The Earnest Liar: Joe Ollmann’s “The Abominable Mr. Seabrook”

Who was William Buehler Seabrook? And does Joe Ollmann's new comic biography of the journalist answer this question?

By Jacob BroganMarch 19, 2017

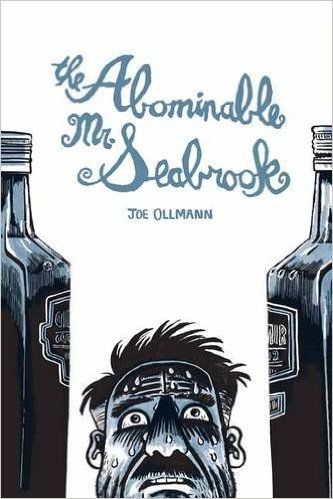

The Abominable Mr. Seabrook by Joe Ollmann. Drawn and Quarterly. 316 pages.

MIDWAY THROUGH Joe Ollmann’s remarkable graphic biography The Abominable Mr. Seabrook, I found myself temporarily convinced that I was reading a work of fiction. An early 20th-century journalist and travel writer, William Buehler Seabrook was once, Ollmann claims, among the most successful wordsmiths of his day. In Ollmann’s telling, Seabrook was a progenitor of both gonzo journalists and contemporary Vice contributors, his work anticipating the former by decades and the latter by almost a century. As the book takes us through Seabrook’s life, implausible experiences accumulate: he joined camel raids in Arabia, attended voodoo rites in Haiti, and supped with cannibal kings in Africa. Along the way, he became friendly with Aleister Crowley, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and many of the other most notorious figures of his era. And yet I was sure I’d never heard of him.

Though many of Seabrook’s works are still available, some of them newly reprinted, it was his connection with Stein that finally confirmed his existence for me — in particular his appearance, cited by Ollmann, in Everybody’s Autobiography (1937). Paging through my copy of that little-loved volume, I found the promised reference, tucked away in Stein’s story about telling a story about her brother. Only later did I begin to remember other confirmations of Seabrook’s historical reality: a lexicographic fragment on the history of the word “zombie,” which Seabrook helped popularize; the scandalous wonder of finding his book Witchcraft: Its Power in the World Today (1940) on the shelves of my grade school library. Seabrook was real, then, but even the evidence of his reality felt touched by the unreal — like a dream that exactly recreates an incident from the day before, minus a few critical details.

For all that, Ollmann’s book is meticulously researched, hewing carefully to the facts. At times, he sets dialogue in quotation marks, indicating, as the words sprawl out of his characters’ mouths, that he’s drawing on journal entries and letters. Measured and precise, virtually every page of The Abominable Mr. Seabrook is a triumph of technical cartooning, relying almost exclusively on strict nine-panel grids that impose a sense of clarity and order on even the most hectic experiences. In one typical sequence, Ollmann zooms in slowly on Seabrook’s face over the course of three frames as the journalist peels and eats a banana, having just realized that the human flesh he had begged to try is nothing more exotic than a gorilla carcass. Though Seabrook’s features remain impassive, the quick-tightening illustrative rhythms tell us all we need to know about the journalist’s mindset. He realizes he’s been had. He’s disappointed. He’s already planning his next steps.

And plan them he did. Committed to telling the story he wanted to tell — and to telling it as truthfully as he could — he would later bribe a French morgue attendant to slice off a bit of “neck meat” from a cyclist killed in an accident. Have you heard that human flesh resembles veal? You likely learned as much from Seabrook, who, according to Ollmann, had this purloined cut prepared three different ways by the chef of an acquaintance. Nevertheless, in his 1931 Jungle Ways, Seabrook still claimed he had learned the taste on his travels, only admitting to the real story in subsequent writings, after the flush of alcoholism had supplanted the long blush of fame. This is Ollmann’s Seabrook in miniature, a truthful man who often explored dubious byways on his path to publication.

Ollmann aims to be more truthful still. And though he admits to preferring a Herzogian notion of “poetic truth,” the book is surprisingly free of incident, despite his subject’s adventurous life. Though Seabrook was, for example, frank about his passion for sadomasochism, Ollmann claims that he hasn’t written a book for lovers of S&M or of any of his protagonist’s other eccentricities. “Cannibal enthusiasts, save your letters,” he writes in his preface. We regularly glimpse half-naked women chained to bannisters and hanging (willingly, apparently) from the rafters, but we see them as his three wives apparently did: more like occasional, incidental decorations than as the centerpieces of his story. Given how central these details are to Seabrook’s appeal, one sometimes wonders what drew the accomplished cartoonist Ollmann — who reportedly spent a decade preparing the volume — to his subject in the first place.

