The Arab in Winter: On Fabien Toulmé’s “Hakim’s Odyssey”

“Hakim’s Odyssey” is a three-part graphic novel that follows the painful real-life journey of a Syrian refugee fleeing his country’s civil war.

By Andrew MontiveoApril 23, 2022

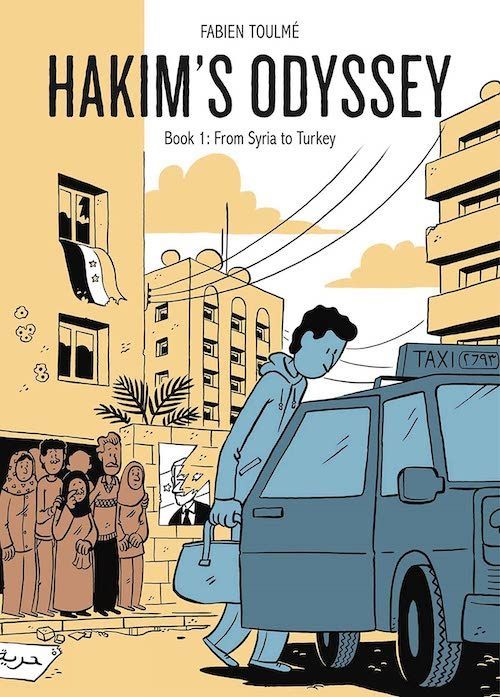

Hakim’s Odyssey: Book 1: From Syria to Turkey by Fabien Toulmé. Graphic Mundi. 272 pages.

ON DECEMBER 17, 2010, a Tunisian vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi doused his body in gasoline and set himself alight. Bouazizi’s act of self-immolation, in protest over the confiscation of his wares, propelled mass demonstrations that ended the long presidency of Zine Ben Ali. Similar protests erupted from Marrakech to Mosul, spurring what has become commonly known as the “Arab Spring.”

More than a decade on, little light and life remain in that spring. The wave of social and political unrest that began in 2010 has yielded sectarian rifts, civil wars, and even counterrevolutions. It has sparked the world’s largest humanitarian crises, deepened regional vendettas, and hardened already rigid autocracies. It would seem the spring was brief and the winter long.

Few have felt that winter as hard as the Syrian people. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights tallied approximately 600,000 lives lost in the country’s ongoing civil war. The United Nations estimates the war has driven a majority of the Syrians — 13.5 million — from their homes. Almost seven million refugees now live outside the country. Many of those Syrians have traversed the Mediterranean, joining the hundreds of thousands of “statistics” trying to rebuild lives, stuck in detention centers, or washed ashore as painful reminders of war and its consequences.

But who are these statistics? What horrors have they fled? What losses have they endured? What hopes do they still have?

¤

These are the questions that haunted Fabien Toulmé, a French illustrator, and drove him to help tell one such refugee’s story. The product of this effort is Hakim’s Odyssey, a three-part series that chronicles the real-life journey of a Syrian refugee fleeing his country’s civil war. Book 1, translated by Hannah Chute and published in the United States last October, documents the title character’s life in Syria and his journeys from the Levant to Anatolia.

In his prologue, Toulmé details his incredulity over fellow Europeans’ passiveness to the plight of refugees. The catalyst for this frustration came amid the fatal collision of Germanwings Flight 9525 on March 24, 2015. The crash, caused by a suicidal pilot, claimed the lives of 150 passengers and crew and received wall-to-wall coverage by the European press.

Yet Toulmé’s book follows that with a much larger tragedy at sea. Four hundred migrants drowned when their makeshift craft overturned in the Mediterranean. European newscasters documented every aspect of the Germanwings collision, hosting biographies on the victims and imbuing them with layers of humanity that audiences would find relatable. “We […] could have found ourselves on the plane,” the author recounts, “but surely not on a makeshift boat, fleeing from a war-torn country, or famine, or both.” Thus the larger loss of life at sea garnered only brief mention, leaving its victims as no more than hollow stats.

As he explains, some 3,500 migrants drowned in the Mediterranean in 2015 alone — equal to 23 Germanwings flights. Among these, there are precious few instances when the fallen do become more than statistics. Toulmé illustrates this with a panel depicting the drowned body of Alan Kurdi, the Syrian toddler who perished at sea with his mother and brother, his body washed ashore in Turkey. The scene of Kurdi lying face down in the sand reminded the Western public, if only briefly, who these migrants are: fellow humans who love, fear, and hope the same as they do, driven to despair by circumstances outside their control.

