The Body Keeps the Record: On Julian K. Jarboe’s “Everyone on the Moon is Essential Personnel”

The altered (and dynamic) body serves many purposes in Julian K. Jarboe’s “Everyone on the Moon Is Essential Personnel.”

By Sara RauchApril 18, 2020

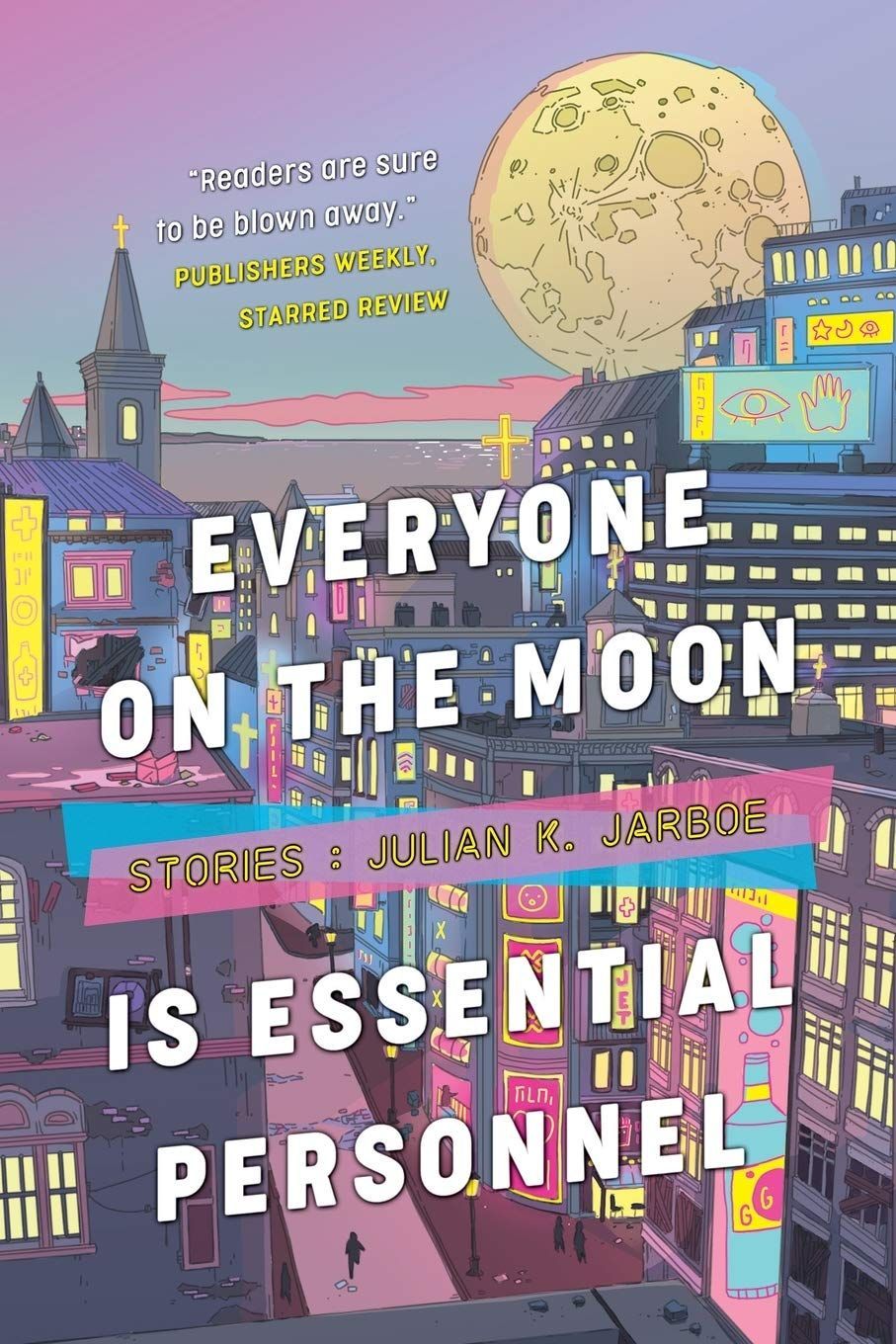

Everyone on the Moon is Essential Personnel by Julian K. Jarboe. Lethe Press. 222 pages.

