“The Last Jedi”: Saving Star Wars from Itself

By connecting female representation to values that challenge toxic masculinity, "The Last Jedi" supplants the franchise’s hero worship with compassion.

By Dan Hassler-ForestDecember 22, 2017

MY MOM has always hated Star Wars, even though I’m pretty sure she’s never seen any of the movies. I know she disapproved of it, because after my dad took me to see The Empire Strikes Back at the age of six, she wouldn’t let me have any of the toys, for purely ideological reasons. As pacifists and radical activists, my parents had agreed on a strict “no war toys” policy for me and my siblings. To my dad — an avid fan of Tolkien, Disney cartoons, and comic books — Star Wars action figures weren’t the same thing as G.I. Joe dolls. But to my mom, less easily seduced by the Dark Side of US popular culture, it seemed self-evident that Star Wars was about wars — and was therefore off-limits for us kids. The uncomfortable compromise my parents reached allowed me to keep the handful of toys my dad had already given me, but without their blasters, rifles, and other weaponry.

In spite of this personal history, which in many ways shaped my own lifelong obsession with entertainment franchises and fantastic fiction, I rarely questioned the cartoonish, spectacular, and seemingly innocent violence of the Star Wars movies. The Last Jedi, however, directly addresses the franchise’s glorification of mass violence in a subplot that introduces a political economy of arms dealers and exploitative capitalists profiting from conflict by selling weapons to both sides. It’s one of the slippery ingredients that make this eighth episode in the ongoing Star Wars saga a deceptively subversive film. Not only does it question and even challenge its own legacy, but it also accepts responsibility for a cultural phenomenon that is itself part of a frighteningly powerful media empire. This makes The Last Jedi a whole lot more than just another episode in an ongoing series; it is also a film that struggles to distance itself from the most toxic elements of Star Wars in order to chart a more progressive terrain.

In the years since Disney purchased Lucasfilm, we have seen Star Wars grow incrementally more radical in its representations of politics and ideology. The Force Awakens balanced nostalgic reassurance with a radical rebranding: under the Disney flag, it promised us that Star Wars was going to resurrect the comforting and familiar style of the beloved Original Trilogy, while at the same time rejecting the early franchise’s overtly masculinist and racist overtones in favor of a more progressive and inclusive representational politics.

Last year’s Rogue One repeated this strategy, again making a young woman the main protagonist and surrounding her with an almost comically diverse cast of supporting characters. But Rogue One also went further in its subversive representation of geopolitics. It offered an unambiguous response to the pathetic fanboys associated with 4chan, MRA movements, and the “alt-right,” who responded to the new films’ politics with hashtags like #boycottstarwars and #whitegenocide. Even if its notoriously troubled production resulted in a film that was less sure-footed than its predecessor, it left no doubt about its ideological agenda: released just weeks after the election of Donald Trump, the film drew a clear distinction between the Empire as a gang of fascist white supremacists and the Rebellion’s embattled coalition of oppressed minorities.

This holiday season, The Last Jedi once again combines the resurrection of nostalgic characters, props, and motifs with new and diverse elements. Helmed by Rian Johnson (known for his almost-too-clever plays on genre tropes in films like Brick and Looper), episode eight invokes our memories of The Empire Strikes Back in ways that are similar to, but also subtler than, Abrams’s more blatant nods to A New Hope in The Force Awakens. We spend more time with the major characters (both old and new) while an impeccably structured sequence of close calls, countdowns, and double bluffs distracts us from what is ultimately a deceptively simple plot.

But what lingers above all after the film’s dizzying 150 minutes of mythological reinvention, character development, good-natured humor, and breathtakingly staged action sequences is the degree of critical self-reflection that Johnson has woven into his thematically rich screenplay. An overwhelming anxiety of influence predictably permeates any new director’s attempt to elaborate on the world’s most famous entertainment franchise. In J. J. Abrams’s hands, this anxiety was clearly that of a fan-producer struggling to meet other fans’ expectations while also establishing a viable template for future installments. In doing so, his cinematic points of reference never seemed to extend far beyond the Spielberg-Lucas brand of Hollywood blockbusters that shaped his generation of geek directors, and he tried desperately to make up for what he lacks in auteurist vision with energy, self-deprecating humor, and generous doses of fan service.

But Rian Johnson is a filmmaker of an entirely different caliber. Just as Irvin Kershner and Lawrence Kasdan once added complexity, wit, and elegance to Lucas’s childish world of spaceships and laser swords, Johnson makes his whole film revolve around characters’ fear of repeating the past, and both the attraction and the risk of breaking away from tradition. His cleverness about transforming the Star Wars legacy is apparent in the smallest details: when the iconic battle on the ice planet Hoth looks like it’s about to be reproduced toward the film’s end, one character takes a moment to taste the white stuff on the ground and remark that it’s not snow, but salt. Such gestures clearly illustrate Johnson’s consistent strategy of playful trickery, while at the same time adding poetic resonance with the implicit suggestion, as Walter Chaw put it so perfectly, “that hope can even grow from salted earth.”

