The Machinery of Death

Stephen Rohde discusses the possible elimination of the death penalty.

By Stephen RohdeOctober 15, 2016

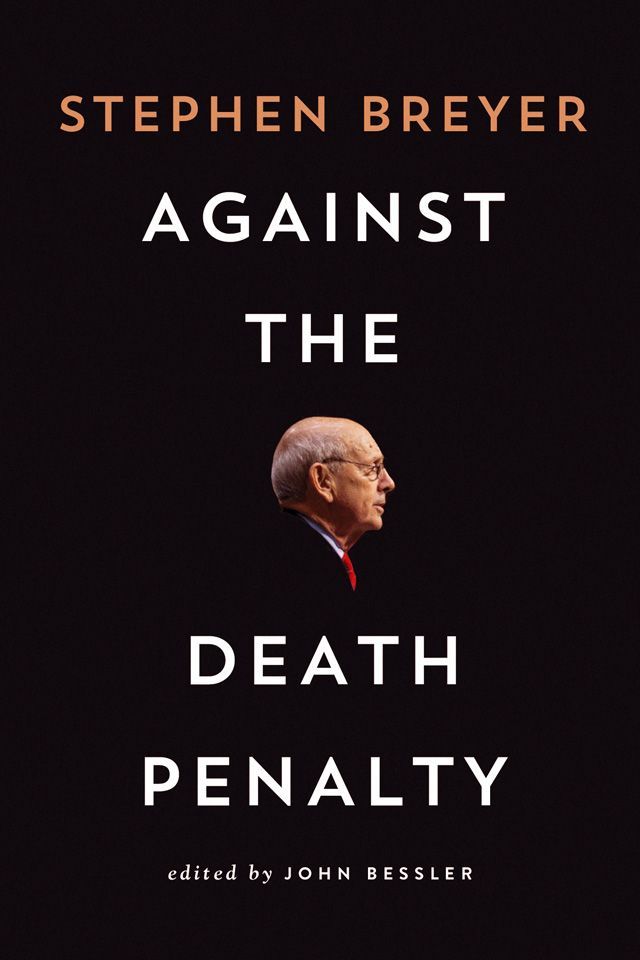

Against the Death Penalty by John D. Bessler and Stephen Breyer. Brookings Institution Press. 176 pages.

Courting Death by Carol S. Steiker and Jordan M. Steiker. Belknap Press. 400 pages.

LAST FEBRUARY, two pivotal events occurred regarding the death penalty in the United States. On February 13, US Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, a staunch defender of the death penalty, died. Ten days earlier, Brandon Jones also died. He became the 294th person to die in a botched execution in our country.

After spending 24 minutes unsuccessfully trying to insert an IV into Jones’s left arm, executioners spent eight minutes trying to insert it into his right. When that failed, they again tried his left, and failed once more. A physician (in violation of several codes of medical ethics) then spent 13 minutes inserting and stitching the IV near Jones’s groin. Six minutes later, Jones’s eyes popped open. He was 72 years old at the time of his execution.

Two new books on the death penalty predict that inmates like Brandon Jones may soon never face the prospect of state killing in the United States.

In Courting Death: The Supreme Court and Capital Punishment, Carol S. Steiker, Henry J. Friendly Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, and her brother, Jordan M. Steiker, Judge Robert M. Parker Endowed Chair in Law at the University of Texas School of Law, provide a clear and comprehensive look at the 40-year modern history of capital punishment in the United States since its reinstatement in 1976. Their blunt conclusion is that the Supreme Court “has regulated the death penalty to death” and that “for the first time since the late 1960s, nationwide abolition seems achievable in the foreseeable future.”

In Supreme Court history, a few dissenting opinions have eventually won over a majority of the court. With the death of Justice Scalia, Justice Stephen Breyer’s powerful dissenting opinion on the death penalty in Glossip v. Gross (2015) — joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg — may become one of those cases. In his dissent, Justice Breyer presents compelling reasons why capital punishment violates the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on “cruel and unusual punishment.” Depending on the court’s makeup after the 2016 election, Breyer’s dissent could become the law of the land.

This potentially historic dissent serves as the focus of John D. Bessler’s short and insightful book, Against the Death Penalty. A law professor at the University of Baltimore School of Law and adjunct professor at the Georgetown University Law Center, Bessler provides a comprehensive 70-page introduction, briefly tracing the evolution of capital punishment over the last 250 years, in addition to including the full text of Breyer’s dissent. It is a timely and well-informed work that makes a convincing case for abolishing state killing.

