That Wacky World of Federal Criminal Laws

Laurie L. Levenson reviews Mike Chase's "How to Become a Federal Criminal: An Illustrated Handbook for the Aspiring Offender."

By Laurie L. LevensonFebruary 23, 2020

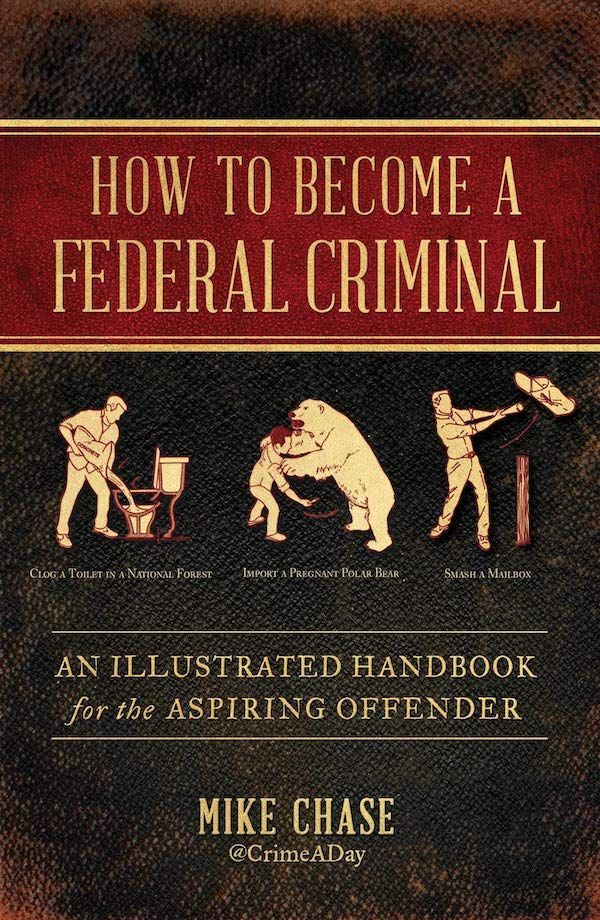

How to Become a Federal Criminal by Mike Chase. Atria Books. 320 pages.

IF YOU LOVE legal trivia, you’ll love How to Become a Federal Criminal. Evidently, the author, Mike Chase, developed the same habit I had as I sat in magistrate court waiting endlessly for the judge to call my case. I would flip through the federal code to find the most obscure federal crimes. Undoubtedly, Chase made his search much more of a science; he has collected a stunning array of bizarre federal crimes that could ensnare the unwary. With humor, illustrations, and a stunning amount of detail, Chase has created the ultimate guide to the wild world of federal criminal offenses. As he shows us, it is practically a miracle that we are not all sitting in a federal penitentiary right now. Both Congress and the regulatory agencies have been operating overtime for the last two centuries, creating federal offenses that seem unbelievable, but are all too true. Thank your lucky stars that you won’t have to learn about them the hard way.

Chase sets the tone for his book with his dedication page. He writes: “This book is dedicated to the United States Congress. You guys are hilarious.” Indeed, such irreverence is deserved. It is positively staggering how many ridiculous offenses are on the books. Of course, you all know that you could lose your security clearance if you tear the tag off your mattress, but try this little test to see if you are really a knowledgeable law-abiding citizen.

Which of the following are actual federal criminal offenses?

1. Impersonating Woodsy the Owl

2. Mailing a threatening letter to the circus

3. Using a falconry bird in a movie that isn’t about falconry

4. Importing a pregnant polar bear

5. Writing a check for under $1

6. Putting antifreeze in medicine

7. Selling pork with a pronounced sexual odor

8. Selling pink margarine

9. Selling a can of asparagus with more than 40 thrips [1] per 100 grams

10. Selling spinach with a two-millimeter caterpillar

11. Pretending to be a member of the 4-H Club

12. Trying to make it rain before telling the government first

13. Injuring a government lamp

Nope. I’m not going to tell you the right answer. That is why you need to read this book. Because you will be amazed by how many brain cells have been sacrificed to enact ridiculous laws in this country.

This would have been a fine book if all Chase had done was catalog the odd federal crimes that have been enacted. But he has done much more. If you are having a dinner party with lawyers or Supreme Court Justices, you can now wow them with your knowledge that it is illegal to walk a dog on a leash longer than four feet in front of the Supreme Court. Just in case you have the urge, you will know to resist the urge to correspond with a pirate. If you don’t know what to say to your next dinner date, impress him or her with your knowledge that “tripe with milk” has to be at least 65 percent tripe. And, if you find yourself in a compromised position, absolutely resist the temptation to detain a seaman’s clothes. Yes, all of these will get you a federal rap sheet.

In fact, Chase itemizes the wide range of federal crimes dealing with animals, money, food, federal property, alcohol, acts on the high seas, and practically everything else that we encounter in our society. I have not been tempted to import a pregnant polar bear, nor do I know how to check whether she is pregnant, but I’m not taking any chances. I’m going to be really nice to all federal officials, even egg inspectors. Not only are they covered by the federal murder statute, but it is also a serious felony to intimidate them while they are inspecting their ova. They might feel special, but the truth is that the laws even protect macaroni products. Yes, federal crimes are everywhere.

While it is fun to learn about these obscure crimes, where the book really becomes interesting is in its discussion of how such laws came about and how the courts have treated them. The explosion in federal crimes seemed to have started with the Pony Express. Long, long ago … before the internet ruled the world … there was the mail service. Congress took the Postal Service, established in 1775, very seriously. In 1792, Congress passed a statute that practically canonized letter carriers. It was a capital offense to steal mail. In fact, in 1830, two men were convicted of mail theft and sentenced to death by hanging. One of them met his maker quickly. However, his accomplice was offered a pardon by President Andrew Jackson. This stalwart mail thief rejected the offer and chose to be hanged instead. As Chase notes, this moment in history might teach us something for today. It is possible to refuse a presidential pardon, no matter what the consequences.

