Tell Me I Belong Here: On Charif Shanahan’s “Into Each Room We Enter without Knowing”

Natalie Eilbert reviews Charif Shanahan’s new collection, “Into Each Room We Enter without Knowing.”

By Natalie EilbertAugust 24, 2017

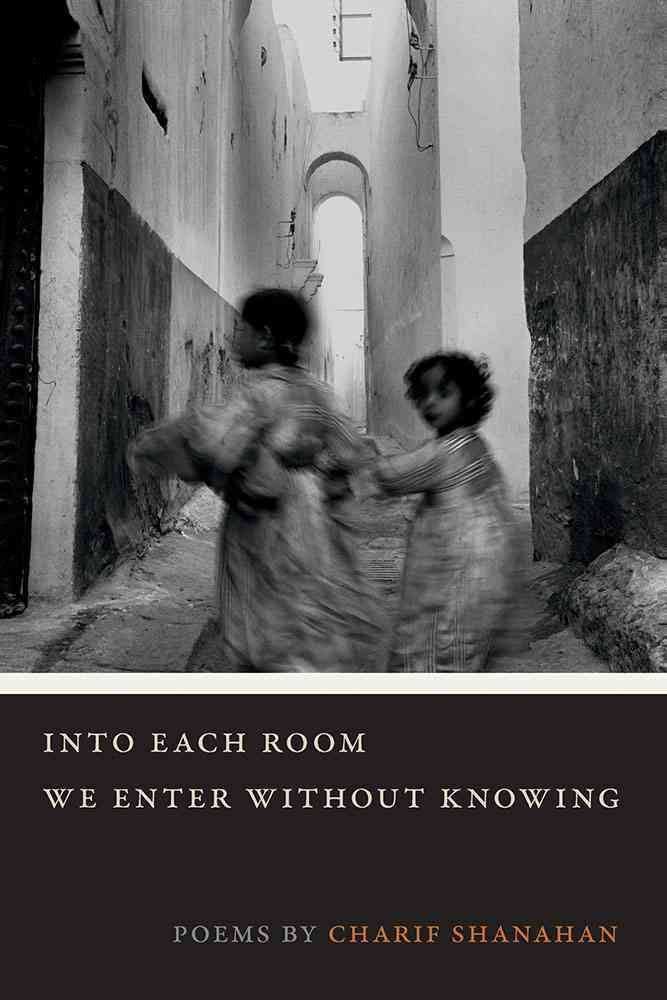

Into Each Room We Enter without Knowing by Charif Shanahan. Southern Illinois University Press. 96 pages.

“THE BLACKSTART IS a confident species,” the Wikipedia entry on blackstarts explains, “unafraid of man.” The blackstart also perches on the sturdy lines of Charif Shanahan’s debut poetry collection, Into Each Room We Enter without Knowing. It is a bird indigenous to North Africa, as well as to areas in the Middle East and the Arabian Peninsula — primarily in their desert regions (“white as his desert’s sky”). It acts as a singular agent, a harbinger of political strife (“‘This Arab spring,’ // my friend continues, my friend stops … / ‘Yes,’ I say, thinking of the blackstart // somewhere in a baobab by now.”), ineffable simplicity (“a single blackstart lands on his knee”), a color activated by time’s darkness (“A blackstart bathes / in the deep shade of the lagoon, / six toes sinking into the mud. // There is hope in the past.”), and an aside to a hard conversation between speaker and father about the love that created Shanahan’s Irish-American–Moroccan mix (“A blackstart lands on a branch above the man outside; the tree — I don’t know what kind it is — is leafless in summer”). It is not difficult to see the patterns that swarm Shanahan’s tangled negotiations of selfhood, and these patterns possess a certain and distinguishable imagistic constraint: black, white, gray, brown. Like the blackstart, they appear and fly off quickly, leaving behind a gradient landscape that is both home and a lost circuit in Shanahan’s memories. It is no coincidence, then, that the blackstart is decisively North African, its migratory path a steady arrow through the Arabian Peninsula. The blackstart’s natural origins are a source of tension as much as intrigue for Shanahan.

When I first Googled it (I had never heard of the species), “blackstart” showed another meaning: a blackstart restores electric power without relying on an external transmission network. In other words, it must find another source of energy to regenerate the city. Shanahan’s spectacular poetry does this — perhaps unwittingly, it seeks to illuminate his cast of cities through unconventional means of conduction. Like the bird, the speaker’s many voices probe the desert, navigating distances. Like regeneration, the mind behind this collection is a spark that can relocate us in the rooms we’ve been wandering through in the dark all along.

