The Ghosts That Have Always Been Here: Queer Abuse in Carmen Maria Machado’s “In the Dream House”

“In the Dream House” follows Carmen Maria Machado making sense of and shedding her silence around her abuse, creating space for others to do the same.

By Rosa Boshier GonzálezNovember 18, 2019

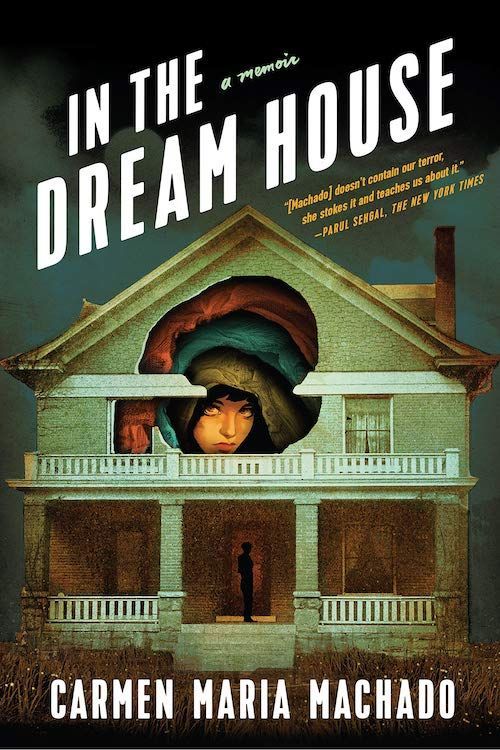

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado. Graywolf Press. 272 pages.

HOW DO YOU FIND agency in a world that denies your existence? Carmen Maria Machado charges at this question in her new memoir, In the Dream House, a kaleidoscopic account of queer abuse. Pointing to the historic erasure of queer trauma, Machado slices a former romance into a series of vignettes that range from the idyllic to the erotic to the steadily chilling, documenting the escalation of psychological violence between herself and former partner, referred to as “the woman from the Dream House.”

Beyond harrowing descriptions of emotional manipulation, written in the same visceral style that put Machado on the map as one of the most gripping literary voices of our time, Machado’s greatest grievance is with the social, legal, and political systems that authorize queer maltreatment through the erasure of Otherness. Machado begins her book, a robust yet personal critique of the archive and its inadequacies, by citing her primary source — Saidiya Hartman’s heralded essay “Venus in Two Acts.” Machado quotes Hartman’s strategy of “[w]riting history ‘with and against the archive,’ ‘imagining what cannot be verified.’” In an interview with The Creative Independent, Hartman says of “Venus in Two Acts”:

I observe that narrative may be the only available form of redress for the monumental crime that was the transatlantic slave trade and the terror of enslavement and racism. That’s a long way of saying that the stories we tell or the songs we sing or the wealth of immaterial resources are all that we can count on.

Taking direction from Hartman’s commitment to reenvisioning overlooked lives, Machado delves into narratives around queer abuse starting with her own, thus building scholarship around stories deemed impossible. Both Hartman and Machado use narrative to demand witness where agency has been barred. “The loss of stories sharpens the hunger for them,” Hartman writes, “So it is tempting to fill in the gaps and to provide closure where there is none. To create a space for mourning where it is prohibited. To fabricate a witness to a death not much noticed.”

Machado charts micro and macro erasures of queer experience. Drawing from José Esteban Muñoz (“Queerness has an especially vexed relationship to evidence…”), Machado highlights the ghostliness of queer identity within history, its echoes either destroyed (Machado references Eleanor Roosevelt’s letters to Lorena Hickok, burned by Hickok for their indiscretion) or ignored (Machado cites a court case in which an instance of queer domestic violence is dismissed due to the unfathomability of lesbianism; if it is unthinkable for a woman to love another woman, it is even more impossible for her to hurt one, leaving the victim ineligible for legal protection).

In centering Hartman and other thinkers like Jacques Derrida and José Esteban Muñoz, Machado compiles an alternative archive within her own archival research that counters historical narratives that uphold hegemony. She turns toward voices that tell the stories so many refuse to hear in order to express her own. When considering the archive, Machado asks the reader, “What gets left behind?” She answers for us: “Gaps where people never see themselves. […] Holes that make it impossible to give oneself a context.” In the Dream House tackles the politics of this gap: that it can neither be fully amended nor ignored. The archive is always incomplete.

Yet, despite the futility of correcting the archive, In the Dream House is a testament to hope. Machado enters the project with eyes wide open, aware that her perspective might be picked apart, met with anger, or worse, disregarded. With a clear belief in the power of testimony, Machado addresses silence and abuse in an era in which abuse is sanctioned and silence serves as survival.

