The Present Waver: On “Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts”

Jordan Alexander Stein reviews "Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts" by Rebecca Hall and illustrated by Hugo Martínez.

By Jordan Alexander SteinSeptember 17, 2021

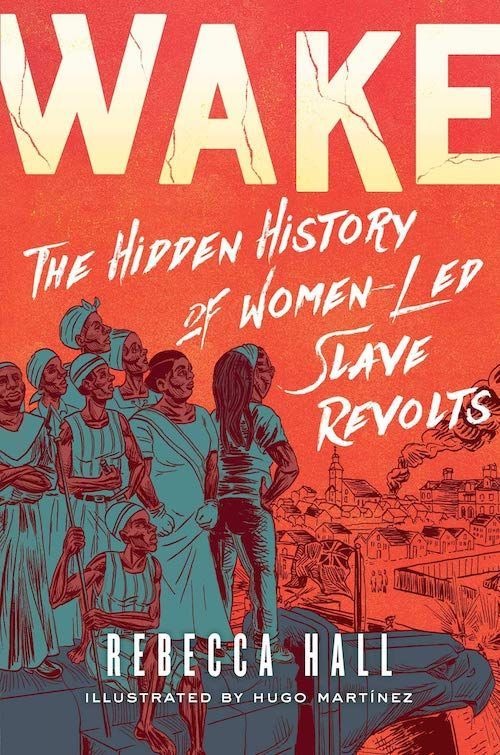

Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts by Rebecca Hall. Simon & Schuster. 208 pages.

IN THE SUMMER of 1987, the academic journal Diacritics published an essay by Hortense J. Spillers titled “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book.” Marshalling its author’s considerable interdisciplinary chops, the essay drew a line between the racist laws applied to Black families under chattel slavery and the racist assumptions brought to bear on Black families in the postwar United States. Spillers’s essay, its evidence, its argument, and its extraordinarily generativity defies easy summary — despite, or perhaps due to, a citation count well into the thousands. The essay traced the boundary of what became an entire field of study situated in the overlap of critical theory, African and African American studies, feminist inquiry, textual analysis, and archival research. That field is now usually called Black Studies.

Almost 35 years later, there is perhaps only one single sentence in Spillers’s 20 dense pages that doesn’t hold up — a transitional aside where she observes, “The conditions of ‘Middle Passage’ are among the most incredible narratives available to the student, as it remains not easily imaginable.” Meanwhile, the reason this sentence may not hold up owes to the publication, later in 1987, of Beloved, Toni Morrison’s extraordinary historical novel. Featuring a self-emancipated woman whose present is confounded by a past in which she murdered her baby girl rather than allow her to be remanded to slavery, Beloved holds at its narrative center a poetic chapter where voices of the enslaved dead and voices of the enslaved in Middle Passage transit speak across history’s gaps.

A mere three months after “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” Beloved made the Middle Passage imaginable, though certainly not easily so. One way of understanding the convergence of these works would be to say that Morrison saw very much the same gaps that Spillers diagnosed and lent the full force of her artistic powers to filling them. Worth lingering over, however, is the way that fiction emerged as the first successful candidate to flesh out what appeared otherwise lost to history.

If those of us who make an intellectual home in Black Studies do our work, as above, in the overlap of critical theory, African and African American studies, feminist inquiry, textual analysis, and archival research, we may labor credibly without attending to these components equally. Apart from scholarship undertaken by professional historians writing in conversation with Black Studies, it’s often the “archival research” piece that gets the short straw. One reason, perhaps, as the examples of Spillers and Morrison already suggest, is that one can make important historical interventions with theory or fiction. Another reason may have to do with the white supremacist structures that keep history’s records incomplete, uneven, and with often deliberate disregard for Black life. The history of the Middle Passage can be written, but the researcher who undertakes this task must display as much ingenuity and creativity in looking for sources and stories as would any novelist.

