Someone Always Takes Me Home: On Howard Fishman’s “To Anyone Who Ever Asks”

Chris Molnar reviews Howard Fishman’s “To Anyone Who Ever Asks: The Life, Music, and Mystery of Connie Converse.”

By Chris MolnarJune 21, 2023

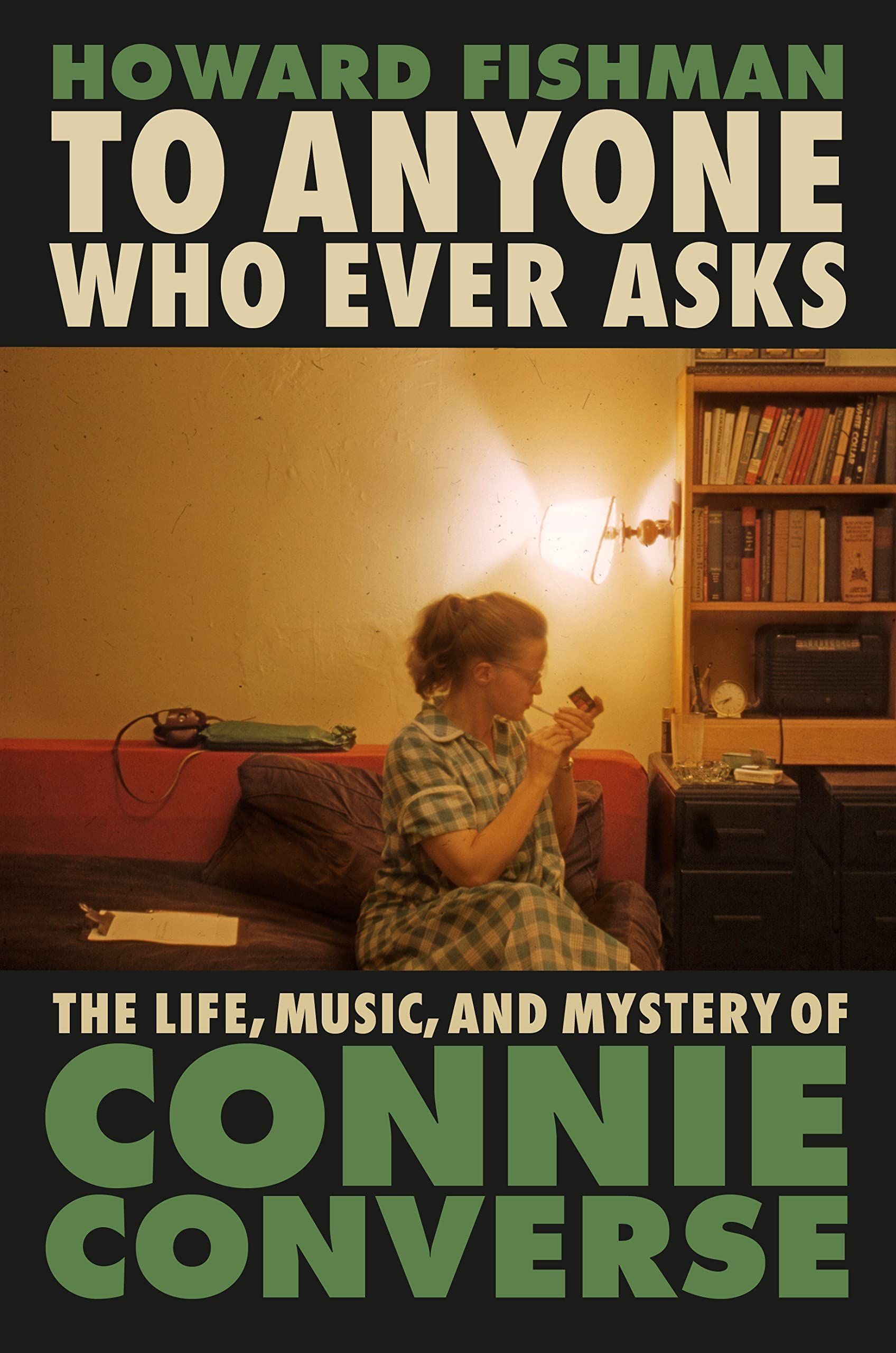

To Anyone Who Ever Asks: The Life, Music, and Mystery of Connie Converse by Howard Fishman. Dutton. 576 pages.

