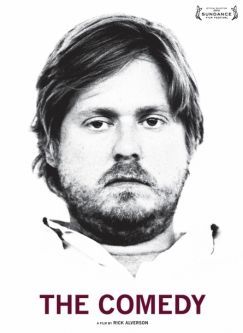

The Queasy Question: On Rick Alverson's "The Comedy"

In Defense of 'The Most Walked-Out Film at Sundance 2012'

By Merve EmreJanuary 18, 2013

FOR MANY INDEPENDENT FILMMAKERS today, “Most Walked-Out Film at Sundance 2012” is a perverse badge of honor, and Rick Alverson's deceptively titled The Comedy wears it with pride. That much seems clear from the film's opening shot: a slow-mo wrestling match between two fat, drunk, and nearly naked men, wheezy 30-somethings whose unlovely flesh swells and falls in time to Donnie and Joe Emerson's soulful 1979 song "Baby." Unlike the sweet young things that Donnie and Joe croon about in the background, Alverson's wrestlers are terrible to behold. They slap each other's fat asses and even fatter bellies and watch, transfixed, as their bodies jiggle under the camera's sepia watch. They spit beer on one another's backs, and gape as unnaturally sharp colors reflect off their own spittle. Silently, they howl. Maybe they laugh, but who can tell, really? The scene closes with the camera on Alverson's leading man Tim Heidecker — one half of the cult comedy team known as "Tim and Eric" — who has tucked his penis in between his legs off-screen. Mangina thus secured, Heidecker executes an expressive arm-flap worthy of any preening ballerina, and for a brief moment, he is lit as radiantly as any wispy black swan wannabe could ever hope to be.

According to reports from Sundance 2012, it was about this time that audience members began fleeing the theater in angry, muttering droves.

¤

This review is, in no small part, a defense of The Comedy against the audience members who voted with their feet and against fuddy-duddy critics like A.O. Scott, who dismissed tout court the film's occasionally grotesque take on entitled, middle-aged hipsterdom. Amidst rumors of the hipster's demise, there's something original, if also glaringly obvious, about The Comedy's premise: hipsters in Williamsburg don't die or vanish into bourgeois obscurity. They age and they age badly. Indeed, for a subculture so relentlessly defined by its sartorial choices — the skinny jeans, skinny T-shirts, and skinny shoes forming the slick outer shell of ironic detachment — the natural give and sag of middle age portends certain, social doom. For those avowed non-hipsters watching from the sidelines, as recent converts to New Sincerity or radical empathy or whatever reactionary turn the mainstream media claims came after irony, the fate of the aging hipster offered by The Comedy must seem like a karmic kick in the pants. As Alverson knows, this is good fodder for social satire. One old, fat hipster may be heartbreaking, but a whole school of old, fat hipsters cycling over the Brooklyn Bridge, sweating bullets, is kind of funny.

I suspect that the twilight of hipsterdom struck a more alarming chord with the audience that packed the Brooklyn Academy of Music's Rose Theater for the film's East Coast premiere than it did with the après-skiers that descended upon Sundance last January. Heidecker and Alverson were at BAM to introduce the film and take questions, but left promptly after someone wearing a dirty beard and last year's Chuck Taylors asked Heidecker, in a bored voice, if Heidecker had a brand new puppy, what would he name it? The lights dimmed, the film rolled, and the audience started to laugh. They laughed through the nudity, they laughed through the beer spray, they laughed through Heidecker's mangina. But they stopped laughing about midway through the film's first spoken bit, an awkward monologue that Heidecker's character Swanson delivers to a male nurse who cares for Swanson's rich, dying father. The subject at hand is the unseemly physical condition known to medical professionals as a prolapsed anus. "Have you ever, have you ever had to deal with a prolapsed anus?" Swanson muses, half to himself, half to the slack-jawed nurse who stares dumbly at his interrogator. "Did, did they teach you that in nurse school? You and the ladies get that lesson? I, I'll tell you what. I'll give you a lesson. A prolapsed anus is when the anus which is a muscle gives out after years of abuse, comes out of the rear and hangs like a, like a, slack bag, tissue, uh, like a purse you might have, a nurse might have. You imagine what it would take to make your anus do that?” By the time Swanson shuts up, not only are very few people laughing, a handful of audience members — myself included — are looking disdainfully at their neighbors, wondering what compelled them to laugh in the first place.

