The Black Girl Looks at Other Black Girls: On “This Will Be My Undoing” by Morgan Jerkins

The themes in "This Will Be My Undoing" are the safe, plodding kind expected from so-called diverse writers.

By Khanya Khondlo MtshaliJuly 24, 2018

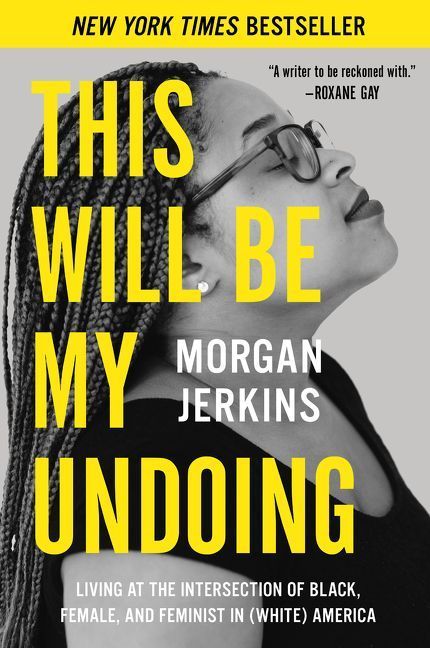

This Will Be My Undoing by Morgan Jerkins. Harper Perennial. 272 pages.

IN This Will Be My Undoing: Living at the Intersection of Black, Female, and Feminist in (White) America (Harper Perennial), writer Morgan Jerkins wrestles with what it means to navigate an America that remains hostile to the existence of black women. Though she wields the plural with ease throughout this collection of essays, Jerkins emphasizes that her experiences aren’t to be taken as a “one-size-fits-all tale” on black womanhood. Instead, she hopes they will become part of many black female narratives, which are “worthy of being magnified for all their ugliness, beauty, mundaneness, and grandeur.”

The themes in This Will Be My Undoing are the safe, harmless kind expected from so-called diverse writers whose biggest drawing card, according to the industry, is our “identity” and “lived experience.” Over 10 essays, Jerkins writes about buzzworthy topics and milestones in her life, such as her first brushes with racism, the politics of black women’s hair, traveling abroad while black, and the importance of former First Lady Michelle Obama. She describes her undergraduate years at Princeton with a wistful fondness, journaling the experiences that shaped her sensibility as a writer and prepared her for the challenges of young adulthood in New York City. While Jerkins writes clearly and precisely, her prose can veer toward the pedestrian. She relies on familiar metaphors and thinkpiece-friendly aphorisms to convey her observations. Often, This Will Be My Undoing feels like a memoir for an older, more naïve internet age. It harks back to the days of the “first-person industrial complex,” where publications would bait young women to cobble together their best traumas, only for them to be paid in exposure and virality. It’s also reminiscent of the time, which some may argue we still live in, when young black writers were encouraged to turn normal, everyday life events into after-school specials for white liberals desperate to be scolded for their racism, and do nothing about it.

Before the terms “intersectionality” and “unapologetic” had been exhausted within the culture, and before “woke” was turned into a slur by aging contrarians reprimanding college students in op-ed columns, there was a real sense that Ferguson had pushed publications to reckon with the uprisings happening across the country, and address, however dubiously, the stifling whiteness of their newsrooms. In an essay for Lenny Letter, Jerkins writes that she got her start as a writer after the death of Mike Brown in August 2014, which compelled her to capitalize on the racial tensions and strife to secure “more bylines, money, contacts, [and] influence.” For those who weren’t paying much attention to mainstream media’s shift from mocking hashtag activism to becoming reliant on the terminology dispersed by the people covering the #BlackLivesMatter movement, Jerkins may appear to be onto something fresh, perhaps even insightful. But for those who spent years using social media to expand upon ideas founded in black feminist, Marxist, and queer scholarship, what Jerkins covers in This Will Be My Undoing is overly familiar, if not overdone.

In the first essay, “Monkeys Like You,” Jerkins describes the cheerleading tryouts she attended as a 10-year-old developing an awareness of race. She writes about wanting to be a white cheerleader with straight hair and a svelte body. She subjects her body to punishing routines and forces herself to smile at older white judges, who seem amused by her enthusiasm. Along with three other black girls, who seem to exist solely as plot devices, she fails to make the team. Jerkins accentuates the importance of this moment. Not only was she forced to confront early disappointment as a small girl, but she was also introduced to the giddy reception awaiting young white women who simply have to show up and try. But however earth-shattering that event may have been for Jerkins, it doesn’t translate onto the page. Her recollection of this disappointment fails to earn the pageantry and melodrama with which it’s conveyed. The name of the essay derives from a comment made by a Filipina “friend” of Jerkins who tells her that she didn’t make the squad because they “didn’t accept monkeys like [her].” Yet this moment, which is central to the entire piece, gets buried under Jerkins’s efforts to present the tryouts as something other than a generic tale of a child’s first encounter with failure.

