Staring into a Total Eclipse: On Adam Hochschild’s “American Midnight”

Robert Slayton examines Adam Hochschild’s “American Midnight.”

By Robert SlaytonMarch 16, 2023

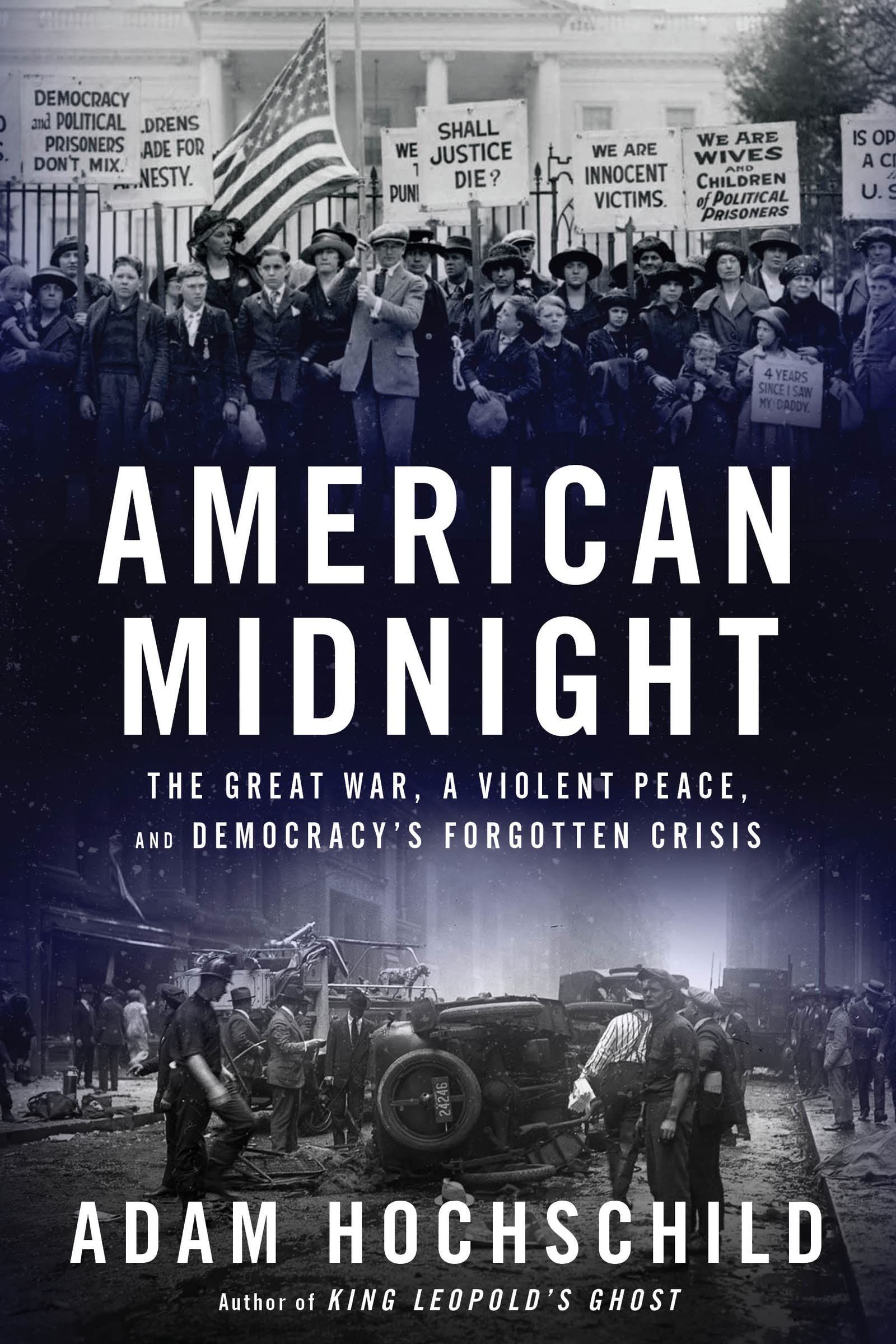

American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis by Adam Hochschild. Mariner Books. 432 pages.

