Soul and Dual: “Dothead” by Amit Majmudar

Caitlin Doyle considers “Dothead” by Amit Majmudar.

By Caitlin DoyleOctober 12, 2016

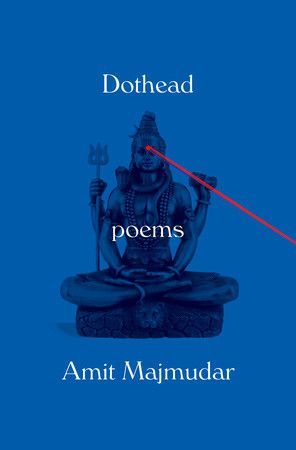

Dothead by Amit Majmudar. Knopf. 120 pages.

THE EPIGRAPH of Amit Majmudar’s new poetry collection Dothead comes from Dr. Seuss: “It is fun to have fun / But you have to know how.” Majmudar, whose parents emigrated from India, frequently writes about American identity, ethnic otherness, and the cost of conflict on the global scale. Though Seuss’s lines may seem like an unusual touchstone for a book that explores such weighty subjects, they capture a central element of Majmudar’s writing. In Dothead and his previous collections, 0˚, 0˚ and Heaven and Earth, Majmudar reveals himself as a poet for whom nothing is more serious than play, a quality that keeps even his most politically oriented work rooted in poetry rather than polemics. He teases language out of hiding in order to uncover fresh meaning from the startling relationships between words.

“To the Hyphenated Poets,” one of the most memorable poems in the collection, demonstrates how Majmudar’s wordplay magnifies the gravity of his material. Addressing poets with whom he shares multiple cultural identities, he urges them to become:

a many-minded mongrel,

the line’s renewal,

self-made and twofold,

soul and dual.

Through Majmudar’s punning reference to the “line’s renewal,” in which we discern both an evocation of the poetic “line” and the ancestral “line,” he suggests a link between artistic progress and a creator’s connection to his or her origins. “Soul” contains hints of “sole,” an effect that subtly pulls against the word “dual.” Even as the poem encourages “hyphenated poets” to embrace their dual selves, Majmudar implies that the intactness of one’s soul depends on preventing those selves from losing their distinction. Of course, we also hear “duel” in “dual,” further heightening our sense of the poets’ struggle.

If his emphasis on linguistic play is an unusual trait among American poets of his generation (Majmudar was born in 1979), it’s far from the only quality that sets him apart. He has attained cross-genre success with the publication of two acclaimed novels, Partitions and The Abundance, and he earns his living as a diagnostic nuclear radiologist. His medical background informs his poetry in salient ways. In the final image of “Training Course,” Majmudar evokes the human longing for spiritual presence amid the seemingly objective world of science: “Trainee places left hand on switch, right hand on heart, / And waits for monkey, preoccupied with naked tube light, to meet eyes.”

“Logomachia,” a 16-page poem in sections, centers on the relationship between scientific knowledge and faith. Majmudar describes the experience of holding up an x-ray for examination: “Each pixel: a point geometry / defines dimensionless, no height, no width, no death.” By replacing the expected word “depth” with “death,” he spurs us to consider what may be missing when we allow the methods of science to overly determine our lives. The facts of a diagnosis, he suggests, don’t necessarily allow us to grasp mortality.

A reader focused on Majmudar’s background might mistake him as a poet defined by those aspects of his work that seem, on the surface, most related to his biography. But his breadth of subject matter spans sex, popular culture, art, capitalism, history, the natural world, and more. In Dothead, several of the most striking poems exist outside of strictly political or scientific considerations, including “Pattern and Snarl,” in which Majmudar meditates on order and entropy:

Life likes a little mess. All patterns need a snarl.

The best patterns know how best to heed a snarl.

Every high style, every strict form was once nonce.

The best way to save a snagged pattern? Repeat the snarl.