Even from the beginning, Shanahan promises this will be a book preoccupied by makers. From the first line of the first poem, “Gnawa Boy, Marrakesh, 1968,” such divine encounter proves fatal: “The maker has marked another boy to die.” The initial meter, near-perfect iambic pentameter, does not last; rather, Shanahan establishes formalities only to see how they might wrinkle and bruise under his spell: neat and knitted couplets conclude with a single line (“the Alps close behind her,” a memorable example); lacunas break up uniform line lengths in the title poem, “Into Each Room We Enter without Knowing” and elsewhere; the longer poem “Your Foot, Your Root” marries prose sections with single lines and indented couplets with strikethrough text, conveying a difficult passage. That initial poem sets an unshackling precedent, even as it maintains a unifying shape. Death and life vacillate, the lines of body blur in such a way that life under the skin is as improbable as death under the skin:

His thin body between two sheets,

Black legs jutting out onto the stone floor,

The tips of his toenails translucent as an eye.

Gray clumps of skin, powder-light,

Like dust on the curve of his unwashed heel

And the face, swollen, expanding like a lung.

At its center, the sheet lifts and curves:

His body’s strangeness, even there.

One palm faces down to show the black

Surface of hand, the other facing up

White as his desert’s sky.

It is as if the speaker sees the body not as dead but simply incapable of further life. This body, has it become alien, or was it always so? To describe the toe, here is an eye. To describe the skin, here is the dust that collects on the heel. The face, a lung. The pale palm, the white of an altogether different associative order. In espousing the parts anew, the body becomes less body. The black boy, in death, becomes recognizable only in how he is shaped by parts that do not align with his forced otherness.

The light-skinned women in this poem further complicate this. They have “gathered in waiting: / No song of final parting, no wailing / Ripped holy from their throats.” The contrast here is stunning. They are a group who refuse the body rites. They do not sing; they burn in the sun. They do not mourn the loss of the boy. The tone of the book is clear. Even there — in that room, in that country, in that death, the black hand and the white palm together and separately facing up — his body’s strangeness.

The poem ends but it hasn’t concluded, because the penultimate poem before the final section in the book picks up where “Gnawa Boy” leaves off on the line “They do not hit themselves in grief —.” “Haratin Girl, Marrakesh, 1968” opens with “— As the room is emptied of the boy’s body, / she watches through a hole carved into a wall of stone.” The Haratin girl is also strange, but it isn’t for the body that she is strange — it’s her presence as witness: “where the girl / stares hard, her eyes strange and dark.” It is significant that before we see the girl looking at the lifeless body through a hole, we are made to see the exchange of white and black hands — both on the boy and pressed into the boy by the living women — the violence and love engendered by such contact.

The bodies throughout the book are not dead — they are alive, flashing sexual energy in secret. If there is a lover present, desire is this irrevocable loneliness, the spiritual crisis of intercourse and traveled-through cities. (“Outside two boys hold hands and squint / At street signs they cannot see past.”) We are beholden to such intimacies, graciously, by Shanahan himself.

their pale hands tentative to touch it, grasping not the elbow or knee,

not the ankle or neck, but the rounded softnesses —

buttocks, side of torso — and the smallnesses — two fingers,

an ear, a tuft of rough hair — as if to carry him without touching him

And like the light-skinned women initially charged with the body, negative capability documents the tradition of the dead — “She does not begin the procession through the old city, / she does not pour the bathwater, or warm it, or salt it.” She will be yelled at, sexualized and bruised by her streets, and she will run, grasping toward a mother’s future for the “olive hand of a child, or children, not yet born —.”

