Sugar Daddy of the Right

A biography of the founder of the John Birch Society argues that this discredited fringe group actually won the war of ideas.

By Paul MatzkoApril 6, 2022

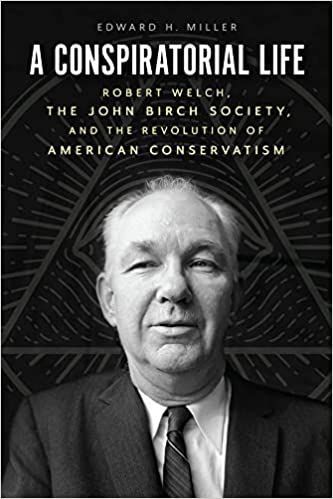

A Conspiratorial Life: Robert Welch, the John Birch Society, and the Revolution of American Conservatism by Edward H. Miller. University of Chicago Press. 464 pages.

IT IS TEMPTING to believe that we live in uniquely unhinged times, when it’s possible that the founder of a Japanese pornography website and his son can start a mass religiopolitical movement — QAnon — organized around the belief that global elites are trafficking children and drinking their blood. But historian Edward H. Miller’s new book, A Conspiratorial Life: Robert Welch, the John Birch Society, and the Revolution of American Conservatism, is a reminder that outlandish conspiracism has a long history on the right.

The mid-20th-century United States was a place where Robert W. Welch Jr., a bankrupted candy manufacturer and inventor of the Sugar Daddy lollipop, could found a national organization that would leave a conspiratorial imprint on modern conservatism — planting the seeds for today’s fever dreams.

The John Birch Society was named for an American missionary and intelligence officer who was murdered in China in 1945. For Welch, John Birch was the “first casualty of the Cold War,” a martyr whose life and death would inspire Americans to fight the spread of communism at home and abroad. And while Welch had rejected the Baptist religion of his youth, he would find Birch’s faith-based story useful when building support among white ethnic Catholics and evangelical Protestants.

In the early 1950s, Welch ran for lieutenant governor of Massachusetts, which he lost. He backed Senators Robert A. Taft and Joseph McCarthy, only to watch both be sidelined in national politics and die before the decade was out. Instead, the Republican Party nominated General Dwight D. Eisenhower, whom Welch believed did too little to repeal the New Deal at home while conceding too much to communists abroad.

Welch began traveling the country, giving policy-dense lectures to anybody who would listen, and started a newsletter that would become the American Opinion. In 1958, he founded the John Birch Society with the help of an assortment of Midwestern businessmen. Society membership peaked by 1966 at about 30,000, organized into chapters of no more than 24 members. Although small, the organization claimed influential conservative activists, including industrialist Fred C. Koch, antifeminist campaigner Phyllis Schlafly, broadcaster Clarence Manion, and Left Behind novelist Tim LaHaye.

Welch alienated many allies. He linked every item in the news to Kremlin-backed plots. Thus, it was the Eisenhower administration that had downed the U-2 spy plane in 1960 to provide pretext for a disarmament treaty with the Soviet Union; communist sympathizers in the Kennedy administration who had designed the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion to fail, to help Fidel Castro root out the opposition; and the communists who had carried out false-flag assassinations of Medgar Evers, Emmett Till, and Martin Luther King Jr.

Welch’s conspiracism was tolerated in right-wing circles until he accused President Eisenhower of being not just a useful idiot but a willing agent of the Soviets. That was a bridge too far, and conservatives like William F. Buckley Jr. distanced themselves from Welch, thus saving the New Right from the taint of conspiratorial extremism — or at least, that is what they told themselves; it has become part of the mythology surrounding Buckley’s National Review that it saved conservatism from the toy department.

Miller debunks this “ostracization thesis,” arguing that the idea that Welch was partitioned off from “a ‘responsible right’ was a delusion itself.” This is too strong. The break caused a short-term rupture among subscribers and donors for both the John Birch Society and the National Review. Buckley’s action had real negative consequences for Welch, but Miller is correct to note that the ostracization thesis was also an act of wish fulfillment.

The first generation of historians of the New Right, like George H. Nash, mostly omitted the likes of Welch from their accounts; but, as Miller argues, the John Birch Society is not a “story of rise, fall, and impotence” but “survival, growth, and significance.” Welch’s ideas might no longer have been welcomed in the pages of National Review after 1959, but his organization continued to grow numerically and financially, exerting influence on the far-right flank of conservative politics for a quarter of a century after his falling out with Buckley.

And Welch’s paranoid style persisted after his death in 1985. After the breakup of the Soviet Union seemingly left the society in want of a reason to exist, it shifted focus from a “vast Communist conspiracy” to something more familiar today: the suspicion that a shadowy group of “globalists” or “internationalists” were tugging the strings of billionaires and political elites with the ultimate goal of creating a world government.

Welch had tilled the soil for the rise of the post–Cold War paleoconservatives in the 1990s, those like Pat Buchanan who were fixated on combating a new world order. Buchanan’s blend of isolationism, populism, and protectionism would lay the groundwork for the 2016 election of Donald Trump. Buckley might have won the battle with Welch in the early 1960s, but Welch’s side had arguably won the war by the 2010s.

Miller invites the reader to compare Robert Welch with Donald Trump, which makes sense on a surface level: both were bankrupted businessmen who lacked paternal warmth in their childhoods and had a penchant for conspiracism. But Welch had intellectual pretensions, was a faithful husband to his wife, and was a true believer who poured every dollar he earned into the John Birch Society. None of these qualities are present in Trump.

The deeper lesson to be taken from Robert Welch’s paranoid passions is that conspiracism is not an ideology but a political style rooted in learned social distrust. Mid-20th-century conservatives distrusted the federal government, presidents, and political elites — and not entirely without cause. There was often a kernel of truth to even Welch’s most hyperbolic accusations. He was wrong, for example, that labor leader Walter Reuther threw the 1960 presidential election to John F. Kennedy so he could “be the boss of the United States under a one-world international socialist government.” But a few years later, conservatives felt vindicated when a copy of the “Reuther memorandum” was leaked, revealing that Walter Reuther and his brother, together with President Kennedy and his brother, had plotted to use the Internal Revenue Service and the Federal Communications Commission to censor conservative broadcasters.

Conspiracism flourishes in the space between the promises and failures of governing institutions. The best way to check paranoia is not to censor the paranoid but to reform the delinquent institutions that provide them with oxygen.

Edward H. Miller ends A Conspiratorial Life by warning that parts of the United States — filled with a cacophony of cable news pundits, talk radio hosts, and social media blowhards — have “become Welchland.” Indeed, Welch could only have dreamed of having the president’s ear, let alone of creating a conspiracy theory that would propel a mob through the doors and windows of the Capitol itself. The conspiratorial flank of the right is back and stronger than ever, albeit under the auspices of the My Pillow Guy instead of the inventor of the Sugar Daddy caramel pop.

¤

LARB Contributor

Paul Matzko is a research fellow at the Cato Institute and the author of The Radio Right: How a Band of Broadcasters Took on the Federal Government and Built the Modern Conservative Movement (Oxford University Press, 2020).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Ayn Rand, Live from Los Angeles

From a movie set extra to a famous Red Scare crusader in Los Angeles.

America’s “Mein Kampf”: Francis Parker Yockey and “Imperium”

A shadowy fascist, the late Francis P. Yockey (1917–1960) has followers today.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!