Together, these two books serve as an ideal graduate course in one of the most contentious issues in American life. Courting Death provides an excellent survey of the history of capital punishment and the prospects of abolition, while Against the Death Penalty zeroes in on the analysis of a single Justice (two, counting Justice Ginsberg), which could chart the legal roadmap to ending this irreversible form of criminal punishment.

Examining the fatal flaws in the capital punishment system could not be more timely. On November 8, 2016, the voters of California will decide the outcome of Proposition 62, which would replace the death penalty with life in prison without the possibility of parole, and according to the independent Legislative Analyst, save the state $150,000 annually. In 2012, a similar ballot measure lost by only four percent.

With almost 750 human beings on California’s death row (the largest in the United States, with 25 percent of all people waiting to be executed in the US), repealing the death penalty by a vote of the people would not only save those lives (and those of untold men and women in the future), but would also help establish the “national consensus” to achieve a Supreme Court ruling declaring the death penalty unconstitutional nationwide.

¤

The Steikers, who clerked for Justice Thurgood Marshall in 1987 and 1989, respectively, and have collaborated on scholarly, litigation, and law reform projects addressing the death penalty, point out that beginning in 1976, the Court “embarked on an extensive — and ultimately failed — effort to reform and rationalize the practice of capital punishment in the United States through top-down, constitutional regulation.” While all other Western democracies have abolished it,

what is truly unique about the American death penalty experience is that the United States has attempted to find a middle position between repealing and retaining capital punishment — by subjecting it to intensive judicial oversight under the federal constitution.

The authors convincingly demonstrate that the “Court’s attempt to square the death penalty with constitutional guarantees demonstrates both the power and failings of the Constitution by showing how judges have struggled, often unsuccessfully, to give it meaning in the most macabre circumstances.”

One of the startling facts to emerge is that while seven Supreme Court justices (Brennan, Marshall, Powell, Blackmun, Stevens, Breyer, and Ginsburg) have indicated that they think capital punishment should be ruled categorically unconstitutional, and several have renounced their previous rulings upholding capital punishment, no justice has ever moved in the opposite direction from questioning the death penalty to upholding it.

The Steikers explain technical legal issues with such clarity that their book is highly accessible to lawyer and layperson alike. By marshaling the case law and commentary, they make a strong argument that a

doctrinal blueprint is available in the Court’s proportionality jurisprudence [based on the Eighth Amendment], and current conditions on the ground may provide the necessary building blocks for an enduring constitutional edifice rejecting the death penalty once and for all.

¤

Courting Death and Against the Death Penalty intersect nicely when it comes to the “building blocks” articulated in Justice Breyer’s dissent in Glossip. As Bessler sees it, Breyer’s dissent “may represent a pivotal turning point in America’s ongoing death penalty debate. The number of death sentences and executions has already dwindled, and the nation may be at a tipping point as regards the use of capital punishment.” This trajectory could accelerate if in November, the people of California, which houses the most death row inmates in the United States, pass Proposition 62, the Justice That Works Act.

Bessler traces the movement to end capital punishment back to Italian philosopher Cesare Beccaria, whose seminal work Dei delitti e delle pene (1764) was translated into English in 1767 as On Crimes and Punishments. It was read by George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams would passionately quote it while representing British soldiers accused of murder following the 1770 Boston Massacre.

In this period, execution was the punishment for a wide array of crimes including idolatry, witchcraft, blasphemy, murder, manslaughter, poisoning, bestiality, sodomy, adultery, man-stealing, false witness in capital cases, conspiracy, and rebellion. Beccaria and his followers argued for proportionality — that the punishment fit the crime — and that no punishment be inflicted unless absolutely necessary (i.e., when no alternatives exist).

By the 1820s, toward the end of his life, Jefferson observed that “Beccaria and other writers on crimes and punishment had satisfied the reasonable world of the unrightfulness and inefficacy of the punishment of crimes by death.” Contrary to Justice Scalia’s view that the constitutionality of the death penalty was for all time dictated by the Constitution as ratified in 1788, as early as 1885, the Court was judging whether forms of punishment were “infamous” and thereby unlawful, by evolving standards and norms. “What punishments shall be considered as infamous may be affected by the changes of public opinion from one age to another.” “In former times,” the Court noted, “being put in the stocks was not considered as necessarily infamous.” “But at the present day,” the Court observed, “either stocks or whipping might be thought an infamous punishment.”

In 1910, in Weems v. United States, the Court continued to assess the constitutionality of a particular punishment by whether it is “cruel and unusual” and “repugnant to the Bill of Rights,” observing that “crime is repressed by penalties of just, not tormenting, severity.”

The modern test which prevails today in determining whether a punishment is “cruel and unusual” in violation of the Eighth Amendment was articulated in 1958 in Trop v. Dulles. In a ruling which has never been reversed, despite the strenuous efforts of Justice Scalia, the Court declared that the Eighth Amendment would be interpreted based on “evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.”