CONNIE CONVERSE is remembered now, if at all, as a rediscovered relic of blog-era music oddity. Like Rodriguez, Donnie and Joe Emerson, Sibylle Baier, Lavender Country, or Converse’s near-contemporary and kindred spirit, Molly Drake, the cracks she slipped through became her calling card. Converse was notable for preserving a greater level of obscurity more extreme than any of the others: recordings never commercially available; no connections to any scene or famous figure; being a guitar-playing singer-songwriter (and home-taper) in the early 1950s, before such a thing existed, who played only among friends before dropping out of music in the 1960s and ultimately disappearing shortly after. It was not until the 2000s that some of her work was finally made available for those who were never in a room with her.

This is how musician and New Yorker contributor Howard Fishman came across Converse: overhearing How Sad, How Lovely, her first commercially available album, at a party in 2010, just a year after its long-delayed release. This chance encounter (itself born of a chance encounter, that of recording engineer Dan Dzula overhearing cartoonist and animator Gene Deitch play a song he recorded of Converse’s in the 1950s on WNYC in 2004) led to an escalating obsession, with Fishman visiting the home of Converse’s brother, exploring her archives there, arranging concerts of her unreleased music, writing a Converse-centric play, and ultimately embarking on 10 years of travel, research, and writing that would eventually yield To Anyone Who Ever Asks: The Life, Music, and Mystery of Connie Converse (2023), a totemic accomplishment and indispensable guide to a vast body of work that is—outside of 20-odd songs on Spotify and brief “Did You Know?” and “Unexplained Disappearances!” articles of varying veracity—glimpsable for the first time in its pages.

The subtle shading of a truly quotidian life and the gaps in the narrative that, for all his diligence, Fishman could not fill in invite the imagination and make To Anyone Who Ever Asks an oddly personal experience for such an extensive and well-researched biography. Born in 1924 into an insular New England family (distantly related to the shoe Converses) marked by a striking level of creepy repression and secrecy, Elizabeth Converse—only known as Connie during her New York songwriting years—attended Mount Holyoke, her mother’s alma mater, but dropped out after the gruesome suicide of her best friend. Upon leaving school, she dropped off the face of the earth—possibly to travel across the country—a harbinger of things to come.

Converse resurfaced a year later, taking a secretarial job in 1945 at the Institute of Pacific Relations (IPR), a left-leaning NGO headquartered in Manhattan. The questions here multiply; the more modern she appears to become (college dropout, drinking and smoking, a footloose traveler, dabbler, proudly single, with friends across the gender spectrum, her own aesthetic and hygiene always unusual, all in rebellion against her deeply conservative family), the more out of step she already seems with her times. How did she get the job? How did she—in the 1940s—fall into this creative milieu, let alone guitar-based songwriting? And yet, here she is, hobnobbing with unheralded bohemians and Asian diasporic co-workers (the IPR specialized in relations between Pacific Rim countries), living a vibrant single life unavailable anywhere else in such a deeply conservative country and era. Converse, seen sidelong by the nonagenarian witnesses and children thereof that Fishman can find, is living a life familiar to anyone who has spent their twenties in Manhattan: late nights, shifting friend groups, nascent romances, and artistic experimentation. She edits and publishes remarkable papers on the recent history of countries like Singapore or Micronesia for her work. Her childhood violin is swapped for the guitar, and in a pre-folk, pre-coffeehouse-scene Greenwich Village, Converse begins to write and perform songs at social gatherings of various creative and creative-adjacent types, redolent with a sense of Mad Men–vintage New York, not exactly plugged in to the creative mainline but full of primordial upheaval nonetheless.