And so, many practitioners of Black Studies make historical claims by leaning on something other than archives proper — on fiction, as we’ve seen, but also on theory or memoir or poetry — because it’s often more possible to see something real than to prove it empirically; because the incompleteness of a proof is the evidence of something in its own right; because proof is a social standard and as such it’s shaped by the same racist and gendered economies as the rest of our society. Some things that are nearly impossible to prove still need to be known. To this problem, the creativity of Black Studies provides an often urgent, elegant solution. And to this solution, with Rebecca Hall’s graphic novel Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts, add comics.

¤

Wake tells the story of Rebecca, a tenants’ rights attorney turned history PhD student, sorting through archives and municipal records in New York and London between 1999 and 2002. She’s haunted by the history of slavery and sees its evidence everywhere — human horrors displaced onto sanitized structures, plantation violence transformed into English tea and sugar, neo-classical facades and shining glass towers built on unconsecrated graves scattered across the Atlantic trading capitals through which she walks. Like these cities themselves, their archives obscure the stories of so many enslaved people whose extracted labor — whose literal blood, sweat, and tears — leaves only the most occasional traces in the historical record, and only if you know where to look. The premise of Wake, then, is that the evidence of the history of slavery lives everywhere except the archives whose responsibility it is, theoretically at least, to document that history.

The evidence of enslaved women — women warriors, as Rebecca lovingly designates them — is even harder for her to put her hands on. Doubly obscured through centuries of racism and sexism, enslaved women were underestimated both by enslavers and, maddeningly, by many modern historians. Contemporary with Rebecca’s research, a quantitative analysis in the 1990s found a high correlation between revolts on slave ships and ships with enslaved women as “cargo,” yet the official write-up erased these women’s agencies, declaring their presence on the scene of uprisings as counterintuitive, a statistical fluke.

But Rebecca’s challenge, and the work of Wake, is not just to reinterpret the data. It’s also to bring the data to life, to tell the stories of the flesh-and-blood people whose existences have been reduced to lines in a ledger. It’s to revive and commune with the dead. To do its work, across a preface and 10 chapters, Wake alternates between the present tense of Rebecca’s research and the reconstructed dramatizations of women-led slave revolts in New York in 1712, in Newton (now Elmhurst, Queens) in 1708, and in the Kingdom of Dahomey (now Benin in western Africa) in 1769. These alternating sections of memoir and historical fiction are held together by a cohesive and reflexive narrative, mirrored in illustrator Hugo Martínez’s delicate and sinewy lines, which move and angle to suggest the busy-ness and frisson of a world that always exceeds itself.

Wake does not announce itself as a work of Black Studies, yet the conceptual frame and narrative modulations would seem to locate it easily within the critical and aesthetic territory of this field. The title does not explicitly allude to Christina Sharpe’s influential In The Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016), so much as it evokes the same tropes, implying a conversation if not a citation. Likewise, the narrative does not mention the practice of “critical fabulation” that Saidiya Hartman put forward in “Venus in Two Acts” (2008), yet this kind of informed extrapolation from too-thin archival evidence is very much Wake’s method. Like many works in Black Studies, Wake is committed to envisioning the things we know to be true, but that have, by design, been made difficult to prove.

Toggling between the present and the historical past, between the paucity of recorded details and the undeniability of historical events, Wake turns a rebuttal against the designed difficulty of empirical proof into the grounds for its own story. It’s this meta turn that fascinates, for it so brilliantly makes use of the positionality of the character Rebecca. Her actions, her embodiment, her movement through the world, all dramatize the complexities of being a Black woman in a white supremacist patriarchy. In one scene, overcome with details of violence and misogynoir she finds at the New-York Historical Society, Rebecca stumbles out onto Central Park West and has some difficulty getting a cab. In another, standing in front of a judge in her former life as a Bay Area attorney, she’s mistaken for the defendant. Elsewhere, running after a needle in a haystack at the Queens County Criminal Court, she can’t get into the building because no one believes she’s a historian. At the archives of the Houses of Parliament in London, she’s followed by a male security guard all the way inside the women’s bathroom.

