Sucker Punch

A response to Glen David Gold’s piece

about William Faulkner and Joan Williams.

By E.C. McCarthyDecember 11, 2011

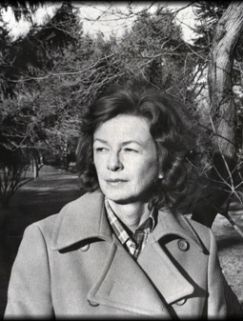

Photograph of Joan Williams, Courtesy Lisa C. Hickman

GLEN DAVID GOLD IS A HEARTBREAKER.

The first few paragraphs of this piece [On Not Rolling the Log] hooked me: writers and transactional relationships, written intelligently and quite beautifully. I wanted to learn something deeper of the nature of transaction, where it begins, how to manage it in the murky world of publishing and, pulling back, in the darker corners of life. I read on. I was disappointed.

Gold's piece is an abject lesson in sexism. Without reading a word of Joan Williams's National Book Award-nominated writing, Gold comfortably questions the authenticity of her book blurbs (not even her work, but her blurbs) from lauded male writers Robert Penn Warren and William Styron based on the fact that she had a five-year relationship with William Faulkner. Since she asked Faulkner for a blurb, Gold is emboldened to suggest she must have fucked Warren and Styron for their two cents, too.

Gold kicks the can down the road with seductive writing: a plausible script about poor Faulkner's right to be suspicious and temptress Williams's designs on famous male writers and their, er, blurbs. To read Gold's essay is to come away with the definite impression that Joan Williams was quite the bed-hopper and only a middling writer whose career was most famous for its failed transactions; never mind that she was a woman trying to publish fiction in the fifties, that she earned prizes and nominations and the endorsement of an impressive list of heavy hitters. "By all accounts, she was the real deal," Gold lamely offers; all accounts but his own.

I don't blame readers for loving Gold's essay. It is well-written fiction. Like a hot make-out session, Gold's machinations make the fantasy juicier. Joan Williams's "delta" is on full display, and then serves as a punch line delivered by her own fictional voice: "Can you imagine whatthat conversation needed to sound like? ... Williams: He still thinks fondly of my delta." Does it matter that Gold fabricates the extent of the affair, the feelings of Faulkner, from Faulkner's point of view no less, and picks a side in the "who's evil in this transaction" game he creates for our reading pleasure? Not if all we want is to read creative writing, but certainly if we expect to come away more knowledgeable about Faulkner, Williams, or literary transactions.

Let's address what is termed "transactional" in the story. With "a little knowledge of the internet" (Google and Wikipedia, presumably?), Gold decides that Williams and Faulkner had a steamy transactional affair, that Williams was a little too lucky in the blurb department, that she was one of those not really evil writers who asked her former paramour to support her work, and that her second marriage to her editor was "the ultimate transaction": this woman was a walking ding of the register till. However, Faulkner and Williams were no longer in a relationship when she requested his support, which means that Williams offered nothing for the blurb; she only hoped for an endorsement from a former mentor who should have validated her writing. Ironically, Faulkner is the transactional aggressor of the relationship: would he have denied her a blurb if she were fucking him? The Gold standard of appropriate exchange doesn't address this possibility.

Williams isn't alive and cannot respond to Gold's cynicism. Would Gold publicly question a living female writer in this way? I doubt it. A more instructive tangent for Gold might have been to explore (directly) how he himself would feel knowing that his work, his personal value, and his life decisions would be posthumously lumped together and judged by someone who hasn't read his books, yet posits that he must have slept with any famous female writer who praised his writing. I'd also be interested to hear Gold's thoughts on the creeping dread a writer experiences knowing there are people behind lecterns who speak without reading, and who promulgate conjecture as truth with a winking "Or are you a better man than I?" defense. Successful women encounter this type of questioning daily, both overt and implied, and it's regrettable that Gold didn't take the opportunity to dig deeper on the subject.

The final sucker punch of this piece is the reprise of Gold in the classroom, the reminder that he directed this insipid chauvinist logic at students; that he was teaching it. For me, that was the heartbreak moment. The knowing that if even one of his students isn't a critical thinker, his or her subconscious sexism may strengthen under the instruction of an articulate speaker like Gold. It perpetuates a destructive habit of devaluing women that generations continue to passively (or, in this case, actively) bequeath.

As for Gold's student and his "don't fuck Faulkner" tweet, I am optimistically inclined to read it differently than Gold. While Gold delights in what he sees as evidence that his tutorial has landed, I prefer to think that Jordan Abel was being sarcastic, that he sat through Gold's lecture and determined that none of it was worth a damn. Could an MFA student, most likely born in the eighties, hear Gold's questioning of Williams's career and not pick up on the sexism?

If, however, Abel's response was a lucid joke, I would caution him against reveling in judgment of Williams. A five-year affair isn't fucking, as any grown-up will tell you, and long-term relationships between artists are predicated on the alchemy of comparable talent and sensibility, as any great writer knows. Faulkner evidently mourned the loss of Williams long after their association ended, and to follow Gold's narrative of this "transactional" affair is to miss the soul of their story completely.

Transactions are not evil by nature; most everything in life is accomplished through conditional exchange. The Review's publishing of Gold's essay is a form of trade, as is the printing of my response. When people marry they often give each other rings — a symbolically equal transaction. But many aspects of give and take are unspoken and expectations are not always fully understood by the participants, at the time, after the fact, or ever. Gold's lopsided analysis of Faulkner and Williams's love affair is an opportunity to examine closely the inimical nature of judgment, not transaction, and for that I am grateful. I am now off to read Joan Williams, a writer who I expect will rival her more famous male contemporaries, and the generation before her, many of whom clearly loved her writing. If anything redemptive comes of the Gold transactional literary clusterfuck, it's that Joan Williams will be more widely read.

LARB Contributor

E.C. McCarthy is Deputy Editor at the Los Angeles Review of Books. She lives in Los Angeles.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Not Pretty: On Edith Wharton and Jonathan Franzen

Do we even have to say that physical beauty is beside the point when discussing the work of a major author?

Transactions Along the Mississippi Delta

On literary sociality and the romance between William Faulkner and Joan Williams.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!