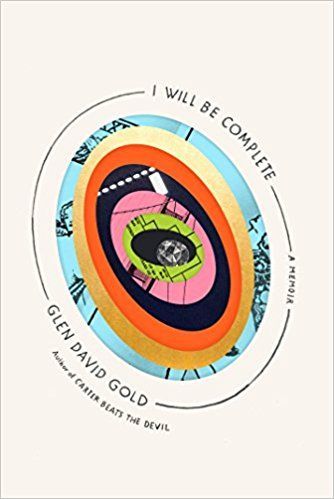

I Will Be Complete by Glen David Gold. Knopf. 496 pages.

GLEN DAVID GOLD, author of Carter Beats the Devil (2001) and Sunnyside (2009), has now released his first work of nonfiction. While Carter concerned a legendary magician and Sunnyside followed the career of Charlie Chaplin, I Will Be Complete is the tale of Gold himself, set in California in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s — from Orange County to San Francisco, westside Los Angeles to the East Bay and back. The book’s driving force is the author’s relationship with his mother; the dynamic between them compels us through the story even as it increasingly repels the son.

Glen’s mom starts off as a mystery and to some extent remains one, at least until the book’s final, tragic reveal. Initially, she’s a normal Orange County housewife, though caught between two worlds: on one side, her impoverished upbringing in England, with a schizophrenic alcoholic mother and a cold and largely absent father; on the other side, a future she longed for beyond domesticity, with a career of her own, broad-minded friends, and perhaps an element of novelty.

It’s easy to understand her alienation from Glen’s engineer father, in the second marriage for both. The elder Gold is gleefully materialistic, in the most callow and embarrassing way. When his business fails and the marriage does too, Glen’s workaholic father returns to Chicago to find a mate as wealth-obsessed as he is. In his father’s new home, Glen is patently unwelcome. Glen’s mother responds to the divorce as an adventure, beginning with a trip to San Francisco on a lark. She and Glen soon join a scene there — a neighborly menagerie of artisans, leather daddies, and holistic health workers — that is initially stimulating for them both. Glen discovers underground comics, while his mother, mingling with San Francisco notables like Herb Caen and Margo St. James, finds her life ripe with promise.

From the outset, however, we know that something is amiss. Glen’s mother has allied herself with a loud-mouthed flim-flam man; though she’s smart enough to see through him, she allows him to negotiate her divorce settlement and follows his dubious investment advice. The boyfriends who follow take what’s left of her money. One guy pawns her jewelry, likely to buy coke; she cries for him and bails him out. Dwindling reserves force them to move and Glen to give up his cat. Soon, she takes up with a broke fashionista and follows him to New York. Precocious 12-year-old Glen, whose main complaint is, “Mom, I’m plagued by feelings of unreality,” can surely take care of himself, right? His dad agrees he’ll be fine.

And so Glen muddles along in a cheerless Home Alone montage. He eats junk food, skips homework, watches B-movies, and runs late to school. He’s scared of strange noises and doesn’t sleep nights, instead roaming the hills, watching fog cloak the Bay. He knows which streets to avoid but not how to fight off the private school bullies: he’s chubby, awkward, and seemingly friendless.

This tenuous existence continues on and off for a few months until, with his parents’ approval, Glen applies to a boarding school in Ojai. Glen lacks the grades but, like Tobias Wolff before him, finds his way in, and soon he comes into his own. In the book’s funniest scene, he buys an older boy’s soul in exchange for a comic book, then sells it back for a profit. As Glen leaves for Wesleyan in Part II, his parents both move back to Southern California — his dad to raise a new family in Brentwood, and his mom to start over in San Diego, having been cleaned out and abandoned once again. She doubles down desperately on the pernicious myth that a woman’s love can redeem a man, if only she keeps on giving.

The next part of the book covers the latter half of 1983 in exhaustive detail, while we see almost none of Glen’s mother. Glen stays with his dad for the summer and then takes a term off to work in a Westwood bookstore before transferring to Berkeley. He falls for a co-worker, and this section really belongs to her, with all her dreams and ailments. They encounter celebrity bookstore patrons, and Glen braves the crowd at a punk show.

