The Banality of Otherness: On Stephenie Meyer’s “Midnight Sun”

The latest installment in the “Twilight” series retells the story from Edward’s perspective.

By Nicole BlackwoodOctober 31, 2020

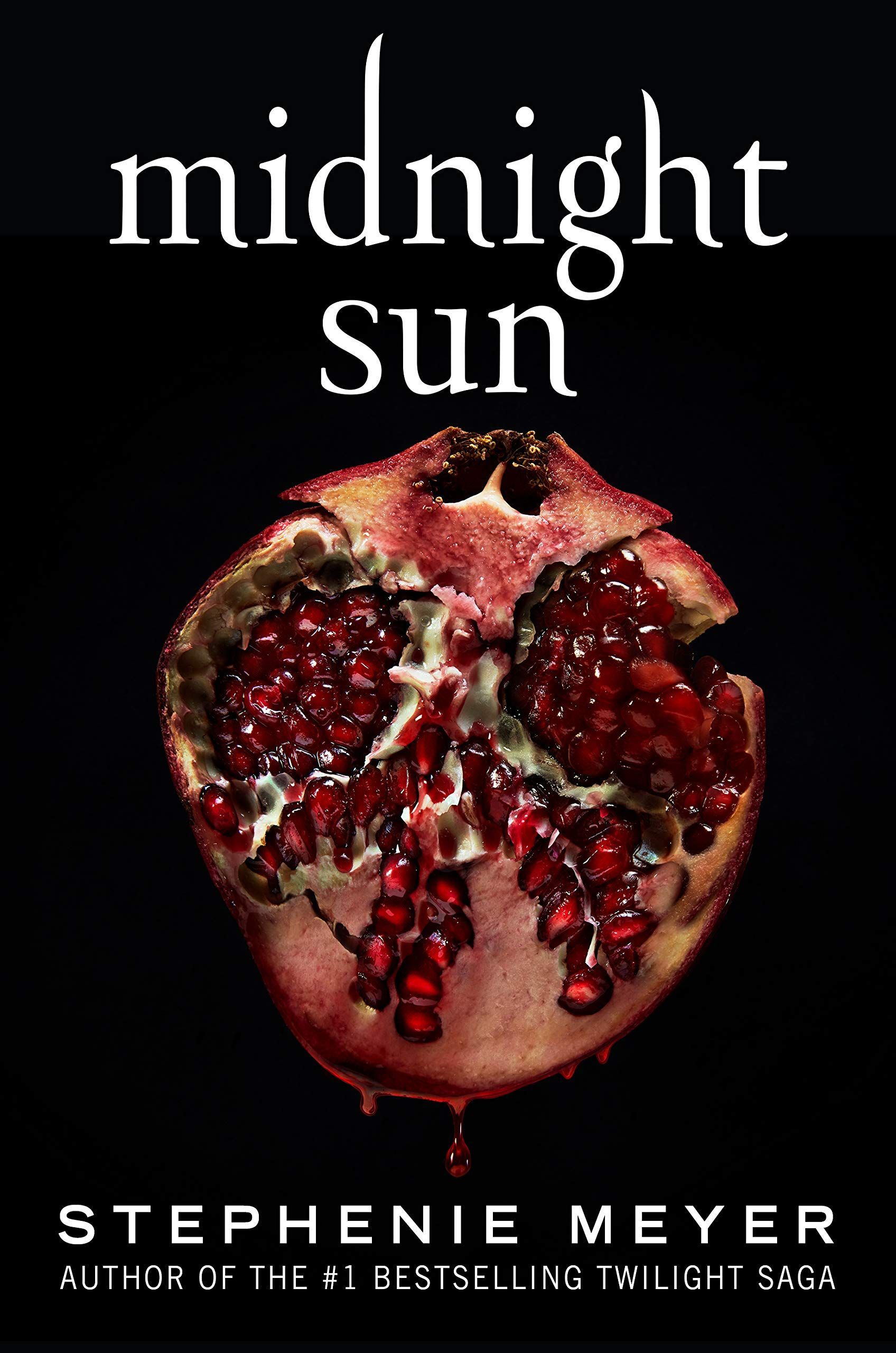

Midnight Sun by Stephenie Meyer. Little, Brown Books for Young Readers. 672 pages.

