The Fragility of Politics: What Paul Ricoeur Can Teach Us About the French Election

Robert Zaretsky explores how Paul Ricoeur’s ethics inform Emmanuel Macron’s politics.

By Robert ZaretskyMay 7, 2017

IN THE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS to Memory, History, Forgetting (2004), his last major book before his death in 2005, the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur thanked an editorial assistant for his “pertinent critique” of the manuscript. Two weeks ago, that same assistant — and France’s next president — Emmanuel Macron, faced an angry and desperate crowd of soon-to-be-laid-off workers. As Macron approached a rippling sea of hostile laborers in a Whirlpool factory parking lot in Amiens, France, a more vivid setting for Ricoeur’s reflections on politics and morality could hardly be imagined.

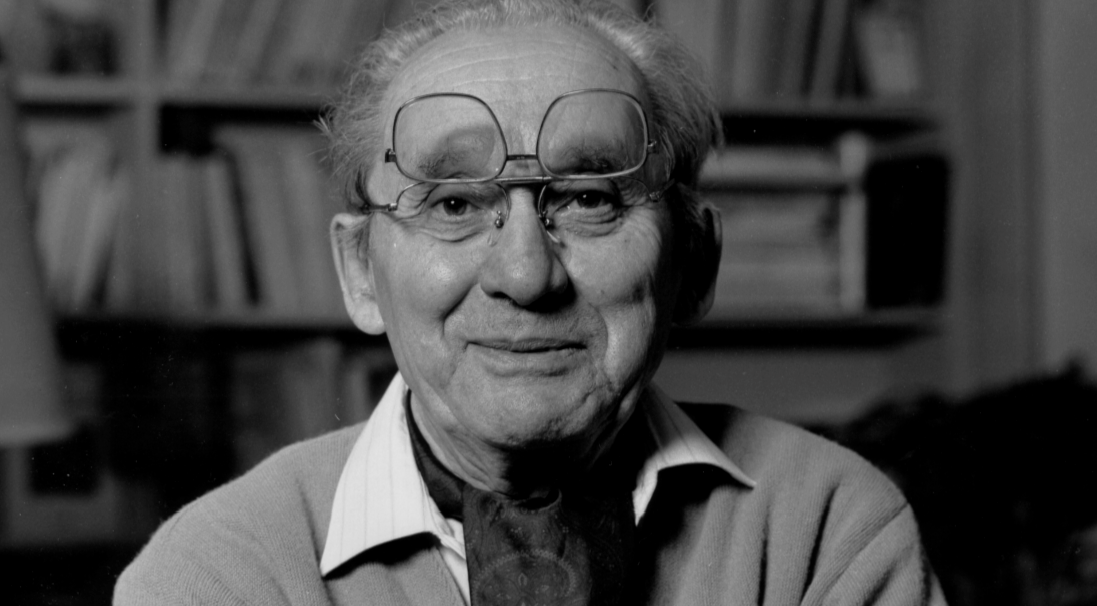

Though he never achieved the same celebrity or notoriety in the United States as did Michel Foucault or Jacques Derrida, Paul Ricoeur was, ironically, the most “American” of his generation of French intellectuals. Not only did he teach for several years at the University of Chicago, but his works are also exceptional — at least among French philosophers — for their knowledge and engagement with Anglo-American thinkers ranging from P. F. Strawson and Alasdair MacIntyre through John Rawls and Michael Walzer to Frank Kermode and Wayne Booth. (In a typically self-effacing remark, Ricoeur once told an interviewer that he held a chair at Chicago “with a schizophrenic title; it was called ‘theological philosophy’ or ‘philosophical theology,’ I don’t remember which.”)