In the latter half of the essay, which a sharper editor would’ve turned into a separate piece altogether, Jerkins writes about the difficult relationship she had with other black women in high school when her family relocated from Egg Harbor Township to Williamstown in New Jersey. As she enrolls in a new school, she finds herself targeted by Tiana and Jamirah, two black girls who’ve decided to make Jerkins the subject of their relentless bullying. At times, Jerkins’s reflections of black womanhood wade into a kind of tragedy and despair. She asserts that this period of her life points toward the “violence [black women] hurl at one another,” making little attempt to complicate the sweeping conclusion she posits as scripture. Jerkins focuses mostly on Jamirah. As is typical with many black women whose performance doesn’t conform to bourgeois femininity, Jamirah is depicted as brash, cocky, and loud while Jerkins portrays herself as quiet and bookish. She acknowledges how much she was shaped by the respectability politics of her mother through her preppy get-up of argyle socks, plaid skirts, and a Dooney & Bourke wristlet. She admits that she saw herself as superior to girls like Jamirah, who gets a starring role in Jerkins’s anti-black girl fantasy, in which Jerkins envisions Jamirah getting arrested by cops while she gets to walk away smug and unscathed.

Whether this fantasy came from a younger Jerkins looking for a sense of control and escapism, it is jarring to see it written so plainly. Jerkins admits to knowing about the menacing and surveilling presence of the police within black communities yet she doesn’t seem willing to interrogate why she’d indulge in such violent, white supremacist ideation. She atones for her behavior retroactively, promising to check herself whenever she assumes her “lighter skin color, or education, or behavior” warrants the kind of arrogance and anti-blackness she displayed toward Jamirah. But this promise seems more like an ass cover than an apology, especially given the culture of public “draggings” online. And when she concludes the essay by praising Jamirah’s “agile cadence” and deciding they both “needed each other,” we’re left with a glib and conceited reading of a relationship that’s presumed to be mutually beneficial because of the insight and content it offers the author.

Jerkins is at her best when she turns her focus inward, and narrates, without consideration of social media consensus, some of her thoughts and experiences with desirability, sex, and relationships. In “A Hunger for Men’s Eyes,” she writes of a relationship she was trying to have with a man named Bradley, a childhood friend and longtime admirer. Though she hadn’t spoken to him since high school, when he invites her to Nevada before her graduation, Jerkins doesn’t hesitate to say no. But this isn’t the most emphatic yes. For women who love and have sex with men, this familiar feeling of ambivalence tinged with the need to be touched, fucked, or loved can be perplexing. Our romantic and sexual needs are often described in defensive or protective terms, creating a world where the stakes are always war-like, the option of “meh” never available, and the distinction between good and bad unambiguously clear and gendered.

As one grows past the need to be reassured about a right to romance and sex, one becomes aware of the absence of language describing the anxiety of wanting affection and pleasure in order to feel less alone or, as a good friend once put it, “fundamentally lovable and human.” When Jerkins writes that her “four-year dry spell at Princeton was steadily turning [her] cold, bitter, and emotionally mute,” one understands this conundrum even though it could do with more lively and vivid wording. There’s something quite Catholic about the combination of sexual repression, panic, desire, pride, and resentment she feels at the end of her undergraduate career, when she’s trying to play catch-up in an environment where many people have already had their formative romantic and sexual experiences. Her attempts to negotiate her way into a relationship with a man she’s convinced herself she loves, only for him to reject her, speaks to the cruel and ridiculous fate that faces women who feel they’re lagging behind, but don’t quite know which race they’re running.

Unfortunately, other parts of “A Hunger for Men’s Eyes” see Jerkins rely on the same generalizations of black women without pausing to investigate the neat verdicts that she reaches. She writes that she’s “never talked to a black woman about the loss of her virginity and heard her describe it as anything other than traumatic.” It is not the place of the reader to question the veracity of this statement, but it is fair to wish Jerkins had taken a different approach. She could have specified why, if given permission, these first-time experiences were so awful. She could have used reportage to unpack a phenomenon affecting certain black women losing their virginities. Jerkins also appears to ignore that the “adequate foreplay and pleasure” black women supposedly experience in the bedroom isn’t simply product of being inhibited and ashamed about the sex, but rather an example of how our cissexist and heterosexist world treats the male orgasm as the most tantalizing part of the sexual act. This is what is most frustrating with This Will Be My Undoing: Jerkins is so determined to present black womanhood as a state of pointed suffering that she ignores the myriad of reasons behind the statements she proposes as facts.