Paying close attention to the dynamics of audience laughter — and paying close attention to how my own reaction to the film morphed from indulgent amusement to queasy skepticism — suggests something new about The Comedy’s brand of critical humor. Alverson’s primary target isn’t the broad swatch of hipster culture, as most reviewers have suggested, or even (more specifically) irony, but rather thoughtless laughter and its vexed relationship to disgust, repulsion, and other responses we might loosely categorize as negative and visceral. In this sense The Comedy sits much closer to Heidecker and Wareheim’s sharp Adult Swim sketch comedy show Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job! and its cinematic offshoot Tim and Eric’s Billion Dollar Movie than it does to other indie films that want to complicate their hipster antiheroes. Like those experimental projects, most of the conversational bits in The Comedy invoke things people try not to talk about in polite company: date rape and its attendant secretions; Adolf Hitler’s irritable bowel syndrome; the superlative cleanliness of hobo cocks (“clean as baby’s breath”); and, of course, the prolapsed anuses of our rich, dying fathers. In each example, a serious issue — rape, illness, poverty, fascism — is besmirched by literal dirty talk, discursively smothered by the shameful things we leak from our bodies: piss, shit, semen. There’s no story, no narrative; just talk, it seems, for the sake of talk. This is standard fare for Heidecker and Wareheim who have cultivated a devoted following over five seasons by riffing on activities like eating pubic hair, soaking in bathtubs full of shit, and “sticking things up our holes.” And although there’s a world of difference between Alverson’s lush visuals and the cheesy copy-and-paste aesthetic that characterizes Tim and Eric’s work — a difference I’ll return to shortly — The Comedy embraces the same stomach-churning subjects that made Heidecker and Wareheim such polarizing figures on the contemporary scene.

Formally speaking, the humor on display in The Comedy is classic travesty: humor that operates by constructing a debased or grotesque likeness of the subject at hand. But as the prolapsed anus monologue makes clear, it’s travesty that wears out its welcome. A joke is offered and laughter elicited, but instead of moving on to the next joke like a good stand-up comedian would, Alverson’s characters beat their material into the ground. They stutter, halt, and repeat the same scatological or sexual premise with such one-sided determination that the metaphysical fabric of the joke begins to unravel into a series of critical questions. Why does this count as a joke? Why is it funny? Why was it ever funny? The self-interrogation is aptly summed up by Swanson’s mean-spirited assessment of another hipster’s comedic sensibilities: “You have these, um, terrific comedic instincts and then you immediately sabotage them with the worst follow-up. You have a terrible sense of humor.”

What we see at work here is not Freud’s famous relationship between jokes and the unconscious, but an uneasy friction between jokes and a heightened sense of comedic consciousness that ends not with laughter, but alienation. There is no complex psychosocial theory of the modern subject here, no grab bag of racial or religious taboos that are subverted through the explosive release of laughter. As Swanson’s critique of his friend’s terrible sense of humor makes clear, the humor of The Comedy is made to self-destruct. The result is an embarrassing revelation: as audience members, we see the utterly formulaic and banal patterns that underwrite almost all humor and, in the process, are distanced from our once-laughing selves. It is only fitting, then, that Alverson and his cast take equally banal bodily functions — everyone poops, or so I’m told — as their primary source of inspiration, even if the reflexivity of the humor largely flattens our initial stirrings of disgust. When the reflexive instability of repetition without difference is folded into the classic gross-out scenarios of life, the result is a brand of comedy that fans and critics of Tim and Eric have offhandedly described as “queasy”: weak, unsettling, and inclined to self-sabotage rather than laugh-out-loud transcendence. Or, to echo Roland Barthes, queasy humor is the “ineffable nonsublime,” the “hard-to-say, hard-to-describe” skepticism that denies laughter its affective expressivity. It is the monologic queasiness of The Comedy that makes it an audience exercise not in comedy, but in criticism of comedy’s conventions.