¤

In trauma, dissociation is a tool in coping with the grief our bodies and minds have endured. In this book, dissociation is critical for how soon the maker becomes the father. In two early poems, “Trying to Speak” and “Plantation,” we see a father wielding a gun and then a hammer over the mother, but we do not see the weapon any more than we see a matrix of other imaginings on the part of the child. “Plantation” tells us, “I was clear enough to see inside // The cracked plaster: / A river delta, fractured, // Branching off and becoming / The sea …” It is not a father bringing down a hammer but the fissure in the wall, a transaction spelled out by the psychic waters of a boy split in two: in a line, dead white presidents (12) on one end; on the other, black women floated on slave ships. The wall and the fissure of the wall; the structure and the split that ravages its surface; the white man on top of the black woman and their child. Later in the book, Shanahan will find himself before two mirrors, his reflection again split as he tries to push a difficult discussion with his Irish-American father over lunch: “I stand between two mirrors. I look hard behind me into each of the untold cascading reflections, as if for variation, or a center, but they only grow smaller and less precise the deeper I look.” That this sequence is delivered in prose makes it especially urgent.

Chiasmus, too, can be part of dissociation. Its usage speaks to an exasperation, a resignation, a bright strange insistence. We get this chiasmic work at the end of “Self-Portrait in Black and White,” though prior to that, we experience leaps that are distinctly stripped of metaphor: “A fire engine is a backpack and my father. / Dollar bill is headscarf, star and crescent.” Shanahan tells us, “The years form a mythology I can almost explain.” The mythology of country is one kind of explanation; that of capital exchange, another. The poem can almost explain to us before the chiasmic punch: “Now, stirring milk into my coffee with a bent spoon, / I stir milk into my coffee with a bent spoon.” Before the mythology can be explained, one must endure it, be inside it, encounter the combination of black and white and drink it into the body, swallow it whole.

The mother, while often subject to the violent whims of the father, is not inactive. She fastens her bathrobe after a gun is pressed to her neck in bed, thoughtful enough to ask the speaker, a child at this point, to defrost the chicken. She protects the child with both arms against the father’s hammer. She faints upon seeing a butcher cutting the tongue from a lamb’s head only to right herself and leave “as when Muhammad awoke in the night desert” (a blackstart will appear before him). She is black, but she disavows Shanahan’s blackness. She puts dinner away, “singing / to me about a country she once knew.” In “Clean Slate,” she mistakenly drinks bleach as a young girl, thinking it is water. With the chemical so deep in her system, trace amounts cannot be removed. The poem is a genius display of Shanahan’s rhetoric, and the bleach requires no additional explanation. Lit by these traces of bleach, the speaker tells us on the phone with her that he is “beginning to understand that I am African,” only for her to respond, “Now how can that be, child? How can that be?”

Throughout the collection, Shanahan describes a dislocation within himself, while those same anxieties run rampant in the external world. And we know the brutality of systemic racism all too well. Sometimes, the titles alone give us that explicit dislocation, as in the poem, “At L’Express French Bistro My White Father Kisses My Black Mother Then Calls the Waiter a Nigger,” as in the final poem “Whiteness on Her Deathbed.” His poem “Wanting to Be White,” after Jorie Graham’s “Wanting a Child,” shares the trope of water as a means to grieve individual loss. Graham opens “Wanting a Child” with: “How hard it is for the river to re-enter / the sea”; Shanahan, by contrast, opens “Wanting to Be White” with: “How easy for the waterfall to turn back / into the river.” Different from other poems in the book, and perhaps due to its lineage, the desire of whiteness is maintained through simulacrum, stripped almost entirely of ego, save for an italicized phrase from Graham (“Sometimes I’ll come this far from home / merely”) — the waterfall returns to its river state easily, but for the river, the circumstances are quietly restrained and existential. Like Shanahan’s relationship to self, there is a system in place that establishes two dramas, the ease of whiteness amid a forced complicity of that whiteness, announcing his blackness to his parents who don’t understand his blackness — the waterfall crashing into the riverbed, the riverbed needing but to flow again, turning river, repeating its violent fall:

… The river,

taking its motion from the surging above, urges,

persists, knowing

no way out, no way to extract

itself from its own circular endurance

tenacious, whole, singularly minded

until it carries itself back to its own source.

