In the 21st century, we are inundated with news about human-induced climate change. But perhaps human-produced media are not the only source of information. What if the best source of news about the planetary effects of environmental damage was the planet itself? This essay is one of a four-part series, Speaking Substances, that considers the stories that might be told by unusual, sometimes nonhuman, but still-eloquent media: Ice, Oil, Bodies, and Rock.

THIS SERIES, Speaking Substances, has so far considered three different substances — Ice, Oil, and Bodies — to explore what we learn from seeing planetary objects as media. This focus is in keeping with a recent development in the humanities often called the nonhuman turn. The goal of the nonhuman turn is to diminish the centrality of the human in critical thought: to pay better attention to the material world, and to abandon the anthropocentric position that has caused so much damage to that world.

There is a great deal of pleasure in this body of work — the pleasure of opening the body to the vibrancy of the material world — but also a sense of urgency, registered in its frequent invocation under the sign of the Anthropocene. By learning to receive the messages transmitted by planetary media, then, we might begin to grasp what humans have done to create the present planetary crisis, and to uncover some hints about things we might do differently.

I confess to some ambivalence about the nonhuman turn in this respect. After all, not all humans turned away from the material world in the first place. As Zoe Todd points out, the nonhuman turn too often celebrates itself “for ‘discovering’ what many an Indigenous thinker around the world could have told you for millennia. The climate is sentient!” And nonhuman media have been used by some humans to try to take possession of others, as Kyla Schuller’s essay in this series makes clear. In this light, I think, the critical turn to the nonhuman, if it wants to stop being, as Todd notes, another mode of colonization, needs to give sustained attention to ongoing histories of dehumanization that condense around nonhuman/(some) human relations. Rather than simply decentering the human, we might ask whether that critical move can be used to interrupt those ongoing histories.

Originally conceived around rock — the oldest planetary medium — this essay went on something of a wild ride in the process of composition, thanks to its collision with two other objects that demanded to be treated as media: plastic, in the form of the plastic stones whose discovery was first announced in 2014, and then — via the comedian George Carlin’s riff on plastic — to the asshole, and queer theory. In looking at these three media — rock, plastic, assholes — I want to ask about the relationship between inhuman abuses and posthuman pleasures, and whether the latter can be deployed in a manner that might, perhaps, slow the former.

The Rock Record

Geology, a science often appealed to by posthumanist thinkers, implicitly recognized the existence of non-human media when, some two hundred years ago, they began to speak of the information conveyed in the “rock record” — the planet’s most ancient archive. As new materialist media theorist Jussi Parikka observes (in a book that partly inspired this forum) catchphrases like “the rock record,” “the annals of nature,” or more colloquially, the “stone book of nature,” all identified lithic matter as a data-storage medium, suspending information which, properly received and decoded, narrated the long history of the earth.

To think about rocks and other planetary matter as media, then, is also to see them as agential; they are not inert matter but lively forces, communicating with us across deep time. It isn’t clear whether the rocks actually see us as interlocutors; to them, we may seem inconsequential. Yet it’s increasingly clear that we need to listen to them better than we now do. This, in short, is the lesson of the Anthropocene proposal, which, if adopted, would encompass humanity as part of the “rock record,” reading a history of demonstrable, and potentially disastrous, anthropogenic impact on planetary systems through the legible geologic traces humans have left behind.

As those who have followed the debate will know, the designation of the “Anthropocene” is not without controversy. First, there is significant disagreement about when the Anthropocene will be said to have begun; and second, the name strikes many as not only inaccurate but counterproductive. Naming the whole species as cause of the current crisis, they argue, falsely universalizes the planetary impact it seeks to register, ignoring histories of economic exploitation and racial stratification, which can rarely be read in the rock record, but which give us a more accurate picture of how things came to be as they are. As Rob Nixon comments, “We may all be in the Anthropocene, but we are not all in it in the same way.”

From this perspective, we should instead find a more accurate name for the epoch, such as Jason Moore’s “Capitalocene,” or perhaps the “Colonialoscene,” or Nicolas Mirzoeff’s “white supremacy scene.”

