The Problem Belongs to Every Last Person: On Matt Bell’s “Appleseed”

Matt Bell’s “Appleseed” explores a world led by Silicon Valley types for whom saving the planet is just another business venture.

By Morgan FordeJune 26, 2021

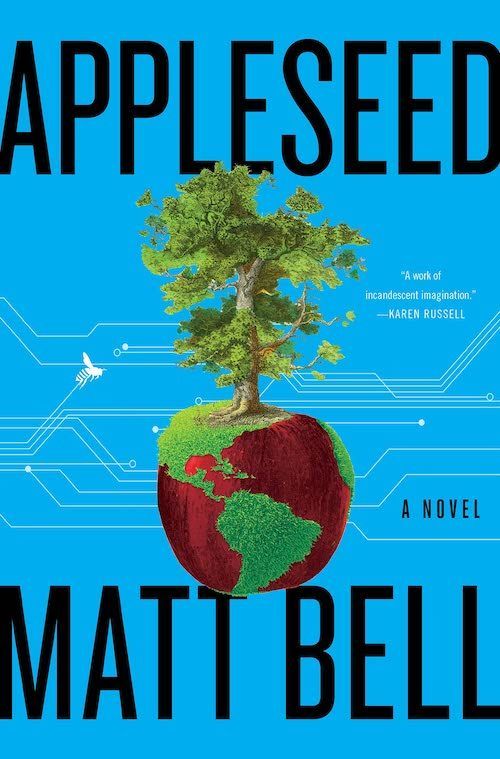

Appleseed by Matt Bell. Custom House. 480 pages.

I FIRST BECAME aware of the United Nations’s Agenda 21 proposal from a pamphlet my grandfather handed me when I was around 10 years old. The sky-blue booklet, which I still have in a storage box somewhere (a crude memento after his passing last year), was produced as part of a conspiracy theorist movement that saw the UN’s proposal for equitable global trade and sustainable urban development as a dystopian campaign for a socialist one-world-order that would empty rural lands and forcibly condense people into cities. It’s been a while since Agenda 21’s debut in 1992, but the UN proposal still garners attention within ecological movements, urban studies programs, conspiracy fantasies, and science fictions. Recently, books such as E. O. Wilson’s Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life and Tony Hiss’s Rescuing the Planet: Protecting Half the Land to Heal the Earth have advanced visions inspiring the Half-Earth movement, which proposes that 50 percent of global lands and waterways should be turned into conservation areas — an ecological prospect that has doubtlessly sent Agenda 21 truthers into a spiral.

Whereas the government-wary libertarian may balk at a Half-Earth proposal, Matt Bell’s latest novel, Appleseed (Custom House, July 2021), takes an approach that seems eerily more plausible amid the rising influence of Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Elon Musk, and any number of neoliberal “lone genius” types for whom saving the planet is just another business venture — an industry ripe for disruption and monopolization.

Appleseed plays on the dystopian climate disaster genre, deftly weaving threads from Greek mythology, magical realism, and America’s settler-colonial folklore to create the parallel universe its characters inhabit. True to its title, the book opens on two brothers, one human and one faun, venturing across the unsettled Midwestern frontier planting apple orchards. Chapman, the faun, harbors a secret desire to plant and harvest the perfect apple, one that will make him human and end his agonizing struggle between embracing his horned wildness and his desire to live a normal life alongside his brother. His story forms the “past” portion of the novel’s tri-temporal triptych structure, wherein each chapter follows characters centuries apart from each other in a recursive past/present/future cycle.

The plot’s central narrative (a term used loosely) takes place around 2070 after climate devastation has forced the creation of a “Sacrifice Zone” across the western and central United States. Choosing between the consolidation of the population or widespread urban collapse, the government has evacuated cities and rural communities, pushing them toward the East Coast and life on the megacorporation Earth Trust’s Volunteer Agricultural Communities (VACs).

Not everyone has relocated willingly. Some stay behind to brave the heat and drought, preferring a Mad Max–adjacent freedom. Others detonate hydroelectric dams, tear up roads, and destroy infrastructure in a bid to re-wild the Sacrifice Zone and prevent Earth Trust’s re-incursion in the federal government’s absence. John, the “present-day” character, falls in the latter group. Perhaps a millennial’s grandchild, he grew up in Ohio and saw crippling drought and the extinction of the world’s honeybees, tragedies that pushed him to co-found Earth Trust with his childhood friend Eury. What begins as a garage start-up, however, quickly becomes an agro-industrial corporation turned independent global techno-state (think Amazon meets Microsoft meets a public-private infrastructure project on steroids).

