Sustained, Energetic Engagement with the Object: On Becca Rothfeld’s “All Things Are Too Small”

Kenneth Dillon reviews Becca Rothfeld’s “All Things Are Too Small: Essays in Praise of Excess.”

By Kenneth DillonMay 29, 2024

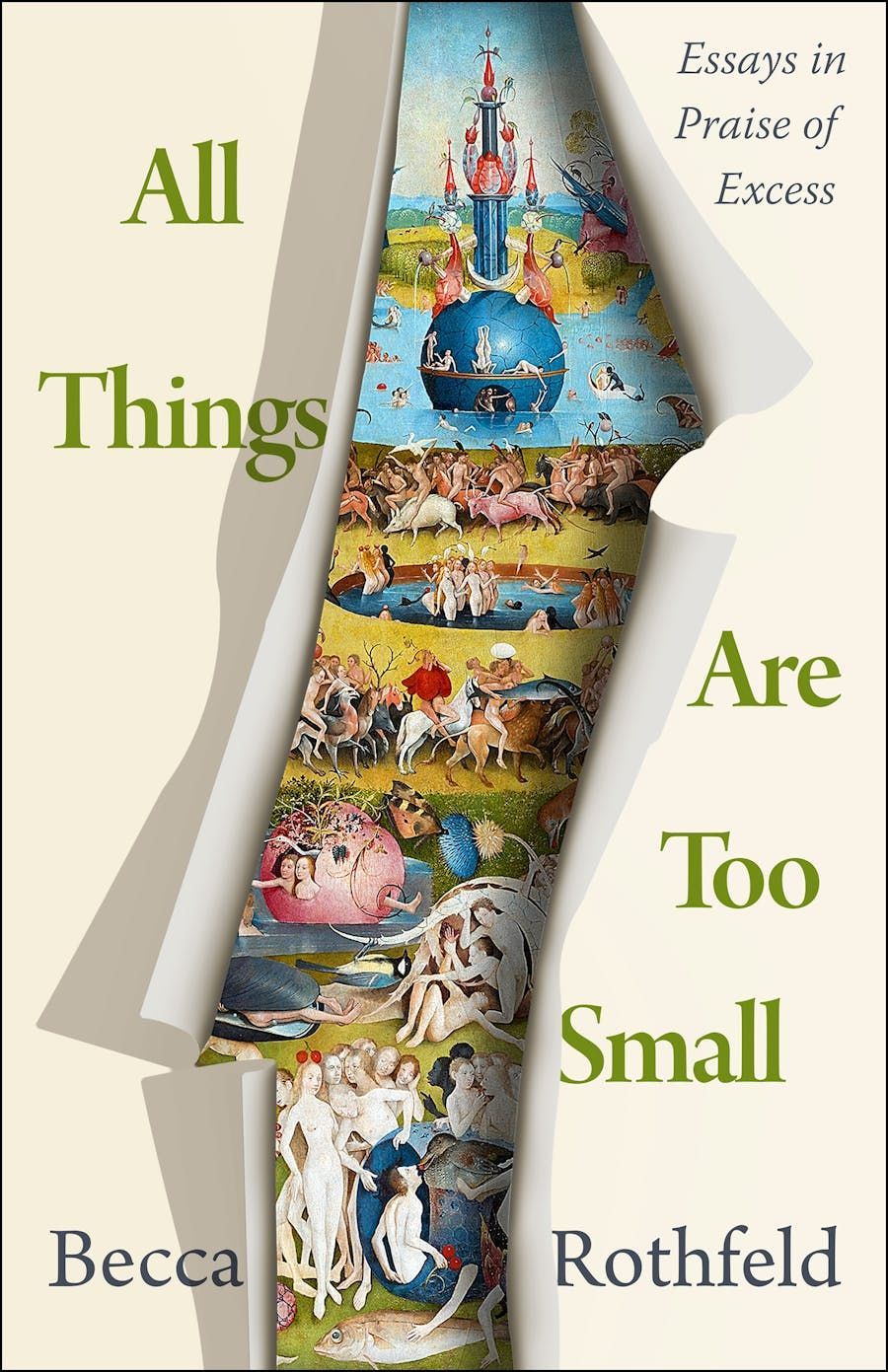

All Things Are Too Small: Essays in Praise of Excess by Becca Rothfeld. Metropolitan Books. 304 pages.

IN AN INFLUENTIAL essay on the aesthetic values of minimalism and maximalism in literature, the late John Barth jokes that “[t]he oracle at Delphi did not say, ‘Exhaustive analysis and comprehension of one’s own psyche may be prerequisite to an understanding of one’s behavior and of the world at large’; it said, ‘Know thyself.’” But Barth, whose own novels are often long and complex, isn’t handing a victory to his more frugal peers. Instead, his essay argues that both minimalist and maximalist works of art can be appreciated and judged on their own terms—that each form has merit.

