A Tale Which Must Never Be Told: A New Biography of George Herriman

Ben Schwartz reviews Michael Tisserand’s new biography of George Herriman, creator of “Krazy Kat.”

By Ben SchwartzMarch 18, 2017

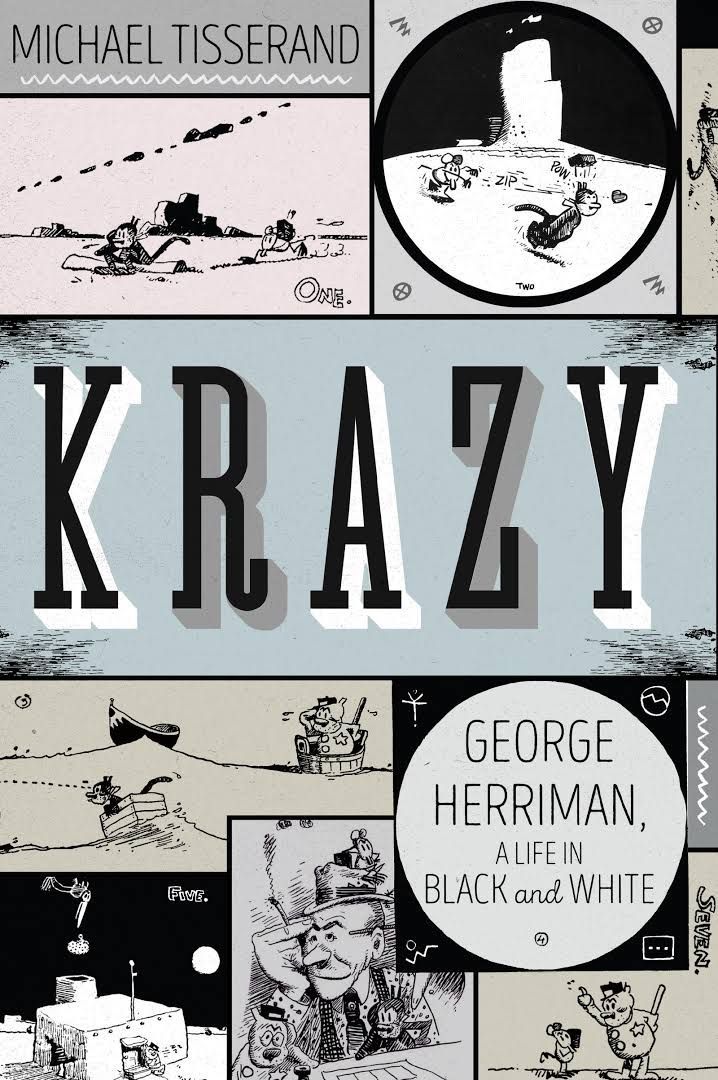

Krazy by Michael Tisserand. Harper. 560 pages.

ON MARCH 4, 1913, Woodrow Wilson took the oath of office and became our 28th president. While we remember Wilson for his internationalist foreign policy and progressive labor laws, he was also the first Southerner elected since the mid-19th century, and his racial policies reflected it. Wilson saw Jim Crow as the necessary remedy to the aftermath of the Civil War. As president, he normalized his revanchist views from the White House by expanding segregation of federal workers. Not surprisingly, 1913 also saw a rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan. An excerpt from Wilson’s revisionist writings proclaiming the Klan “a veritable empire of the South” even appears in D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, a box-office smash which Wilson personally screened at the White House, the first American film ever shown there.

In that reactionary atmosphere, on October 28, 1913, in the New York Evening Journal, William Randolph Hearst debuted a new comic strip, Krazy Kat, by one of his favorite cartoonists, George Herriman. It starred Krazy, an androgynous cat in love with Ignatz, a brick-throwing, cat-chasing mouse. They lived in Coconino County, Arizona, desert mesa country, and Herriman shifted their backgrounds panel-by-panel — night to day, day to night, mountain to desert to town to river — with no rhyme or reason. They spoke in a patois of slang, Elizabethan English, Yiddish, Spanish, French, and tossed off literary allusions. When asked once about his basic upending of the natural order of cats, mice, dogs, time, and space, Herriman summed up his Weltanschauung: “To me it’s just as sensible as the way it is.”

Krazy Kat’s whimsy caught on quickly in the Age of Wilson, and its large and devoted fan base ranged from high society to poets to school children to the president himself. What none of them knew then was that George Herriman was black. He passed for white most of his life. And what we can only see now, thanks to an authoritative new biography of Herriman by New Orleans historian Michael Tisserand, is that, as far removed from social commentary as Krazy Kat may appear, race was as much on George Herriman’s mind as the president’s.