Gold has a way with one-liners, and the self-deprecating humor is gratifying. But Part II — largely a collection of droll vignettes from a teenage summer of parties, flings, and retail work — almost seems like it belongs in a different book. In the context of Gold’s bigger story, it feels like he’s cut the engine and left us to paddle. Some critics have complained that his novels can feel disjointed, aimless, and overstuffed, apt comments here as well. Beginning with this section, the book’s organization feels arbitrary rather than integral; more to the point, it could stand to lose a quarter of its length (like Gold’s novels, it weighs in at around 500 pages). The text is also riddled with abstract passages that, except for an effective metaphor involving a telescope, feel pointlessly repetitive and opaque.

The narrative regains some momentum with Part III, as the timeline picks back up and Glen’s mother reenters the picture in a significant way. (Meanwhile, his father divorces for a third time.) All three sections revolve around Glen and a female companion; in this case, it’s his late-college girlfriend (the strongest characterizations, however, are of his mom’s love interests, not his). The young lovers share a house full of friends with artistic leanings, somewhere between a clique and a community. Fulfilling a long-cherished fantasy of Glen’s, it’s a tamer version of the world his mother first joined in San Francisco, with critical theorists in place of con artists. In another sign of the times, Gold describes Berkeley as “playing the same role as it had for generations, a comfortable town for college graduates who needed a place to be kind to them.” This is when Glen gets serious about writing: he takes workshops, submits stories to journals, and bangs away at several manuscripts after graduation.

By this point, Glen’s mom has entered into a deeply co-dependent affair with a tweaker half her age, whom she commits to saving. He’s repugnant in every sense: bigoted, fanatical, and perverted in some way too awful to know. He compulsively gambles, hurts household pets, and chain-smokes for good measure. The pair are intermittently homeless. After cheating on Glen’s mom, he develops AIDS, and the whole trailer park where they’ve moved prays that he’ll die (it’s the early ’90s, so this is not an idle wish). But he needs her in a way she never thought Glen did, and she’s convinced she deserves him. Around this time, Glen starts an MFA at Irvine, where he meets now-ex-wife Alice Sebold and starts writing this volume.

The book’s advertising deceives somewhat, stressing Glen’s mother’s unconventionality, thus creating the impression that she’s some kind of hippie hedonist. In reality, she’s something all too conventional — a tortured woman who’s endured untold abuse throughout her life, not at the hands of Glen’s father but of others before and after him. It’s a credit to Gold that, even as he struggles to understand her, he paints her vividly.

Ultimately, the book asks us to consider a familiar pair of questions. First: At what point are addicts — and martyrs of all kinds — to blame for what befalls them? As Gold summarizes eloquently in his closing: “The destruction my mother has brought onto herself is so much larger than how it impacted me. My mother has very carefully, day by day, decision by decision, ruined her own life.”

Second: At what point should their loved ones cut their losses and move on in order to rescue themselves? This question is easier, because it depends on personal limits. Gold’s memoir invites the jury of readers to judge him, asserting throughout the book that he no longer loves his mom, as if making the appeal, See how hard I tried? Indeed, he’s gone above and beyond for her, so it’s easy to see how she’s drained his filial love. The two may not be fully estranged; we know she’s proud of his work, but he’s learned to keep her at several arms’ length for his peace of mind. And he’s right to: even the most generous answers to the first question don’t require loved ones’ self-abnegation. His mother is broken, but he doesn’t need to be.

It’s a troubling quandary that Glen’s father escapes condemnation, not just by being the saner parent but simply by having left first. There’s something of a double standard at play as Glen tries to make sense of his childhood. A similar bind dogs other memoirs in the dysfunctional-family subgenre, from Edward Dahlberg’s classic Because I Was Flesh (1963) to Ariel Leve’s An Abbreviated Life (2016). In cases where the mother comes out ahead in the memoirist’s estimation, it tends to be by standing with a monstrous father (as in Pat Conroy's autobiographical The Great Santini [1976]) or by choosing a disastrous stepfather (as in Tobias Wolff’s This Boy’s Life [1989]). We needn’t excuse mothers like Gold’s to call for a little more context.

Certainly, a single mom in the ’70s would have dealt with major challenges, even without an ominous family history haunting her. On top of the predators both financial and sexual, who smell vulnerability like sharks drawn to blood, Gold’s mother faced real systemic prejudices, including relegation to the pink-collar ghetto with its limited earning potential. Despite her distorted “kaleidoscope” vision, she’s pretty damn resourceful and nothing if not tenacious, albeit suicidally so. In the end, there’s one last man she’ll never let go of, and that’s the author himself.

