The College Writing Center in Times of Crisis

Genie N. Giaimo explores the need for more comprehensive guidance for writing centers during various crises of late-stage capitalism.

By Genie N. GiaimoFebruary 13, 2024

WRITING CAN BE a lonely undertaking. As a professor of writing and rhetoric, I often think about what leads us to produce and avoid. We avoid writing because we want to avoid pain and discomfort. Yet because writing is a mainstay of our work and our promotion process, we feel like we should simply be good writers.

This is the paradox of academic writers and writing: we are compelled to write even as we struggle to. Here, I am reminded of an oft-circulated quote on the “ease” of writing by author Gene Fowler: “Writing is easy. All you do is stare at a blank sheet of paper until drops of blood form on your forehead.” In my work as a writing center director, I have observed people willing to trade blood for words, were it that “easy” …

But as many of us know, writing isn’t easy. I have worked with professors who become physically ill before they start a writing project. Their bodies tense. Their stomachs churn. They do every ancillary task (and several unrelated ones) to avoid sitting down at their desks. Some academics have disclosed to me their related disabilities and shame that they cannot produce error-free writing. Others recount horror stories about advisors berating their writing in large lab meetings. Many tell me they hate writing. Many more have paid thousands of dollars for writing coaches, productivity consultants, copyeditors, and other costly services. In sum: For many academics, writing is not only lonely; it is also profoundly stressful, traumatic, and expensive.

Writing centers are often a college’s best-kept secret. Those who attend regularly benefit through better grades, higher self-confidence, lower drop-out rates, and deeper community embeddedness. Those who do not utilize them have more stochastic academic results.

In colleges and universities across the United States and around the world, writing centers try to find joy in this often-bemoaned mainstay of academic work for faculty and students alike. There are few places, I often tell my co-workers and advisees, where a group of trained and kind experts will engage with not only your writing but also your ideas. There are also few places, as I have observed in my 12 years as a director, that engage so directly—and in so many vital, various ways—with crisis.

¤

To outsiders, writing centers are at once unassuming and mystifying. A room or series of rooms in an academic building or library, they are often viewed as mundane educational spaces. But, much like teaching, what goes on in them can be magical (and not just for academic outcomes). On any given day, a writer might come in wanting to workshop a National Science Foundation grant, or a lesson plan, or a medical school personal essay. On any given day, a tutor might work with an adult learner, an international student, a veteran, and a postdoctoral researcher. The variety is constant and extends to need: revision, editing, working through feedback, developing healthy writing practices, undoing procrastination, unlearning writing anxiety and low confidence. And even the most mundane of these exchanges can produce paradigm-shifting experiences for writers and tutors.

Yet writing centers, at their core, were created during times of crisis. Only, the crisis then was about “unprepared” students rather than the myriad challenges we face in higher education today.

The history of writing centers runs in parallel with the history of higher education in the United States. They have been around in one form or another for over 100 years. Introduced first as writing labs or clinics, their creation was a response to enrollment pressures, underprepared students, and the limitations of lecture-style education models. For decades, students enrolled in a writing lab or clinic much as they would any other for-credit course. They engaged in drills to reinforce grammar and writing. These labs could have upwards of 75 students in each section and be facilitated by one instructor; composition scholar Neal Lerner describes them as boring students to tears and portrays the instructor as a “circus ringmaster.” In other words, these earliest incarnations of writing centers were—as they seemed to have always been—underfunded sites where the work of learning how to write was outsourced to more precarious educators.

With successive expansions of higher education to include more and diverse students (first rural students and women at the turn of the 20th century, followed by the children of immigrants in the 1930s; veterans returning from WWII; and new immigrants, people of color, and working-class students in the 1960s and ’70s), writing centers supported students who were unable, by university standards, to write. This remedial model continued through the open access education movement of the late 1960s, though explicit references to “writing centers” disappeared from scholarly conversations as the fields of rhetoric and composition gained traction. From the 1970s onward, we have seen more homogeneity in the kind of writing center operated by colleges—a format more akin to what I describe above than to a clinic or a lab of the early 1900s. Ever since, writing centers have been staffed mainly by peer tutors.

Today, writing centers are far more complex in both structure and service, though they still tend to be a hub for BIPOC and underrepresented students on college campuses. At one time, this service was meant to force such students into compliance with a standard academic English; now, we focus on building confidence, skills, and metacognition. The process of writing matters more than the correctness of the final product—though, especially for students who hail from underserved backgrounds and who hunger for explicit instruction in writing, that matters too. Writers of all levels and expertise use them, and the work that is done is far more curated and complex: skills and drills have largely disappeared from our practices, as have handouts, quizzes, and clinics. A lot of what takes place in a session might look more like writing-focused therapy than it does a lesson on grammar.

