The Content House: On Bo Burnham’s “Inside” and “The Inside Outtakes”

Sophia Stewart thinks about the relationship between art and content through Bo Burnham’s twin specials, “Inside” and “The Inside Outtakes.”

By Sophia StewartFebruary 22, 2023

ON A RECENT trip home to Los Angeles, I decided to make a pilgrimage to 1428 North Genesee Avenue. Tucked away on a quiet street off Sunset Boulevard, 1428 North Genesee is a two-story Dutch Colonial home built in 1919. It has white paneling and a green roof, three bedrooms and three-and-a-half bathrooms. Manicured shrubs and columnar trees form a protective barrier around the front yard; in the backyard is a pool and a detached guesthouse. In January 2022, the house sold for $2.98 million. The sale was covered widely by the media: 1428 North Genesee played a prominent role in the 1984 film A Nightmare on Elm Street and its sequels, providing the exterior for the primary suburban home haunted by Freddy Krueger. What most reports of the sale left out was the identity of the previous homeowner, filmmaker Lorene Scafaria, who had lived there with her partner, the comedian Bo Burnham, and it was there that Burnham wrote, performed, filmed, and edited his 2021 musical special Inside.

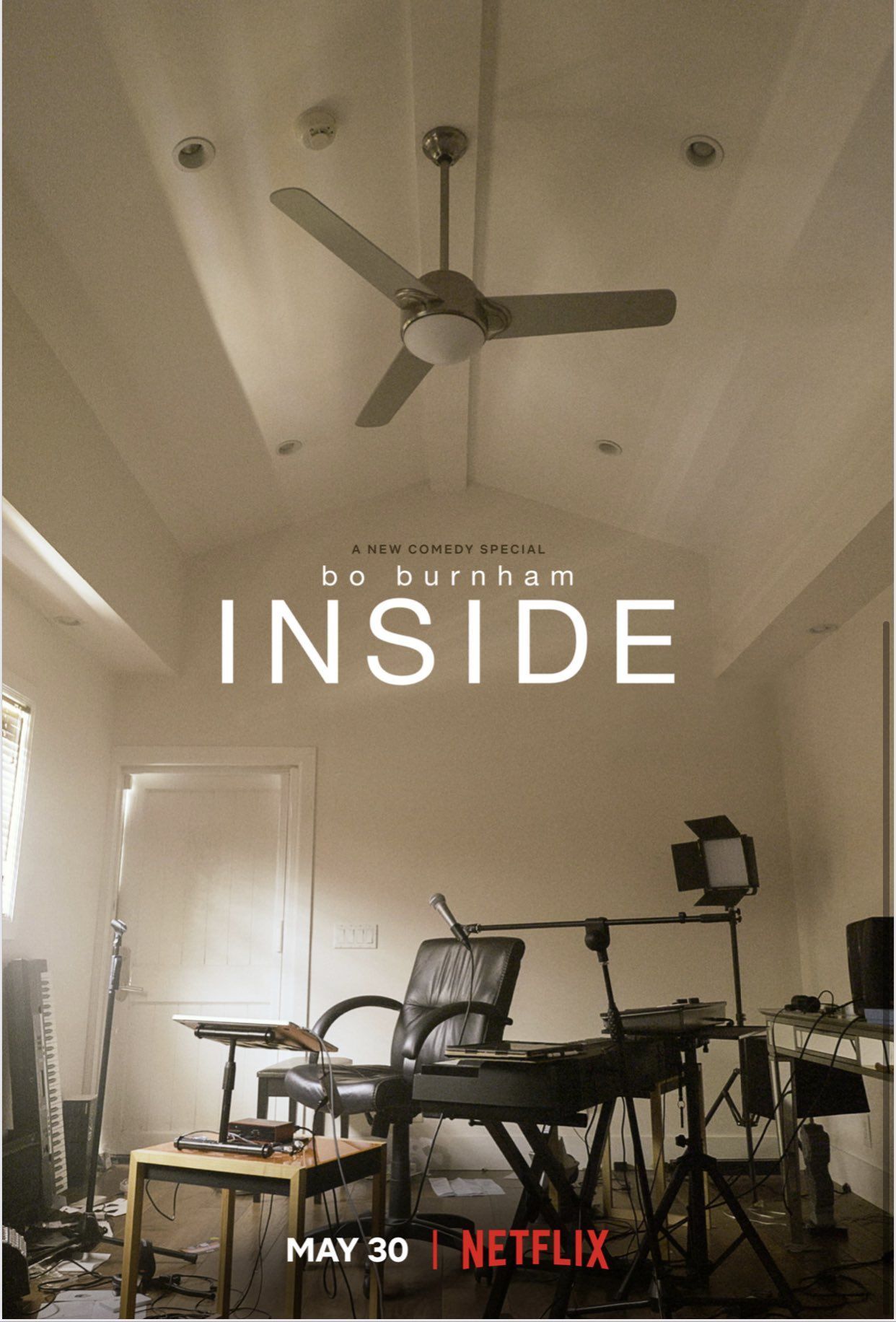

Burnham spends the entirety of the special “inside” the one-room guesthouse of 1428 North Genesee. That’s sort of the whole gimmick, the implication being that, because of the pandemic and its attendant lockdowns, he can’t leave. (The opening song, “Content,” is about being “locked inside of my home.”) But over the course of Inside, it becomes increasingly clear that while the pandemic may have sent Burnham to the guesthouse, it isn’t what keeps him there.

I wanted to see 1428 North Genesee for the same reason one might go see Finca Vigía or Shaw’s Corner or La Casa Azul: I was drawn to this place that I felt had gestated genius. My admiration tallied with the critical consensus; upon its release, Inside was met with near universal acclaim, though critics diverged on exactly why they found it so good. For some, the film is a pandemic-era time capsule; for others — mostly those of us who, like Burnham, grew up with and on the internet — it isn’t so much about a moment in time as a way of life. Most of the songs in