This is the case with the titular Hakim. Perhaps it’s the humility of his livelihood that makes Toulmé’s protagonist so relatable: he is not a policeman, a soldier, or anyone in a position of power. He is a gardener who owns and operates a plant nursery near the Syrian capital, Damascus. The eldest of nine children, Hakim inherited a green thumb from his father and developed it into a successful business. What passes for modesty in the West counts as prosperity in Syria: Hakim earns enough to rent an apartment and own an automobile, things so many of us take for granted, acquiring a happiness the decadent among us find fleeting at best.

Hakim, who recounts his story to Toulmé (who, in turn, recounts to the reader), nevertheless describes a country of deep compromise: a beautiful land with a rich history and a warm sense of community, yet burdened by a corrupt and sectarian regime. Though Sunni Muslims make up a majority of Syria’s population, a slim Alawite minority dominates society and government. In a nation under an expansive socialist republic, managerial posts, security ranks, and business opportunities are set aside for Alawites. Syria’s many other sects, from the Druze to Orthodox Christians, must remain content with a low place in the hierarchy. The underlying sense of discrimination is eclipsed by the overt reminders of oppression: routine payments to authorities, the sudden disappearance of a neighbor or colleague overnight, and the watchful eye of suited men who may or may not be the dreaded Mukhabarat (Syria’s secret police).

There is a scene from Hakim’s childhood that conveys the unease beneath everyday life in Syria. He asks his father a simple question: will Syria ever have a president who is not Hafez al-Assad? (Hafez being the late father of the current president, Bashar al-Assad.) “Hush,” his father admonishes. “The walls have ears!” The young Hakim is left confused, trying to find ears on the walls of buildings he passes. The only ears he can spot are those on the Assad portraits that line every street. It’s only later that Hakim understands his father’s reference.

But Hakim, like most Syrians, tolerates life under a paranoid autocracy. There is a “so be it” attitude among the populace, enduring their situation within the narrow social parameters that the state allows. But those constraints grow ever tighter when protests hit Syrian streets.

Though Toulmé sheds light on Syrian history and regional politics in his prologue, Hakim shows no interest in Tunisia’s revolution, the fall of Egypt’s dictatorship, or anything related to the Arab Spring. Up until 2011, what happened outside Syria had little to no bearing on his adult life. His introduction to the unrest comes when a protest occurs near his family home. Hakim’s younger brother embraces the vague idealism behind the protests, boasting that he appears on television. It isn’t long before soldiers and police suppress the demonstrations with lethal force. Worse comes with the regime’s black-clad, muscle-bound enforcers, the shabiha (ghosts), who abduct suspected dissidents into a seeming void of the unknown. In a sense, the disappeared become worse than mere statistics — they become damnatio memoriae, banished from official memory.

Checkpoints, curfews, and random searches become the norm in Syrian life. Still Hakim tries to adapt to this chafing oppression — until he cannot. Hakim is not the one who makes the decision: it’s the state. When soldiers find a mask for insecticides in his car, they arrest Hakim on suspicion of being a rioter. He spends several weeks in a cell with over a dozen other men, enduring one round of beatings after another. It isn’t the beating that leaves the deepest scar on his memory, however; it is the mistrust planted inside him as his torturers list names of clients, friends, and family who they claim have corroborated the allegations of his subversion. Only when one of Hakim’s influential customers intervenes does he regain his freedom. Even a reunion with his family is tainted by hostile seeds planted in his psyche: “Everyone seemed really happy but I thought to myself that, perhaps, one of them had denounced me. And I felt that something in me was broken. I was suspicious of everyone…”

Freedom regained is not normality restored. The army has converted his plant nursery into barracks and confiscated everything on site. Hakim tries — for lack of a better term — to soldier on in Damascus, but his livelihood has been taken from him through no fault of his own. He tries to stay in Syria, hoping to wait out the unrest. He can’t. The disappearance of his younger brother pushes his parents to hurry him out of the country, so as to save at least one of their sons.

