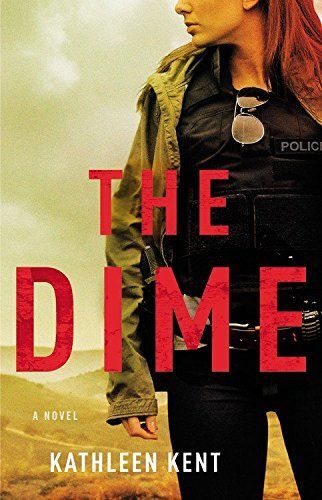

The Dime by Kathleen Kent. Mulholland Books. 352 pages.

AT FIRST GLANCE, The Dime, Kathleen Kent’s fourth novel, would appear to be a significant departure from her previous efforts — richly detailed historical romances like The Heretic’s Daughter (2008) and The Outcasts (2013), which feature bold young heroines confronting religious bigotry and sexual violence in frontier-age America. By contrast, The Dime is a gritty police thriller set in contemporary Texas, which kicks off a new series starring tough lesbian detective, Betty Rhyzyk. Yet, under the surface, there are distinct similarities. For all its high-tech suburban amenities, modern-day Dallas is not a far cry from the backwoods borderlands depicted in Kent’s earlier works. In the first place, everyone is armed to the teeth, and prevailing cultural attitudes contain large helpings of discrimination and intolerance, much of it justified by religious precept. Betty is subjected continually to sexist slights and homophobic putdowns, sometimes emanating from her male co-workers, and her ultimate enemy in the story is a vicious cult of God-fearing throwbacks who preach passivity and submission as the appropriate social posture for women. Needless to say, such a demeanor is not in Betty’s DNA.

Descended from a long line of New York City cops, including her abusive, alcoholic father and her doting uncle Benny, who acts as a kind of mentor to her, Betty — “Riz” to her friends — is a fiercely competitive hard case determined to prove her bona fides in a male-dominated world. After a stint as a Brooklyn beat cop, during which she witnesses the gruesome mass murder that opens the book, Betty moves to Dallas to take up a job as a narcotics detective. This relocation isn’t exactly her idea, since she shares her Uncle Benny’s view of the South as a wasteland full of “yahoos.” But her long-time romantic partner, Jackie, needs to be close to her aging mother — and Jackie is the only thing keeping Betty from tumbling into the kind of boozy, workaholic spiral that consumed her father and younger brother, who committed suicide while Betty was in training. As Betty puts it, “If not for Jackie, my idea of emotional self-help would be half a bottle of Jameson. I’d be living out of a suitcase, all my T-shirts would be black, and I’d still be buying underwear in the boys’ section of Target.”

Betty and Jackie make a convincing, likable couple, realistically if at times sentimentally rendered, and the scenes where Betty has to endure her drawling in-laws’ condescension are painfully funny. At a recent family dinner, as she sourly observes, “I had to sit through [an] angry tirade about ‘hom’sexiality’ leading to bestiality.” The only sympathetic soul among Jackie’s kin is great-uncle James Earle Walden, Betty’s initial description of whom deserves to be quoted at length because it gives a good taste of Kent’s acerbic prose, as well as her ability to capture the core of a character in a few incisive sentences:

James Earle Walden, a Vietnam War vet who has struggled with alcoholism his whole life. He sits next to me with a prop of club soda beside his plate, white-knuckling his way through another family gathering. He smells of decades of nicotine, seeping through every pore, his overly long hair slicked back with combed-through layers of drugstore hair gel. His hands shake as he brings a rib to his mouth, splashing comets of grease onto his shirt. But there is a quiet, wounded-bear quality about him, and his efforts to appear normal, to make polite conversation while trying to mask with cautious smiles the ruined state of his teeth, make me want to hold him and weep.

Betty’s narration throughout, at once amiable and edgy, is a continuous pleasure to read, even when the story veers into dark and ugly terrain.