Inside are about feeling trapped or alienated in ways that far predate the pandemic: the sense of estrangement FaceTiming with one’s parents, the disembodied sterility of sexting, the unending abyss of the internet, the existential anguish of bearing witness to climate change and mass culture in decline. The pandemic is the inciting incident but not the whole story.

The story of Inside is bound up with the 1428 North Genesee guesthouse, that room where life and work and art and content converge. As the special unfolds, Burnham’s self-exile appears more cowardly than compulsory. There’s no mandate from Los Angeles County preventing him from leaving the guesthouse. “If I finish this special, that means that I have to not work on it anymore. And that means I have to just live my life,” he says in the final third of the special. “And so, I’m not gonna do that, and I’m gonna not finish the special. I’m gonna work on it forever, I think.” His isolation, the longer it drags on, seems less a consequence of COVID-19 than a choice to cede life to art.

He gives us sporadic updates as to how long he’s been at work on this thing: a month, six months, a year. He decides to give himself until his 30th birthday to finish. His 30th birthday comes and goes. His hair grows long; he sprouts a beard. The guesthouse, spotless in the special’s opening shot, becomes overrun with wires and lights and instruments. He starts to look haggard. He sleeps on the futon, brushes his teeth in the kitchen sink. At one point, he’s so deflated that he delivers his stand-up lying down on the floor, surrounded by a tangle of cords.

It’s all very sad and romantic, the tortured recluse giving everything to his art. Yet we know from Burnham’s previous special, 2016’s Make Happy, that hearth and home are waiting just outside the guesthouse door. Make Happy ends with Burnham sitting in the guesthouse, in the dark and at the piano, plucking out a final tune. Eventually he gets up and opens the door onto a heavenly yard, where Scafaria and dog Bruce are waiting for him on the back porch of the main house. He crosses the lawn to join them. So when Burnham sings about being “stuck in a room” during Inside, I want to shout at him, Just open the fucking door! Then I remember he’s not really talking about the guesthouse.