Another In the Dream House primary source comes in the form of fairy tale. Drawing on a number of fairy tale tropes, Machado makes the fairy tale a field of study. Using meticulous footnotes, Machado catalogs fairy tale tropes and tracks how they manifest in real life. In doing so, Machado points out that there is not only danger in the stories that we don’t tell, but also in the ones that we do, innocuous as they may seem. By echoing stories that many of us can retell by heart, Machado points to internalized abuse. “Sometimes your tongue is removed,” Machado writes, “sometimes you still it of your own accord. Sometimes you live, sometimes you die. Sometimes you have a name, sometimes you are named for what — not who — you are. The story always looks a little different, depending on who is telling it.” Here, again, Machado points to the archive’s force, the power that the storyteller holds in their hands.

Machado expands her interrogation of the fairy tale to investigate the stories we create around our own relationships. Writing of the woman in the Dream House, Machado recalls, “Afterward, I would mourn her as if she’d died, because something had: someone we had created together.” Machado writes toward the human desperation to make sense of the forces that hold us down. This logic of fantasy plays into Machado’s prismic understanding of “The Dream House,” a metaphor for ideal love that changes from fantasy to nightmare.

Laden with high symbolism (“When it was humid, the front door swelled in its frame and refused to open, like a punched eye”), the further one reads the more the concept of the dream house multiplies, splinters itself. Machado ruminates on Derrida’s translation of the word “archive” to mean “the house of the ruler.” This spawns Machado’s fascination with “house,” and later “dream house.” Thus, the piece becomes a consideration on power, more specifically the power of documentation. “Dream” becomes a stand-in for the fallacy of queer justice: “dream” as in illusion, “dream” as in tall tale. “As we consider the forms intimate violence takes today,” Machado writes, “each new concept — the male victim, the female perpetrator, queer abusers’ and the queer abused — reveals itself as another ghost that has always been here, haunting the ruler’s house.” Yet, in Machado’s hands, “dream” is aspirational, a gesture toward recognition, a grasping toward documentation of queer experience in its myriad forms.

Machado walks the reader through the architectures of abuse. Like the archive, the logic of the abuser is a construction, a lie told enough times that it sounds like truth. This close association with abuser and archive suggests that the archive is itself abusive. What are the shared components of this abuse/archive architecture? As detailed by Machado: silence, control, blame. When a friend overhears the woman from the Dream House making Machado cry, Machado chides herself: “You haven’t successfully contained the situation.” She further drills down the responsibilities of silence placed upon victims by instructing, “it is important to live in unyielding fear with a smile on your face.”

Machado maps the incremental transfer of blame from abuser to abused — romantic dinner turned emotional burden, a sexual encounter unraveling into nightmare. “You love a good fight,” Machado’s abuser sneers at her, ostensibly in the middle of rehabilitation for her volatile anger. Yet, like many manipulative people, the perpetrator makes themselves the balm to the wound they have inflicted. After a fight that leaves Machado cowering in the bathroom, Machado’s ex gently asks her what’s wrong “in a voice so sweet it splits your heart like a peach.” As in her fiction, Machado deftly weaves horror into the everyday. Machado describes her abuser preparing Cornish hens for Thanksgiving: “She pulls out the spines and turns the birds over; presses them into the pan like open books.”

Throughout In the Dream House, Machado tracks the consequences of other peoples’ silences as well as her own — her mother’s failure to defend Machado against a homophobic aunt, the hidden violence between her former lover’s parents — painting how abuse is handed down if allowed to perpetuate. Further, Machado outlines silence’s detriments to the abuser as well as the abused. After the incident between her ex’s parents, Machado’s former lover expresses a fear of becoming like her father. In a later passage, Machado reflects on the infamous behavior of poet Edna St. Vincent Millay when Machado comes across a pile of broken gin bottles and morphine on Millay’s property that Millay’s housekeeker had discarded decades ago:

Edna treated her lovers, male and female alike, with no small amount of cruelty. She was talented but arrogant; brilliant but profoundly selfish.

And yet, there among the trees, seeing the measure of her pain, the proportions of her problems, I felt a stab of sympathy. It couldn’t have been easy to be married to her, but it couldn’t have been easy to be her, either.

In the Dream House follows Machado making sense of and shedding her silence around her abuse, creating space for others to do the same. “What is placed in or left out of the archive is a political act,” Machado writes. “I speak into the silence. I toss the stone of my story into a vast crevice; measure the emptiness by its small sound.” Undoubtedly, Machado’s memoir will inspire more stones, compiling an archive of lost stories and giving voice to those whose histories have been dubbed impossible.

¤

LARB Contributor

Rosa Boshier González is a writer, editor, and educator whose work has appeared in Guernica, Catapult, The New York Times, and Artforum, among others.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Emancipation of Little Women: On Library of America’s “March Sisters”

On the limits of archetype and power of self-mythology in “March Sisters.”

Shapes of Silence: On Michele Filgate’s Anthology “What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About”

Azarin Sadegh relishes the intimate and authentic personal essays that form editor Michele Filgate's "What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!