There is the tiniest brush with fame when Gene Deitch records her and somehow helps arrange an unrecorded televised appearance on CBS’s Morning Show with Walter Cronkite in 1954, despite Converse’s lack of professional recording or performing credentials. But the exposure leads nowhere; under the aegis of more high-art friends, she migrates away from idiosyncratic, entertaining guitar music to headier spheres, working on an opera and related lieder, moving Uptown to room with her brutish older brother and his family right as the folk scene emerges next to her old apartment in the Village. The communist-leaning IPR begins to dissolve as the Red Scare sets in. She starts working for an offset printer—a technology in its infancy, Fishman makes sure to note, underlining an idea of Converse as far-seeing in all respects.

Exhausted from the seeming failure of the job, the music, her living situation, and a relationship, Converse moves to Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1961 to be near her younger brother, with whom she had corresponded about music and sent self-recorded tapes. But she finds him distracted by work (Philip Converse was a notable sociologist at the University of Michigan) and his young children. She herself becomes occupied editing the journal of the Center for Research on Conflict Resolution, an IPR-like lefty “peace studies” haven within U of M—auspicious in the ferment of the 1960s, where she throws herself into local progressive causes as music falls by the wayside. Converse seemingly burns out altogether in the 1970s, amid a continuing lack of recognition for her art and, later, her relentless work at the Journal of Conflict Resolution—which leaves town after the center is dissolved in a Nixon-era repeat of the IPR-McCarthy hearings, failing to invite Converse, the uncredentialed engine behind it all. After a final trip to England, funded by a group of friends grateful for her years of thoughtful attention, she writes farewells and drives off into history.

All of this is written with Robert Caro–esque thoroughness; over 100 pages of footnotes and appendices detail the children of friends of friends interviewed, strangers all across the country roused with the odd query—do they know who Connie Converse is? The exhaustive care with which Fishman approaches his subject is itself hypnotic, even devastating. There is no way he could have known, starting to write this book, the breadth of Converse’s life, and yet she still remains perhaps the least (previously) notable subject of any biography this size. Outsider artists, even when their work balloons in value, are rarely considered worth the trouble to research so doggedly. Where are the biographies of Royal Robertson, or Mary Ann Willson, or even Jandek? This is the tension and narrative of To Anyone Who Ever Asks, and what makes it so powerful—Converse is a greater tragic hero than any person you’ve heard of, absolutely disjointed from her time, unsettled and without ability to settle for any job, life, or medium, whose talents are unlikely to ever be revealed in full.

And for all that, the phrase “outsider artist” is hardly applicable here, given that it connotes some kind of monomaniacal automatic creation, fully separated from society: a janitor like Henry Darger or a nanny like Vivian Maier, creating in secret and only discovered after their death, or a figure like Simon Rodia or Daniel Johnston, icons beloved in their lifetimes in part because of an irrepressible eccentricity and separateness. Converse is neither. She is simultaneously singular and indistinguishable from any other aspiring artist, ahead of her time and inextricable from her communities. As she works thankless day jobs, her art is met not with critical rejection but silence. If anything, she resembles Cesárea Tinajero, the lost legendary poet of a nonverbal poem in Roberto Bolaño’s novel The Savage Detectives (1998), brought to life, a mysterious embodiment of the fact that there are always other worlds other than the one we live in, side canons, forgotten geniuses, and that notability means nothing at all.