In the song “Look Who’s Inside Again,” Burnham describes himself as having been “a kid who was stuck in his room.” Here, “stuck” refers not to a sense of banishment but refuge: his room was where he felt safest, most himself, free to play his music and write his jokes. The pandemic hasn’t imposed on him unprecedented isolation; it’s enabled a deep-seated behavior — one that feels distinct to Burnham’s and my generation. In one segment, Burnham sings about the feeling of having “the whole world at your fingertips, the ocean at your door.” Yes, of course we want to stay inside our screens inside our work inside our heads inside our art inside our guesthouse.

¤

In 2022, Burnham released The Inside Outtakes, an hour of unused material: songs, bits, and interludes left on the cutting-room floor, along with behind-the-scenes footage. In Outtakes, Burnham undermines any of the artistic mystique he created in Inside. He acknowledges, for instance, that his stay in the guesthouse is entirely voluntary. He wistfully recalls a time “before I locked myself in this room and lost my mind.” In another cut interlude, he holds a camera to his crotch and manually adjusts the Zoom to look like he’s jerking off, a nod at the fact that his confinement — and the art it’s produced — is masturbatory, a way to make himself feel good.

Getting to see what Burnham left out of the final cut prompts auteurist speculation: Why didn’t this song or that bit make the cut? Why did he tweak that lyric, that melody, that camera angle? Most of the songs that he ended up excising have all the hallmarks of a great Burnham number, namely ironically interrelated form and content. (In Inside, a cozy campfire tune about existential dread, a folk song in the style of “Sixteen Tons,” about unpaid internships; in Outtakes, a Drake-esque track about the ennui of a long-term relationship, a trap song, complete with a hype man, about the tedium of microwaving popcorn.) These are the kinds of decisions that no amount of technical expertise can account for, that artists usually keep private — that would, in other words, stay in the guesthouse.

At several points in Outtakes, Burnham shows us every take he recorded of a single song, simultaneously filling the screen like tiles, sometimes dozens at a time. Some feature different camera angles or different lyrical choices; one by one, all but one cut out and disappear as he inevitably fucks up each of the other takes. Outtakes even undermines some of Inside’s more vulnerable moments. That Inside scene featuring him telling jokes while lying on the floor amid that tangle of cords, for instance — in Outtakes, he shows us how carefully he’s arranged the shot composition, lifting his head from the pillow to check the video monitor over and over, ensuring that everything is exactly as he wants it.

¤

Bo Burnham’s website, until it was redesigned in late 2019, used to have a page called “THINGS.” At the top of the page, Burnham wrote, “This is where I post things that I think are really great.” Among them were Ruben Östlund’s uncomfortable film Force Majeure (2014), David Foster Wallace’s story collection Brief Interviews with Hideous Men (1999), and Radiohead’s song “Present Tense” (2016). Also prominently featured: Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s 1984 musical Sunday in the Park with George.

Viewed through the lens of Burnham’s affinity for Sunday, the diptych of Inside and The Inside Outtakes takes on deeper resonance. The Pulitzer-winning musical tells the story of painter Georges Seurat, who is at work on what would become his pointillist masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. In the first act, he holes up at home for long stretches, refusing to leave until he’s finished the painting — specifically, the intricate hat that one of the painting’s subjects is wearing. “How you watch the rest of the world / From a window,” he laments, “While you finish the hat.” His lover, Dot, waits around for him to join her in the real world. But, like Burnham, Georges is “stuck in his room,” and it’s no one’s fault but his own. By Act II, which takes place a century later, Georges’s suffering has been vindicated by the fact that it produced a masterpiece. At this point, the musical turns its focus from process to production: once you’ve dedicated yourself to your vision, what is required to bring it to life? “Art isn’t easy,” declares one character. “The art of making art is putting it together.”

