The Ashtray Has Landed: The Case of Morris v. Kuhn

Much of "The Ashtray" is witty, ebullient, and generous. Errol Morris shares his wide range of interests, and his enthusiasm for philosophy is infectious.

By Philip KitcherMay 18, 2018

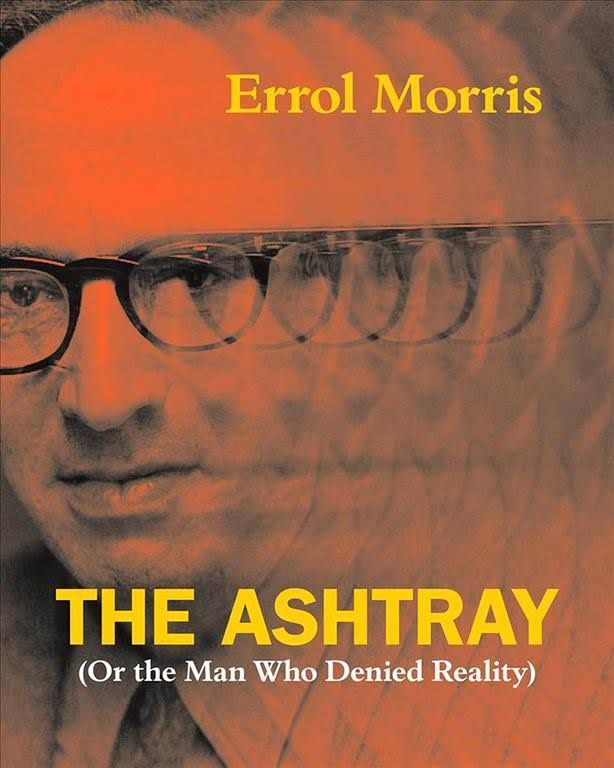

The Ashtray by Errol Morris. University of Chicago Press. 192 pages.

DURING THE PAST DECADES, Errol Morris has established himself as a distinguished filmmaker whose documentaries, notably The Thin Blue Line, have won prestigious awards and wide acclaim. For Morris, it was not always thus.

Almost half a century ago, as a recent graduate from the University of Wisconsin fascinated by the history of science, the young Morris was rejected by some of the most prestigious graduate departments. Thanks to the efforts of one of the field’s major stars, Thomas Kuhn, he did eventually find his way to Princeton’s program in the history and philosophy of science. But his time there did not go smoothly. Matters came to a head in a one-on-one discussion of a paper he had written for Kuhn’s seminar. The emotional temperature rose. And then rose some more, until the tête-à-tête was ultimately punctuated by an overflowing ashtray. Launched from Kuhn’s hand, the ashtray hurtled across the room.

Nobody will ever know if the projectile was thrown at Morris or whether it was simply thrown. In any event, no physical harm was done. What is known is that the incident was followed, quite quickly, by Morris’s forced exit from Princeton. Initially undaunted, he pursued further graduate study (at Berkeley) before deciding that academic life was not for him. His new book, The Ashtray, revisits this now transcended past and records his intellectual enthusiasms. At its center is the memorable episode of the flying ashtray — hence the title. Central to the book as well is the work and character of the man who threw it and allegedly “denied reality.” As Morris disarmingly confesses, this book is a vendetta.

A one-sided vendetta, of course.

So far as I know, Kuhn never recorded his views about what happened that afternoon in a room in Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study. There would have been no reason for him to do so. Why write about the pugnacious behavior of a first-year graduate student? Even so, the young man had clearly gotten under his skin: Kuhn had typed 30 pages of comments on what he viewed as Morris’s misguided essay. Does the length signal obsessive hostility, as Morris interprets it; or was it an admirably conscientious effort at helping a talented but errant tyro? Kuhn has been dead for more than two decades. History is written by the survivors.

It is also an odd vendetta. Much of The Ashtray is witty, ebullient, and generous in spirit. Morris shares his wide range of interests, and his enthusiasm for philosophy is infectious. Brilliantly chosen images adorn the pages. To be sure, professional philosophers might pay more attention to crossing t’s and dotting i’s, but none would rival Morris’s élan. He conveys the excitement of what might seem abstract intellectual questions. Vendettas are typically grim. This one is more of a romp.