¤

George Joseph Herriman was born August 22, 1880, at 348 Villere Street, in New Orleans’s Tremé district. His family dated back in the city to 1816 as free blacks, business owners, and civil rights activists. Herriman’s grandfather helped organize a petition hand-delivered to President Lincoln on March 12, 1864, asking for his support in giving blacks the vote in Louisiana. But, after the Civil War, the Herrimans discovered that their free legal status in the antebellum period meant little to bitterly defeated whites. As Reconstruction’s federal protections ended in 1877, the Herrimans found themselves marginalized in New Orleans as people of color. So they left for Los Angeles, where, in 1886, they reinvented themselves as white.

From age 10 through high school, Herriman attended St. Vincent’s College, which did not admit blacks. He did well scholastically, especially in Christian doctrine, English, and Latin (Herriman had a knack for languages: he would later learn Spanish, German, and Navajo). At St. Vincent’s, he was exposed to two key influences, Shakespeare and Cervantes, both of whom he quoted in cartoons throughout his life. After graduating, he found work as a classified ad illustrator at the Los Angeles Herald, and spent the next 15 years shuttling between Los Angeles and New York cartooning and illustrating for papers in the Hearst and Pulitzer chains. Before Krazy Kat, Herriman tried several strips — Professor Otto and His Auto, Acrobatic Archie, Baron Mooch, Mary’s Home From College — but none were hits. In that era, cartoonists were regarded as visual reporters, and in his journeyman days Herriman was sent out to liven up sections with sketches and wisecracks about anything from John McGraw’s New York Giants to the Wilson-Taft-Roosevelt election night returns in downtown Los Angeles. (Hearst’s Evening Herald flashed the results on a screen for the public, and Herriman improvised sketches and political commentary for the crowd.)

Slight of build and swarthy of complexion, the most consistent trait friends and colleagues recall about Herriman was his shyness. “Personally, Herriman is so modest and self-effacing that he is almost annoying,” Damon Runyon wrote of him, “He talks very little, and then in a soft, low tone.” The cartoonist Bobby Naylor described him as “[a] person you would want to like if you could just figure out how to ‘get to’ him.” By 1906, after too many jokes from co-workers about his kinky black hair, he took to wearing a hat in public at all times, indoors or out. He claimed to be Greek, and to hail from California rather than New Orleans. Even his wife Mabel, who he married on July 7, 1902, may not have been privy to his secret: “There is no way to know if Mabel Herriman was aware of her husband’s racial heritage or if she would have cared,” Tisserand writes. They eventually settled in Los Angeles with their two daughters.

Herriman was so adept at keeping his secret that no one actually knew his race until a comics historian sent away to New Orleans for his birth certificate in 1971, 27 years after his death. Tisserand is one of the first scholars to show us how Herriman’s closeted life, especially his conflicting desire for acceptance and fear of exposure, affected his work. Another problem has been that the bulk of that work is out of print and inaccessible. This is hardly unusual: a cartoonist’s work in Herriman’s era was usually discarded the day it was published. We had yet to become a nation of collector archivists, obsessively preserving every ephemeral piece of our pop culture. Today, only the Krazy Kat Sunday pages are in print, one in seven days of Herriman’s work, along with a smattering of miscellaneous daily strip collections.

One of the major feats of Tisserand’s research was to simply collect Herriman’s 1896–1944 body of work so that he could read it, and he has made some remarkable discoveries in the course of his research. In Musical Mose, an early gag strip about an African-American musician, Herriman offers a February 16, 1902, strip in which Mose poses as a bagpipe playing Scotsman for two Scottish ladies. They love his music, but once they discover he’s black, they violently pounce on him and beat him. Herriman repeated the gag with Irish and then Italian characters, all with the same result. “Herriman might not have publicly identified himself as a black man,” Tisserand writes, “but reading Musical Mose more than a century after its first appearance, it is hard not to interpret the comic as a sign that Herriman could not fully, in Du Bois’s words, ‘bleach his Negro blood in a flood of white Americanism.’”