If Inside is about watching the rest of the world from a window, then Outtakes is about making art. Outtakes reminds us that this act isn’t an inherently noble endeavor. In fact, Outtakes frames the making of Inside as an avoidant and solipsistic endeavor, born out of fear.

At one point in Outtakes, Burnham revisits the most striking moment from Inside’s opening song, in which he shines a headlamp on a spinning disco ball to create a kaleidoscopic light show. Outtakes reveals what went into that choice. “Is this fucking doing anything?” he groans to himself as he spins the disco ball in his hands and tries shining the headlamp on it from different angles. “Is this looking cool or just fucking stupid?” We relish knowing, in a bit of dramatic irony, that it does in fact look cool. We watch Burnham fumble for a long time: months into filming, he still felt he had “nothing usable.” Most days, he says, it “feels like I’m staying busy and it’s been fun. And then, other days, like today, I just feel like I’m completely spinning my wheels and wasting my time and I’ve now committed myself to never finishing this thing and just being in this room until I fucking …” He trails off.

¤

I was a teenager when I first learned about “content houses” — residential homes where YouTube (and, later, TikTok) creators could cohabitate and collaborate in a total melding of life and performance. It was the 2010s, and these houses had begun to spread like a blight on the hills of Los Angeles, a short distance from my own home. Part dorm, part art colony, content houses are opulent and densely peopled, every room equipped with ring lights and tripods. At the time, I thought they were a fad. My dismissal softened into ambivalence as the years went on and the public and the private, the personal and the professional, blurred together in my own life. By the time the pandemic institutionalized working from home, content houses felt less like a craze than an omen.

The Genesee guesthouse is spartan and Burnham its only resident, but for the year that he lived there, it functioned not unlike a content house, outfitted as a film set first and a domestic space second — a place intended not for living but for making. “The outside world, the non-digital world, is merely a theatrical space,” Burnham says at one point, “in which one stages and records content for the much more real, much more vital digital space.”

This word “content” is new to Burnham’s comedic vocabulary. His work has always been about performance, but in the context of either art or entertainment. In his 2010 special Words Words Words, he declares shamefully, “I am an artist […] a self-centered artist,” and implores us, “Please don’t revere me […] please don’t respect me.” Later, in Make Happy, he assumes the mantle of “entertainer,” this time telling the audience, “If I stop entertaining you, throw me to the curb.” In Inside, he aligns himself with the content-creator. “Thank you for watching my content,” he says during a vlog-style interlude. He holds a knife as he asks us to stay tuned, a stance that is threatening and desperate. “As you guys know, I work really hard to try to bring you guys high-quality content that I think you’ll enjoy.” His words, drenched in irony, gesture at the increasingly blurry distinction between art, entertainment, and content.

If art is characterized by craftsmanship, then content is characterized by churn, produced through what Burnham calls a “content-industrial complex.” Burnham isn’t just a veteran of the content-industrial complex; he’s one of its greatest success stories. At 16, Burnham began posting videos to then-nascent YouTube of himself, in his room, playing songs he had written. His compositions were catchy and clever, though juvenile in their humor. “I started doing comedy when I was just a sheltered kid / I wrote offensive shit, and I said it,” he admits in Inside as he watches projections of his teenaged self on YouTube. His videos quickly went viral (as of June 2022, they have amassed more than 600 million views) and launched his comedy career. Within a year, he had signed a four-record deal with Comedy Central. At 25, he had released three specials, two of them produced by Netflix. By the time he began work on Inside, he had been churning out performances, albums, scripts, and films for nearly 15 years.

In 2016, Burnham stopped performing live due to a panic disorder. At the beginning of Inside, he apologizes for his absence — he’s “been a little depressed” — and says he has recommitted himself to his work. “Look, I made you some content,” he sings. “Daddy made you your favorite / Open wide / Here comes the content.” Here he acknowledges his creative labor — “I made you some content” — but by labeling its fruits as “content” rather than art, he downplays both his level of craft and his depth of feeling. Open wide: content is meant to be consumed, the more indiscriminately the better.