¤

Yet the stiletto has to be thrust home. Repeatedly it stabs. Until no doubt remains about the death of the victim. T. S. Kuhn, author of the immensely influential book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, a book assigned to countless students of the philosophy, history, and sociology of science, is exposed as a corrupter of the youth, the father of relativist and postmodernist heresies, an unoriginal borrower from more insightful thinkers, an arrogant dogmatist, implacably intolerant, ill-tempered, confused, contradictory, vapid, and obsessive. In Morris’s telling, the man who denied reality could not face up to what he had done. When the world — in the person of a first-year graduate student — called his bluff, the charlatan’s only recourse was to throw a heavy object.

The story Morris tells reminds me of a famously grand gesture by a great 18th-century celebrity. The diarist and biographer James Boswell describes his friend Dr. Samuel Johnson’s “refutation” of the idealist philosopher Bishop George Berkeley. Standing up for realism and so occupying the role Morris assigns himself in this book, the great doctor dramatically kicks a stone. No contemporary reader of Berkeley, even a beginning undergraduate, would take Johnson’s “argument” seriously. Berkeley’s idealism was itself a riposte to Locke’s invocation of a world of substances beyond the “ideas” perceiving beings come to have. Taking himself to be the advocate of common sense, Berkeley viewed all things as complex collections of perceptual states. When Johnson’s gouty toe met with stone, he acquired a sequence of undoubtedly painful “ideas.” Some of those ideas belong to the object we think of as the stone.

Morris attacks Kuhn in the time-honored Johnsonian style. The Ashtray goes astray already at its subtitle. Just as Johnson made no attempt to interpret Berkeley’s position, Morris has no interest in considering what Kuhn might have had in mind. Kuhn was neither a relativist nor an irrealist. His repeated efforts to distance himself from both views — his repudiations of swarms of would-be disciples claiming him as their guru — strike Morris as evidence of confusion or dissimulation. Invoking the ideas of some of the most eminent American philosophers of the recent past, Hilary Putnam and Saul Kripke in particular, he writes as if Kuhn’s position is quite simply absurd. How silly to deny reality!

The lively expositions of Putnam and Kripke are part of what make The Ashtray worth reading. What role do they play in the vendetta? Certainly not one of exposing the errors of Kuhn’s ways. Rather, Kripke and Putnam provide tools for developing a resolutely realist account of scientific practice and its history. In short, they provide defensive weapons. Morris does not actually try to articulate Kuhn’s ideas, even if only just to show us how they collapse. Rather, at his most charitable, Morris presents a caricature of Kuhn, juxtaposing it with a partial sketch of a rival realist approach, one with debts to Kripke and Putnam.

But my judgment is slightly unfair. Morris is not the originator of the cartoon. It has been around for decades, readily available to anyone who wanted to carry out a vendetta.

¤

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions was published in 1962, as the last volume in the International Encyclopedia of Unified Science. The editors (known for their devotion to logic and rigorous argument) had commissioned a monograph on the historical development of the sciences from a young ex-physicist-turned-historian. Surviving documents suggest that they were happy with what they received.

Many of the scientists who read Kuhn’s book were also positive about it. They typically found the description of “normal science” (occupying the first half of the book) far more insightful about scientific practice than the usual formalized reconstructions of theories, beloved of other philosophical treatments. Equally welcome: Kuhn’s emphases on tacit knowledge, and on how puzzles test the ingenuity of scientists and their unwillingness to abandon existing approaches in the absence of a promising successor. And, of course, the idea of something lurking behind normal science, not to be identified with an articulated theory or a set of rules for research, but from which articulated theory and rules might flow — a paradigm — caught their imagination and that of the broader public. Kuhn admitted the ambiguities inherent in his usage. He even attempted to recall the term. But it was too late. “Paradigms” had legs of their own; they are, apparently, here to stay.

So, initial success, at least in some quarters, and for some aspects of Kuhn’s book. Within a decade, however, a tempest erupted. Focusing on the second half of the monograph and its treatment of revolutions, and particularly on a few colorful formulations (Kuhn’s “purple passages,” as they have been called), philosophers were outraged. The growth of science was portrayed in terms of “conversion” and “faith,” they complained, rather than as an exercise in reason and evidence. Truth had been discarded. Revolutions were now seen as actually “changing the world.” In the manner of Cato on Carthage, Kuhn’s deviations were fervently denounced. Kuhnian relativism had to be destroyed.