Under that standard, the Court has steadily struck down the death penalty for non-capital crimes, juvenile offenders, and the intellectually disabled. It was against all of this history that Justice Breyer set about offering his most comprehensive views on capital punishment in his dissent.

Breyer began by pointing out that in 1976, the Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty under state statutes that attempted to set forth safeguards to ensure the penalty would be applied reliably and not arbitrarily. But Breyer found that the “circumstances and the evidence of the death penalty’s application have changed radically since then.”

The court thought that the constitutional infirmities in the death penalty could be healed. However, according to Breyer, almost “40 years of studies, surveys, and experience strongly indicate […] this effort has failed.” “Today’s administration of the death penalty,” Breyer wrote,

involves three fundamental constitutional defects: (1) serious unreliability, (2) arbitrariness in application, and (3) unconscionably long delays that undermine the death penalty’s penological purpose. Perhaps as a result, (4) most places within the United States have abandoned its use.

Cruel: Unreliability. Breyer found “increasing evidence” that the death penalty lacks reliability. Researchers “have found convincing evidence that in the past three decades, innocent people have been executed.” Breyer cites the shameful examples of Carlos DeLuna, Cameron Todd Willingham, Joe Arridy, and William Jackson Marion. As of 2002, there was evidence of approximately 60 exonerations in capital cases. Since then, the number of exonerations in capital cases has risen to 115 and may be as high as 154. In 2014, six death row inmates were exonerated based on actual innocence. All had been imprisoned for over 30 years.

When one includes instances in which courts failed to follow legally required procedures, the numbers soar. Between 1973 and 1995, courts found prejudicial errors in an astounding 68 percent of the capital cases. For Breyer, the research suggests “there are too many instances in which courts sentence defendants to death without complying with the necessary procedures; and they suggest that, in a significant number of cases, the death sentence is imposed on a person who did not commit the crime.”

Cruel: Arbitrariness. As Breyer puts it, the “arbitrary imposition of punishment is the antithesis of the rule of law.” In 1976, the Supreme Court acknowledged that the death penalty is unconstitutional if “inflicted in an arbitrary and capricious manner.” Despite the Court’s hope for fair administration of the death penalty, Breyer concludes it has become “increasingly clear that the death penalty is imposed arbitrarily, i.e., without the ‘reasonable consistency’ legally necessary to reconcile its use with the Constitution’s commands.”

Breyer cites various studies and concludes that

whether one looks at research indicating that irrelevant or improper factors — such as race, gender, local geography, and resources — do significantly determine who receives the death penalty, or whether one looks at research indicating that proper factors — such as “egregiousness” — do not determine who receives the death penalty, the legal conclusion must be the same: The research strongly suggests that the death penalty is imposed arbitrarily.

Breyer concludes that the “imposition and implementation of the death penalty seems capricious, random, indeed, arbitrary.”

Cruel: Excessive Delays. Breyer found that the problems of reliability and unfairness lead to a third independent constitutional problem: excessively long periods of time that individuals typically spend on death row. In 2014, 35 individuals were executed. Those inmates spent an average of 18 years on death row. At present rates it would take more than 75 years to carry out the death sentences of the 3,000 inmates on death row; thus, the average person on death row would spend an additional 37.5 years there before being executed.

These lengthy delays create two special constitutional difficulties. First, a lengthy delay in and of itself is especially cruel because it “subjects death row inmates to decades of especially severe, dehumanizing conditions of confinement.” Second, lengthy delay undermines the death penalty’s penological rationale.

Breyer explained that the death penalty’s penological rationale rests almost exclusively upon deterrence and retribution. But Breyer asks: Does it still seem likely that the death penalty has a significant deterrent effect? He considers what actually happened to the 183 inmates sentenced to death in 1978. As of 2013, 38 (or 21 percent) had been executed; but 132 (or 72 percent) had had their convictions or sentences overturned or commuted; and seven (or four percent) had died of other causes. Six (or three percent) remained on death row. Of the 8,466 inmates under a death sentence at some point between 1973 and 2013, 16 percent were executed, but 42 percent had their convictions or sentences overturned or commuted, and six percent died by other causes; the remainder (35 percent) are still on death row.

To speed up executions, Breyer asks which constitutional protections are we willing to eliminate. He poses the dilemma:

A death penalty system that seeks procedural fairness and reliability brings with it delays that severely aggravate the cruelty of capital punishment and significantly undermine the rationale for imposing a sentence of death in the first place. But a death penalty system that minimizes delays would undermine the legal system’s efforts to secure reliability and procedural fairness.