No trivia is too small for our obsession with federal laws. How could we not focus on the Swine Health Protection Act that requires any garbage fed to pigs to be cooked in a garbage cooker with a garbage-cooking permit? Do we really need to know the lawful way to remove a bald eagle from your house? Couldn’t we live without having a law that prohibits feeding an unskinned wolverine to your dog or prohibits clogging a toilet in a national forest? What kinds of problems led to the express prohibition on urinating or defecating in a reading room of the Library of Congress? Thankfully, Chase spares us the history of all of these laws, but it is not hard to imagine the problems plaguing our federal institutions that led to such laws.

The book makes clear that there was one scandal that finally could not be ignored. In his famous book The Jungle, Upton Sinclair exposed the horrors of the food processing industry. Nauseated beyond words, Congress passed the Meat Inspection Act of 1906. I guess telling Congress that deviled ham was “made out of the waste ends of smoked beef that were too small to be sliced by the machines; and also tripe, dyed with chemicals so that it would not show white; and trimmings of hams and corned beef; and potatoes, skins and all; and finally the hard cartilaginous gullets of beef after the tongues had been cut out,” was enough to get them to finally pass some real laws. Sadly, many of our laws are enacted in just such a way. It is only when ongoing practices are exposed and the public cannot stomach them any longer that the legislature or the agencies react.

As noted by Chase, the flood of curious laws was the result of at least two historical developments. First, Congress began delegating its lawmaking authority in the late 1880s and agencies went wild. But, as Chase candidly admits, Congress passed a bunch of criminal statutes on its own. I guess that was its way of proving that it was doing something. Perhaps it is not such a bad thing when Congress is not pumping out legislation.

And, given the broad scope of crimes, there is a serious point to be made here. Because 97 percent of all persons charged with federal crimes plead guilty, the proliferation of federal offenses puts us all at risk, especially if prosecutors don’t use keen prosecutorial discretion. In a more stoic moment, Chase lets the real message of his book be known:

But if there’s one thing to take away from this book, it’s that you should never, and I mean never, underestimate the government’s power to put you in prison for something as simple as bringing a theatrical chicken — or any performing poultry — back from Mexico without an up-to-date health certificate.

Be careful out there.

We live in odd times. As the nation struggles to define “high crimes and misdemeanors,” one wonders whether anyone has considered the exhaustive list of crimes Chase has compiled. If bribing a foreign leader to investigate political opponents doesn’t make the list, perhaps “offensive personal hygiene” in a federal building might.

After reading this book, one might be tempted to laugh and shrug off the obscene number of federal crimes as just irrelevant historic artifacts. However, there is a serious point to be made here too. With so many laws on the books, there is tremendous power in the hands of those who make prosecutorial decisions. Judges can, and have, struck down some laws as too vague or contrary to the strict language of the offense. However, leaving antiquated laws on the books poses a risk that the unsuspecting could be dragged into the criminal justice system.

Laws also have the power of sending damaging political messages. There was a time when government buildings were open to everyone. Scores of people showed up to help Andrew Jackson eat a 1,400-pound wheel of cheese at the entrance to the White House. Today, any unauthorized visit will land you 10 years in prison. Our government leaders have become more insulated and removed from the American public.

Old laws have been used to perpetuate stereotypes. For example, the Immigration Act of 1907 perpetuated the image of stowaway immigrants as “idiots, imbeciles, feeble-minded persons, epileptic, insane persons […] or polygamists.” In language that sounds dangerously familiar, Frederick A. Wallis, the commissioner of immigration for the State of New York, decried immigrants as a “menace that threatens the safety of the country.”

Even when we pick our government cartoon characters who are cloaked with the protection of criminal laws, we have previously selected the image of “Johnny Horizon.” He is the symbolic outdoorsman who wore no badge or uniform, but dressed as the consummate outdoorsman and was the symbol of the Bureau of Land Management. Impersonating him could be a federal crime. Not until Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg coauthored a report for the US Commission on Civil Rights entitled “Sex Bias in the U.S. Code” did the government note that male figures dominated the mascots chosen by the government to represent the consummate American. The subliminal messages of the laws — including criminal regulations protecting government mascots — can have an impact on our nation.

Chase’s book is a fun and easy ready. He has made a niche as a writer by compiling our country’s “countless weird, esoteric, and, some would argue, unnecessary federal crimes.” While his book is lighthearted, his message is serious and echoes concerns raised by some of the most thoughtful scholars of criminal law. In 1959, Lord Devlin warned in his famous work on “The Enforcement of Morals” about the dangers of overcriminalization. Since then, other icons of criminal law — from Professor Sanford Kadish to H. L. A. Hart — have opined on the dangers of using the criminal justice system to address all of society’s problems. The first step in addressing these dangers is to recognize the scope of the problem. Chase’s book opens our eyes. Federal criminal laws are omnipresent. Consider yourself lucky if you are not (yet) a federal criminal.

¤

¤

[1] Extra points if you know what a “thrip” is. Suffice it to say, it is not something you want in your food, but is tolerated by our food inspectors so long as sellers keep their numbers down.

LARB Contributor

Laurie L. Levenson is a professor of law and the David W. Burcham Chair in Ethical Advocacy at Loyola Law School, Los Angeles.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Century of Fighting for Civil Liberties

Stephen Rohde reviews "Fight of the Century: Writers Reflect on 100 Years of Landmark ACLU Cases."

“We the People”: A Guide for the Perplexed Liberal

Erwin Chemerinsky's "We the People" is a rallying cry for progressives to get out of their funk.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!