In these sessions, students ask:

“Why can’t I complete a project on time?”

“Why can’t I enjoy writing like I used to?”

“How can I become a more productive writer?”

With rising mental health issues among young people, such concerns arise in the writing center in ways that are far less diagnostic (i.e., find the problem and solve it) and far more socially oriented and supportive (i.e., train tutors to cross-refer writers, but also support tutors through community care practices). In light of this history and ongoing need, it can be frustrating when, because of the physical structure of writing centers—and how students “use” the space—scholars in our field wonder if our workspaces are too much like “cozy homes.” Living rooms, familial spaces, and brightly lit rooms filled with plants all might seem terribly bourgeois—and the fact that the majority of people who direct writing centers (estimated to be between 71 and 80 percent) are white women doesn’t help this framing.

¤

Yet far from mere “cozy” living rooms, writing centers are disrupted by events that happen within them and outside them. What happens to our space and our community when we need to shelter in place because of an active shooter, for example? In my book Unwell Writing Centers: Searching for Wellness in Neoliberal Educational Institutions and Beyond (2023), I argue that the work we do can seem so fun and empowering—especially to student writers—that the very real toll and emotional demands it has on peer tutors often goes overlooked. As every new school shooting, student death, or other emergency shows us, crises are pervasive in higher education. And, because of how interconnected writing centers are to the larger campus community, these crises affect our spaces profoundly. Tutors are often, after all, students, so they carry all the experiences that students have on a college campus into the writing center—and their work.

In part, I wrote my book because I experienced several crises at my workplaces (gas leaks, terrorist warnings, active aggressors, weather emergencies), and there was almost no research or training on how to handle these situations. Yet this training is especially important in writing centers, which are physical spaces where groups of students routinely gather. I wanted to prepare people who, like me, would become writing center directors responsible for dozens, if not hundreds, of student workers. And after crises (or sometimes before), tutors would look to me for answers, and I would come up blank. How should a tutor handle an inebriated student during a tutoring session? What would happen if a student propositioned a tutor? What should we do if a blizzard or tornado or flood impacted our commute to work?

In the wake of an active aggressor situation where tutors, students, and I huddled in our writing center for over four hours during campus lockdown, I decided to assess how campus and other tragedies impact writing center workers. We know that academic workers are impacted by crises in our communities. For example, during the lockdown, our ability to work with writers was obviously hampered; additionally, international tutors tried to enter campus for their shifts because they did not fully understand “run, hide, fight.” But up to that point, little attention had been paid to the impacts that crises have on academic workers—particularly undergraduate and graduate students.

¤

I have found that—as with many mental health concerns among younger people today—crises are a mixed bag. Some tutors were deeply impacted by student deaths on campus; others were not. Some reported feeling profoundly unsafe after Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential election because of the increase in hate speech and racist attacks. Others were more affected by everyday stressors in their work, such as feeling unable to manage the responsibilities entailed by working multiple jobs, or encountering a student who would not accept their writing feedback.

Stress, in this way, is complex, and is often located at a nexus of needs like financial, physical, and emotional stability. Yet long-term stress has deleterious effects on one’s memory, cognition, and resilience. The critical skills and behaviors needed to engage in the learning process are adversely impacted by high levels of stress. Students in the throes of mental health crises struggle not only with academic performance but also with the day-to-day meaning-making that might otherwise arise from self-reflection and introspection. Stress can crash our learning—and writing—systems; it can also hinder our emotional and intellectual growth.

Of course, writing centers often play an important part in mitigating these and other kinds of student stressors around academic performance and learning anxiety. For tutors, writing centers can provide necessary mentorship and advice that improve retention and persistence. In fact, writing centers can help all kinds of students—those who seek writing support and those who provide it—find community on campus and be more likely to remain in school.

At the same time, peer tutors need preparation and training for doing work that verges on crisis response and requires supreme interpersonal skills and training. After all, students carry their personal traumas into their writing, which means that these issues will often emerge in tutorials. I once worked with a doctoral student frantically trying to complete her dissertation after experiencing a complicated, dangerous childbirth and postpartum depression. Her (STEM) department was cutting off funding at the end of the semester. As a graduate student on the academic job market, I commiserated with the writer over funding limits and talked about a recent devastating running injury that was hindering my ability to revise my own dissertation. We waited for her to finish crying before turning to her writing. During the early days of the pandemic, online writing support might have been one of the only contact points for both student writers and tutors, given the sudden departures from campuses and the move to online and even asynchronous writing.

