The Future Is Black, Not Bleak

David Michael Jamison reviews “The Future of Black,” edited by Len Lawson, Cynthia Manick, and Gary Jackson.

By David Michael JamisonJanuary 22, 2022

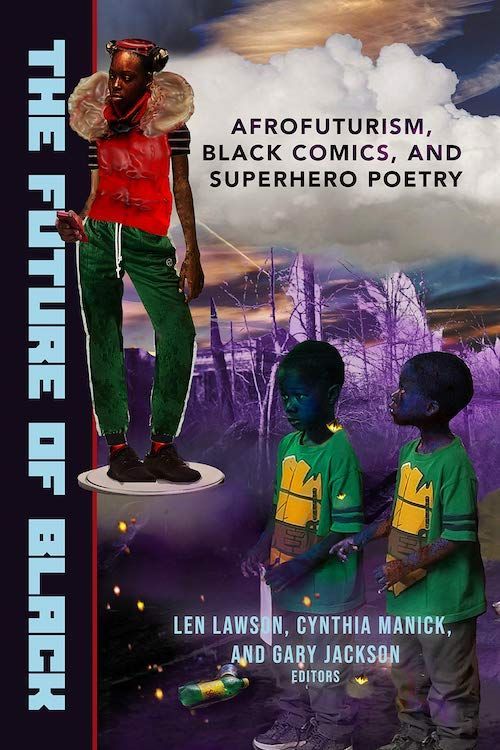

The Future of Black: Afrofuturism, Black Comics, and Superhero Poetry by Len Lawson, Cynthia Manick, and Gary Jackson. Blair. 234 pages.

FOR THE FUTURE OF BLACK: Afrofuturism, Black Comics, and Superhero Poetry, editors Len Lawson, Cynthia Manick, and Gary Jackson have amassed a formidable collection of talent: Black college professors and published authors from all over the country writing on themes that the editors have aggregated under the term Afrofuturism. Although there have been a number of anthologies of Afrofuturist fiction, you might be hard-pressed to find one centered on poetry, and for that reason alone, this is an important publication.

If you are unfamiliar with the term Afrofuturism by now — well frankly, that is just hard to believe. It is far more likely that you have heard of it, but then subsequently heard such a lazy-hazy esoteric definition of it that you immediately filed it away as something that you would spend time thinking about later. And that is not without good reason. Although the concept of Afrofuturism is the subject of substantial academic study, many of the people who actually talk about it are nonacademic literati and bohemians — the types who are far more likely to want to “vibe” with you about it than expound upon the diasporic collective imagining-into-becoming that the concept of Afrofuturism explores. Each of the three editors of The Future of Black offers up their own definition of the term: “invading spaces that purport Blackness as inferior” (Lawson); “a revolutionary act [in which Black people] imagine ourselves with the stars, bulletproof” (Manick); and “imagining distant, and not-so-distant landscapes […] illustrating the everyday disasters and miracles of what it means to be Black today, tomorrow, and yesterday” (Jackson). All those definitions work, really, in quite good harmony with each other. Here is mine: Afrofuturism is a struggle against the marginalization of the African diaspora as industrial, technological, and aeronautical capitalism expands globally, and then transglobally. Put another way: The farther out into space the white man gets, the further into the shadows racism and injustice will be swept. But Afrofuturism imagines a future where Blackness is/can be valued; where the African diaspora always played an integral part in the economic development of the West. And one thing that is clear about Afrofuturism is that any member of the Diaspora gets to define it for themselves.