Another of Tisserand’s revelations is that Herriman introduced Krazy Kat while on the sports beat. It was Herriman’s solution to the cartooning problem of how to depict black boxers like Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight champion of the world. Some cartoonists demeaned them in minstrel style, others as brutal savages. Herriman’s “funny animal” approach came straight from the comics, presenting black fighters as black cats, as big and ferocious as a panther, but with Krazy’s now familiar, friendly face. Not long after, Hearst put Herriman back on the funny pages with The Family Upstairs, a situation comedy about a New York family living below the noisiest neighbors in the city, and Herriman reintroduced Krazy as the family’s cat. Soon, a white mouse joined the cat. When gags involving the two proved popular in their own right, Herriman was told he could spin them off into their own strip.

Krazy Kat debuted October 28, 1913, in Hearst’s New York Evening Journal, the year of the Armory show, a landmark exhibition of modernist art co-organized by Herriman’s close friend and fellow Hearst cartoonist, Walt Kuhn. His own work was, in its way, no less avant-garde. Modernists quickly embraced Krazy. At Harvard, T. S. Eliot and e e cummings (who papered his dorm room walls with Krazy strips) were instant fans. Critics Gilbert Seldes, H. L. Mencken, Deems Taylor, and Edmund Wilson (a Herriman pen pal) soon followed.

The ruling class adopted Krazy, too. When Colonel John Jacob Astor IV named his dog Ignatz, Herriman let Ignatz thank him: “That’s just like those millionaires, they glom every thing in sight and reach out for more.” President Wilson was known to enjoy Krazy Kat before his grim cabinet meetings during World War I. Like most people, he never suspected political or social commentary in Krazy and Ignatz. And that’s how Herriman wanted it. After all, he had a secret to keep. “[M]ost people who like that work of mine are people who supply their own ideas,” he said, disavowing any serious commentary.

And his fans did have a lot of ideas. Cummings saw Krazy Kat’s love triangle as a “meteoric burlesk [sic] of democracy.” Later Jack Kerouac, in a list of antecedents to the Beat Generation, would connect “the inky ditties of old cartoons (Krazy Kat with the irrational brick)” to “the glee of America, the honesty of America.” That sort of abstract, archly conceptual talk has long dominated the conversation about Herriman. “In a comic strip of this sort,” Umberto Eco wrote of Krazy Kat in 1985, “the spectator, not seduced by a flood of gags, or by any realistic or caricatural reference, or by any appeal to sex and violence, could discover the possibility of a purely allusive world, a pleasure of a ‘musical’ nature, an interplay of feelings that were not banal.”

But now, in the light of Tisserand’s groundbreaking book, Krazy Kat can finally be read as a work by an artist rooted in a specific time and place with a specific point of view of that time and place. What was once a deeply coded conversation about race now appears obvious. “Oy, it’s awful to be lidding a dubbil life — like wot I am,” Krazy once sobbed (November 24, 1919). On February 11, 1917, Joe Stork — a “purveyor of progeny to prince & proletarian” — tells Krazy how he personally delivered all the babies of Coconino County and left Krazy’s litter in a washtub in a haunted house. Naïvely, Krazy celebrates her true origins, and Coconino’s citizens immediately exile her. “Oh, that us aristocrats has gotta breathe the same air,” sniffs Kolin Kelly, the brick maker. “Them bumpkins should be kept down,” says Walter Cephus Austridge. But on Sunday, April 20, 1919, Herriman reveals Krazy’s royal ancestry, tracing her line back to Kleopatra Kat of Egypt. As Kleopatra tells her daughter, “Remember, Krazy my child, you are a ‘kat,’ a kat of Egypt, and so you hold the respect of the world — let no menial transgress.”

Krazy Kat is hardly an autobiographical strip. It’s not Maus. But finally having a biographical context for Herriman’s life adds a new layer of interest to reading him. Within Coconino’s shifting locales, days and nights, and genders, we can now glimpse traces of Herriman’s hidden life. It is “a tale which must never be told,” as Herriman wrote the day of Krazy’s expulsion from Coconino, “but which everyone knows.”

¤

Ben Schwartz is currently working on a history of American humor set between the two World Wars.

LARB Contributor

Ben Schwartz has written jokes for the 84th Oscars, Letterman monologues, Wits, as Suck.com’s Bertolt Blecht, and his screenplay Home By Christmas is on the 2011 Blacklist. As a journalist and critic, he has written for The New Yorker, Lapham’s Quarterly, Bookforum, The Baffler, The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, and is currently a judge for the Los Angeles Times Book Prizes for graphic novels and comics. He is currently working on a history of American humor set between the two world wars. He lives in Los Angeles and can be followed on Twitter at @benschwartzy.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!