WITH A NOD to January 6, 2021, Adam Hochschild’s new interwar history, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis, tells the tale of “the extreme repression of 1917 to 1921,” a time when the United States subverted its democracy and gave in to hysteria.

Driven by war fever, Americans turned on anyone and anything they cast as traitors and dangers: immigrants in general and Jews in particular, labor in general and Wobblies and Socialists in particular, and, of course, African Americans. General Leonard Wood, who expected to become president in 1920, bellowed his plan to “deport these so-called Americans who preach treason openly.” An Iowa senator promoted “a one-language nation.” Even in New York—a place Hochschild describes as “the most multilingual city on earth”—an alderman sought to ban any “meetings held in alien tongues.”

This hysteria was fueled by several forces. Woodrow Wilson had run for reelection on a campaign to keep the country “out of war.” When, months later, he reversed course and declared hostilities, the administration was worried that the response might not be wholehearted. Among other things, they assigned George Creel—one of history’s great propagandists, although Hochschild barely mentions him—to pump up jingoism. The Bureau of Investigation and the American Protective League suppressed dissent. The threats were mainly imaginary, but enough socialists were imprisoned that, “had they all been in one place, they would have been able to hold a party congress behind bars.”

After seeing the Socialist Party destroyed, with any money spent on appeals for others as well as for herself, Emma Goldman wrote, “We had nothing left, neither literature, money, nor even a home. The war tornado had swept the field clean.” At one time, her private secretary had been an undercover agent; a fundraising dinner was covered by spies from no fewer than three government agencies. All the leaders were jailed, including presidential candidate Eugene Debs. All their printed materials—newspapers, magazines, flyers—were banned from the mails by a vengeful postmaster general. It would never regain its prewar stature in the United States.

Hochschild brings talents to this endeavor. His prose is sparkling and accessible, free from academic jargon. In particular, he has a good ear for the pungent quote, examples of which are sprinkled throughout the book. Responding to critics of the war, the Nashville Banner bluntly endorsed the hostilities: “Let ’em shoot! It makes good business for us!” A critic of Ellis Island branded it “Dante’s Inferno […] a seething, struggling, volcanic mass of breathing human beings. Gentlemen, it is dangerous! Bolshevists and anarchists are made there overnight.”

We also get a window into absurd rhetoric that foreshadows today’s discourse. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, seeking presidential nomination, pitched his strengths: “I am myself an American, and I love to preach my doctrine before undiluted one hundred percent Americans, because my platform is, in a word, undiluted Americanism.” Heywood Broun rejoined, “We assumed […] that his opponents for the nomination were Rumanians, Greeks and Icelanders.” Checking out Palmer’s rival’s headquarters, he was “astounded to discover that he, too, is an American.”

Wilson was the epitome of preacher-as-president, his dour countenance projecting his holier-than-thou personality. Yet the morning after his honeymoon night, a Secret Service agent caught him dancing a jig while singing “Oh, You Beautiful Doll.” From the other end of the social scale is this anecdote about Emma Goldman in prison: “Her gift for befriending people was repaid when a group of Black women prisoners sewed her daily quota of 54 jackets to give her a day off for her birthday.”

Some of these stories of American paranoia are horrific. In Georgia, a lynch mob killed 13 Black people, among others a farmworker, whose courageous wife, eight months pregnant, made what a local paper called “unwise remarks” in protest. Hochschild described the response:

The mob strung her up to a tree by her ankles, doused her with gasoline, and set her on fire. As she screamed in pain, a member of the mob knifed open her belly, and when her unborn child fell to the ground and gave a cry, men stomped it to death […] The mob included the foreman of the county’s grand jury. No one was ever prosecuted.