There is no better way to do so than with poetry. The Future of Black’s first few chapters are dedicated to superhero poetry, and it is here that the book is sure to have its most magnetic resonance with today’s popular culture. Because, in a sense, superheroes have become America’s new gods. As American churchgoing has eroded and Americans have become more inured to the commercialization of religious icons, superheroes have swooped in where the dusty narratives of Greek gods have dried up. Comic book heroes are Joseph Campbell’s mythic, flawed heroes inked, printed, and splayed in glossy format across 10-by-13 inches of new pulp, pumped out monthly. The Future of Black is best in its first chapter, “Man of Steel,” which opens with a four-cycle series of notes to Superman by National Book Award–winning poet Lucille Clifton. This chapter captures the African American angst of wanting to be considered part of the American story, as well as the petulant coping strategy of rejecting America before it can reject you. Because no truth can be laid barer than the truth that Superman never really spent any quality time in the Black community. Clifton huffs at his neglect in the first poem of the book, “if I should,” in which she portrays a fraught domestic scene: “if I should walk into / that web, who will come flying / after me, leaping tall buildings? / you?” Think about it: in all the years Superman was stopping bad guys, why did he never stop any bad guys in the ’hood? The ’hood has plenty of bad guys. How come he never rescued any little Black girls? Why did he leave Clifton only ever “dreaming your x-ray vision / could see the beauty in me” as the book’s third poem, “final note to clark,” opines? In the book’s fifth poem, Frank X Walker’s response to Clifton, entitled “new note to clark kent,” conquers Superman like Lex Luthor never could. Here Walker peeks beneath the cape and calls out the Man of Steel for not even having the superpowers to battle racism. “you powerless against the kryptonite of rich man and hate man,” he tells the white god.

The next chapter is an ode to “superheroes who looked like us” called “Black Superheroes.” For my generation, that means the wave of superheroes that popped up after the 1960s — heroes like Black Panther, Storm, and Luke Cage. This chapter most encompasses the inner work necessary to be an Afrofuturist because it is in this chapter that one most sees poets identifying with or fantasizing themselves as superheroes. Nine out of the 14 pieces in this section either discuss what it would like to be a superhero or simply embody the hero as first-person narratives. What this chapter makes clear more than any individual poem in the book is that what superhero mythology is really about is a god-fantasy — that people of all races share — to have powers beyond that of other mortals. And when comic book writers finally prioritized diversity for the 1960s counterculture, Black superheroes served as long-sought avatars for Black comic book fans.

Next follows a “Black Antiheroes” chapter that presumably features Black villains, but this chapter is unnecessary, because most “Black villains” are more misunderstood than simply evil. The villains here include characters like Raven, Lando Calrissian, Amanda Waller, and Eartha Kitt’s Catwoman. But should any of these characters really be considered antiheroes? Raven’s father was a demon — who could blame her for occasional lapses in judgment? And even in Star Wars space was mostly white, so you have to imagine that Calrissian had to overcome some sort of prejudice to become baron administrator of Cloud City. When he betrayed Han Solo, yes he betrayed his friend, but he saved his city. And who knows what kind of obstacles Amanda Waller faced to become one of the highest-ranking members of the US government, albeit a shadow ranking? And Eartha’s evil derived mostly from the fact that she deduced that the most practical way for her to win in the white-male patriarchy was to sexualize herself, despite her many talents. Antiheroes? No. Brothers and sisters trying to cope, mostly.

A gem is Tara Betts’s “To Lieutenant Nyota Uhura” from the “Black Pop Culture” chapter. This poem should be sent to Nichelle Nichols immediately. It is a cold-blooded breakdown of how vital a real Lieutenant Uhura would have been on the Enterprise, and probably was when the cameras stopped rolling. At one point, Betts as narrator queries the lieutenant: “Did the Vulcan ever ask you / how it feels like to be different? / He removed his pointy ears and brows daily, / ruffled his hair to normalcy.” Ahh, the stinging cut. In real life, Nichols was far more of an “alien” to 1960s American identity than Leonard Nimoy was. Narrator Betts later also serves shade to Lieutenant Sulu for sitting by watching, minority-impotent, while Captain Kirk disrespected his sister of color. But Betts’s special gift might be more in her command of letters and words than in her biting social criticism. She rumbles off the first stanza in a crisp iambic tetrameter with lovely color imagery and movement tropes (“jet black curl whipped,” “red line sleek against thigh”), and then polishes it off with a smart ode to the letter B: “Thigh, calves interrupted by / black boots, / but first, benediction.”