IN “I AM A BEAUTIFUL BUG!,” the penultimate piece in Julian K. Jarboe’s excellent debut story collection, Everyone on the Moon is Essential Personnel, Jarboe knowingly (and endearingly) channels Kafka. But unlike Kafka’s Gregor Samsa, who awakens from bad dreams to find himself transformed into a “monstrous vermin,” the ebullient narrator of “I Am a Beautiful Bug!” longs for this transformation, using up all their earned time off (and presumably money) to cross an international border and undergo full-body reconstructive work by a famous plastic surgeon. When asked which features they would like to accentuate, the narrator of “Bug!” replies, “Oh, a little bit of everything […] I’d like about six legs and the antenna to be as long as you can make them […] Some fun stripes or dots on my shell, too, if you can?” Jarboe first acknowledges The Metamorphosis in this scene, with jocular references to getting “the works […] just like Gregor Samsa!”

But as “Bug!” progresses, with one bureaucratic, existential nightmare heaping upon the next — all of which, it should be noted, the narrator meets with astounding glee — Jarboe once again invokes Kafka, this time through the voice of the director of the Registry of Motor Vehicles: “You do realize the bug in the Kafka story was a metaphor, right? […] It’s meant to be ambiguous, symbolizing alienation and self-denial.” Here, the narrator, who has flown to the ceiling of the waiting room, to “shriek without bothering anyone else” about the labyrinthine task of obtaining an updated driver’s license, so that they can unfreeze their bank accounts and buy beer, makes the statement, “I am not a metaphor.” The declaration is heartfelt, but the director, who is closing in with a broom ready to shoo the unwanted guest, scoffs, “I wrote a paper on Kafka in college […] I think I know what I’m talking about.”

Metaphors might be out the window, but the hilarious and the absurd present magnificently in “I Am a Beautiful Bug!,” as they do in many of the other stories in Everyone on the Moon is Essential Personnel. In general, this confluence of elements in Jarboe’s stories relates to bodies. The altered (and dynamic) body serves many purposes here, the first and foremost being to point to the fact that the body is an act of creation, a work in progress. “The Android that Designed Itself,” a flash piece that complicates ideas of divinity, opens with a guiding question: “Why does God create grapes and wheat, but not wine and bread?” The answer: “God does this because God wants us to share in the act of creation.” Note the present tense. This isn’t a staid theological argument about a deity who once made the world — this is an ongoing attempt to make sense of having a body in the contemporary here and now.

Why are some bodies considered strange and others beautiful? Why are some bodies acceptable and others disdained? The simplest answer to these big questions is culture — culture dictates, to a large extent, who and what we see as normal. Within that context there are further sub-groups of influence, chief among them the family unit. Jarboe has a keen eye for the paradoxes of both. Consider “The Heavy Things,” a brilliant, if painful, piece of flash that centers around a narrator whose menstrual flow is accompanied by “needles, and small keys, and decorative screws, and the tiniest little pair of scissors, like something you’d get for a doll.” As time passes, these objects grow larger — “a nail clipper, a construction screw, and a hex key” — and the narrator seeks help from a doctor to stem the tide. The doctor reluctantly offers hormone therapy, and the narrator enters a brief state of reprieve, until “things changed in the world and medicine got expensive and hard to find and the sliding-scale clinics closed.” There’s the possibility of obtaining the needed hormones under the table, but they won’t come fast enough. The narrator begs her parents for money, but the parents balk. Mom suggests a detox. Dad avoids eye contact. Eventually, desperate, the narrator fesses up to the unwanted objects. Dad finally speaks, letting the narrator know “it was your grandmother who had all the gadgets in the house when I was growing up. She found it very empowering.” To close the story, the mother chimes in, registering her request for a knife set for Christmas. Jarboe’s wicked sense of humor is on display throughout the story, but beneath it lurks a larger statement about the institutions — cultural, medical, familial — that limit our movement in the world, not out of malice, but out of obedience to misguided cultural ideas of normalcy, and sometimes, bafflingly, out of love.

Familial constraint comes up again in the fairy-tale-esque “Estranged Children of Storybook Houses,” a sad yet redemptive tale that follows a neurodivergent narrator, whose family blame “the folk” for their daughter’s “inappropriate” behaviors. The parents alternately love and revile their child, but the narrator’s brother is especially cruel, even once, in childhood, trying to “burn the fairy” out of her with the hot end of a fireplace poker. Eventually, the narrator leaves home in search of the child whose place she has taken. She finds her double, the supposed “child of reason,” and in attempting to explaining the situation, provokes the double to announce, “‘My parents, hm? Mother, father, brother, sister, family. […] Seems like some kind of weird blood cult.’” And, given the circumstances, it really does.

