the conversation about his 2012 book Life Sentences: Literary Judgments and Accounts, Gass dissects a passage from Henry James’s The Wings of the Dove (1902) in order to reveal its architecture. Later, while giving an example of how Gass’s essays have helped improve his own reading, Silverblatt quotes from memory the opening sentence of James’s novel, virtually singing it to emphasize its “ascending c’s.” This inspires Gass to remark:

[I] had to relearn how to read slowly […] to savor, to try to understand how out of all the choices that, say, James had in making a particular paragraph—so many words could have been used—every time he uses one he takes away these chances to use others until finally he has a system of words put together that is almost indestructible because you can’t change anything without ruining everything.

Silverblatt responds: “We’re always hearing ghosts when we’re reading, not just the ghost of what the writer left out, but the ghost of what the writer heard.” Reading, then, is also learning to notice the ghosts of the worded silence.

A key moment for me occurs in their discussion of Gass’s 1995 novel The Tunnel. Addressing the topic of difficulty in fiction, Gass states that literature is made to be experienced, not explained. It’s about the journey, not the destination. And Silverblatt, alluding to the book’s tunnel imagery, says it is a novel that one “lives in.” This is such a simply stated idea, but it has resonated with me for years. I don’t read to get through a book; I read to live in a book, to make it a part of my life. I treat reading a book as I would a serious relationship that I want to work out.

In the episodes with Toni Morrison, Silverblatt shows us how to use literature as the impetus for deep conversations across history and geography. The two-part interview on Morrison’s 2008 novel A Mercy explores not just the literary treatment but the realities of racism, slavery, sexism, and inequality. Morrison says, “It’s exhilarating just to attempt to struggle with the enormity, the immensity, not just of the subject matter, but of the continent [of North America]. Trying to look at this very strange, very bountiful, but also very dangerous place.”

The occasion of the 1998 film adaptation of Beloved (1987) allows Morrison and Silverblatt to affirm that old book lover’s maxim that “the book was better.” Of course, the discussion is in no way flippant or disparaging of film as a medium. But Morrison asserts that “you have a major void in a movie […] you don’t have a reader; you have a viewer. And that is such a different experience.” This crucial difference hinges on the fact that “the encounter with language is such a private exploration.” Later, Silverblatt responds:

[W]ords are the inadequate clothing of that experience when you’re reaching the heart. Up until that point, the writer’s choices, word by word, are immensely important. When you reach the heart, no word can be correct. You’re talking about an experience that is close to a mystical experience.

It’s no surprise that the Los Angeles Times was so impressed by the Beloved episode that they had it transcribed to print it themselves.

The Grace Paley episode captures a unique and tender moment in Bookworm history. When Paley finishes reading one of her beautiful stories, Silverblatt unexpectedly asks if he can hold her hand. (Paley’s surprise recalled my own when asked to sing “Happy Birthday.”) The intimacy that follows feels tangible to the listener. Silverblatt tells her that her stories are like the composition of a sonnet. The “compression is so enormous,” yet there’s “a whole life in there.” This leads Paley to concede that “part of the task I’ve assigned myself, although I didn’t know it at first,” is “to tell as much about life and the world as I could in a short space.”

One of the great pleasures of reading W. G. Sebald is his style, so it is deeply fulfilling that much of Silverblatt’s conversation with the author is dedicated to examining his prose, tracing its influences back to 19th-century German literature, and connecting it to Sebald’s appreciation for naturalist and scientific writing. At the end of this spectacular discussion, Silverblatt summarizes their talk in a breathtaking passage that bears quoting in full:

It was once explained to me that there was in German prose something called das Glück im Winkel, happiness in a corner. [I think that your radical contribution to prose is to bring] the sensibility of tininess, miniaturization, […] to the enormity of the post-concentration camp world. [So] that a completely or nearly forgotten prose tone is being brought into the postmodern century, and that the extraordinary echo, almost the immediate abyss that opens between the prose and subject, is what happens, that automatically, ghosts, echoes, trance states—it’s almost as if you are allowing the world to howl into the seashell of this prose style.

For me, this captures the essence of what sets Bookworm above any other program about books: Silverblatt’s manifold powers as a reader. He recalls a concept from German prose that most of us don’t know; he poetically situates Sebald’s work historically and highlights its idiosyncrasies; and he reconnects their earlier discussion about the ghostliness of the prose and the shrouded, foggy atmosphere of the pages, using imagery that hasn’t left me since I first heard it. This is why listening to (or reading) each of these conversations is like following a sacred commentary on the pleasures of reading a great book.

The depth and breadth of Silverblatt’s literary knowledge is, of course, the stuff of legend. But in the two conversations with Stephen Sondheim, we find that Silverblatt can speak with fluency about forms beyond fiction and poetry. When the 1971 musical Follies comes up, for example, Silverblatt talks about his experience in the audience on the show’s opening night, quoting from memory various lyrics with admiration and brio. Of the 1970 musical Company, Silverblatt pegs its form as “based on revue,” which Sondheim affirms. When Silverblatt asserts that the love song between two men in 2003’s Road Show was “a first for semi-traditional Broadway musical,” Sondheim offers that La Cage aux Folles (1983) was the real first, to which Silverblatt’s command of both musicals allows him to respond: “But there, La Cage, that was the subject. This arrives at something with difficulty.”