¤

As the COVID-19 pandemic showed us, academics aren’t fully prepared for crisis or what comes after. Researchers have written about the burnout issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic as well as faculty and staff who are headed for the exit because academic work has become unsustainable. Especially among professors—not to mention workers in other care-based professions like the medical field or K–12 education—burnout has become a major issue, and it is related to the increasingly complex and expanding work-related duties. We have become, among other things, trauma responders, life coaches, and mental health–adjacent support. During the pandemic, we were asked to expand our teaching capacity to suit all kinds of online learning models, as well as make ourselves available and flexible for students. Few administrators, however, asked what they could do to support our mental health. In the unidirectional customer-based model of higher education, faculty and staff roles expand to include all kinds of novel tasks, even as hiring tenure-track faculty steeply declines.

Elsewhere, I write about the neoliberal university and the ways it shapes everything that we academics (including writing center directors) do—from the way we staff our centers using peer labor to the ways we overwork ourselves in profoundly contingent positions. The neoliberal university encourages job creep, overwork, and deskilling, all of which are harmful to our community that is comprised of workers and students alike.

This “just in time” model of higher education also often fails spectacularly when faced with crisis. Running institutions at the bare minimum while overrelying on tuition dollars and contingent staffing means that when crises—like the Great Recession, the COVID-19 pandemic and its global economic fallout, climate disasters, mental health crises, or gun violence—strike, the institution struggles to respond. And when it does, it overrelies on already-overtaxed workers to marshal that response.

Peer tutors—who are also affected by the alarming rise in mental health crises among college students—carry extra care burdens that are frequently unanticipated and that, until recently, we have not trained them to provide. Perhaps this is because we are only now coming to terms with the disastrous effects of late-stage capitalism—climate change, financial insecurity, and increased “deaths of despair,” among others. Perhaps this is because the changing landscape of higher education has fundamentally shifted academic work—even student academic work.

I focus my research on tutor well-being more than student well-being (though tutors and students often overlap in both identity and community). I do this for several reasons: it is less discussed, it is pertinent to being a progressive workplace, it is hard to retain trained workers, and it is our obligation to prepare tutors for the realities of teaching writing in the 21st century. Stress, anxiety, crisis—all are likely to arise in and around the center. I have worked my entire career to prepare tutors, and, of course, that preparation now looks prescient. But even before the pandemic, students were struggling with mental health and other challenges. Now, with the acceleration of neoliberal crises, coupled with other dramatic changes to our world that include AI writing, the pandemic-induced learning gap, and any number of existential crises that humanity faces, it is almost criminal for us not to respond as we confront these issues, sometimes on a daily basis.

¤

Make no mistake: I have also witnessed the joy of writing through the writing center. I have mentored and worked alongside half a dozen faculty for several years—and through the early stages of the pandemic—in a writing group that yielded dozens of publications, cross-disciplinary collaborations, and long-term friendships. I have watched advanced writers return, again and again, to the writing center to work on the burning questions of their careers, such as how to support sex workers through nonpunitive rehabilitation services, or how to support international students’ English language learning, or how to identify new species in the rainforest. I have watched first-year students cry with relief after finally starting a writing project in a tutoring session. I have watched peer and professional writing tutors work through the affective and metacognitive challenges of both their own writing and their tutoring work.

Life often happens in and around writing centers. In many cases, tutors work several years in writing centers—much longer than we might expect from a student’s first job at college—and they create bonds that last long after they graduate and move into careers. They date one another and even get married. They disagree with one another. They collaborate with and uplift each other. They also hang around in the writing center. A lot. They do their homework and eat their meals in the center. Sometimes, they take naps there before work and class. Throughout all of this, I have watched tutors grow. They’ve graduated and taken jobs as teachers, computer programmers, nurses, architects, professors, and lawyers.

Writing can be a lonely, stressful process. Writing centers mitigate such issues. They also propagate community—and joy.

So, my charge here is fairly straightforward: higher education should invest more in things that we already know have a deep impact and help students not only to finish their degree but also to flourish while doing so. Invest in livable wages for staff and faculty, quality mental health and academic support services, and programs that build intentional communities of practice. For those in—and outside—higher education, talk more about writing, do more writing, and share your writing with others. As we see in writing centers, writing (doing it, discussing it, reworking it) is the glue that makes up a community—talking with others about one’s ideas and one’s writing process can open up new levels of cognition and engagement that might otherwise be unobtainable. And, in a world where we are less well than perhaps even a few years ago, writing can save our shared humanity; it can bring us together rather than tear us apart.