Becca Rothfeld isn’t so sure. In a literary climate that seems to champion terse yet purportedly serious volumes like 2023 novels The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor and The Vegan by Andrew Lipstein—a world of words in which brevity has, ostensibly, come to represent the soul of lit—Rothfeld goes against the suddenly too-fine grain, issuing what The New York Times called a “plea for maximalism.” Of course, the new Washington Post nonfiction critic’s debut collection All Things Are Too Small: Essays in Praise of Excess (2024) goes well beyond aesthetics, literary or otherwise. Readers who have followed Rothfeld’s bylines from The Baffler and The New Yorker to The Point (where she’s also an editor) will expect her to resist the pedestrian thumbs-up, thumbs-down review format and instead use the books, films, and experiences under consideration in All Things Are Too Small as launch pads for provocative arguments about bigger issues. They won’t be disappointed.

A philosopher by training (she calls herself a “possibly eternal PhD candidate” at Harvard), Rothfeld is skilled at drawing on markedly different perspectives and contexts to build a broad, cohesive argument. Over the course of a dozen essays, she treats the cinema of David Cronenberg as seriously as television police procedurals, while Marie Kondo’s war on clutter receives as much consideration as the philosophy of John Rawls and Amia Srinivasan. Because, while many think aesthetic values grow out of moral ones, Rothfeld suspects the opposite may be true: we don’t judge to be beautiful that which confirms our existing moral views; we discover serious moral positions embedded in beauty. Bearing this in mind throughout her collection, Rothfeld doesn’t want to convince her reader of any particular stance as much as she wants to evangelize a broader critical orientation—one defined by sustained, energetic engagement with the object.

For example: Reading Norman Rush, Rothfeld writes, “I want to be reading Mating constantly; I want to have been reading Mating forever, but always for the first time; I want everything in my life to be Mating and nothing but Mating, including this essay.” In almost identical terms, Rothfeld writes that when she and her husband were first dating, whenever they were near each other, her body “wanted to be filled and then emptied.” She elaborates that, “moreover, it wanted to have never wanted anything except to be filled and then emptied and then filled again, for there was no way that it could be filled to its satisfaction without having been filled forever, beginning before it had any notion of what it would come to hunger for.” That is, Rothfeld approaches Mating and fucking with equal zeal. The fact that both Rush’s novel and her then-boyfriend warrant her perpetual return is evidence that, for her, they contain something mysterious, euphoria-inducing, and important—even if it’s ambiguous and thus difficult to describe.

¤

Sheer enthusiasm doesn’t override the need to explain the link between judging art (or beautiful experiences) and judging people. For that, Rothfeld turns to Rawls’s landmark treatise on ethics, A Theory of Justice (1971), the influence of which she finds everywhere she looks. Rawls famously argues that justice depends on fairness: each person is entitled to as many civil liberties as can be guaranteed for all. To maintain such an arrangement, Rawls assumes that whatever liberties are denied are denied for the general welfare, and that everyone has an equal opportunity to participate in the administration. Perhaps his text’s best-known thought experiment is the “veil of ignorance,” which asks us to imagine we could temporarily give up our identities and design a political system devoid of bias or any kind of vested interest—thereby following the doctrine of egalitarianism.

For her part, Rothfeld considers egalitarianism a fine stance to assume in the legislature or at the polls. Where it won’t serve us so well, she suggests, is in other areas of life. Rothfeld argues that “[t]he logic of justice, proper to the political and economic domain, has infused the whole of contemporary existence,” observing that “[w]hile economic disparities remain fundamentally intact, we insist on equality in love and art, on order and proportion in our minds and houses.” When did the spillover from questions of politics and policymaking to those of creation and care occur? Rothfeld doesn’t offer a direct historical account. (Consider, though, that when Rawls’s book was published, many Americans believed that equality was settled law thanks to the 1964 Civil Rights Act’s prohibition of discrimination based on race, skin color, religion, sex, or nationality—even though the majority of activists’ claims had not been formally addressed. Maybe egalitarianism was in the air; some broad notion of justice certainly was.) Still, Rothfeld finds plenty of evidence that a warped, reductive version of egalitarianism animates many widespread arguments about beauty, art, and the so-called good life.