Supporters of the term “Anthropocene” counter that its universalism brings into view the potential extinction of the human species as a result of climate catastrophe. We may not all have caused the present crisis equally, they argue, but if action isn’t taken, we will all suffer equally in the end. Yet whether a geological marker located somewhere in the (relatively recent) past can gesture, at the same time, to the speculative future of human extinction and the undeniable present of human exploitation remains to be seen.

The earliest readers of the rock record were inclined to use it either to erase, or actively to affirm, existing social and racial hierarchies. Stratigraphy, the method of receiving and interpreting lithic data developed by William Smith in the early 19th century, relies in part upon the way rocks store time in the form of fossils. The appearance and disappearance of plant and animal species across deep time helped geologists organize the history of the earth. (The Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras, for instance, are divided on the basis of a mass extinction event affecting an estimated 75 percent of then-extant species, including the dinosaurs.)

Yet fossils, as they transmute one form of time into another — organic ephemerality into mineral durability — may also haunt the living, testifying to the inevitability of their own species death. This is the paradox of new materialist media theory as far as the rock record goes. Thinking about rocks as media makes them less alien to us; it allows us to see them as lively — and yet the information encoded in the “rock record” is organized to a large degree by death and disappearance.

Nineteenth-century geological thinking reconciled the centrality of death to the legibility of lithic media by affirming that both planetary and social history worked according to the “laws of progress.” The perspective from which geologists read the rock record positioned it quite literally as foundation for the largely Euro/American followers’ claim to civilized superiority, and pragmatically as part of the practice of land grabbing.

Geologists casually folded racial hierarchies into the rock record. In the 1840s, as recorded in his A Second Visit to the United States, Charles Lyell went to investigate the site of the New Madrid earthquakes of 1811–1812. Part of the data he recorded about the region included the “tradition of a great earthquake,” occurring prior to 1811, maintained by indigenous tribes of the Mississippi Valley. But Lyell took the landscape as a more reliable witness than the lived memories of Native Americans: he argued that this must have taken place many centuries earlier, because the area lacked the sink holes which, he contended, such an earthquake would have left behind. Folding Native Americans and their knowledges into geological substrata, Lyell’s geology in effect materialized the contemporaneous myth of the “Vanishing American,” which also sought to eject indigenous people from the American present tense. As Kyla Schuller also shows, geology, despite its ostensible concern with non- (or post-) biological matter, has always been intimately involved in settler-colonial biopolitics. Lyell’s offhand correlation of Native tradition with the rock record points us to an important aspect of that intimate involvement: even when the times they seek to describe are pre-human, encounters with the rock record are not pre- (or post-) racial.

One recent proposal for an Anthropocene boundary marker challenges the violence of settler-colonial stratification by linking it to catastrophe rather than civilization. The Orbis hypothesis, proposed by Simon Lewis and Mark Maslin, names the year 1610 as the epoch’s starting date. They base this dating on a dip in carbon dioxide levels in Arctic ice cores, which they tie to the deaths of more than 60 million indigenous Americans in the century following European contact, marked by means of the resultant reforestation of the Americas and decline in human carbon-producing activity there. The Orbis hypothesis recognizes anthropogenic damage to the human as well as the nonhuman world as co-constitutive. It’s not likely that this proposal will be endorsed by the Anthropocene Working Group; a majority of that group views Lewis and Maslin’s interpretation of carbon data as historically evocative but geologically questionable. This underscores the partiality, the insufficiency of strictly geological readings of the rock record.

It’s hard, as I’ve observed elsewhere, to imagine what geological markers might register the simultaneous emergence of chattel slavery in this period. Or, for that matter, to locate testimony about how settler colonialism remains active on the surface of the planet, not only marked in its strata. This was all too painfully demonstrated by the murder, earlier this month, of Berta Cáceres, a Lenca environmental and land rights activist in Honduras. Cáceres was one of hundreds of environmental activists, a large percentage of them indigenous, murdered worldwide over the last few years — many of whom fought against the theft of their lands for hydroelectric dams and other green capitalist projects. The Anthropocene concept can only hope to recognize the accumulation of what Rob Nixon calls “slow violence” by destratifying the reading of lithic media, not so much marking time in discrete layers and localized boundary markers as emphasizing its ongoing, processual character.