To call such a style “post-Freudian” is to suggest that the cultural productions we’ve called “funny” from, say, 1970 to the present day have exhausted the taboos we classically associate with humor, particularly the kind that works by airing and deflating repressed anxieties about race, sex, and gender. Dirty talk, particularly for these privileged white men, offers an alternative to a particular strain of identitarian humor that has dominated the cultural consciousness since the rise of extreme stand up comedy. Or, as the comedian Bo Burnham recently explained in the lyrics to his song “What’s Funny?”: “If you’re an Asian comic, just get up and say, ‘My mother’s / got the weirdest fucking accent’ / Then just do a Chinese accent / ‘Cause everybody laughs at the Chinese accent / Because they privately thought that your people were / laughable and now you’ve given them the chance to / express that in public.” In posing the blunt question “What’s funny?” Burnham is really asking a series of more delicate questions. What is the fate of humor after Richard Pryor, Woody Allen, Eddie Murphy, Margaret Cho, Eddie Izzard, and Dave Chappelle? How can a privileged, white man bring heterogeneous audiences together with laughter in 2013 the way Pryor did in 1971 or Chappelle in 2005? Who’s entitled to this kind of humor? This is both the joke and the complaint that The Comedy registers by making self-sabotaging dirty talk a great equalizer — both the lowest common denominator of laughter and its undoing. This, Alverson tells us, is the fate of comedy now that the classic taboos of the America’s cultural melting pot have been done to death in stand-up form, and it’s a more thought provoking claim than anything mainstream comedy has had to offer for quite some time.

¤

But perhaps what makes The Comedy even more stringent fare than Tim and Eric’s sketches is that the verbal humor that dominates the movie is framed by Alverson’s commitment to a lovely chiaroscuro that transforms his ugly, terrifying, and morally repugnant cast into objects of beauty. Swanson lives on a boat that bobs quietly in the middle of the East River, and instead of the gentrified shot we’ve come to expect of the Manhattan skyline from a Williamsburg rooftop, Alverson’s first post-mangina image is a slightly depressed view of the new World Trade Center with silver buildings and silver water winking conspiratorially at each other on a cloudy morning. The film ends with Swanson splashing around in the Long Island Sound with a strange, small child who shrieks with delight as the unlikely pair, the boy and the man-child, is bathed in sea spray and the golden light of nostalgia. But in between these two exceptional moments of visual beauty, Swanson behaves like the consummate asshole he’s meant to be, insulting women, harassing cab drivers, disturbing worshippers in church, all the while assaulting viewers with the suggestive pudge that’s always spilling over and out of his shorts. All this bad behavior is captured by Alverson’s fine eye, which uses the play of light to contrast Swanson’s roly-poly distastefulness with the finer things around him, like the delicate cheekbones of a woman Swanson seduces and wakes up the morning after by pulling her eyelids up as she sleeps.

Watching The Comedy, it’s hard not to feel one’s ethical and aesthetic sensibilities chafe at each other. Is it right to show someone so alienating, someone so unbeautiful, inside and out, in such beautiful light? There’s no satisfying answer to that age-old dilemma, but it doesn’t really need one. What inheres in this “queasy question,” as King Lear’s Edmund calls all unanswerable asks, is the tension between the verbal reflexivity of The Comedy’s spoken humor and what Barthes calls the “never verbalized pathos” of its visual aesthetic. It’s queasy, not easy — it’s not meant to be resolved to our satisfaction.

The lack of a clean, karmic ending to the normative saga of the hipster is what makes The Comedy worth a first, second, and even a third look, preferably with someone who likes feeling uncomfortable in your company. Because, ultimately, queasiness can cut in one of two ways: you can settle an upset stomach or you can choose to self-excavate. I’m speaking metaphorically, of course, when I say that queasiness can often lead you to spew your uneasy thoughts into the ether with as much one-sided determination as the monologues that induced such queasiness in the first place. Should you choose to do so, it’s nice to have someone there to hold your hair back and say, “Please, tell me more.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Merve Emre is associate professor of English at the University of Oxford. She is the author of Paraliterary: The Making of Bad Readers in Postwar America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), The Ferrante Letters (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), and The Personality Brokers (Doubleday: New York, 2018), which was selected as one of the best books of 2018 by the New York Times, the Economist, NPR, CBC, and the Spectator. She is the editor of Once and Future Feminist (Cambridge: MIT, 2018) and a centennial edition of Mrs. Dalloway, forthcoming from Liveright.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Shopping and Fucking: “The Canyons”

Looking beyond a world of affectless, trust-funded sexual libertines.

Girls, Season 2: "It's About Time"

On the season premiere of HBO's 'Girls'

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!