THOUGH MOST WILL CREDIT — or curse — Twilight for ushering in the vampire craze of the early 2010s, it’s always been a highly referential text. If, back then, you didn’t pick up on Bella name-dropping Jane Austen every few pages, Stephenie Meyer was crawling out of her money pile daily to remind you that, yes, Bella Swan and Edward Cullen were the Elizabeth and Darcy of the digital age. They hate each other, and then they don’t, with a twist — he has fangs, guys! But the parallel fails to stretch any further because while Pride and Prejudice remains high stakes even on a reread, Twilight feels dully inevitable. Bella moves to Forks, Washington, meets Edward, and falls head-over-Converse — there’s never a real alternative, even after the series’s love triangle emerges in the sequel.

Midnight Sun, Meyer’s latest venture (in the works for over 12 years), is an attempted complication. After meeting khaki-clad vampires and werewolves through Bella’s first-person narration, we’re finally granted access to Edward’s head, put through the paces of first love alongside a 100-year-old vampire. Meyer has said that her interest in Edward’s point of view lies in his inhumanity, his otherness. Her tendency to otherize is a longstanding one — Jacob Black, Edward’s rival for Bella’s affections, is a member of the Quileute tribe and a werewolf, and Meyer’s decision to exploit (and animalize) Indigenous identity has been rightly criticized.

In Midnight Sun, the author’s fixation on “the other” is almost pathological. Because the book follows a twice predetermined path, Edward’s narration is less exposition than it is a damning self-indictment — he refers to himself as “alien,” “evil,” a “monster,” a “devil,” a sinner who can receive “mercy” only from Bella’s acceptance. On one level, this feels obvious, and on another, like overkill: the Cullens are “vegetarians” who attempt to live a mostly human life, Edward only ever killed sexual predators and murderers, and he has no religious dogma to explain his obsession with punishment. We’re given the cycle, but never shown where or why it starts. Luckily, plot in the Twilight-verse comes second to meandering dialogue (and baseball!), so there’s plenty of time for the reader to trace a potential origin.

It’s not a leap to read Edward’s otherness as sublimated queerness, nor am I the first to do so; many have noted the assimilationist nature of the Cullens’ repressive lifestyle, their makeshift nuclear family, and, by extension, Meyer’s critical distance from the deviant vampire. Surely no one would root for a sinner who took pleasure in his desire to sin — Edward is “other,” but this otherness rarely manifests itself supernaturally. He can read minds, he can hunt prey, but somehow, most importantly, his inhumanity is a draw for humans, making him Forks High’s most eligible bachelor. And this same, sexual availability sets him apart from even his family; while his siblings are all coupled off, Edward tells us that he “was the only one alone,” othered among others. His mother worries about him — in 100 years, he’s never found a girl to love.

Enter Bella. As Edward grows infatuated, he leans on reference as a crutch; his primary struggle is learning to enact heterosexual love, something he’s read about in books like Austen’s but never experienced. “Some long-buried instinct had me reaching out toward her,” he narrates in one of their early interactions, “[and] in that one second I felt more human than I ever had.” This fumble is an oddly queer emergence from repression, all barely named desire and surfacing need (Bella, too, has never been interested in anyone but Edward).

If nothing else, Midnight Sun emphasizes the roteness of their courtship, even as Edward denies and deflects his budding feelings. His instincts always lead to banal conventionality: he takes Bella to dinner, asks to be called her boyfriend, and later tricks her into attending the prom. Though he often worries about “losing control” around Bella and, you know, eating her — her blood uniquely appeals to him — this fear never feels fully realized. For all her interest in otherness, Meyer writes a vampire with near-perfect control over his deviance; his shiny surface is all we see, and it’s all we get.