Gold reveals early on that his mother wanted to be a writer, attempting several works of autobiographical fiction during his suburban childhood. Even many years later, when she has to write something, she does it well. In the meantime, she got into the habit of “broadcasting” her version of events, narrating her life out loud. But what if she didn’t have to? What if, instead of seeking validation from a therapist, lover, employer, friend, or son, she turned her own life into art? I’d like to read that story, written however she sees fit. She can tell it slant, or kaleidoscopically.

Finally, it’s worth noting that there’s a back door into the book for avid music fans, especially readers of Gold’s generation. In fact, the story is so packed with musical references that it virtually demands a soundtrack. To that end, I have constructed the following playlist. The tracks will all fit on a single disc, and listening enlivens the read considerably:

- “Moon River” (Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass) — This is the song Glen’s mom sings him as a kid and often reminds him about. Alpert owned Glen’s dad’s cassette company; when he withdrew his support, it failed.

- “The Arrangement” (Joni Mitchell) — Peter Charming, the story’s pivotal con man, repeatedly tells people he knows Joni Mitchell, until she herself catches him making the claim.

- “That Cat Is High” (The Manhattan Transfer) — A member of this San Francisco vocal group bonds with Glen over Marvel comics.

- “Feelin’ Alright” (Traffic) — Glen hears this psychedelic band for the first time at Thatcher, his boarding school, and it blows his mind.

- “Same Old Scene” (Roxy Music) — Glen’s classmates listen to the cynical English glam band, though they deride the New Wave style toward which the band turns.

- “Candyman” (Grateful Dead) — This San Francisco jam band is popular at Thatcher, and later among Glen’s fellow Berkeley grads.

- “No Expectations” (Earl Scruggs and Tom T. Hall) — Glen’s high school buddy Owen introduces him to the music of Scruggs, Johnny Cash, and Buck Owens, and then to punk.

- “Sex and Dying in High Society” (X) — This Los Angeles punk act is the only one Glen likes, and he meets a girlfriend at one of their record releases.

- “Pruitt Igoe” (Philip Glass) — Owen mocks Glen for loving Glass’s work; this piece is from Koyaanisqatsi (1982), then Glen’s favorite film.

- “Corona” (Minutemen) — This San Pedro band opens for the Bay Area’s Dead Kennedys at the show-turned-riot that Glen attends.

- “San Diego Serenade” (Tom Waits) — Glen’s summer love interest is a fan of this L.A. transplant; meanwhile, Glen helps his mom move to San Diego on short notice.

- “This Town” (The Go-Go’s) — This L.A. punk-turned-New Wave band blares from a car of sorority girls who try and fail to pick up Glen, mistaking him for a prostitute.

- “Theme from M*A*S*H” (Bill Evans) — One of Glen’s fellow booksellers listens exclusively to Bill Evans; Glen’s lover’s boyfriend returns to work on a M*A*S*H series spinoff, ending their affair.

- “Hero Takes a Fall” (The Bangles) — Los Angeles’s The Bangles and Three O’Clock are part of the Paisley Underground scene Glen’s Berkeley housemates revere.

- “Scorpio Rising” (10,000 Maniacs) — This band’s debut record plays at Glen’s first Berkeley party; soon, Glen gets into astrology.

- “Cuyahoga” (R.E.M.) — Glen and his college girlfriend use this song to invoke a psychic connection they believe they share.

- Concerto in D Major for Lute and Strings, RV 93: II. Largo (Vivaldi) — Glen decides, while rolling on ecstasy (or possibly DMT), that he heard this longtime favorite piece in a previous life.

- “When Tomorrow Comes” (Eurythmics) — Glen’s college girlfriend uses this song to promise she’ll always stay with him.

- “Stop” (Jane’s Addiction) — After she leaves him, he hears this L.A. band at a party while tripping.

- “Trompe le Monde” (The Pixies) — When Glen meets his last girlfriend before Sebold, he is deep into the Pixies, the gym, and his motorbike; their final album marks a turning point in the story.

¤

LARB Contributor

Bonnie Johnson is at work on An Atlas of Utopia, an essay collection about intentional communities.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Being There

Peter Grandbois on why we should read David McGlynn's "One Day You’ll Thank Me: Lessons from an Unexpected Fatherhood."

Coming Home from Irony: An Interview with Percival Everett, Author of “So Much Blue”

Yogita Goyal talks to Percival Everett about appropriation, "Get Out," Los Angeles, and his new novel.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!