The Ghost of Punk

A review of Elizabeth Hand’s new “Cass Neary” novel, “Hard Light”.

By Rob LathamJuly 7, 2016

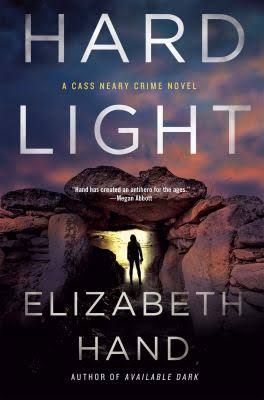

Hard Light by Elizabeth Hand. Minotaur Books. 368 pages.

IT’S HARD TO BELIEVE that the Elizabeth Hand who debuted, almost three decades ago, with the luxuriant science fantasies Winterlong (1988), Aestival Tide (1992), and Icarus Descending (1993) is the same author who writes the grim Cass Neary thrillers — Generation Loss (2007), Available Dark (2012), and now Hard Light (2016). While the former were lushly baroque tales of decadent far futures, reminiscent of Jack Vance and Gene Wolfe, the latter are stark, noirish crime stories featuring one of the most cynically amoral antiheroes since Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley.

Which is simply to say that Hand is a remarkably proficient writer who seldom repeats herself, even if her enormous flexibility — and her restless genre-shifting — has kept her from establishing a firm niche in the literary marketplace. Her books are always reliably crafted gems, be they dark fantasies like Waking the Moon (1994), post-apocalyptic slipstream SF like Glimmering (1997), or dreamy historical fantasies like Mortal Love (2004). As befits both its strength and its variety, her work has won the World Fantasy Award, the Nebula Award, the James Tiptree, Jr. Award, the Mythopoeic Fantasy Award, the International Horror Guild Award, and the Shirley Jackson Award.

This last-named prize, designed to recognize outstanding works of “psychological suspense, horror, and the dark fantastic” (and named after a similarly gifted and multifarious talent), was won by Generation Loss, the novel that introduced Hand’s misanthropic middle-aged heroine, Cass Neary. Cass, a once-celebrated underground photographer whose gritty work chronicled New York’s punk demimonde, including infamous shots of groupies and junkies, now spends her days stocking shelves at The Strand and her nights guzzling whiskey and uppers while spinning classic rock vinyl on her vintage turntable, probably the only valuable item (aside from her cherished Konica camera) in her crappy, rent-controlled apartment. Fiercely smart but content to dissipate her talent and energies, bisexual but unable to sustain lasting relationships with either men or women, a pathological liar and compulsive kleptomaniac, Cass is a seething cauldron of resentment, longing, and despair, and Hand does a remarkable job of making her both sadly credible and deeply sympathetic.

Her essential appeal lies in her take-no-prisoners bitchiness. Cass’s first-person narration is entirely absorbing, and readers are favored with a constant stream of put-downs of bourgeois normalcy that are razor sharp and hilarious. Here is her take on the denizens of a chichi London wine bar:

The guests appeared equal parts Young Bobo and Middle-Aged Money. Bespectacled guys in vintage band T-shirts or loose oxford-cloth shirts; women working the sexy anthropologist vibe with tribal tattoos and gaudy knitted headwear. I might have wandered into an Etsy conference, or a university faculty party.

Her scorn for the trendy hipsters who have mainstreamed the rebellious impulses that fueled her own youth is equally caustic — her anti-gentrification New Yorker spirit follows her across the pond, where she likens Camden Market on a weekend night to “a high-school prom where the theme was ‘Masque of the Red Death.’”

Even her few friends are vaguely terrified of her, their affectionate nicknames edged with anxiety: “Scary Neary,” “Cassandra Android.” Painfully aware of herself as a scruffy punk dinosaur, Cass revels in an almost nihilistic contempt for the respectable and up-to-date — an attitude mirrored in her old-school commitment to “real” film, whose physicality she views as more sensuously authentic than digital media (though she does finally acquire a smartphone camera in Hard Light).

As befits their titles, each of which puns on some aspect of photographic practice, the three novels’ plots center on puzzles spawned by the theory and history of photography. In Generation Loss, Cass travels to a gloomy island off the coast of Maine where she becomes embroiled with a sibylline artist and her erstwhile consort, a demonic hippie whose weirdly manipulated pictures hold a promise of unfathomable darkness. In Available Dark, she falls in with a crew of occult black-metal musicians and their paparazzo, whose high-gloss photos seemingly depict a series of ritualistic crimes. Hard Light finds her down and out in London and Penzance, where she negotiates the physical and moral ruins of a ’60s-era commune still held together by a hallucinatory underground film.

Aside from their immersion in the quirkiest of shutterbug lore, the novels are linked by an abiding fascination for outsider art of all kinds: post-punk and no-wave music, cult movies, bootleg tapes of dubious provenance and questionable legality. The stories have a vague sheen of the supernatural, with Cass functioning as a kind of dousing rod for occult intrigues, often emanating from the wasted remnants of ’60s counterculture. Hard Light is the most developed example of this trend, with Cass tracing the decay of a sybaritic community of pagan revelers, whose main spoor is the notoriously unwatchable movie Thanatrope. “You can find a few conspiracy theorists who believe there’s an arcane message encoded into the film,” she observes, “or a curse activated every time the movie’s shown.” Unlike earlier cursed-movie novels such as Ramsey Campbell’s Ancient Images (1989) or Theodore Roszak’s Flicker (1991), the supernatural aspect remains ambiguous, but there is no doubting the film’s sinister ability to pile up corpses in its wake. Indeed, there are few characters Cass encounters in the story who do not meet some awful doom, and the death toll of all three books is strikingly high. It isn’t entirely clear, at the end, whether her long-lost lover Quinn, with whom she was reunited in Available Dark, has managed to survive the carnage.

Hard Light, like its predecessors in the series, is compulsively readable, but taken altogether, the effect is of a highly improbable concatenation of events. After all, Cass, by her own admission, had been eking out a miserably routine existence for decades before being summoned to the blighted Maine island in Generation Loss. The events of Available Dark and Hard Light follow immediately thereafter; in fact, the time frame of all three books barely spans a month, during which period Cass narrowly escapes three crazed, borderline-Satanic serial killers. No rest for the wicked, indeed.

That said, the novels are unfailingly funny and shrewd, erudite in their punkish way; they are also at times truly terrifying. Hand is an expert at evoking atmospheric milieux, from the wilds of an offshore island to the urban deserts of modern Europe. Like Cass, she is a master at capturing the interplay of light and darkness, and she does not flinch from the most graphic brutalities. Her eye is penetrating and sure. And in Cass she has found a once-in-a-lifetime character whose ferocious narrative voice spares no one, not even herself. “I’m the ghost of punk,” she opines, “haunting the twenty-first century in disintegrating black-and-white; one of those living fossils you read about who usually show up, dead, in a place you’ve never heard of.” She has, as noted, managed to survive thus far, though not unscarred by her grim adventures. Like many readers, I look forward very much to her next scabrous descent into the underworld.

¤

LARB Contributor

Rob Latham is the author of Consuming Youth: Vampires, Cyborgs, and the Culture of Consumption (Chicago, 2002), co-editor of the Wesleyan Anthology of Science Fiction (2010), and editor of The Oxford Handbook of Science Fiction (2014) and Science Fiction Criticism: An Anthology of Essential Writings (2017).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Hollywood’s Punks

"Under the Big Black Sun" conveys how exciting and important it felt to get up on a stage and scream into a mic to other passionate freaks at a...

Low Art

An interview with Denise Mina about crime writing and low art.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!