Breyer is clear. “We cannot have both. And that simple fact […] strongly supports the claim that the death penalty violates the Eighth Amendment.”

Unusual: Decline in Use. The Eighth Amendment forbids punishments that are cruel and unusual. Breyer points out that between 1986 and 1999, 286 persons on average were sentenced to death each year. But approximately 15 years ago, the numbers began to decline. In 1999, 98 people were executed. Last year, just 73 persons were sentenced to death and 35 were executed. The number of death penalty states has fallen, too. In 1972, the death penalty was lawful in 41 states. As of today, 19 states and the District of Columbia have abolished the death penalty. In 11 other states where the death penalty is on the books, no execution has taken place in over eight years. Of the 20 states that have conducted at least one execution in the past eight years, nine have conducted fewer than five in that time, making an execution in those states a fairly rare event.

That leaves 11 states in which it is fair to say that capital punishment is not “unusual.” And just three (Texas, Missouri, and Florida) accounted for 80 percent of executions nationwide (28 of the 35) in 2014. Indeed, last year, only seven states conducted an execution. In other words, in 43 States, no one was executed. If we ask how many Americans live in a state that at least occasionally carries out an execution (at least one within the prior three years), the answer two decades ago was 60 to 70 percent. Today, it’s 33 percent.

Breyer concludes that the

lack of reliability, the arbitrary application of a serious and irreversible punishment, individual suffering caused by long delays, and lack of penological purpose are quintessentially judicial matters. They concern the infliction — indeed the unfair, cruel and unusual infliction — of a serious punishment upon an individual.

Consequently, the Supreme Court is “left with a judicial responsibility,” and it has made clear that “the Constitution contemplates that in the end our own judgment will be brought to bear on the question of the acceptability of the death penalty under the Eighth Amendment.”

Against the Death Penalty, in the hands of an astute Supreme Court justice and an accomplished capital punishment scholar, provides an excellent opportunity for lawyer and layman alike to examine one of today’s most pressing questions of criminal justice. Can a society devoted to equal justice for all, applying “evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society,” continue to engage in state killing? Can such a society tolerate the risk of executing innocent people? Can such a society execute those who are without a doubt guilty (if such certainty exists), at the risk of torturing them as Brandon Jones was tortured earlier this year?

In a 1994 dissent in Callins v. Collins, Breyer’s immediate predecessor, Justice Harry Blackmun, wrote:

From this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death. For more than 20 years I have endeavored — indeed, I have struggled — along with a majority of this Court, to develop procedural and substantive rules that would lend more than the mere appearance of fairness to the death penalty endeavor. Rather than continue to coddle the Court’s delusion that the desired level of fairness has been achieved and the need for regulation eviscerated, I feel morally and intellectually obligated simply to concede that the death penalty experiment has failed.

For the reasons compellingly presented in Courting Death and Against the Death Penalty, in courtrooms and voting booths, judges and voters have the power to stop tinkering with the machinery of death. In California, by passing Proposition 62, the people living in the state with the largest population of death row inmates can end the death penalty experiment once and for all. This would send the powerful message across the United States and indeed around the world, that as the arc of history bends toward justice, state killing has no place in civilized society.

¤

Stephen Rohde is a constitutional lawyer, lecturer, writer, and political activist.

LARB Contributor

Stephen Rohde is a writer, lecturer, and political activist. For almost 50 years, he practiced civil rights, civil liberties, and intellectual property law. He is a past chair of the ACLU Foundation of Southern California and past National Chair of Bend the Arc, a Jewish Partnership for Justice. He is a founder and current chair of Interfaith Communities United for Justice and Peace, member of the Board of Directors of Death Penalty Focus, and a member of the Black Jewish Justice Alliance. Rohde is the author of American Words of Freedom and Freedom of Assembly (part of the American Rights series), and numerous articles and book reviews on civil liberties and constitutional history for Los Angeles Review of Books, American Prospect, Los Angeles Times, Ms. Magazine, Los Angeles Lawyer, Truth Out, LA Progressive, Variety, and other publications. He is also co-author of Foundations of Freedom, published by the Constitutional Rights Foundation. Rohde received Bend the Arc’s “Pursuit of Justice” Award, and his work has been recognized by the ACLU and American Bar Association. Rohde received his BA degree in political science from Northwestern University and his JD degree from Columbia Law School.

LARB Staff Recommendations

First and Last, the First Amendment

Stephen Rohde’s reflection on his career as an LA civil rights lawyer, particularly regarding the First Amendment.

A Stronger Constitution: Carol Berkin’s “The Bill of Rights”

Stephen Rohde reviews a book on of one of our nation’s most important political and historical documents: The Bill of Rights.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!