Wake’s memoir sections rarely dilate on these indignities and violences, and tend rather to play them out with little comment. These sections rely instead on the visual aspect of their storytelling to show us what they don’t tell us. The result is that we begin to know something without having been given any words we can cite to prove, or even just point to, where our knowledge comes from. We learn how archives can be violent places — scenes of erasure, of neglect, of lives deemed beneath the dignity of record — and how some version of the violence of the archives is enacted on the researcher who comes to work in them. We learn how the historian’s pursuit of the record is a record in itself.

The memoir sections, in other words, don’t tell us what it’s like to be Rebecca, so much as they set the intellectual and personal aspects of her project in juxtaposition. The distribution of the life to images and the work to words makes powerful use of the comics medium, inviting the reader to sit with epistemological as well as formal connections. The visual world of this text, the comics that illustrate but more often propel the story, does something that work in Black Studies also does, though in a medium the field has rarely engaged. Wake accomplishes what the best work in Black Studies aims to do: not just to teach us something new, but to teach us how the very shape of our knowledge could be different. Or, as Hall paraphrases from Beloved, haunting is what makes the present waver.

¤

Sandwiched into a middle chapter of Wake is one very unexpected fact: Rebecca is the granddaughter of slaves. Only two generations removed. Her grandmother, born into slavery, apparently gave birth to Rebecca’s father at a relatively advanced age, and he in turn sired a daughter when he was fairly old. For understandable reasons, this biographical detail matters hugely to Rebecca. But as Wake contracts the 158 years since the Emancipation Proclamation into the space of three generations, historical time becomes human time in a way that for most readers will be difficult to relate to.

Narratively speaking, the point of routing a history through the person telling it is to give us readers a point of identification — Rebecca’s discoveries become our discoveries, Rebecca’s experiences reflect and amplify aspects of our own. And while this character and her experiences are in these ways relatable, her grandmother’s enslavement points, too, to the fact that this character is also entirely specific, unusual, irreducible.

Such specificity suggests that the relationship between the present tense of the story and the past it seeks to uncover isn’t flatly causal. This isn’t simply a narrative told out of chronological order — there are no Citizen Kane–esque precipitating circumstance introduced to the reader in flashback. Rather, the facts of history emerge as distinct stories whose chief point of connection is that none of them, for nearly identical reasons across the span of three centuries, were meant to be told. Given this specificity and how Wake makes use of it, its first-person perspective can’t merely be called a device. And in not being so, it stands apart from much contemporary writing — in Black Studies and beyond — that relies on personal perspective.

A whole lot of ink has been spilled over the rise, in the past decade or so, of what’s often identified to be a specific genre of autobiographical writing: “autofiction.” Distinct from autobiography, autofiction is creative writing; but distinct from fiction, autofiction is fairly close to a true story. Wake’s project is arguably related to this trend, but the more interesting possibility it raises is that perhaps autofiction is simply borrowing something that Black Studies, its inheritors, and even its progenitors, have long been pioneering. As Wahneema Lubiano argued 30 years ago, in relation to a different reflexive trend in critical writing, what’s new to the academy isn’t at all new to the Black cultural criticism that takes place, as she put it, “off campus.”

The last chapter of Wake meditates on how to heal trauma, which might not be the obvious concern for historical scholarship and might instead seem like it belongs to the memoir part of the story, but the opposite is the case. It’s not possible to study the past without also bringing the ways the past has shaped us and our present to bear on that study. Wake wonderfully turns what might seem like a limitation or a lack of objectivity toward acts of learning and creating. It pushes past the limits of what’s possible, to tell us a story that wasn’t but now can be.

¤

Jordan Alexander Stein teaches at Fordham University and tweets @steinjordan.

LARB Contributor

Jordan Alexander Stein teaches in the English Department at Fordham University. He is co-editor of Early African American Print Culture (U Penn Press, 2012) and a contributing writer at Avidly.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Archival Futures: The Archive as a Place and the Place of the Archive

Rethinking the research archive in an age of pandemics and digitization.

Regard for One Another: A Conversation Between Rizvana Bradley and Saidiya Hartman

Rizvana Bradley and Saidiya Hartman talk about Hartman's new book, "Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!