Though Ollmann claims it was Seabrook’s frankness that lured him, it’s possible he simply wants us to go back and read the originals that inspired his own story. Those who come away intrigued will find plenty to guide them: the clearest indications of Ollman’s own critical opinions emerge from the connoisseurish way he stacks Seabrook’s books up against one another. His love for these volumes is clear. Why else would he conclude his narrative with Seabrook’s own words: “If nobody reads you after you are dead, your words are dead, but if some living people continue to read your words, your words remain alive.” In this sense, we might understand Ollmann’s elisions as a kind of necromancy, an attempt to resurrect volumes long since buried on the shelves of collectors.

Ollmann sustains his lack of interest in spectacular incident throughout his book’s 300-odd pages. Consider, for example, his approach to the experience that helped Seabrook break into the journalistic big leagues: a parachute-free leap from a hot air balloon. Ollmann refrains almost entirely from depicting the dive, or even describing what it entailed, dwelling instead on the manic moment of inspiration before and the meteoric rise after. He treats Seabrook’s interpersonal peculiarities with a comparable insouciance, as when he offhandedly shows the writer leaving his wife for a woman married to a man who would go on to marry Seabrook’s own wife.

Ollmann’s book, that is, doesn’t totally avoid these marquee-ready moments. It simply resists their allure. In the process, it dries them out a bit, turning steaks into beef jerky. There’s merit to such a method, much as there’s nutrition to be found in cured meat. Seabrook is never a dull read, and it consistently engages. Nevertheless, it’s uncommonly willing to render its subject dull.

If you flip through the book, you soon realize that this is a deliberate choice. Throughout, Ollmann draws in a fittingly jittery style, every line anticipating the alcoholic collapse that would eventually doom Seabrook. Without fail, though, Ollmann attends obsessively to his subject, placing him at the center of almost every panel. It’s all but impossible to imagine a narrative film fixating on its protagonist’s features as often or as long as Mr. Seabrook does. Seabrook’s is a face that we come to know from every angle, each subsequent image a slowly accumulating study in dissolution. Though Ollmann claims he doesn’t intend to make some biographical argument, his indifference to the potentially enticing narrative elements of Seabrook’s life allows us to see another story in the spread of the protagonist’s wrinkles and crags. We eventually come to view Seabrook as he must have viewed himself: caught in an endless circuit of monomaniacal self-regard and morose self-loathing.

If this approach sometimes threatens to take a complex man and make him boring, it ultimately serves to de-exoticize Seabrook, as if to anticipatorily inveigh against the concern that he cannot have been real. It’s a fitting sleight of hand, in part because it aligns so well with Seabrook’s own ideals. Ollmann’s Seabrook is a kind of amateur anthropologist, as in a different way Ollmann himself is: like an anthropologist, he is interested in the way Seabrook lived every day, not in the unusual incidents that made his life exciting.

Though this approach is sometimes maddening, it also marks Ollmann’s greatest accomplishment as a biographer. Following Ollmann through Seabrook’s life — mostly in chronological order, rarely sticking with any one narrative detail for too long — feels a bit like getting a tour of Washington, DC, from a crew of locals who keeps forgetting that visitors may not have seen the White House before. It’s there, yes, but they’d rather take you to the sandwich shop they visit on their lunch breaks. In the end, you might be frustrated, but you realize that your frustration is counterbalanced by a knowledge that feels deeper for its focus on the quotidian rather than the spectacular.

In this, too, Ollmann may be drawing inspiration from Seabrook, who struggled, Ollmann tells us, against the imperative to sensationalize his subjects even as his highest ambition was going native. For all its problematic dimensions, this ambition engendered, in Ollmann’s telling, an openness to experience that makes the journalist uncommonly sympathetic, even in unsympathetic situations. It’s an impulse we see most clearly in a rare flash-forward at the start of Ollmann’s section on Seabrook’s time in Haiti. This scene, which repeats at the section’s close, depicts the journalist standing before a shrine, entreating “Papa Legba, Maîtress Ezilée, and the Serpent” to let him do justice to the people who’ve trusted him. “Protect me from misrepresenting these people and give me the power to write honestly of their mysterious religion,” he says, arms spread, shirt hanging open.

Seabrook himself would gradually betray these principles, fame and fortune proving as fatal as any cocktail. Ollmann, to his great and unlikely credit, succeeds where the man he memorializes failed.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jacob Brogan is a journalist and critic based in Washington, DC. He holds a PhD in English literature from Cornell University. His work appears in Slate, Smithsonian, The New Yorker, and other publications.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Skip the Words, Read the Pictures

Jonathan Shapiro on Edward Sorel's "Mary Astor's Purple Diary."

“I Haven’t Talked Much About Her Films”: Edward Sorel’s Mary Astor

Christina Newland on Edward Sorel's new biography of Mary Astor.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!