Casey Rocheteau’s pictographic “Sun Ra Speaks to Gucci Mane” is pretty close to genius, a dressing down of the trap godfather by the Afrofuturist-music pioneer, arranged typographically into an Egyptian pyramid. The pictogram is an ode to Ra’s Afrocentric origin story, in which a race of space aliens sent him to Earth to be born (the implication here is that Black people live in space and had already mastered interstellar transportation). Ra claimed that ancient Egypt had far more culture and cosmic resonance than anything Earth had in the modern world, but we had by now been corrupted by a love for material things. Here, Rocheteau imagines Ra having a talk with Gucci Mane, a man who seems to define himself by his attachment to material wealth — most particularly diamonds, one of Africa’s most exploited resources. Sun Ra’s cryptic queries of the rapper’s values is a bold statement on how fundamentally Afrofuturism will have to supplant the Western materialist mindset that has become so central to hip-hop — arguably Black America’s most successful cultural export.

The “Video Games & Fantasy” chapter provides an interesting look into what might replace comic book lore as the West’s new mythological source material. The existence of video game poetry suggests an impact on American culture that is somewhat jarring, since the video game genre is so much newer. Gaming only reached mainstream pop culture status in the late 20th century, while comic book lore has been mainstream since the 1950s and survived the changes of the countercultural movement, which gave rise to characters like Storm, Luke Cage, and Black Green Lantern John Stewart. There is also a significant class component to video game lore — it began as mostly the realm of upper- and middle-class Black kids in the 1980s. It was where Town and Gown diverged; where Blacks kids from the ’hood did not relate because they were lucky to get a PlayStation and luckier if they ever got their turn to play. There is also a generational divergence. In the 1980s, you could get away at school with not knowing things like the characters in Mario Bros. or Zelda’s backstory. By the 2000s, however, it had become socially unacceptable for young people to not have cultural purchase over these video game narratives, and so poor kids began to watch rich kids play (usually at sleepovers) like entertainment. Today gaming is as ubiquitous across classes as cell phones, perhaps signaling a futuristic trend that also bespeaks the nature of Afrofuturism itself.

The “Video Games & Fantasy” chapter contains this poetry collection’s most interesting piece, as well. Douglas Kearney’s “But, Black, It Can’t—” is a graphic poem that really shouldn’t be considered a poem at all, but is more like a literary work of art. It is clear that the piece either was or should have been influenced by Jean-Michel Basquiat’s fusion of graffiti literature with shape, form, and color. Here Kearney seems to be crafting a literary response to graffiti art in the form of a geometric arrangement of Lichtensteinian speech bubbles, industrial-font captioning, a mathematical graphing of the bass clef, and musings on the word “loop.” The poem merges the concept of loops in hip-hop with a cuirass — armor that might protect the listener from … What? I do not know. Kearney also merges explorations into the geometry of a loop in there somewhere — the piece is unintelligible, unpredictable, exhilarating, frustrating, and the bravest thing in the book.

Three stellar pieces are set sequentially in the chapter titled “Black Women Narratives”: Teri Ellen Cross Davis’s “The Goddess of Anger,” Ashley M. Jones’s “Friendly Skies, or, Black Woman Speaks Herself into God,” and Tim Fab-Eme’s “Mitochondrial Eve.” Including this chapter in this collection seems a bit forced, as if listening to women’s voices were a futuristic concept in the Afrocentric community rather than an ancient African concept that had been lost in the haze of Western patriarchy. All of these poems in particular sing, and all for different reasons. Davis’s selection is a monologue, addressed to a(ny) woman, from the Goddess. And that B is about to go off. As you read, you immediately recognize all the Black women you know who have, from time to time, invoked this particular deity. And Davis captures Her adroitly. Jones’s piece is an exquisite and surreal recentering of the perspective we place on the hero of an airline flight — the white male pilot — to the Black female flight attendant. It is she who, Jones observes, is actually visible, and dealing with her fellow humans, and looking us in the eye as she assures us that everything will be alright. She is the one whose word we actually trust, not the disembodied automaton’s voice we hear over the loudspeaker at the flight’s beginning and end. Fab-Eme’s offering is a simple, holistic rewriting of Genesis, again recentering female energy as the Logos who spoke (not spoke, birthed) the universe into existence.