Equally unusual was Ricoeur’s parcours, or career path. Rather than a product of the grandes écoles — the parallel system of higher education for the nation’s best and brightest — Ricoeur graduated from a provincial university in Brittany. Indeed, growing up in this most Catholic of French regions underlined yet one more peculiarity: Ricoeur was a practicing Protestant. At the end of World War II, which Ricoeur spent in a German POW camp, he went to teach at the Protestant Collège Cévenol. An international school dedicated to pacifist ideals, the Collège Cévenol — still open these many years — is nestled in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, the Protestant village that, as the world discovered many years later, saved the lives of roughly 5,000 refugee Jews during the war.

Though a Protestant, Ricoeur was the most ecumenical of thinkers: during a half-century of teaching and writing, he ranged over a vast array of fields. He left important marks in biblical and literary criticism, coining the striking phrase “the hermeneutics of suspicion” to describe the narrative and philosophical strategies used by Nietzsche, Marx, and Freud to unmask the “lies and illusions of consciousness.” No less importantly, Ricoeur has also influenced the work of theologians and historians, legal and psychoanalytic theorists. (At least when not alienating them: after telling Jacques Lacan in 1963 that he could not understand a word of his writings on Freud, Ricoeur became the bête noire of Lacan’s followers.)

Despite Ricoeur’s dizzying variety of interests, a small number of concerns and convictions run long and deep through his writings. Ricoeur was not an apologist for suspicion, but instead a defender of humanism, one who saw opposing ideas or ideals not in terms of dichotomies, but in terms of dialectics. Inevitably, he allowed, there is tension, at times great, between the opposing positions. But this tension can produce, if not a synthesis, at least a deeper appreciation on both sides of the other’s position. Take, for instance, Ricoeur’s use of the German sociologist Max Weber’s well-known distinction between the ethics of conviction and the ethics of responsibility. The former insists on striving for an ideal, regardless of the cost to oneself or others; the latter insists that, when necessary, ideals must cede to our fundamental duties toward fellow human beings. Aware of the harrowing consequences, at times, of the collision between these two ethical systems, Ricoeur nevertheless views their tension as a test, not a contest — an occasion that obliges us to reflect on what is, at that moment and in that place, most important, and asks us to choose as best we can with what we know. The choice will rarely be straightforward, yet remaining true to one’s ethical imperative is less urgent than remaining lucid about the situation’s tragic complexity.

For Ricoeur, phronesis, Aristotle’s term for prudential or practical wisdom, is the tool we bring to bear on political or social puzzles in order to piece them together as best we can. There is no single method or blueprint in the application of phronesis, as circumstances will always differ. For this reason, Ricoeur argues, phronesis flows not from a moral code — rules that claim a universal and normative status — but instead from an ethical life. In his trenchant work Oneself as Another (1992), Ricoeur privileges ethics over morality, arguing that ethics is grounded in aiming our actions — at times mistaken and always laden with risks — at “a good life with and for others in just institutions.”

The ethical life, one that allows for our individual and collective flourishing, requires seeing oneself as another. “Fundamentally equivalent,” Ricoeur argues, “are the esteem of the other as oneself and the esteem of oneself as another.” When we take the full measure of phrases like “you, too” and “like me,” we acquire a deeper sense of solicitude, one in which sympathy is not an exterior value we adopt, but an interior sense we shape. The capacity for critical solicitude makes us more alert — more vulnerable, really — to the suffering of others. Critically, as Ricoeur underscores, such suffering is not only physical or psychological, but is also defined by “the reduction, even the destruction, of the capacity for acting, or being-able-to-act” and thus becomes “a violation of self-integrity.”

Not unlike the condition of the Whirlpool workers, who were waiting not just for Macron but also for the day when they would become redundant. Earlier that same day, learning that Macron planned to meet nearby with the factory’s union representatives, his opponent in the presidential race, Marine Le Pen, made a surprise visit to the factory. Leader of the anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, anti-Europe, and extreme-right National Front, Le Pen lambasted the free market policies — embodied, she declared, by Macron — that had led to the factory’s decision to relocate to Poland. This, she vowed, would not happen under her watch. Putting the finishing touch on her public relations coup, Le Pen then took dozens of selfies with the workers, who though they historically vote for the left, were nevertheless thrilled by Le Pen’s seeming solicitude and sympathetic convictions.