Thus the caricature was born. It still persists in some circles, particularly among philosophers who spend little time on the history and philosophy of science. It lay in Errol Morris’s way, and he found it. During the 1970s and thereafter, the caricature inspired more radical thinkers to embrace relativistic heresies. Kuhn found himself at odds with both sides, arguing with his philosophical critics and with his would-be relativistic allies. As he did so, the contours of the space he hoped to occupy gradually became clearer. Many writers who had taken over various pieces of the caricature (and here I must confess my own guilt) came to recognize what lay behind Kuhn’s more-or-less patient explanations: a Mercutian expostulation — “A plague on both your houses!”

What sorts of lines or shapes, then, did the cartoonists draw, and how exactly did they distort what Kuhn intended?

According to the cartoon — and according to Morris: Kuhn denied the possibility of communication across the revolutionary divide. No — he said that such communication was inevitably partial. The languages of different paradigms are not straightforwardly inter-translatable. Often, no single term in one language will do for a scientifically important term in the other. What one paradigm sees as a “natural” division of the subject matter appears as odd and disjointed to its rival.

Again: Kuhn saw transitions from one paradigm to another as irrational, as acts of conversion. Indeed, Kuhn tells his readers that the decision to embrace a new paradigm (purple passage) “can only be based on faith.” But, on the same page no less, he also characterizes scientists as “reasonable men,” each persuaded by some argument or piece of evidence, although no single argument will serve for all. Reconciling these thoughts requires understanding the kind of “faith” involved. Early on, a new paradigm cannot deliver all the predictions, explanations, and solutions of puzzles offered by the traditional approach it is trying to replace. Even when its successes are striking, they are few — and scientists reasonably wonder whether they can be extended to embrace the full range of what has previously been achieved. Those who “convert” early do so on the basis of “faith” that the old successes will be replicated. Different scientists will take different problems, as yet unsolved, to be crucial. As their favorite critical examples are tackled, they (reasonably!) switch their allegiance.

The final, central charge: Kuhn denied reality. Morris draws his conclusion from a popular cartoonist line: “Kuhn saw revolutions as changing the world. So he can’t think there’s a fixed world, existing independently of human beings and of human knowledge.” Even for many sophisticated scholars, the 10th chapter of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, in which the idea of world changes appears, is “the X-rated chapter X.” Here, then, a longer explanation is needed.

¤

The idea behind Morris’s subtitle, “the man who denied reality,” founders on an elementary observation. Normal science, as Kuhn describes it, makes no sense unless something independent of human investigators pushes back against scientists’ efforts. Without a source of resistance, puzzle-solving would never fail. Let’s call this independent source of frustration “reality.” Kuhn presupposes reality. How then can he deny it?

Morris has an answer to the question. Kuhn was confused, unable to see that his position was self-contradictory — or, more likely, he spoke with forked tongue, expressing himself differently when talking to philosophers than when talking to others (historians, sociologists, et cetera). Yet where exactly does the contradiction come? Is it possible to suppose that, after a revolution, scientists live in a different world while also supposing that reality pushes back against their efforts (their previous and their subsequent efforts)?

For the last 20 years of his life, Kuhn attempted to write a successor to The Structure of Scientific Revolutions in which he would elaborate more clearly the views the earlier monograph had struggled to express. His efforts failed to satisfy him, and the version left at his death (shortly to be published) should not be regarded as the definitive presentation of his ideas. Yet, on the basis of the writings he was content to see in print, it’s possible to see how he tried to square the thought of an independent reality with the thesis of a changing world.

Passages in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions provide an important clue. The first paragraph of Chapter X (whose title is “Revolutions as Changes of World View” [my italics]) ends with a modest proposal: “In so far as their only recourse to that world is through what they see and do, we may want to say that after a revolution scientists are responding to a different world.” Two pages later, at the close of another paragraph, Kuhn invokes William James, declaring that, in the absence of the kind of training that teaches scientists (and, we might add, children) to see, “there can only be, in William James’s phrase, ‘a bloomin’ buzzin’ confusion’.”