But because Edward can read minds, he often views himself from the perspective of outsiders, constructing a palatable identity for their benefit. No dinner date or dance can make these moments less fraught, or less innately queer; beyond the Cullens’ desire to be “close enough to human to pass,” Edward is uniquely obsessed with tamping down his “alien” appearance. His first encounter with Charlie Swan, Bella’s police chief father, reveals what human interaction has so far been for him — Charlie’s instinct is fight-or-flight before he fully registers Edward’s apparent humanity. “His brain would force him to ignore all the little discrepancies that marked me as other,” Edward thinks clinically, noting that this has happened before.

The connotations of “passing” are obvious and, in this instance, especially bleak. In the Twilight films, more is made of Charlie’s law enforcement career, with him unknowingly hunting vampires under the assumption that he’s policing animal attacks. Still, in Midnight Sun, this meeting scene goes some way toward explaining Edward’s singular fixation — Chief Swan is, in Meyer’s undeniably traditional world, the gateway to a heterosexual future with Bella.

Bearing this in mind, the infamous meadow scene, in which Edward reveals his glittering skin to Bella, signifies rare, genuine freedom. It’s hard to read the scene without thinking of the decade-old jokes and GIFs: yes, he’s a vampire who sparkles in the sunlight, and, yes, that’s pretty dumb. But through Edward's narration, the scene becomes something close to moving. We’re told of the meadow’s existence early on through the visions of Edward’s psychic sister, Alice, and Edward is left to worry about what will happen when he brings Bella there on the world’s weirdest date — whether he’ll kill her by accident or breach some new understanding. Before the date, he decides that he’ll show her the reality of sunlight on vampire skin. Though he worries about the, uh, possible murder, Bella’s hypothetical disgust toward his body is his real fear. “So what if Bella found me repulsive?” he deflects. Then, later: “I couldn’t bear the first reaction on her face.”

You have to hand it to Meyer for making it a compelling image. Edward steps out of the forest, into the light, and Bella accepts him — though, at first, she believes he’s burning alive, a split-second beat that reminds us of Edward’s obsession with judgment, and which liberates him from it. While he previously viewed his vampirism as an inner “monster,” the split personality that Charlie saw in his doorway, he now recognizes that “there was no separate monster and never had been one. […] I had — as was my habit — personified that hated part of myself to distance it from the parts that I considered me.” Though his narration remains frustratingly anxious (Meyer sure has her writing tics), Edward rarely reaches the same level of self-damnation. Visions of hellfire recur after Bella is put in physical danger — he even plots to leave her, believing she’d be safer without him. Still, this repression feels superficial, a reluctant function of the fixed plot. If there’s no monster, there’s nothing left to subdue.

It’s reductive to call the meadow scene a coming out — I’m not suggesting that vampirism and queerness directly correlate in Midnight Sun, especially because, in most ways, Bella and Edward enact perfect heterosexuality. Yet, every so often, that heterosexuality is strangely queered: too referential, allowing glimmers of otherness to creep beneath the surface of what should be Elizabeth and Darcy’s reincarnations. Edward represses not only his self-determined sin, but also his capacity to love — both emerge simultaneously in the meadow. Even Darcy never gets such a moment in the light.

In one of the book’s odder, and more genuinely romantic, moments, Edward swallows Bella’s tears; the Cullens believe that only blood moves through their bodies, so Edward thinks that he may “always have this piece of [Bella] inside [him],” even after she inevitably leaves. Bella can’t understand the gesture, and Edward tells us he “had no sane way to explain.” The story quickly veers back into exposition, but we know the tear remains lodged in Edward’s throat. We recognize it for what it is: evidence of love, building a home in the body he always hated.

¤

LARB Contributor

Nicole Blackwood is a Boston-based journalist interested in writing about art and identity. She previously reported for the Chicago Tribune’s Features desk.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Stake Not the Undead: Vampires in the 2020s

Karina Wilson traces the lineage and history of the vampire story and considers why it is more relevant (and marketable) than ever before.

Vampire Socials

The distressingly human lives of vampires today

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!