¤

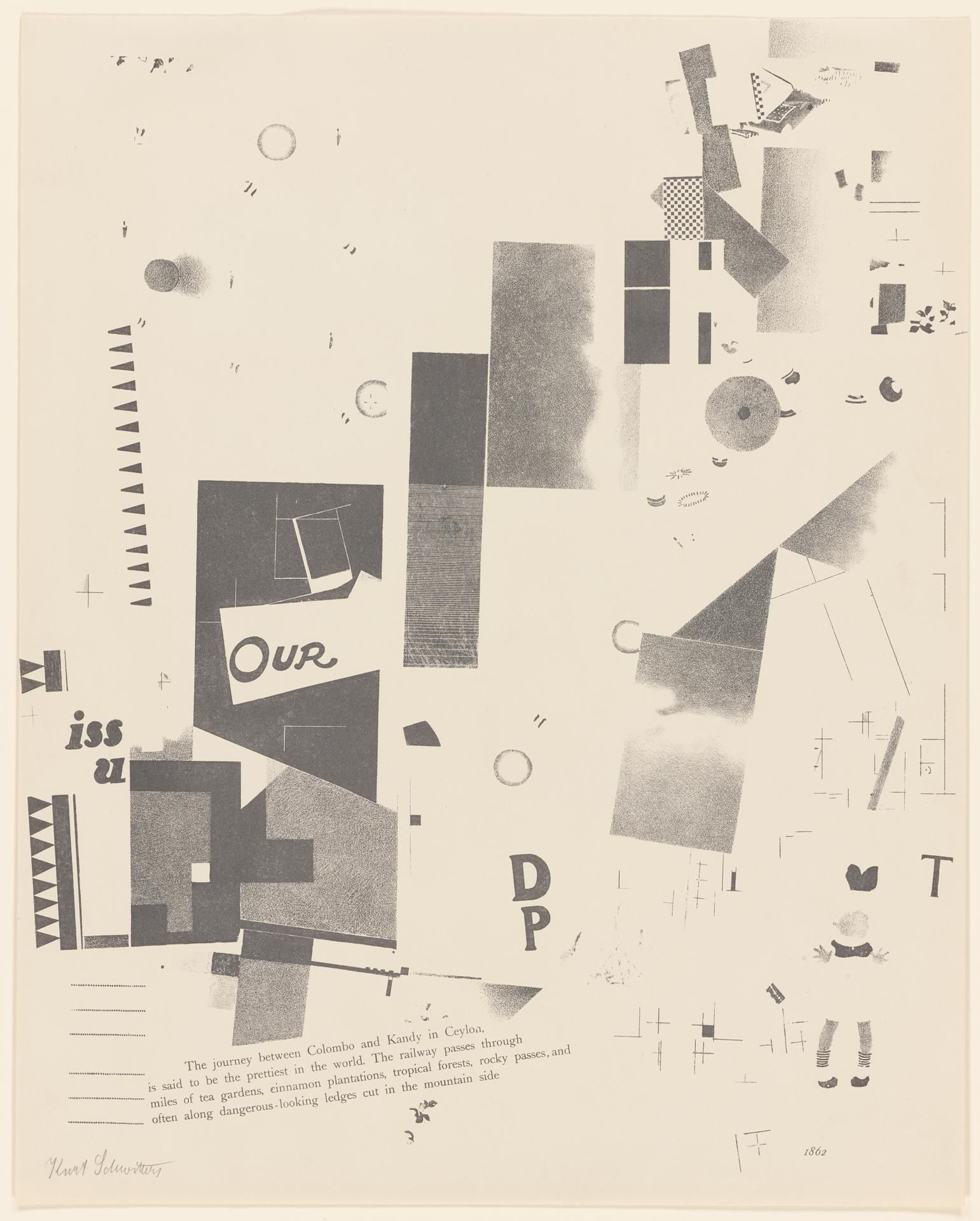

Featured image: Kurt Schwitters. Untitled, no. 6 of 6 from the portfolio Merz 3. Kurt Schwitters 6 Lithos. Merz Mappe. Erste Mappe des Merzverlages, 1923. Gift of the Estate of Katherine S. Dreier. Yale University Art Gallery (1953.6.227g). CC0. Accessed February 9, 2024.

LARB Contributor

Genie Giaimo is an assistant professor of writing and rhetoric at Middlebury College. She is the author of Unwell Writing Centers: Searching for Wellness in Neoliberal Educational Institutions and Beyond (Utah State UP, 2023) and two edited collections— Wellness and Care in Writing Center Work (2021) and, with Megan O’Neill, Writing Assessment at Small Liberal Arts Colleges (forthcoming, 2024). She is currently working on a new project about how academic workers navigate chronic illness and disability in the academy.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Is It Possible to Teach Anti-Capitalism? On James Rushing Daniel’s “Toward an Anti-Capitalist Composition”

Ryan Boyd reviews James Rushing Daniels’s “Toward an Anti-Capitalist Composition.”

We Other Humanists: On Paul Reitter and Chad Wellmon’s “Permanent Crisis: The Humanities in a Disenchanted Age”

“Crisis” is both the driving force and the false consciousness of the humanities.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!