Plastic

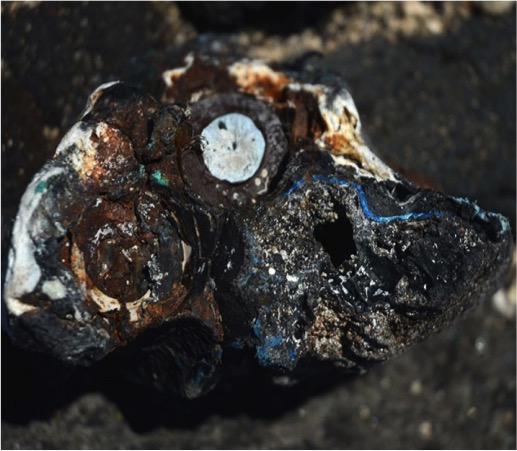

The “rock record” is itself a process, not an object, continually mutating and demanding to be read in multiple ways. In 2014, geologists Patricia Corcoran and Charles Moore identified a new form of rock made of plastic, dubbed plastiglomerate.

A plastiglomerate is “an indurated, multi-composite material made hard by agglutination of rock and molten plastic.” In layperson’s terms, plastiglomerates are lithified trash: eroded shreds of plastic fused with naturally occurring minerals into a new durable material. Plastic rocks speak to Parikka’s alternative name for the new epoch, the Anthrobscene. The word “obscene” might have descending, etymologically, from the Latin for “heap onto filth,” which, Kathleen Dean Moore declares, makes it a better name for the present both geologically and ethically. And indeed, the beach where the rocks were located, Kamilo Beach, located in the southeast corner of the island of Hawaii, is a vivid illustration of this kind of obscenity.

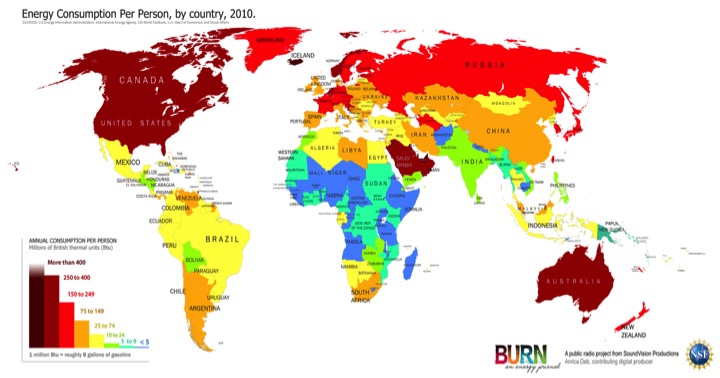

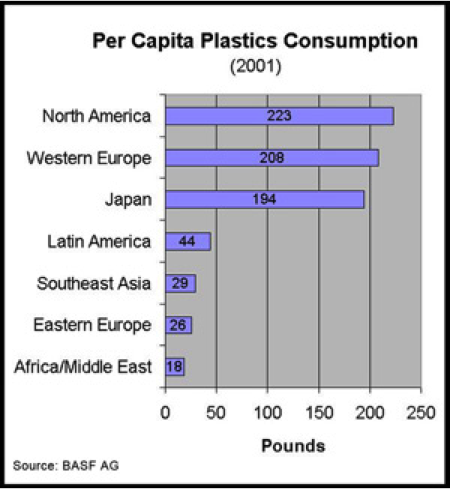

Kamilo Beach’s location makes it a dumping ground for tons of debris from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch — a swirling gyre of plastic (the consumption of which is, like that of fossil fuels, significantly unbalanced globally). From the perspective of the Anthrobscene — a view of environmental history as an ongoing garbage pile — the trash that washes up on Kamilo Beach is another wave of the destruction that began with James Cook’s landing in 1788.

It may have been something of a disappointment to realize, as Corcoran belatedly did, that the plastic-rock specimens Moore first thought to have been forged by volcanic lava were actually created by fires set by humans, either carelessly, in the form of bonfires lit by tourists and campers, or deliberately, in an attempt to clear some of the trash on the beach by burning it. The latter is the only explanation that makes sense, since that area of the island has not experienced active lava flows for over a hundred years, long before the invention of plastic. But the notion of volcanic transformation offers a seductive image of cosmic recycling: the earth remixing something born of human invention, though outside human intention — of fixing, in Gaian style, what humans can’t manage to get right. (It isn’t clear what the planet plans to do about the economic inequality that generates overconsumption, but that’s always been one of the weak spots in the Gaia hypothesis.)