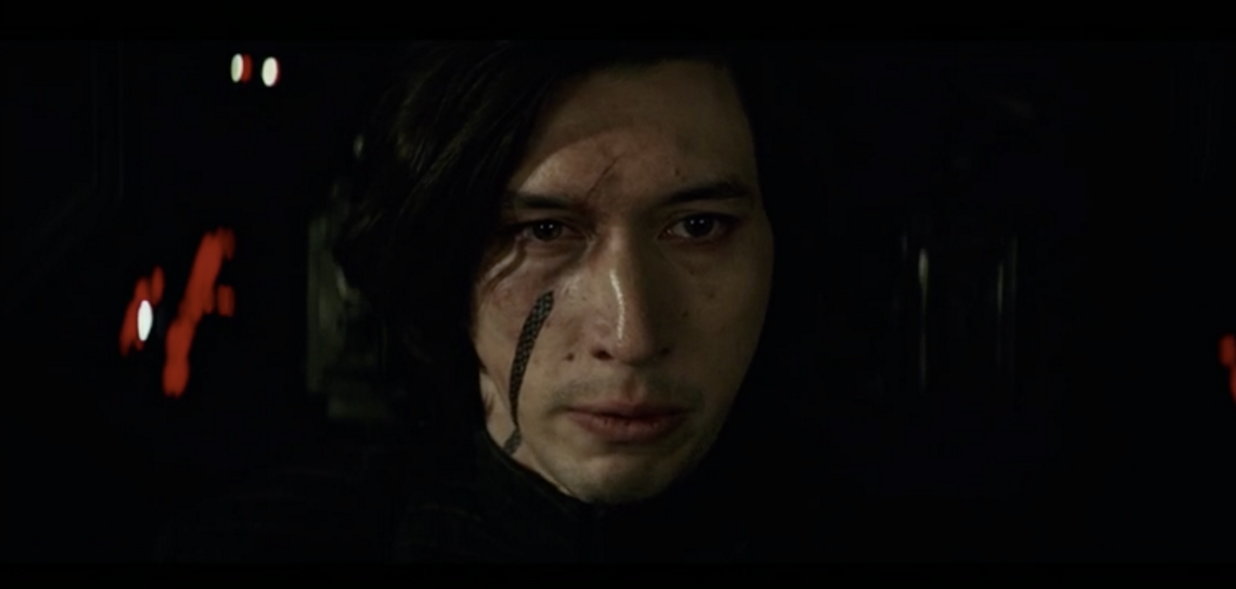

The same kind of ingenuity occurs on almost every level of the film as it performs constant summersaults and about-faces that both honor and subvert the Original Trilogy. The most telling moment of self-reflection is the remarkable scene in which Luke Skywalker, both accepting and subverting his role of reluctant Jedi Master, is forced to accept the idea that good students don’t follow in their teacher’s footsteps: instead they end up passing them by, moving on to bigger and better things. This is a courageous gesture from a young director stepping up to a franchise presided over by the legacy of a single author-god figure, zealously guarded by a deeply nostalgic fan culture, and deeply invested in cyclical narratives of patriarchal succession. The key struggle for the film’s two strongest characters revolves around a strikingly similar anxiety of influence, as Rey and Kylo Ren both face their contradictory desires to reproduce the past and to break free from the stifling weight of tradition and expectation.

But the real and lasting masterstroke in Johnson’s truly invigorating film is the way it connects the rejection of the Jedis’ patriarchal tradition to the roles played by women in the narrative. As important as it is to have more diversity in casting Hollywood blockbusters, diversity alone is not enough as long as narratives continue to serve the same old ideological purposes. Even if we might applaud the idea of a gender-swapped Ghostbusters, the results of gender-swapping will remain limited unless the reboot also addresses the original film’s political agenda. By the same token, we shouldn’t have to settle for Rey as simply a “female Luke”; her gender becomes meaningful only if and when it challenges the way capitalism’s violent and oppressive structures of patriarchal power have been deeply embedded in the Star Wars narrative.

This is where The Last Jedi makes a far more substantial effort to champion and incorporate real feminist values than either of its recent-era predecessors. Not content to merely include competent female action heroes like Rey or authoritative female leaders like General Leia Organa, Johnson’s film repeatedly opposes male characters’ impulsive and presumptuous actions with alternatives supplied by their female counterparts. This tension is introduced when the cocksure, ultra-masculine “laser-brain” pilot Poe Dameron defies Leia’s orders, refusing to back down from a battle he clearly sees as an opportunity to demonstrate his own heroism. But even though the scene plays out along lines familiar from the iconic Death Star assault, a crucial shift in perspective emphasizes first and foremost the sacrifices of the comrades whose lives Poe is so eager to put on the line. This reverses a redoubtable Star Wars tradition, in which everyone but the protagonist is sacrificed so the “real” hero can demonstrate his inherent superiority by blowing up the enemy in an orgasmic spectacle of explosive violence.