Jarboe (who uses the pronouns they/them) has a knack for what they call in “The Nothing Spots Where Nobody Wants to Stay” (a contemporary, post-9/11 blend of fabulist realism) “liminal spaces,” portals that “seem to possess a will of their own and something like a sense of humor.” In fact, that line might be well put to describe this collection as a whole. The stories can be categorized as speculative for sure, but, in truth, they resist simple categorization, defying genre to create something gorgeously fresh and illuminating.

“Estranged Children of Storybook Houses” sits beside “The Seed and The Stone,” “We Did Not Know We Were Giants,” and “As Tender Feet of Cretan Girls Danced Once Around an Altar of Love” in mythic, fairy-tale territory. Then there are “The Marks of Aegis,” “I Am A Beautiful Bug!,” “The Android that Designed Itself,” and “The Heavy Things,” which can be classified as body horror, but with a subtle subversion of that genre: rather than fear or panic arising from their alterations, the narrators are proud, gleeful, or at the very least curious, hopeful. If body horror as a genre typically uses graphic disturbances of the body to induce fear in its audience, then Jarboe’s visceral imagery accomplishes something different. Instead of terror, these body horror stories evoke empathy and understanding. A few other stories, including “Self Care,” “My Noise Will Keep the Record,” and the title novella, are mid-apocalyptic — their worlds are daringly close to economic and climate collapse, but humanity continues to hang on, half believing in new possibilities, which usually means the rich selling “piecework by the half pennies” to the less fortunate. Jarboe has a knack for capturing the disparities of modern life and pushing them into new worlds — and yet, the results aren’t bleak, not exactly, because the urge toward survival is, amazingly, in Jarboe’s hands, so surreally funny. We may be on our way to the moon in a handbasket, but in Jarboe’s worlds, at least we’ll be laughing (or spouting positive affirmations) on our way.

Despite (or perhaps because of) its variety of lengths and styles, Everyone on the Moon is Essential Personnel succeeds as a cohesive whole. The stories return again and again to the human body, revealing facets from beyond the gender binary, from within the depth of neurodivergence, from the perspective that self-inflicted scars are a thing of beauty. Jarboe’s narrators carry these stories with a disarmingly candid and mercilessly observant wit. Take Anthony, the “gay transsexual witch” at the helm of “Self Care,” who wastes no time pointing out the differences in how the haves and have-nots deal with rising seas:

Fuckos in this stupid town think nobody notices how when the tide just keeps coming in without going out again that “some” neighborhoods get sunk forever as an “unfortunate side effect of coastal flooding” while others become the sexy hip cool new “seafloor village.”

There isn’t much that escapes Anthony’s eye over the course of the story — he’s a modern prophet and blabbermouth — and his incessant, prickly astuteness drives pretty much everyone away, even those who claim to want to help him, but he does have the last laugh.

What is so striking about the stories in Everyone on the Moon is Essential Personnel in general, and “I Am a Beautiful Bug!” in particular, is their gleeful reenvisioning of the travails of being human. If Gregor Samsa grows feebler and more starved by the day, crushed by his family’s treatment of him, then the exuberant narrator of “Bug!” flies a different path. In the final scene, when the landlord finally calls in an exterminator, the narrator chooses to grab some marmalade and escape “just as the clouds of poison billowed.” They tell us, “I chose in that moment to have a joyful attitude. I chose to be ecstatic, even! I was a huge, beautiful bug! Hooray!” The flight appears like a deranged Instagram post — the marmalade, the cloud of poison, the declaration of joy — and while we might certainly read into it a sense of irony, that seems beyond the point. The story closes with the bug narrator hijacking the exterminator’s van and heading west, gathering more beautiful bugs as they make their way across North America, wreaking havoc on the dominant landscape and paradigm, rolling up “all the land we passed through into a dung ball like no one had ever seen before, turning all of it over and over into something a bit more positive.”

Jarboe’s vivid imagery underscores a distinctive view on dynamism and mutuality: the world and the body are endlessly intertwined and reflective in Everyone on the Moon is Essential Personnel, and the results are dizzying and painful and, ultimately, glorious.

¤

LARB Contributor

Sara Rauch is the author of What Shines from It: Stories. She has covered books for Lambda Literary Review, Bustle, Bitch Media, Colorado, Tupelo Quarterly, and more. She lives with her family in Massachusetts. Her website is www.sararauch.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Door for You Alone: Reading Kafka’s “The Trial” in Self-Isolation

Robert Zaretsky reads Franz Kafka’s “The Trial” under quarantine.

Banking on the Future: Ian McDonald’s “Luna: Moon Rising”

Hugh Charles O’Connell observes "Luna: Moon Rising" by Ian McDonald.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!