Take the decluttering fad initiated by Kondo, the minimalist influencer who pruned even her name for the sake of her brand. Her KonMari method asks us to test our possessions for their ability to “spark joy,” to keep the clothes and books and junk that do and toss the rest. In theory? Maybe not so absurd. But play it out: to base an object’s value on how readily it makes me smile would be to look at my glasses, my mug of coffee, and my early edition of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (illustrated by Picasso and purchased for eight dollars from a kind old woman operating out of a defunct velvet mill in rural Connecticut), and levy a flat, undiscerning endorphins tax on the three.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Rothfeld finds this particular modus operandi dubious and solipsistic. In the collection’s second essay, not so subtly titled “More Is More,” Rothfeld connects “tidying guru” Kondo’s fixation on books to the resurgence of fragment novels. Kondo orders her devotees to pare down their libraries to a single sticky collage of joy-sparking passages; compare that glue-sticked assemblage with recent efforts like Kate Zambreno’s Drifts (2020) and Jenny Offill’s Weather (2020), or even Patricia Lockwood’s No One Is Talking About This (2021)—which, for me, is “the best of the lot,” a distinction Rothfeld reserves for Jade Sharma’s Problems (2016)—and something unnerving emerges about their shared simplicity. Rothfeld quotes the late novelist and philosopher William H. Gass, who argues that that kind of simplicity is a “pioneer virtue,” a distinctly American, “defensive neatness that despairs of bringing the wild world to heel and settles instead on taming a few things by placing them in an elemental system where the rules say they shall stay.” Yet isn’t there a hint of tragedy in how fervently Kondo and the fragment novelists deprive themselves of extravagance, even mess?

The point may be moot; absolute tidiness is impossible. And critics love a good mess. On these points Rothfeld remains, understandably, quite raw. Her sixth essay, “Wherever You Go, You Could Leave,” recalls her suicide attempt as a freshman at Dartmouth. Recovery, her then-therapist said, would require learning how to suppress her natural impulse to judge things, instead allowing objects to flow in and out of her consciousness by “‘practic[ing] mindfulness,’ as if it were piano or a dance routine.” Effectively, the therapist suggested giving up criticism; again unsurprisingly, this supposed mind hack proved a nonstarter. Fortunately, the undergraduate soon found comfort in running and going to the movies. While cinema is the main subject of other essays—like the Cronenberg appraisal, “The Flesh, It Makes You Crazy,” as well as an astute assessment of the critic and filmmaker Éric Rohmer titled “Two Lives, Simultaneous and Perfect”—its passing mention in this particular context suggests the potentially existential stakes of aesthetic judgment.

¤

There are moral stakes to minimalist attitudes too. In “Normal Novels,” Rothfeld argues that Sally Rooney is so hemmed into her signature, hazily defined Marxism that her characters cannot bear thinking of love as anything other than a protest to capitalism—despite themselves being creatures of significant privilege and success. Rothfeld argues that the couples in Conversations with Friends (2017) and Normal People (2018) permit each other no more freedom than the sadomasochist Christian Grey permits the young Anastasia Steele in E. L. James’s 50 Shades of Gray (2011) or the vampire Edward permits Bella in Stephenie Meyer’s Mormon escapist fantasy, Twilight (2005). Yet, Rothfeld observes, just as those works flatter the vanities of those who want to see their own myopias reflected in literature,

Rooney and her readers hope to bask in the self-congratulatory glow of their supposed egalitarianism without ceding any of their accolades—and without acknowledging the uncomfortable truth that, even if economic inequalities were eliminated, other hierarchies would persist.

For Rooney to extract her characters from capitalism only to slot them into Marxism is simply to trade one paradigm for another—that is, to have them remain unfree. Of more value than such a swap, Rothfeld argues, would be to recognize that our desires are ambiguous, and to consequently write characters struggling to make sense of what they want from politics and institutions, as well as the relationships and experiences that constitute the rest of their lives. At its core, Rothfeld’s aim is to strengthen both our aesthetic and moral faculties. Doing so, she suggests, requires a particular kind of intellectual freedom: a greater willingness to embrace tension and paradox rather than settle for the convenient comforts of ostensible clarity and certitude. After all, as we squirm beneath the weight of overlapping and unwieldy pressures, how can desire be anything but ambiguous?

The potential upshot of this appears at its most cogent in “Only Mercy: Sex After Consent,” a survey of the debate surrounding affirmative consent after #MeToo that shows the value and the risk of unpredictable social relations. By the time we reach the essay—the longest in the collection—Rothfeld has worked to shore up our tolerance for ambiguity in art (by, for example, attacking the predictability of serial killer hunt shows likes Hannibal [2013–15] and Mindhunter [2017–19]). Because, if we can acknowledge that at least one desirable quality of art is that it resists the projection of our beliefs, and so to experience art in earnest we must, to some extent, suspend them, then we might begin to see how ambiguity can play a similarly meaningful role elsewhere—including in the bedroom, with respect to what we do with our bodies.

