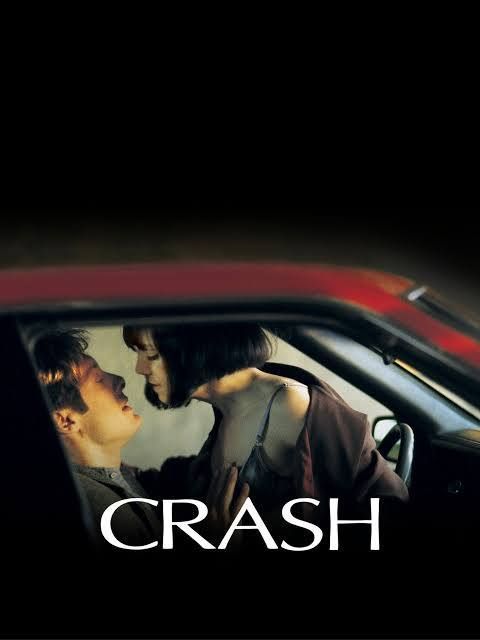

Still Raw: Love in David Cronenberg’s “Crash”

Hattie Lindert argues for David Cronenberg’s “Crash” as the ideal Valentine’s Day movie.

By Hattie LindertFebruary 14, 2024

IN THE FINAL 30 minutes of David Cronenberg’s 1996 film Crash, the car-crash fetishist Vaughan (Elias Koteas) is getting a tattoo—gun-black ellipses along the pale and mottled scar that crawls up his rib cage and mirrors a sedan grill. He objects to the white-coated woman’s handiwork; he calls it “too clean.” “This is a prophetic tattoo,” he insists, and “prophecies are ragged and dirty.” Reclining shirtless in an infirmary, dictating how the buzzing needle should pierce his skin, Vaughan literally and figuratively creates himself. Later, and after prolonged sexual tension, he and the commercial producer James Ballard (James Spader), who shares his kink for car crashes, finally caress one another in the backseat of Vaughan’s battered Lincoln Continental, gasping and sucking and stroking. Ink still raw and raised, they prod like fascinated strangers. Nobody climaxes. It’s the film’s most passionate kiss.

This tender lens on gruesome transformation drives Cronenberg’s most controversial film—and confirms it as his most romantic. Vaughan, a voyeur who spends his days photographing corpses impaled by dashboard ornaments and prostitutes with their hair splayed across center consoles, leads a collective of disenfranchised car-crash survivors who now seek erotic thrills that reinvoke the bloody minutiae of their collisions. Those who do have jobs or families are indifferent towards them—the real game is elsewhere. There are no grand affairs here between leading lads and ladies; in their place are the famous fatalities (James Dean, Jayne Mansfield) that Vaughan restages for a rapt audience in an abandoned lot, or the parking-garage trysts. The dogged pursuit of what Vaughan will later call a “fertilizing accident” replaces weepy airport reunions or embraces in the rain. That initial swooning moment, however violent and consequential, becomes a new form of being wrought from the cold hard chassis and vinyl interior, the direct consequence of chasing authentic personhood.

Based on the 1973 novel of the same name by J. G. Ballard, Cronenberg’s Crash follows a man and his wife, Catherine (Deborah Kara Unger), as they fall in with Vaughan’s crew following a genuinely coincidental head-on collision. Early in the book, the protagonist—he shares a name with the author—marvels at a dead body in the crushed hull of a totaled vehicle: “The intimate time and space of a single human being had been fossilized for ever in this web of chromium knives and frosted glass,” he observes.

Some two decades later, Cronenberg’s mostly faithful adaptation sharply divided the audience at its Cannes screening. It was decried as smut by countless detractors; award jury chair Francis Ford Coppola was so put off by the film that he refused to personally present Cronenberg with the Special Jury Prize it had been awarded. Fine Line Features head Ted Turner lamented that he has been unable to halt release of the film in the United States: “I guess they took the hatchet out of my hands,” he said. Still, it received only a scattered and delayed American distribution, largely due to its NC-17 rating, and was unreleasable elsewhere, outright banned in Ireland over a scene in which Catherine fantasizes about Ballard having sex with Vaughan. Cronenberg himself has called Crash “an existential romance.”