In the final essay, “A Black Girl Like Me,” Jerkins tries to look at the dynamics among black women in media circles. She brings up two different exchanges, though the word seems generous here, with two black women writers whom she respected from afar. During this time, Jerkins describes being rejected from multiple jobs even though she graduated from an Ivy League school and secured steady work as a freelancer. She speaks of the insecurity of not having the “212 or 718 area code” of the writers whose approval she yearned for. She writes of having to summon the courage to reach out to both black women writers, one of whom “regularly wrote for the Guardian,” and the other part of the “circles that [Jerkins] could only bounce around but never infiltrate.” She asks the one to recommend her as someone to commission from at the Guardian, and the other for a contact at The New Yorker.

While they don’t refuse her requests, they offer responses that dissatisfy Jerkins. She’s contacted by an editor at the Guardian, but the black woman writer admits “she hadn’t spoken to the editor before [they] reached out.” The black woman writer with The New Yorker contact advises Jerkins to wait for an editor at the publication to get in touch with her. Jerkins barely considers why these harmless responses dismayed her, but determines that they are “act[s] of withholding” that form “part of the crabs-in-a-barrel theory that stymies black people in general and, in this case, black women specifically.” It is a strange conclusion to reach given how thin and brief these interactions are. Many writers are lucky if an editor decides to offer them advice let alone respond to an email, a fact Jerkins appears blithely unaware of. Her assertion that black women can’t advance each other because of some inherent need to be the one and only, a folksy adage that has long reached its expiry date both in the diaspora and on the continent, seems like a convenient way to avoid discussing her potentially intense relationship with ambition, competition, and envy as it relates to other black women. And despite how much these exchanges have rattled Jerkins, they are not the stuff interesting and thoughtful essays are made of.

That said, some writers might find Jerkins’s honesty about wanting to be part of the “Who’s Who of New York media” quite relatable. Having to watch people you admire share each other’s articles, and contribute funny memes and gifs on each other’s threads makes you wish to be included in the fold, only to curse yourself for falling victim to such teen-flick clichés. It can feel like you’re being rejected from folks with whom you’ve presumed kinship based on following the same people, live-tweeting the same shows, and loving the same Beyoncé. But this is where Jerkins misses an opportunity to examine how social media can see people build community with those who share similar views as them without knowing them, or befriending them. What she could’ve accounted for is the random and unexpected ways working relationships and friendships are built in a city that is unkind to those whose dreams and secrets it knows intimately. Nowhere does she factor the ambivalence and fatigue of black women writers attempting to make a space for themselves, never mind their peers, in an industry where their talents are underestimated or ignored. And though Jerkins says she doesn’t “agree that every black woman has to be friends with every other black woman whom she meets,” we’re left to wonder what she wants from other black women writers and why she feels so entitled to their time and acceptance.

Marginalized writers are often asked to shed light on our identities. These narratives are frequently presented as timely dispatches from individuals who position themselves as the most eloquent speakers on the state of affairs among people with those identities. Among liberal audiences, they are received with exuberant fanfare. They’re declared “important” and “necessary” by critics who don’t seem to know how to engage with work from marginalized writers beyond stressing that it should exist. As the writer Lauren Oyler notes in an essay for The New York Times Magazine, oversizing the “necessity” of a text or work of art creates a value system that prizes moral urgency over aesthetic achievement. Morgan Jerkins is an industrious writer whose success is undoubtedly a product of her work ethic and determination. But This Will Be My Undoing falls into the tradition of art that upholds an easy and showy moralism. In an age where we want to be reminded of our good values through the art we consume, it is truly a book of its time.

¤

LARB Contributor

Khanya Khondlo Mtshali is a freelance writer and critic. Her work has appeared in Bookforum, The Rumpus, the Guardian, The Mail & Guardian, Popula, The Outline, and Quartz.

LARB Staff Recommendations

New Black Gothic

Sheri-Marie Harrison on "This Is America," "Get Out," "Sing, Unburied, Sing," and the new black Gothic.

Twenty-First-Century Word Paintings: Nafissa Thompson-Spires’s “Heads of the Colored People”

Thompson-Spires’s satire, oriented around questions of blackness, joins a particular tradition of African-American sardonic absurdism.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!