Throughout Inside, he borrows the visual language of digital content. Between songs, he mimics YouTube reaction videos and Twitch-style streaming. At one point he recreates one of vlogging’s most consistent conventions: the wake-up shot. We see him lying on the futon, apparently asleep, fluttering his eyes open in the soft morning light. We know that getting such a shot requires waking up offscreen, setting up a shot at your bedside, getting back under the covers, pretending to sleep, and reenacting the first moments of your morning for the camera. We suspend our disbelief anyway. Yet, in both Inside and Outtakes, Burnham also occasionally draws our attention to the constructedness of what we’re seeing. We see him testing lighting options, erecting sets, editing in GarageBand, playing with camera angles. We see his smoke machine, his ring light, his in-ear monitors — all intermittent reminders to take nothing for granted.

Toward the end of Inside, Burnham films himself talking in the mirror: “I am not feeling good,” he says before he breaks into heaving sobs. Meanwhile the camera, set on a tripod, zooms in on itself in the mirror. Is he really crying? Is this an act of mimesis, like the wake-up shot? Or just a straight-up fabrication? Well, we know two things. First, in all his work, Burnham’s “I” is slippery. We know, for instance, that he’s been with Scafaria since 2013 and likely doesn’t spend night after night (as he sings) “sitting alone / one hand on my dick / and one hand on my phone.” We also know that Burnham’s primary modes have always been polish and precision. “My show is very planned,” he says in Make Happy, “to the word […] to the gesture.”

Inside the guesthouse, performance and authenticity are strange bedfellows. Burnham performs being “stuck” in the guesthouse, but his stuckness isn’t inauthentic. Burnham can’t bring himself to leave. What’s the difference? The result is the same.

¤

I took breaks to scroll through Twitter while writing this essay. I scrolled and scrolled and scrolled, my feed refreshing seemingly infinitely — I was not looking for anything in particular, just some opportunity or announcement or joke that would make my life more tolerable, change it for good. I tell myself and others that I have no choice but to use Twitter for work. I can’t leave, I say, and I hate it. It’s a hellsite, a guesthouse. Not a lie, a performance.

Another performance: I wouldn’t work so much if I didn’t have bills to pay. My recent trip home to Los Angeles was partly at the behest of my mother, who felt I needed a break from my work. The city’s expensive, I tell her over FaceTime, hunched at my desk. This is true; working like I do is how I’m able to pay my bills. But I don’t think about financial necessity: I am working, and I am also indulging in all the deprivation that comes with it. If I were to tell her that I can’t bring myself to work any less, that I don’t want to work any less, what would she say? Would she want me to just open the fucking door?

Eventually, offscreen, Burnham leaves his guesthouse. He opens the door. A few days after the release of Inside, he tweeted a photo of himself in what appears to be the Genesee backyard, the sun emoji for a caption. He’s made it outside, no longer watching the rest of the world from a window. He’s finished the hat. In the photo, we see the right half of his contented face, a lush green tree, a cloudless blue sky. I stood under this same patch of sky when I paid my visit to 1428 North Genesee, just over a year later. It looked like any other house. The guesthouse was hidden from view.

¤

Sophia Stewart is an editor and writer from Los Angeles. She lives in Brooklyn.

LARB Contributor

Sophia Stewart is a writer, editor, and cultural critic from Los Angeles. You can find her writing here and follow her on Twitter @smswrites.

LARB Staff Recommendations

When Reality Isn’t: On Nathan Fielder’s “The Rehearsal”

Israel Daramola reviews Nathan Fielder’s “The Rehearsal.”

French Cigarettes and a Lot of Coffee: On Skye C. Cleary’s “How to Be Authentic”

Graham weighs the existence, and not the essence, of Cleary’s latest book on how to be authentic by Beauvoir’s measure.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!