In “Only Mercy,” Rothfeld describes an ideological spectrum in which women are saddled with an impossible responsibility: that of knowing their sexual desires completely, communicating them to their partners, and receiving fulfillment in kind. To the right of that spectrum sits the “new puritanism” advanced by columnists like Rethinking Sex: A Provocation (2022) author Christine Emba of the Post and The New Statesman’s Louise Perry, who wrote The Case Against the Sexual Revolution: A New Guide to Sex in the 21st Century (2022)—reactionary post-liberals for whom the missionary position will do just fine, thank you very much, so long as both heterosexual married persons involved keep Rawls’s veil on in bed. On the left lie the institution reformers like Srinivasan, the Oxford philosopher whose much-discussed book, The Right to Sex: Feminism in the Twenty-First Century (2021), argues that the sexual revolution’s failure to also redistribute wealth and power has inspired women’s degrading sexual preferences.

As Rothfeld illustrates, these views are weak—yet not in the same way. The new puritans’ “appalling incomprehension of what good sex is like” is far more troubling than Srinivasan’s difficulty taking her argument further to propose a positive account of sex (the bridge between structural racism and some possibly tasteful choking having been tricky enough to build on its own). And so rather than arbitrate between two similarly complex frameworks, Rothfeld turns to 20th-century thinkers who clearly knew what constituted good sex: cultural historian Johan Huizinga and philosophers Mikhail Bakhtin and Georges Bataille. Taken together, Rothfeld suggests, the three offer a different vocabulary—Huizinga’s “play,” Bakhtin’s “carnival,” Bataille’s “eroticism”—that shifts the conversation from what is permissible to what is possible. Bataille frames flesh as “the extravagance within us set up against the law of decency,” claiming that sex is most rewarding when its participants are free to ravage one another to the point of mutual transformation—when positions or customs that seek to restrict sexual freedom between consenting adults are rejected. Accordingly, Rothfeld wants to approach the bedroom as a carnival ground, a place where, for better and worse, expectations will always be thwarted.

Sexual politics may be the only domain in which Rothfeld’s thinking on aesthetics readily carries over to ethics. With respect to Kondo, Rothfeld claims that when we enter the “aesthetic mode […] we submit wholesale to the demands and dangers of the artwork, no matter how impractical or grueling these turn out to be.” The value of art, she then admits, is that it is “superbly needless, for which reason it is anathema to the tactics of capitalists and declutterers alike.” Naturally, some tension between this passion, necessary for life and aesthetic appreciation, and the dispassion necessary for analysis is inescapable. Still, following Kant (“who else!”), Rothfeld suggests that this is the only way to understand what is wrong—with a work of art, a hookup, society writ large—before offering the kind of critiques that lead to improvement.

¤

All Things Are Too Small is a book about wanting more—from literature, from culture, from politics, from the people and pleasures that color our day-to-day lives. It’s a hard collection to like only because it demands a great deal of the reader, including, contra Barth, a willingness to engage in exhaustive analysis and comprehension of one’s own psyche. Rothfeld doesn’t pretend that doing so will guarantee understanding of one’s behavior or the wider world; still, she advocates fiercely for a willingness to keep trying.

In the final essay, “Our True Entertainment Was Arguing,” Rothfeld chips away at the traditional, restrictive institution of marriage while praising her beloved Rush’s Mating and the film His Girl Friday (1940). Rush’s narrator, a disillusioned anthropologist, heads to the Kalahari Desert, where a famous scholar who she believes can help her find her way is rumored to be running an experimental egalitarian commune. The two become lovers. For a time, it feels like their bed and the commune are two instantiations of the same higher form of justice. Rush knows this won’t last, and while the affair may be engrossing, its temporariness is of a piece with the insatiable nature of our lust for the ultimately unattainable.

“I love a demystified thing inordinately,” Rush’s narrator says. Rothfeld does too, not because there’s nothing more to be discovered but because the act of demystification is an illusion that leads to even deeper engagement; to reach the end of one line of inquiry is to find the beginning of another. In other words, the unknowable, including what we cannot predict about our return to objects we think we know well, is something to be ecstatic about.

LARB Contributor

Kenneth Dillon is a writer from New York. His work has appeared in publications including The Baffler, The Drift, Publishers Weekly, Cleveland Review of Books, Public Books, and more. Follow him on X/Twitter @kenneth__dillon.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Damned Poetry: On Ben Lerner’s “The Hatred of Poetry"

Becca Rothfeld on Ben Lerner's "The Hatred of Poetry".

Vampire Socials

The distressingly human lives of vampires today

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!