I grew up in rural Virginia in the 1980s and ’90s, so my exposure to theater was severely limited. The closest I got was watching Bing Crosby in White Christmas (1954) with my mother each December. In general, my natural proclivities tend toward novels, poetry, and literary criticism, so it’s a testament to the power of these conversations with Sondheim that I would find myself frantically seeking out books of his collected lyrics, willing to pay any price necessary. I felt as if I were impoverished, malnourished, missing out on an enormous and important part of our culture, but I also felt empowered and enthused to start my newfound education.

In his conversation with Susan Sontag about her 1999 novel In America, Silverblatt points out that, after the prologue, the “consciousness dawning” is “initiated with a slap.” And the end of the novel comes with the recipient of that slap saying, “Please stop.” “This is consciousness as enunciation,” he says. Sontag is so exhilarated by this perception that she jumps in, literally apologizing for cutting him off, and says she wrote the prologue very quickly and was pleased with it, but then couldn’t figure out where to go with the book. Eventually it came to her that it should begin with a slap. “Were you aware it was a birth slap?” Silverblatt asks. “No, I wasn’t,” she says. “That’s kind of wonderful.”

The four Sontag episodes offer too much to briefly summarize, but the show about Sontag’s preface to the 2001 edition of Leonid Tsypkin’s book Summer in Baden-Baden (1982) deserves mention. The serendipitous account of how Sontag stumbled upon this small Soviet Jewish novel and helped bring it into print in the United States is the stuff of fiction itself. Sontag recounts her inauguration into the world of literature when she discovered the display of Modern Library books in the back of a stationery store in Tucson, Arizona. Silverblatt and Sontag, good friends at this point in their lives, go on to describe their game of challenging one another to find unknown masterpieces. By the end of this episode, you will have purchased a minimum of four books without regret.

One of the most popular episodes of Bookworm is Silverblatt’s first interview with David Foster Wallace, right on the heels of the publication of Infinite Jest in 1996. The very first observation Silverblatt makes is that it seems that the book was written in fractals. With cautious optimism, Wallace tersely asks him to expand on this, and Silverblatt describes how “the way in which the material is presented allows for a subject to be announced in a small form. Then there seems to be a fan of subject matter, other subjects, and then it comes back again […] and […] I said to myself, ‘This must be fractals.’” Foster Wallace, clearly impressed, says, “I’ve heard you were an acute reader,” then explains how the original draft was based on a Sierpiński gasket, though in the book’s final form the structure is a lopsided fractal. It is doubly impressive that Silverblatt not only recognizes the complex organization of Infinite Jest, but he also recognizes it in its corrupted state.

But Silverblatt, as always, goes beyond mere recognition of form. “[W]e’re entering a world that needs to be made strange before it becomes familiar,” he says. The book isn’t difficult “for difficulty’s sake; it seemed like immense difficulty being expended because something important about how difficult it has become to be human needed to be said and there weren’t other ways to say that.” Wallace’s response is the literary shot heard ’round the world: “I feel like I wanna ask you to adopt me.” It’s humorous, yes, but it also captures an occasion when a sensitive and discerning reader has recognized, and therefore given validity to, something over which an artist has labored for years in isolation. It’s one of many profound moments in Silverblatt’s long and luminous career.

Waiting for new episodes of Bookworm must be, I imagine, similar to what the eager readers of serialized Dickens and Tolstoy novels felt in the 19th century. Yet I resist listening to a new show right away. These offerings are not to be seized upon like a crazed pie-eating contestant, though they do invite the temptation. No, to me each episode is a special gift that requires dedicated and undistracted time. Each talk contains the promise of a conversation that is disobedient to clichés, devoid of banter and filler, where thoughts about art are exchanged with vibrancy and depth. Even when the guest is a writer I’ve never heard of, I’m convinced by the end of the show that theirs is the most important new book in the world, and to go another day without reading it is to embrace willful ignorance. Most importantly, perhaps, Bookworm reminds me that reading centers my life, and Michael Silverblatt’s words remind me that great books (and great conversations) are never finished, even when one turns the final page.

¤

Chris Via’s work appears in Kenyon Review, Los Angeles Review of Books, 3:AM Magazine, Rain Taxi Review of Books, Splice, The Arts Fuse, and The Rupture. Chris also hosts the growing, literature-obsessed YouTube channel Leaf by Leaf.

LARB Contributor

Chris Via’s work appears in Kenyon Review, Los Angeles Review of Books, 3:AM Magazine, Rain Taxi Review of Books, Splice, The Arts Fuse, and The Rupture. He recently contributed the afterword to Novel Explosives (2021) by Jim Gauer, and in 2018 won honorable mention for Grove Atlantic’s national book review competition, featured on Lit Hub. Chris also hosts the growing, literature-obsessed YouTube channel Leaf by Leaf. He holds a BA in computer science and an MA in humanities.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Question Is My Breath: On Honorée Fanonne Jeffers’s “The Love Songs of W. E. B. du Bois”

Jeffers’s debut novel is a sweeping American epic of family secrets and generational legacies.

A Sibyl’s Eye: On S. D. Chrostowska “A Cage for Every Child”

S. D. Chrostowska’s stories are like dreams that last several minutes yet leave our minds occupied for days.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!