Unlike most love stories, however, Crash’s conception of intimacy blossoms outside of any person-to-person union. Characters engage primarily in sex that could politely be called “nonreproductive,” more often than not finding vaginal intercourse unsuitable for any honest attempt at climax. Fucking and gripping the clutch of an automatic transmission are mechanical thrills of equal measure—and equally easy to nudge into the banal. Catherine’s dirty talk, as Jessica Kiang notes in a 2020 Criterion essay on the film, strings together whispered “noneuphemistic, anatomical language [such as] penis, anus, semen,” rather than sultry, personal nothings. Even the score’s dissonant guitar strains, which pick and tear at one another as they soundtrack the divider-locked gray pavement that sets most scenes, never exactly harmonize.

But in Crash, arousal is alive—ragged, uncontrollable, a desperate and unabashed pursuit. In an early scene, members of Vaughn’s cult sit huddled around a TV set as it plays a tape of crash-test dummies being bisected by brick walls or midsize sedans. They bite their lips; they gasp; they touch themselves; they touch one another. Orgasm is by no means a quick fix for these knotty and proudly fractured humans, but fumbling for its sticky release provides the kind of new terrain that seems essential to inner and outer healing.

Plenty of comfortable parallels to the disenfranchisement of 21st-century social life wander among Cronenberg’s hollowed-out dealerships and sharp-edged salvage yards. We date online and fuck on apps and go to therapy on Zoom. Loneliness is a global health issue, and porn-brained kids don’t even want to see real lovers on TV anymore. The choking and unchoking traffic—as Ballard and another auto-adorer, Dr. Helen Remington (Holly Hunter), remark, drawn together after their first shared collision—moves like a shuffling mass. It’s not hard to understand the protagonist’s feeling of removal, hands on the balustrade of his hotel room balcony while the bones in his thigh bond back together, watching drivers bob and weave as he stands like “a potted plant.”

But trying to firmly tack a message as clean and visceral as Cronenberg’s onto the corkboard of analyses of “modern society” sort of misses the point. For every new alleged teen sex craze fretted over by morning show news anchors, there’s some shiny new AI arm of the surveillance state to be terrified of as well. Cronenberg himself rejects framings of Crash as some fable about sexual danger, instead urging audiences to engage with the tone of each dalliance, noting when participants finish and when they don’t. He told Film Comment in 1997: “It’s sort of initiation into an awareness and a slant on life. At the beginning of the film the sex is rather anodyne, it’s lost its power. It only regains some of its power when it’s connected to other forces that give it meaning and life and dynamism. It’s sex against death.” He recalled a viewer at an early test screening of the film who complained that a series of sex scenes couldn’t constitute a plot. Why not, he wondered, if they were the right sex scenes? Why couldn’t an entire life be reflected in a series of physical collisions that leaves one, however subtly, not the same?

Gruesome remodeling of one’s own earthly vehicle appears often across Cronenberg’s catalog: the second uterus feeding off rage in The Brood (1979), the goo and flaking skin of Jeff Goldblum’s Seth Brundle in The Fly (1986), and, most recently, the filleted orgies of Crimes of the Future (2022). Body horror is an interrogation of form by nature. Crash marks an important transition for Cronenberg towards looser interpretations of what it means to change into something, or someone, else. In 2005’s A History of Violence, the scene that most clearly communicates family man Tom Stall’s backsliding into the sadistic mentality of his criminal past is a close-up shot of actor Viggo Mortenson’s hardening stare of indifference.