As my mother obviously intuited all those years ago, there is something deeply unsavory about the kind of pleasurable violence that Star Wars has unfailingly delivered. It’s a pleasure that emerges from a resilient obsession with totalitarian forms that Susan Sontag described with unflinching clarity in her famous essay “Fascinating Fascism”:

Fascist aesthetics […] flow from (and justify) a preoccupation with situations of control, submissive behavior, and extravagant effort; they exalt two seemingly opposite states, egomania and servitude. The fascist dramaturgy centers on the orgiastic transactions between mighty forces and their puppets. Its choreography alternates between ceaseless motion and a congealed, static, “virile” posing. Fascist art glorifies surrender; it exalts mindlessness: it glamorizes death.

It is difficult indeed to deny the dominance of precisely this kind of fascist aesthetic not just in Star Wars, but across Hollywood action movies as a whole. As early as 1978, Dan Rubey identified the beating heart of totalitarianism underneath all the layers of nostalgia, romance, and mythology that made Star Wars seem so “innocent.” Rubey argues that the film’s demand for the audience to submit to its massive technological apparatus reveals an underlying infatuation with fascism — from the film’s explicit citing of Riefenstahl to John Williams’s militaristic marches and Wagnerian leitmotifs, to George Lucas’s original instructions to make the Star Wars logo “very fascist.”

Perhaps the big question, then, is whether it is even possible for a franchise like Star Wars to rid itself of its own latent fascism. I would argue that this is where Johnson takes important steps in the right direction. The initial conflict between the increasingly aggrieved Poe Dameron and the women in leadership positions who surround him is echoed throughout The Last Jedi’s many plot strands: again and again, we see male characters’ self-centered and violent heroic ambitions challenged and corrected by female voices redirecting the narrative, always in the first place by refusing to glamorize death. And this tension is given nuance and emotional resonance by having the characters learn and grow from these encounters.

Thus, by connecting female representation to values that challenge and transform toxic masculinity, The Last Jedi attempts to supplant the franchise’s traditions of hero worship and redemptive violence with compassion, individual agency, and — startlingly, in a few brief moments — strategies of nonviolence. It even responds to those fans who have mistaken the storyworld’s Manichean structure for moral equivalence, reminding us that Star Wars is important to us not because it endlessly reproduces some meaningless eternal battle between good and evil, but because it dramatizes the much more urgent and contemporary distinction between right and wrong. And in this debate, The Last Jedi even suggests that the real source of evil resides not in some withered old man with magical powers, but in the lethal intersection between toxic masculinity and a disinterested class of “apolitical” capitalists who profit from an environment of endless war and conflict.

The key strength of The Last Jedi therefore lies in its determination to move beyond the original films’ formless mysticism and articulate clear moral and political values. When Finn is reminded at a crucial moment that the Resistance will win “not by fighting what we hate, but by saving what we love,” these words don’t come across as mawkish sentimentalism. In fact, the statement effectively sums up the necessity of positive and progressive goals for a radical left that has become increasingly reactive to the aggressive assaults of far-right movements. As Croatian activist and philosopher Srećko Horvat expounded in his recent book The Radicality of Love:

[T]he answer to the question “love or revolution” should be as simple and difficult (at the same time) as: love and revolution. Only here are we able to find the true Radicality of Love.

The radicality Horvat describes is one of sincere emotional investment in solidarity as a basic moral value. In The Last Jedi, Johnson draws on his own obvious love for Star Wars not only to move the franchise in exciting new directions, but also to subvert the franchise’s reactionary politics — while lifting a casual middle finger to the many fans for whom Star Wars has become a set of sacred texts. Without discarding the franchise’s long history, his intervention opens up new spaces that make this creaky old space saga feel vital and relevant to our cultural and political conversation, in ways the original films never did. And the film’s mawkish but disarming final moment speaks directly to the power these fantasies have to shape our values and ideals through the impact they have on children’s make-believe and gameplay. Call me crazy, but The Last Jedi may finally even convince my mom that Star Wars toys aren’t necessarily evil. Maybe I’ll give her a porg for Christmas.

¤

Dan Hassler-Forest teaches media studies at Utrecht University. His most recent book is Star Wars and the History of Transmedia Storytelling.

LARB Contributor

Dan Hassler-Forest is an author and public speaker affiliated with Utrecht University in the Netherlands. His research is focused on the ways in which popular media reflect changing social relations in late capitalism. His most recent books are Janelle Monáe’s Queer Afrofuturism: Defying Every Label and Janelle Monáe’s “Dirty Computer.”

LARB Staff Recommendations

How to Read Star Wars

"Star Wars is sacred to millions, and millions are blind to Star Wars." M. W. Lipschutz on the 13 ways of reading the franchise.

“Star Trek: Discovery” and the Dream of Future Fuels

Karen Pinkus contemplates “Star Trek: Discovery” and the future of fuel.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!