The phrase appears in Chapter XIII of James’s The Principles of Psychology, where he describes the experience of the baby, who “assailed by eyes, ears, nose, skin, and entrails at once, feels it all as one great blooming, buzzing confusion.” By contrast, the experience of normal adults, described in a famous earlier chapter (Chapter IX, “The Stream of Thought”), takes their experience of a world as achieved through a process of selection and connection. Using a suggestive (but not altogether straightforward) analogy, James proposes that human beings compose, or construct, the world of their experience, just as a sculptor “works on his block of stone.” He concludes his discussion by recognizing the possibility of different worlds, obtained “from the same monotonous and inexpressive chaos.”

My world is but one in a million alike embedded, alike real to those who may abstract them. How different must be the worlds in the consciousness of ant, cuttlefish, or crab!

Kuhn took up this idea, and further developed it. James contrasts the worlds of different animals to suggest that each species has its own world of experience, dependent on its sensory faculties. Kuhn’s notorious Chapter X seems moved by the thought that there may be myriad human worlds, differentiated by changes in human ways of thinking.

Like James, Kuhn recognizes something independent of observers, something that pushes back against their efforts to interact with it. Both acknowledge reality. But they distinguish reality from the world in which the subject of experience lives. That world contains objects, with determinate boundaries; it contains kinds of things; it contains processes with beginnings and endings. It is a structured world, not a chaos, not a “blooming, buzzing confusion.” We naturally think of our world as containing levers and pendulums, hormones and neurons, financial exchanges and court procedures. In doing so, we reorganize the world our predecessors inhabited. Their structures no longer suit the way we live now. Reality admits many ways of dividing it — although by no means all; it often pushes back. There are no privileged joints at which it must be carved. The worlds of human experience result in part from our biological capacities, and in part from the divisions and connections we construct in attempts to serve our evolving purposes. To quote a phrase from Hilary Putnam, the brilliant subject of one of Morris’s interviews, there isn’t “a ready-made world.” (In their way, those interviews, too, are brilliant, lively contributions to the case against the accused. Yet the words on the page are, inevitably, a selection from what those interviewed said, and it is reasonable to ask if they would always endorse the decontextualized implications of the printed version.)

The realism Kuhn denies is much stronger than any dreamed of in Morris’s excursions into philosophy. It consists of the claim that reality comes pre-packaged, divided up in advance of our cognition of it. The position Kuhn envisages — derived from James, and elaborated in Kuhnian directions by Dewey — may turn out in the end to be incoherent or unsustainable. But it is far more complex and interesting than Morris allows. It poses interesting challenges to the hyper-realism of the ready-made world, and should not be brushed aside by dismissive gestures, citations of authority, or Johnsonian exercises.

¤

Boswell relates another pertinent anecdote about the Great Doctor. Returning from church one day, Johnson encountered a former fellow-student, a Mr. Edwards, whom he had not seen for many years. In the ensuing conversation, Edwards humbly offered an interesting confession: “You are a philosopher, Dr. Johnson. I have tried too in my time to be a philosopher; but I don’t know how, cheerfulness was always breaking in.” One of the delights of The Ashtray is that Morris constantly allows cheerfulness to break in — indeed he dazzles his readers with charming excursions on all manner of topics, from Cervantes and Borges to the Pythagoreans, linguistics, and biological taxonomy. Many of these interludes are as effervescent as they are informative.

Yet we always return to the principal theme, to the attempt to find a final revenge. And the book suffers from that implacable pursuit, as violent in its way as the original throwing of the ashtray. Just as Kuhn’s better self emerged when he was able to escape his sense of being misunderstood and vilified for sins he had never committed, so Morris might aspire to write the delightful book he partially offers here. He is not Prince Hamlet, nor was he meant to be. Better to see himself as a Stoppardian figure, generously lavishing his broad and quirky learning on a comedy of ideas.

The ashtray has landed. It missed. The ideas of the frustrated man who threw it are becoming better understood. The episode is over.

¤

LARB Contributor

Philip Kitcher is John Dewey Professor of Philosophy at Columbia University. He is co-author (with Evelyn Fox Keller) of The Seasons Alter: How to Save our Planet in Six Acts (W. W. Norton) as well as author of Science in a Democratic Society (Prometheus Books).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Dangerous Bullshit

In American politics, we aren’t witnessing an unprecedented outbreak of lying. Another term is more appropriate: bullshit.

What Do We Owe Our Planet?

If humanity were originally charged with the stewardship of this world, as Genesis claims, then it is easy to think we have failed in our duties.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!