Hochschild is not an academic historian, and his text includes some inaccuracies, as well as failures to fully flesh out an argument. He notices, for example, how W. E. B. Du Bois, previously a critic, changed gears and suddenly supported the war. Hochschild chalks this up to his belief that patriotism would benefit the race. But David Levering Lewis’s masterful biography of Du Bois revealed that army intelligence, through a third party, promised prosecution if he didn’t change his tune.

Hochschild also assigns early opposition to entering the war—especially on the side of the Allies—exclusively to the Socialists. That leaves out important groups: citizens of German descent but also the massive numbers of Irish Americans who hated Britain for its repression in their homeland, as well as immigrants from other parts of the British Empire, such as India or Egypt. Similarly, he notes how Wilson is mobbed by jubilant crowds on his way to Versailles but fails to mention the main reason: the war had exposed a network of secret treaties, unknown and undebated, that forced nations into the bloodbath that was World War I. The United States, alone, was never a part of this, and entered the conference with clean hands.

Hochschild’s subtheme is that this era of a century ago is a warning, a reminder of the fragility of democracy. Politicians branded the Great Migration of Black people to northern cities as a plot to import voters, just as Republicans claim now about immigrants. One senator amalgamated many fears into one amazing statement, affirming that “aliens were being smuggled across the Mexican border at the rate of 100 a day, a large part of them being Russian Reds who had reached Mexico in Japanese vessels.” The Post Office’s legal counsel proclaimed: “I am after three things and only three things—pro-Germanism, pacifism, and ‘high-browism,’” the last an echo of our era’s anti-intellectualism. And on Memorial Day in 1927, around 1,000 Klansman marched through Queens and fought with local New Yorkers. Many were arrested, among them a real-estate developer named Fred Trump, father of Donald. Left unexplained by contemporary press accounts was whose side he was taking.

Hochschild’s conclusion is a portent of what we must fear and guard against. “[E]very generation or two we learn anew just how fragile [our democracy] can be,” he writes. “Almost all the tensions that roiled the country during and after the First World War still linger today.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Robert Slayton is professor emeritus in history at Chapman University. Slayton is the author of eight books. His book Beauty in the City: The Ashcan School (SUNY Press, 2017) won the Gold Medal for US Northeast–Best Regional Non-Fiction in the 2018 Independent Publisher Book Awards (IPPY) and Silver for Nonfiction History in the 2017 Foreword INDIES Book of the Year Awards. Empire Statesman (2001), his biography of Alfred E. Smith, 1928 presidential candidate and the first Roman Catholic to run for the nation’s highest office, was endorsed by Pulitzer Prize winner Robert Caro, who called it “vivid and insightful,” while Hasia Diner, holder of the Steinberg Chair at New York University, referred to it as an “exemplary biographical narrative.” It has been reviewed in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Yorker; Wikipedia cites Empire Statesman as the standard biographical work on Smith. His book Back of the Yards: The Making of a Local Democracy (University of Chicago Press, 1986) was chosen by Choice, the library journal, as one of its “Outstanding Books,” while New Homeless and Old: Community and the Skid Row Hotel (Temple University Press, 1990) was awarded Honorable Mention for the Paul Davidoff Award by the Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning. His articles have appeared in Commentary, New Mobility, and Salon, and in newspapers including The New York Times, The Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, Chicago Sun-Times, Los Angeles Times, and The Orange County Register.

LARB Staff Recommendations

No Home at All?: On Kenneth B. Moss’s “An Unchosen People”

David N. Myers reviews Kenneth B. Moss’s “An Unchosen People: Jewish Political Reckoning in Interwar Poland.”

“The Leprosy of the Soul in Our Time”: On the European Origins of the “Great Replacement” Theory

Richard Wolin excavates the roots of the right-wing conspiracy theory that liberal elites are trying to “replace” white Americans with nonwhites.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!