Written as a sonzal, which combines the sonnet and ghazal forms, the poem progresses smoothly until Majmudar delivers a self-reflexive tongue-in-cheek “snarl” in its pattern; after rhyming one of the lines on “again,” he repeats the effect a few lines later: “I never intended […] to rhyme on again again.” He arrives finally at an insight that we see reflected in his larger body of work: “sometimes it’s the snarl that adorns the pattern.” Throughout Dothead, we watch Majmudar make and deftly break patterns as he invents nonce forms and engages with established formal modes in innovative ways. Yet he also explores the risks and limitations of an art that relies too much on technical acumen.

In “Steep Ascension,” Majmudar recounts visiting the poet John Hollander in the hospital. Hollander, whose work has been a major influence on Majmudar, says: “Back when I was young […] it seemed / the art and the artful were one and the same.” Later, when he addresses Majmudar by name, we feel the urgency of his reconsideration:

Listen, Amit — that’s not what it’s about.

It isn’t worth it if it isn’t bought

with suffering. The best of us have written

maybe a dozen lines that tap the root.

The rest? Bout-rimes with dead men, overwrought.

Tracing Hollander’s growth from a young man to a mature poet who has realized, perhaps too late, that art “isn’t worth it if it isn’t bought / with suffering,” Majmudar invites us to look closely at the relationship between “art” and “artfulness” in his own work and, by extension, poetry at large.

When Majmudar attempts to console Hollander, we sense that he is also speaking to himself: “I for one will hold your labors dear, / the music of meaning, the artistry that dares / to conjure walls that it might conjure doors.” If “walls” represent a mastery of technique, “doors” suggest magnitude and emotional depth. Majmudar’s use of the word “might” in the final line evokes the possible failures of a poet who relies too much on being “artful” rather than trying to “tap the root” of human experience. The risk of a creative process that “dares / to conjure walls” through technical acuity, Majmudar implies, is that the creator might ultimately fail to “conjure doors,” thus leaving readers trapped in an airless room.

Apart from its formal brilliance, Dothead is also defined by Majmudar’s emphasis on inherited cultural narratives, particularly those associated with religion, mythology, art, and classical literature. “Abecedarian,” a stunning 11-page prose poem, offers a retelling of the Adam and Eve tale focused on oral sex, interspersing their relationship with his own adolescent sexual explorations. In “The Enduring Appeal of the Western Canon,” Majmudar prompts us to question the interaction between reality and mythos in the stories we receive about revered canonical figures and celebrated works of art. When the speaker says that “The blackberries in the Dutch painter Jan van Os’s still life / Cause ants to abandon genuine grains of sugar / And head single file for the wall,” we can’t be sure if that’s a known fact, a piece of popular lore, or a complete invention on the poet’s part.

We find our uncertainty addressed in the next line: “Look up ‘Van Os Ants’ on YouTube if you don’t believe me.” Readers who, like this reviewer, can’t resist taking up Majmudar’s challenge won’t yield any success from a search for “Van Os Ants.” Yet even though the lack of video proof suggests that the ant anecdote has been fabricated, we feel nagged by other possibilities. Did the video once exist only to be removed? Maybe a more extensive search would uncover it buried in YouTube’s archives? The speaker’s statement about Jan van Os’s still life, like several of the poem’s other details, can neither be proven nor disproven, an effect that heightens our sense of the ever-shifting boundary between truth and fiction in the cultural stories we absorb.

In “Lineage,” another poem that explores the implications of our inherited narratives, Majmudar conjures a creation story of sorts for the United States’s favorite form of weaponry:

And Flintlock begat Springfield, the breech birth,

And Springfield begat Enfield, and Enfield begat Gatling,

And Gatling begat Maxim, who begat Rat, who begat

The blessed Twin boys Tat and Tat

Once again, Majmudar merges lightness and gravitas to amplify the gut punch of the subject matter. His blending of language from the Bible with childhood’s nursery-rhyme cadences underscores one of the piece’s most disturbing suggestions: that gun worship has long possessed a religious fervor in American society, and that children often absorb the most devastating impacts of this phenomenon, both as firearm acolytes created in the image of the adults around them and as victims of gun violence.