This descent into darkness begins with a botched undercover operation, overseen by Betty in coordination with federal agents, that is designed to prove the collusion between a wealthy Dallas meth dealer and Tomás “El Gitano” Ruiz, a notorious enforcer for a Mexican drug cartel. After an unforeseen shootout leaves three people dead, Betty and her partner, Seth “Riot” Dutton, start probing Ruiz’s local connections, especially his sometime girlfriend, a Chinese-American masseuse — who is herself murdered in a particularly sadistic way Betty doubts is the cartel’s work, despite their renowned brutality. Not long after, Ruiz himself turns up dead, his severed head deposited on Betty and Jackie’s doorstep, as the menace becomes suddenly personal in nature, with a mysterious stalker — perhaps from a rival meth-dealing gang — tracking Betty and interfering in her investigation.

These plot shifts come hard and fast, causing a kind of readerly whiplash as the case is persistently rethought by Betty, Seth, and their small handful of (male) co-workers, including a macho homicide detective who believes Betty and her narco crew are intruding on his turf. As in any good police procedural, the day-to-day details of team camaraderie and inter-agency rivalry are effectively conveyed, with Betty holding her own in the face of largely covert but occasionally blatant acts of misogyny and harassment. One detective, “a scrawny, barely-made-it-through-community-college type, likes putting a sexual spin on everything, typical cop bustah-balls humor. But he seems to take special glee in skating on the edge of protocol with me.” Luckily, Seth is a real mensch, always supportive and in no way threatened by her gender or sexuality; indeed, he and Betty make an appealing duo, swapping stories of their romantic travails in a way that borders on the flirtatious. Their jocular, buddy-movie banter gives the story some spice, which the reader misses once events, halfway through, conspire to separate them.

Without giving too much away, I have to admit that I found the second half of the novel, with its abrupt switch of adversary from drug dealers to religious maniacs, both unsatisfying and overdone. While the tale remains readable throughout, due largely to the unflagging energy of Betty’s shrewd, irascible voice, the plot rapidly devolves into a strained, at times cartoonish clash of worldviews, loading too much thematic baggage onto what was a proficient exercise in Southern-fried noir. Moreover, we are reminded, once too often, of Betty’s plucky resilience, her ability to take a punch and come up fighting: over the course of several chapters, she is drugged, beaten, hobbled, and otherwise brutalized, and the cumulative effect is exhausting. Yes, hardboiled male sleuths are often similarly tested, subjected to trials designed to break their wills, but a cliché is a cliché regardless.

One wonders, after the gauntlet she is compelled to endure, how Betty will manage to survive a long series. The Dime has a very high body count, with two of her co-workers dead by the end and two others sidelined with injuries. I for one hope that Kent ratchets down the stakes in subsequent volumes, allowing Betty’s cases to develop their own quirky logic without feeling the need to personalize them, to make the focus all about our heroine’s gritty ability to absorb punishment. That said, The Dime concludes with one of the cult masterminds still on the lam, and with loose ends suggesting that the group has penetrated the Dallas police force, so it’s entirely possible the next novel will simply take up where this one leaves off. If that’s the case, readers should certainly enjoy watching Betty’s relationship with her two partners — personal and professional — develop further, and attending to her hip, impertinent narration should definitely have its pleasures. But I fear the whole enterprise may be in danger of burning itself out prematurely, overwhelmed by the sheer adrenalized pace.

And that would be a shame, because Kent has shown herself to be both an effective storyteller and an acute social observer, with a sharp eye for Texas-sized absurdities — my favorite being an improbable standoff between a handful of the cartel’s gunmen, armed with automatic weapons, and a ragtag band of Civil War reenactors, outfitted with muskets and bayonets. I hope this series manages to evoke more such memorable moments without always feeling the need to trot out Big Issues like religious zealotry. Just following Betty through her day-to-day grind ought to provide Kent with endless opportunities to comment on the subtle effects of homophobia and sexism; it really isn’t necessary to summon up a pack of Old Testament monsters to do that.

¤

LARB Contributor

Rob Latham is the author of Consuming Youth: Vampires, Cyborgs, and the Culture of Consumption (Chicago, 2002), co-editor of the Wesleyan Anthology of Science Fiction (2010), and editor of The Oxford Handbook of Science Fiction (2014) and Science Fiction Criticism: An Anthology of Essential Writings (2017).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Southern Crazy

Lisa Turner discusses her new novel, “Devil Sent the Rain.”

Tender Noir

Kim Fay reviews “Darkness for the Bastards of Pizzofalcone” by Maurizio de Giovanni.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!