Comedian George Carlin, back in 1992, proposed a grimly funny Gaian vision of the planet’s incorporation of plastic. Disparaging the environmentalism practiced by “white bourgeois liberals” who claim to want to save the earth, but are mainly interested in prettying up their own backyards, Carlin imagines the planet’s counter-perspective: maybe plastic is something it wants, and humans merely a means to an end:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8r-e2NDSTuE

Its recent embrace by climate change deniers notwithstanding, Carlin’s cheerful riff on human extinction affirms the evidence we now have about global warming. “The planet is fine,” he asserts, but “the people are fucked.” The addition of plastic to the rock record might be saying something similar — our garbage (in its myriad forms) may end up burying us.

Assholes

From the perspective of geological time, the most salient fact about humans is not sentience, but mortality. This explains why the Earth, in Carlin’s routine, having gotten humans to invent plastic, would proceed to dismiss them as assholes. It’s not just that humans appear, in this riff, only as producers of waste. Rather, as his assertion that the species is “already on [its] way out” indicates, we are set apart from rocks and plastic — which the earth intends to keep — by the relative ephemerality of our flesh. The asshole signals not a hole in time but a punctuation mark: an ending, or a reminder thereof. Not everything that dies has an asshole, certainly; but everything that has an asshole dies.

This is a biological fact, of no inherent social significance. But as queer theorist Leo Bersani points out in his renowned 1987 essay, “Is the Rectum a Grave?,” the association of the asshole with morbidity has taken on a profound psychological significance for some humans. Bersani’s essay, written in the first decade of the AIDS pandemic and in response to the virulent homophobia that characterized this moment, is complex, but the question posed in its title brings its argument into focus. The rectum is a grave, he argues, symbolically and psychologically, for “the [Western] masculine ideal … of proud subjectivity.” That ideal, predicated on a view of the human subject as a bounded, self-possessed entity, controlled by a rational mind, maintains a deep anxiety about anal penetration, which seems to refute that boundedness. The asshole, from this perspective, becomes the dividing point between the capacity for self-possession and a kind of self-annihilation.

The bounded self that Bersani describes (and deplores; the idealized self, he asserts, becomes “a license for violence”) has also come under fire, of late, from new materialists and ecocritics, who point to the modern, Western fantasy that humans exist unto themselves, apart from nature and in control of nature (and of other humans) as intimately involved in the generation of the current crisis. Like Bersani, they see the dissolution of this model of the self, this mode of being human, as a necessity if humanity is ultimately to survive.

Here is where Bersani’s tale of death and the asshole at once diverges from and coincides with Carlin’s. They operate on different levels, of course — Bersani’s is a figurative death, the death of a form — the bounded subject — as opposed to the biological death, the removal of a species — homo sapiens — imagined in Carlin’s cheerfully extinctionist fantasy. But more than that, Bersani’s “nonsuicidal” mode of self-annihilation suggests itself as a possible antidote to the self-trashing species identified by Carlin. The pleasure of embracing the rectum-as-grave, of dissolving the fantasy of the bounded, sovereign self, becomes, for Bersani, a point of departure leading to other ways of being in the world.

And while Bersani acknowledges that these pleasures do not substitute for the immediacy of struggles for reform, they do, he insists, “propose what are for the moment necessarily mythic reconfigurations of identity and of sociality,” imaginings that are nevertheless a needed and vital political activity. In this sense, the asshole could also be an opening — to an ethos that might possibly avert the fate Carlin predicts.