It is the community spirit that Hakim loved so much in Syria that allows him to find a roof over his head as he travels the region: a friend in Lebanon, a cousin in Jordan, a former classmate in Turkey. But he cannot escape the ghosts of Syria. Hezbollah works with Syrian agents to detain and interrogate refugees, hoping to identify and eliminate dissidents. In Amman, Hakim is part of an unwelcome flood of Syrians crowding apartments, begging on streets, or competing with the country’s own working class.

It is only in Antalya that he finds any modicum of progress in his refugee life. Antalya is home to a community of Syrian exiles largely segregated from Turks by language and resentment. These exiles include Abderrahim, a once-successful Syrian car dealer who fled the country after repeated extortion by the state. Hakim not only finds friendship in Abderrahim’s family, he finds love and weds Abderrahim’s vibrant and assertive daughter Najmeh. Thus in Turkey our protagonist regains a semblance of family to join him in the pursuit of greater prospects in his next destination: Istanbul.

¤

One can see Toulmé’s chronicle as a spiritual successor to Riad Sattouf’s lauded The Arab of the Future. The latter is an autobiographical account of Sattouf’s youth with his ideologically confused father, Abdel-Razak, a man who becomes absorbed in an ultimately fruitless pursuit of an Arab nationalist utopia. Repeated failures pull Abdel-Razak deeper and deeper into rejection and resentment.

The Arab of the Future depicts the twilight of a midcentury Arab nationalism, al-qawmiya, championed by the likes of Egypt’s Gamal Nasser, Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, and Iraq’s Saddam Hussein. Each sermonized a new order shaped around Arabic identity, socialist governance, and resistance to foreign influence.

Though often espoused by its progenitors as revolutionary, there was an element of restoration behind the vision. Political leaders sought to bring about a reclamation of Arab political and economic identity not seen since the medieval caliphates. In these leaders’ vision, years of inequality — whether religious or financial — would be rectified by a socialist republic, dismantling the old order and carrying out a redistribution. And through large citizen armies, the Arabs would not only secure true independence from Western powers, but also assert their will on the same footing as their former colonizers.

There was, in short, a goal to settle old scores. The inspirational oratory of forward development was eclipsed by fiery exhortations against enemies. Zionists. Reactionaries. The West. Demagoguery, not hope, soon guided the Arab nationalist cause. Unfortunately for its evangelists, Arab nationalism lacked the stewardship to execute its most confrontational objectives. Dreams ended in flames on the battlefield, in places like Chad, Khuzestan, and the Sinai. Besides a loss of national pride, these losses devoured the resources of fragile economies. The remarkable infrastructure development and social advancement that characterized early Pan-Arabist rule gave way to economic stagnation, deepening oppression, and political isolation.

Both The Arab of the Future and Hakim’s Odyssey act as eulogies: the former for Pan-Arabism, the latter for the Spring that came after. Admittedly, it’s too obvious to call the Arab Spring’s own failed ideals ironic. Commentators have long since replaced the notion of spring with that of winter, an apt description for the long and bitter climate that has swept through the region. The notion of a popular, equitable democracy is no closer to the Arab world now than it was a decade ago. Even Tunisia, once the shining beacon of democratic transition, contends with public tumult and an executive leadership centralizing power. So dissipates another wave of revolutionary optimism.

¤

Graphic Mundi has slated the next two volumes of Hakim’s Odyssey for publication this year. Book 2, due out this month, follows Hakim’s journey from Turkey to Greece. Book 3 will close Hakim’s story with his travels from Macedonia to France. (The final publication date is to be determined.)

One suspects that Hakim’s treks will resume beyond Toulmé’s books, perhaps culminating in a return home to his native Syria. If Odysseus could end his odyssey back home and in triumph, let us hope Hakim can do the same.

¤

LARB Contributor

Andrew Montiveo is a writer in Los Angeles. A graduate of film at UC Irvine, he has written for Bright Lights, Cineaste, and The Worcester Journal.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Moments of Grace: On Azar Nafisi’s “Read Dangerously: The Subversive Power of Literature in Troubled Times”

In her new memoir, the author of “Reading Lolita in Tehran” describes her troubled relationship with her father.

A Space Held Against Disappearance: On Diana Abu-Jaber’s “Fencing with the King”

An expansive, polyvocal novel that explores Jordanian American cultural inheritance.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!