Dirty glass is another continuous image in this book. In Solmaz Sharif’s Look, she says of the taxonomy of war, “Let me LOOK at you in a light that takes years to get here.” Shanahan (who quotes Look’s credo, “It matters what you call a thing”) associates dirty glass with travel, a window scoring landscapes and figures into sizeable memories. But dirty glass is specific, the way the light in war is specific — both use it to implore difficult information. For Shanahan, his complicated identity begets complicated relationships — in the case of his parents, but also in the case of his romance with men. The dirty glass is a logic in that it draws meaning to the other side no matter what the viewer feels, no matter how he sees that other side. Dirty glass stands as the erotic in-between, as in “[t]he dirty glass window between us, / I turn to exit the platform.” But beyond that, the glass deceives. Elsewhere, it appears as a train window through which a black Italian woman in Ticino looks “out through dirty glass / at one country turning into the next.” It distinguishes its information, but barely so — identity is as tricky, deceptive in its simplicity of facts: white father, black mother. This is evident in “The Most Opaque Sands Make for the Clearest Glass,” which begins “The dark matter / Turned its face to mine,” and ends “How / Can she sit there and say, Child / I am not, we are not — / In spite of — no, inside of / The dark fact of her body?”

However, it is not until the two final movements in the book — one toward his father and the other toward his mother — that we see Shanahan empowered enough to directly address his troubled politics. He opens “Your Foot, Your Root” plaintively: “At the famous deli on Houston Street, I sit opposite my father. Stop causing trouble, he says, always asking questions about the heavy shit, though I think I’m only trying to live.” The effort of auxiliary in “I think I’m only trying” has a heartbreaking tone, the accusation that minimizes one’s entire crisis of identity into that of a nuisance. The poem travels from this lunch to a flash of Shanahan’s young father to Shanahan’s Omi identifying the pretty one in the music video of “The Boy Is Mine” by Brandy and Monica (“The words she does offer are hada sweena, hada khiba, pointing at the TV screen: That one is beautiful, that one is ugly. They are roughly the same complexion. Brandy wears her hair in braids, Monica hers bone-straight, so I do not need to ask how she means what she means”) to a lecture on atrocities in Germany and back to lunch, back to the origins.

Shanahan is a master of shaping his dialectic through lyrical groundwork. He will occasionally come to a question-and-answer format, reminiscent of W. S. Merwin’s “Some Last Questions.” The form of the couplet serves to clarify and pronounce his dislocation on the final page of this poem:

So do you have a black wife?

Yes.

Does it matter?

No, Or it depends who you ask.

Can the thing matter and not matter at once?

Not to the same person.

Are you sure?

The face can be a wound and a shield.

So many threads in his collection come together only to fray and come apart in his hands. But he wants us to gaze into the used material, to see that even in the circles of care and foresight, the damage is there, handled or not. And like the Haratin girl seeing the Gnawa boy’s body 60 pages later, we see at the end of the book the same curiosities in “Wanting to Be White.” The water, forced into river and fall, “knowing / no way out,” returns at the end of “Your Foot, Your Root” in the form of two final questions (the last unanswered) from Shanahan to his father: “What do we lose? / Much. / Where is the way out?” When we gaze at the mother’s moribund body in “Whiteness on Her Deathbed,” we adopt a kind of question and answer, an alternating indentation. The light-skinned women lifted the softnesses of the boy’s body in 1968. Now, Shanahan is tired, observing the coming of death, listening to the struggle of breath. Unlike the women who do not touch where they do not have to, Shanahan ties the cloth around her chest, binds the feet, and is moved by the pages of the Qu’ran flapping in the wind. In this body, through which we have seen him render selfhood, he will honor his mother’s body, return it to its source. In the final grammatical turn, wind rustles the Qu’ran pages, the black body is cold beneath his hands. As the river flows, as the dirty glass gives us the figure standing away from us, as the confusion of the body refuses to be brief, we are promised nothing — not even ongoingness. Shanahan is calm and potent in his pain, having arranged the body perfectly.

¤

LARB Contributor

Natalie Eilbert is the author of Indictus, winner of Noemi Press’s 2016 Poetry Contest, slated for publication in late 2017, as well as the debut poetry collection, Swan Feast (Bloof Books, 2015). She held the 2016–’17 Jay C. and Ruth Halls Poetry Fellowship at University of Wisconsin–Madison. Her work has appeared in or is forthcoming from Granta, The New Yorker, Tin House, The Kenyon Review, jubilat, and elsewhere. She is the founding editor of The Atlas Review. Photo by Emily Raw.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Will You Join Me in Taking Up the Body?: On Sara Uribe’s “Antígona González”

Lara Schoorl finds inspiration in “Antígona González” by Sara Uribe.

Devastating Remaking: On Melissa Buzzeo’s “The Devastation”

Maria Damon appreciates “The Devastation” by Melissa Buzzeo.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!