That sense of a person unseen in her day and afterwards (Dan Dzula’s record label, established in 2009 to publish her music, no longer produces records), still uncommercial and out of joint, makes Converse’s accomplishments seem unimaginably vast and somehow more relatable. She is an ideal protagonist, both audience stand-in and unapproachable hero whom we—and Fishman—feel protective of, our unsung genius. For not only did Connie Converse, ex nihilo, essentially invent the American “singer-songwriter,” with songs still durably unusual, all before the impact of Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music or the folk era, but she also wrote complex and accomplished art songs; full operas of which rehearsal tapes exist; lost novels of tantalizing description; voluminous correspondence and diaries, disarmingly vulnerable, engaging and erudite; a children’s book for her nephews; elaborate games, including one built as a statistical harvester for the purposes of conflict study at the CRCR; treatises on sociology, Asian history, international relations, and anti-racism, all of which Fishman passes by the eye of suitably impressed modern experts (“My goodness!” says the author of 2018’s White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism when confronted with Converse’s 1969 proto-BLM manifesto), all of it part of a restless need to discover and solve and make the world a better place despite having no place in it, no place even in her own head, despite so much—all—of her exuberant creation ignored or destroyed.

Her guitar songs—which make up How Sad, How Lovely and the more recent Sad Lady EP (2020), the only two collections extant of her recorded work (aside from an album of her piano compositions performed by an ensemble Fishman organized)—reflect this and more; they are oblique yet unaffected, deceptively simple. “Roving Woman” begins: “People say a roving woman / is likely not to be better than she ought to be, / so, when I stray away from where I’ve got to be, / someone always takes me home.” There is a strangeness to the phrasing that augments the light, wryly melancholy melody and vocal. “[L]ikely not to be better than she ought to be” is difficult to untangle, especially when delivered in a sighingly cheery folk-pop song less than three minutes long. But it’s precisely that difficulty that helps it linger in the mind.

Like many of her lyrics, it’s a riddle and secret key, and as Fishman explores her roots in New England, her life in Manhattan, and finally her resettling in Ann Arbor (where he speculates about her asking a young Iggy Pop, who worked at the local record store, for recommendations), we gain a rich sense of Converse and her world without losing any of that mystery. There are aspects of true crime, anthropology, and oral history here, but it’s always straightforwardly Connie’s story, her motivations and feelings suggested but hidden. Her workaday life is all too familiar: jobs that disrespect the energy we put into them, beloved if unexceptional friends, never getting a big break—or even a small one. The mystery is how she did keep going, and why did it never quite come together? What happened to Connie Converse? To Anyone Who Ever Asks is both frustrating and satisfying in that, for all its breadth and exhaustiveness (even between the galley and final published product, the research continued, leading to the most changes in a near-finished book in Dutton’s history), we don’t find out.

And yet, thanks to her music’s emergence—and to this unique and remarkable work—Converse as a person reverberates, finally. Fishman’s argument is that capital-A Art is important; that to seriously dedicate oneself to personal expression is a profound rebellion against a society that wants one to be a cog for the status quo; and that such art can change the world by showing how a human being does not have to conform, and can instead give themselves over to beauty and joy. Art not as a hobby or whim but a way of looking at the world, a steely yet gimlet-eyed refusal to comply on any terms other than one’s own. She may have struggled, greatly, but she embodies more than perhaps anyone this purely internal journey of creation, divorced from the corrupting attention of capital—art not as content, not as product, not madness, but feelings expressed with obsessive thought, thoughts expressed with gracious feeling. Art as one of the high things that human beings can offer each other—one expression of many that Connie Converse explored in a restless journey to alter the course of the world, and which, thanks to Howard Fishman, succeeds.

¤

LARB Contributor

Chris Molnar is co-founder and publisher of Archway Editions, as well as co-founder of the Writer’s Block bookshop in Las Vegas.

LARB Staff Recommendations

When a White Man Writes a Good Book About Africa: On Tim Cocks’s “Lagos”

Kovie Biakolo contemplates Tim Cocks’s 2022 book “Lagos: Supernatural City.”

Ball Is Cry!! On Katie Heindl’s “Basketball Feelings”

Liz Wolfson profiles Katie Heindl, author of the sports Substack “Basketball Feelings.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!