Widely seen as a technocrat who made his fortune as an investment manager at Rothschild & Co., as well as the glistening product of the very grande écoles that his mentor Ricoeur never knew, Macron was left with what seemed a public relations disaster. But faced with potential catastrophe, a student of Ricoeur would see an opportunity, even a duty. Following his meeting with the local union leaders, Macron went to the factory, waded into the crowd of workers, and, with megaphone in hand, launched into a sharp and blunt give and take with the workers.

Inevitably, from the fringes of the crowd, there arose catcalls and insults, but in the tense face to face between Macron and those closest to him, the confrontation gave way to the beginnings of dialogue. Distinguishing himself from Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the leader of the extreme left Defiant France, Macron declared: “I will not promise that I will nationalize your factory. The answer to what is happening is not to suppress globalization or close the borders. Do not be fooled by those who tell you otherwise. They are lying to you. Unhappily, there will always be companies that fail.”

When a worker demanded to know what Macron would do as president, he vowed that his government would invest heavily in retraining programs for endangered industries. Hearing frustrated groans, Macron replied by telling the workers that he did not come to “promise the moon,” but instead that he would fight for them: “We all have responsibilities. If I did not respect your work, your fears, and your anger, I would not be here today.” He then made one more promise: “I will return, without cameras and even if I lose.”

The recognition of the other’s singularity, the recognition that there are no simple solutions and that confrontations must become dialogues — creating a space, even in parking lots, where answers might not be found but questions will find respectful listeners — all reflect the ethics proposed by Macron’s teacher. So, too, does Macron’s repeated invocation of promises, both those he would make — such as returning to Amiens to meet the workers — and those he would not, like Le Pen’s to keep Whirlpool’s operations in Amiens. By making a promise, Ricoeur argues, one not only shapes the expectations of the other but also those one has of oneself. When we make a promise, we pledge fidelity to the one for whom it is made, making our future selves hostage to the other’s esteem. No less important, though, we also, by taking the full measure of the promise, make ourselves more coherent and more worthy of self-esteem over time.

Ultimately, for Ricoeur, the consistency and cogency of our lives must be judged by our attachment to the promises we make to ourselves and to others. When he served as doyen at the University of Paris at Nanterre during the student rebellion of 1968 and 1969, Ricoeur attempted what Macron did at the Whirlpool factory. When he learned that a group of student radicals forbade professors to enter the cafeteria, Ricoeur nevertheless walked into the room in the hope of dialogue. Instead, one of the students, approaching him with the lid of a garbage can, placed it on top of Ricoeur’s head. This tableau, which could easily have been repeated with Macron at Whirlpool, grimly illustrates what Ricoeur called the fragility of politics. Fifty years later, politics have become, if anything, even more fragile. The consistency and cogency of the French Republic, threatened by a new generation of ideological extremists, will also live, or die, by Macron’s ability to live up to his own promises.

¤

¤

LARB Contributor

Robert Zaretsky teaches in the Honors College at the University of Houston. His books include Nîmes at War: Religion, Politics, and Public Opinion in the Gard, 1938–1944 (1994), Cock and Bull Stories: Folco de Baroncelli and the Invention of the Camargue (2004), Albert Camus: Elements of a Life (2010), Boswell’s Enlightenment (2015), A Life Worth Living: Albert Camus and the Quest for Meaning (2013), and Catherine and Diderot: The Empress, the Philosopher, and the Fate of the Enlightenment (2019). His newest book is Victories Never Last: Reading and Caregiving in a Time of Plague.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Post-Interest Politics

Are we looking at a political realignment?

Political Surrealism, Surreal Politics

China Miéville takes on Surrealism, exploring how to be as radical as reality in art and in politics.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!