Postscript: Noise

Bersani’s affirmation of the rectum-as-grave amplifies and remixes the noise transmitted across all the nonhuman or nontechnological media I have discussed (rocks, plastic, assholes): the noise, that is, of death. The lithification of plastic enables humans to catch a speculative glimpse of themselves in the mineralized morbidity used to read the “rock record.” A response posited under the sign of the asshole launches morphological penetrability toward the death of a form (the self-possessed human) in an effort to prevent its demise in fact. This response reproduces some of the problems with the Anthropocene concept noted above: attempting to reimagine sociality apart from economic questions, and potentially disseminating a false universalism, even though Bersani posits it from a “minor,” queer position. Many question the extent to which those who are already “colonized, made into waste,” as postcolonial critic Neel Ahuja puts it, can make the refusal of this model of the self, through a deliberate embrace of death, legible against the disproportionate weight of the morbidity historically allotted to them both figuratively and materially. Bersani’s thinking seems better suited to those who are able to imagine having access to the privileged fantasy of mastery, even as their sexual marginalization prevents them from accessing it.

In this sense, Bersani serves to remind us that death is never one thing: it is diffused into a range of textures, times, and events. The speculative species-death posited as the political horizon for the Anthropocene, the locus of its call to action; the ongoing historical deaths of human populations caught up in necropolitical webs and toxic surroundings. Death appears here both ontological and historical guises: Death with a capital D and deaths with a pluralizing -s — the first, inevitable, the second, contingent on particular historical conditions.

It’s crucial, then, to receive the forms of time being transmitted by these other-than-human media — rocks, plastic, assholes — as expanding, counterpointing, and complicating human conceptions of historical time, not overwhelming them. This might seem obvious, but it’s easy to become overwhelmed by deep time. As John Playfair, a colleague of the Scottish geologist James Hutton, usually credited with the discovery of deep time, observed while looking at the rock formation that led Hutton to this discovery, “The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time.”

In the face of such depths, one might well muddle the difference between Death and deaths, might substitute affirmations of human inconsequentiality for correctives to inhuman abuses — might become persuaded that the heft of planetary time turns the differences between these positions into a matter of no importance.

But I’m pretty sure this isn’t the only story the rocks are telling us.

¤

Works cited and further reading:

Neel Ahuja, “Intimate Atmospheres: Queer Theory in a Time of Extinctions,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 21, no. 2-3 (2015): 365-385.

Stacey Alaimo, “Oceanic Origins, Plastic Activism, and New Materialism at Sea.” In Serenella Iovino and Serpil Oppermann, eds., Material Ecocriticism (University of Indiana Press, 2014).

Leo Bersani, “Is the Rectum a Grave?” October 43, “AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism” (1987): 197-222.

Leo Bersani, Tim Dean, Hal Foster, and Kaja Silverman, “A Conversation with Leo Bersani.” October 82 (1997): 3–16.

Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015).

Charles Lyell, A Second Visit to the United States of North America, volume II (London: John Murray, 1849).

Nicolas D. Mirzoeff, "It's Not The Anthropocene, It's The White Supremacy Scene; or, The Geological Color Line," in Richard Grusin (ed.), After Extinction (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, forthcoming 2017).

Scott Lauria Morgensen, “The Biopolitics of Settler Colonialism: Right Here, Right Now,” Settler Colonial Studies, vol. 1 no. 1 (2011).

Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011).

Jussi Parikka, A Geology of Media (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015).

Aaron Vansintjan, “Decolonizing nature, the academy, and Europe: An interview with Métis writer Zoe Todd,” Uneven Earth: A Conversation about Environmental Justice. http://www.unevenearth.org/2015/09/decolonizing-nature-the-academy-and-europe/

Sylvia Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation--An Argument,” CR: The New Centennial Review, vol. 3, no. 3 (2003): 257-337.

¤

LARB Contributor

Dana Luciano is Associate Professor of English and a former Director of the Women’s and Gender Studies Program at Georgetown University. Luciano is the author of Arranging Grief: Sacred Time and the Body in Nineteenth-Century America (NYU, 2007), which won the Modern Language Association’s First Book Prize in 2008. Her edited volumes include “Queer Inhumanisms,” a special issue of GLQ: The Journal of Gay and Lesbian Studies, co-edited with Mel Y. Chen (vol. 22 no. 2-3, spring/summer 2015) and Unsettled States: Nineteenth-Century American Literary Studies (NYU Press, 2014), co-edited with Ivy G. Wilson.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Speaking Substances: Bodies

The Oglala Lakota chief Red Cloud, who lived from 1822–1909, is distinguished by two unusual superlatives.

Speaking Substances: Ice

What can we learn about climate change by listening to a surprising sound: the sound of ice?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!