While John wants to design nano-bees to pollinate and revive the nation’s remaining plant species, Eury unleashes grander ambitions. After John leaves the company to dwell in the Sacrifice Zone, Eury launches the VACs where specially designed crops (among them genetically modified apples), algorithmic efficiency, and social engineering combine. The arrangement enables Earth Trust to feed whole countries while housing and employing their climate refugees as Volunteers.

Despite global efforts, or a potent lack thereof, the climate only continues to inch closer to complete ecological disaster. While some of the world’s elite plan for hypothetical evacuations to Mars, Eury announces plans to turn back the clock and restore Earth’s lost species and habitats with one final moonshot project. However, her gift to humanity comes at a high price, one that John and a group of resistance fighters plan to prevent the world from paying.

Meanwhile, in Appleseed’s third narrative, a thousand years in the future, a 3D-printed creature named “C” descends from a broken-down science vessel into the depths of a glacier. He scavenges the remnants of a civilization that came before, long since buried under a new ice age. At the bottom of a crevasse, C finds a twisted wreck of a tree, a relic that may hold the key to what caused humanity’s demise. In his haste to return to his ship, he suffers a climbing accident, which forces him to throw himself — and the tree sample — into the ship’s recycler. Moments later, C is reprinted and reimbued with the memories of generations of clones that came before him. But each C is a little different, cobbled together from core biological elements and synthetic replacements harvested from the ship. With the injection of the tree, however, this C becomes something else entirely. His search for the tree’s origin instead becomes a search for humanity, or what’s become of it.

Unpredictable to the last page, Appleseed ties these disparate narratives together with a rich network of symbolism and sharp prose. While there are tensely written action scenes befitting a sci-fi thriller, at the book’s core is a burning ethical question that wavers on the knife-edge of climate optimism and fatalism: Faced with the end of the world, would you bet on humanity to finally come together and avert disaster? Or one woman, one company, with a vision and the means to guarantee the outcome?

To quote the book, “The problem is bigger than any one person, any one company or government: the problem belongs to every last person; until it’s solved everyone remains complicit, even if they resist.” Bell tackles this aphorism from the novel’s opening in the age of settler-colonial expansion across the United States. Chapman’s quasi-magical and spiritual connection to nature, and his only partial humanness, opens a window into the “original sin” committed by successive generations of settlers that worked their way across the continent exploiting nature for their survival. There is beauty in the planting of orchards, yet a profound irony in the streams Chapman and his brother divert and the trees they cut down to make space for them. Thus, nature gives and gives over millennia until its exhausted collapse forces mankind back the way it came in a race against extinction.

Appleseed is propelled by the strength of its ideas rather than its specific characters or exotic worldbuilding. There are nods to Iain M. Banks and Ursula K. Le Guin, which might make the reader feel as though they’re watching an elaborate thought experiment untangle itself. The characters have lives of their own insomuch as they are tools to solve that greater puzzle. As such, the book occasionally breaks the fourth wall, veering away from the temporal plots into passages such as the one quoted above where the narrator speaks directly to the reader about their current and future complicity in the events about to occur. In this way, Bell pulls readers back and forth between seeing Eury and Earth Trust’s enormous power as a villainous force to be fought, and the only means of survival in a world where governments are ineffectual and unsustainable resource consumption continues unabated. Moments such as these, and more ethereal scenes where Chapman is chased by three time-bending spirits in the Ohio woods, pull Appleseed out of the sci-fi genre and into something more — a cerebral folktale all its own.

Because the novel’s present-day timeline is so close to our own, the alternate world Bell creates feels jarringly prescient. Bill Gates is already the largest private owner of farmland in the United States and has plans to create a new city in the Arizona desert. Nevada is considering a law that would allow corporations to build and manage legally autonomous cities, and Elon Musk has long had his sights on Mars. Couple these realities with the long-standing American belief in the power of companies to innovate faster and further than state actors and it’s not hard to imagine a future where the fight against climate change isn’t waged against multinational corporations but is co-opted by them.

Appleseed is not your typical sci-fi novel in the same way the 2016 film Arrival is less about an alien invasion and more about theories of linguistics-driven perception. So, while readers expecting a gritty climate dystopia, or a one-world-order, might be disoriented by Appleseed’s bucolic opening chapter about an apple-obsessed 18th-century faun, they’re in for something incredibly unique and equally gripping.

¤

Morgan Forde is a freelance writer and editor based in Washington, DC.

LARB Contributor

Morgan Forde is a freelance writer and editor based in Washington, DC.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Three Books About a Better World

Kim Stanley Robinson, Yanis Varoufakis, and Carl Neville have all released utopian novels in 2020, but is there value in speculating about a...

Odd Couples, Carbon Coins, and Narrative Scopes: An Interview with Kim Stanley Robinson

Kim Stanley Robinson and Everett Hamner discuss “The Ministry for the Future,” ecological defense, gender equity, economic policy, and ecoreligion.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!