In Crash, guilt, shame, and regret are less than afterthoughts. These people don’t pause to contemplate their reflections in any of the glinting chrome fenders, helicopter noses, or hazy pools of semen that dot the film and the book. From the moment that Helen Remington tugs at her seatbelt to bare her friction-burned breast in her first encounter with Ballard—a crash that ejects her husband through both windshields, killing him—the remaking of the self is automatic and unforgiving. Living your ugly truth is the porn of choice for Remington and Co., a “fertilizing accident” striking that match—the point of no return that forms a gateway to a world of new embodied experiences and uniquely sensitive skin. When Ballard’s lips brush the healed gash that runs up the thigh of Gabrielle (Rosanna Arquette), a Vaughan associate who was left in a full-body brace by her crash, they both cry out—it’s as if he finds the pilot light for arousal not in spite of her scar tissue but because of it. In this way, the film’s most transgressive scene also becomes its most regenerative.

This was not the first time Cronenberg laid plain the concept of a different body as a new lease on existence. The “new flesh” of his 1983 opus Videodrome gets evoked throughout Crash. But in that earlier film, James Woods’s Max Renn must kill himself to be born anew, compelled by a cooing, scarlet-haired Debbie Harry. What the next life looks like for Max isn’t spelled out, but it’s unambiguous that full metamorphosis doesn’t happen without death. The allure of his new body is also largely how handy it is for taking down the shadowy forces that changed him in the first place.

Crash is different. Blood and semen and engine oil and slobber and tears converge into a viscous fountain of something like youth. Death, though attractive, is less liberating than deformation—the twisting and bruising of one body is the only way to uncover the silhouette of the next, when a brace becomes as alluring as a fishnet stocking. Battered people fuse and uncouple, tearing open new divots of opportunity. Car crashes, like any accidents, result from horrific chance: how human of Vaughan, then, to dedicate his life to orchestrating and recreating these momentous impacts, forcing an index onto chaos? Love and devotion are not the same, but don’t we seek them out for similar reasons, as wellsprings of overarching explanations?

Perhaps leaning into literal auto-erotica is some sort of perverse surrender to the modern world. But Crash presents us with people who find an endless source of meaning in their lives by brutally colliding into new shapes, new affairs, and new bodies, as a means to wrench themselves free from a familiar metal shell. All the pain and pleasure doesn’t seem so inhumane then—in fact, carving out an unapologetic personhood, through labored ecstasy and disaster and a near-sacrificial conviction, may be the ultimate act of self-love. As Karina Longworth says of Crash in an episode of her podcast You Must Remember This: “These are people who are going to keep pursuing their fetish until they die. And in working together towards their mutual death, they’ve reinvigorated both their lives and their love.”

I don’t have a lover, but I do have a car. It’s a 2011 Subaru Forester, blue like a lake under ice, bought used with a dirtied gray leather steering wheel that leaves my bare hands smelling of oil and sterilized animal if I grip too hard. I’ve owned other cars and totaled two, but this one feels most wed to me, a pseudo–other half pocked with as many small disfigurations from past breathless joyrides as I am. We’re a unit, vested in love and isolated necessity, skulking the barren backroads of my hometown with the rotted muffler screaming, basking in oncoming headlights and traffic signals and the faint glow of the television sets through curtainless cottage windows. When I’m driving, everyone else is no more than a pedestrian or a passerby. I’m on the road.

LARB Contributor

Hattie Lindert is a writer based in New York whose work has appeared in Pitchfork, The A.V. Club, and The Face. She was born and raised in Vermont.

LARB Staff Recommendations

David Cronenberg Wants to Be Inside You: On “Cronenberg: Evolution”

On November 1, 2013, the Toronto International Film Festival opened its first original traveling exhibition entitled Cronenberg: Evolution.

It's Dangerous to Be An Artist: An Interview with David Cronenberg

A lot of filmmaking in America is nostalgia filmmaking, trying to recapture what you loved as a kid. I'm not a nostalgia freak.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!