In the chapter “Afrofuturism and Speculative Poetry,” mention must be made of Quincy Scott Jones’s hilarious and deceptively irreverent thought-poem “Untitled,” about the suicidal musings of an android. Because while Jones describes the android, one becomes eerily aware that all the upgrades and chemical cocktails that compose the machine have parallels in the human prosthetic and pharmaceutical industry. Put more terrifyingly: The rise of medical technology has made it such that people who ingest “protein electrolyte supplements,” and regularly employ things like a “GPS wireless touch-tone” are really … partly … becoming sort of androids anyway. Even though Jones defines the android as “part biology, part technology,” cannot today’s modern humans make the same claim about themselves? And, again, capitalist accumulation does not help, because the android buys every possible upgrade to keep itself alive, even past its preprogrammed termination date. Instead of “death,” the android suffers the eventual fate of all unrecyclable industrial commodities — existing in obsolescence.

My most pointed criticism of The Future of Black is a criticism of the state of Black poetry: that of the impact of the spoken-word/slam-poetry phenomenon that rocked America’s coffeehouses in the late 20th century. By the time Love Jones came out, poetry slams had become so popular that published written poetry began to read more and more like it had been lifted from the performance stage. I am not the first person to discuss this, and others with far more expertise have expressed it more eloquently, but the crux of the argument is: Performance poetry should be composed for the stage and written poetry should be composed for the page. The craft of written poetry expresses thought through the use of letters and words and the sounds they make. Performance poetry, however, employs other media — the human body, voice, intonation and accent, etc. When you mix those two genres, confusion can ensue. Unfortunately, many of the poems in The Future of Black have the tendency to simply read like someone is talking, which is only compelling if the rhythm has either natural or evocative resonances, which they seldom do here. And although this critique might lead the reader to believe that I have a low opinion of performance poetry, that is not the case. I do indeed have a low opinion of scoring, as well as of the mechanical repetition of performance tropes in slam poetry like the singing of song lyrics or long, drawn-out vowels. But I do love the spoken word; I am a spoken-word artist myself, which is why I wince at seeing it written on the page.

But these are minor critiques of a collection that has bigger and bolder statements to make. Aside from the fact that the Black Women’s Narrative chapter should probably be its own book, The Future of Black is a necessary compendium of early 21st-century Afrofuturistic verse and thought.

¤

David Michael Jamison is assistant professor of History at Edward Waters University and was formerly visiting assistant professor of Black World Studies at Miami University–Middletown. He has written reviews for publications such as The International Journal of African Historical Studies, H-Net Reviews in the Humanities and Social Sciences, and The Open Textbook Library. His website is: www.davidmichaeljamison.com

LARB Contributor

David Michael Jamison is assistant professor of History at Edward Waters University and was formerly visiting assistant professor of Black World Studies at Miami University–Middletown. He is also a playwright, writer, and community activist. He has a doctorate in African Diaspora History from Indiana University and a bachelor’s degree in English from UCLA. He has book reviews in such publications such as The International Journal of African Historical Studies, H-Net Reviews in the Humanities and Social Sciences, and The Open Textbook Library. Before becoming an academic, Dr. Jamison was a public high school English teacher in Brooklyn, New York, then in South and East Los Angeles. He has attended and presented at several international conferences on Africana Studies. He lives in Jacksonville, Florida, with his wife and daughter. His website is: www.davidmichaeljamison.com

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Future Is Divergent: On “Literary Afrofuturism in the Twenty-First Century”

“Literary Afrofuturism in the Twenty-First Century” stands firm in the messiness of it all, proclaiming that said messiness as, in fact, a part of...

To Overcome Shouting into the Void: A Conversation with Jae Nichelle

A spoken word poet discusses her craft, the dangers of commercialization, and the inspiration of Black Lives Matter.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!