Nowhere does Majmudar’s gift for linguistic play shine with greater force than in “1914: The Name Game,” which stands out in Dothead as a poem that epitomizes his strengths. He packs the lines with names of historical figures and draws unpredictable, often sonically driven, connections between them. Once the profusion of names has gathered a giddy momentum, the poem turns: “It’s time for the name game, children, the same game / that launched a thousand dreadnoughts / that launched a thousand dead men on the oil-dark sea.” Majmudar offers a dark twist on Christopher Marlowe’s much-quoted description of Helen of Troy as “the face that launched a thousand ships.” We also hear Homer’s “wine-dark” sea echoing through Majmudar’s “oil-dark sea,” a detail that collapses ancient history with modern warfare by evoking the role of oil in international conflict.

The ending of “1914: The Name Game” is among the most compelling final stanzas to be found either in Dothead or any recent collection of American poetry. The poem’s speaker imagines, and then directly addresses, an archetypal World War I mother who must wait to hear news of her son’s fate:

Marnefully sobbing, hiccupping Ypres Ypres,

The mum of the lad (she, unidentified; he unidentifiable)

Expects no Clemenceau from stern War.

A nor’waster falls into the Gare de L’Waste.

Don’t worry, O generic Mum-of-Lad, O mute

Liverpudlian Hecuba in your unisex ankle-length

Garbadine coat: Bad news has Gavrilo Princip aim.

The War Office telegram will target you by name.

These lines show us one of the United States’s best poets at his best. Through a combination of mixed diction and syntactical mock-grandeur, both of which intensify the play of linguistic humor against serious content, Majmudar achieves a tonal complexity that enhances the closing couplet’s devastating impact. His reference to Gavrilo Princip, the man who assassinated the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife, adds another layer to the poem’s exploration of the ambivalent value of possessing a name. As the last two lines suggest, if our names mark us as individuals with specific identities, they also bind us to other people in a way that makes us a “target” for forces beyond our control.

It’s thrilling enough to discover a poet exceptionally gifted with any one of Majmudar’s individual strengths: his technical prowess, his balance of erudition and accessibility, his merging of wit and profundity, and his adeptness at combining narrative modes with exquisite lyricism. Encountering a poet in whom all of these facilities, and more, unite to form a single gift reminds us of poetry’s most essential powers. Whether or not we believe that ants abandon “genuine grains of sugar” for the blackberries in Jan van Os’s still life, we can’t help but find in that image an emblem of Majmudar’s indelible work. He uses words with such precision and imagination that their glimmer exceeds the world they represent.

¤

LARB Contributor

Caitlin Doyle’s poems, reviews, and essays have appeared in The Atlantic, Boston Review, The Threepenny Review, Black Warrior Review, Best New Poets, and other journals and anthologies. She has held Writer-In-Residence teaching positions at Penn State, St. Albans School, and Interlochen Arts Academy. Caitlin’s awards and fellowships include a Yaddo residency, the Margaret Bridgman Scholarship through the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Amy Award in Poetry through Poets & Writers, a MacDowell fellowship, and Writer-In-Residence terms at the James Merrill House and the Jack Kerouac House. She is currently pursuing her PhD as an Elliston Fellow in Poetry at the University of Cincinnati, where she teaches in the department of English and Comparative Literature. You can visit her website at this link: http://caitlindoylepoetry.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Recuperating Exile: Ocean Vuong’s “Night Sky With Exit Wounds”

“Night Sky With Exit Wounds” is a debut collection of poetry by Ocean Vuong that explores identity, the immigrant experience, and the impact of exile.

Sifting Through “Mortal Trash”

John Domini on Kim Addonizio's "Mortal Trash" and "Bukowski in a Sundress".

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!