Sleepwalking to Madness in Mid-Century America: On Audrey Clare Farley’s “Girls and Their Monsters”

Ellen Wayland-Smith is haunted by Audrey Clare Farley’s exposé, in “Girls and Their Monsters: The Genain Quadruplets and the Making of Madness in America,” of white American mid-century pathologies.

By Ellen Wayland-SmithJune 13, 2023

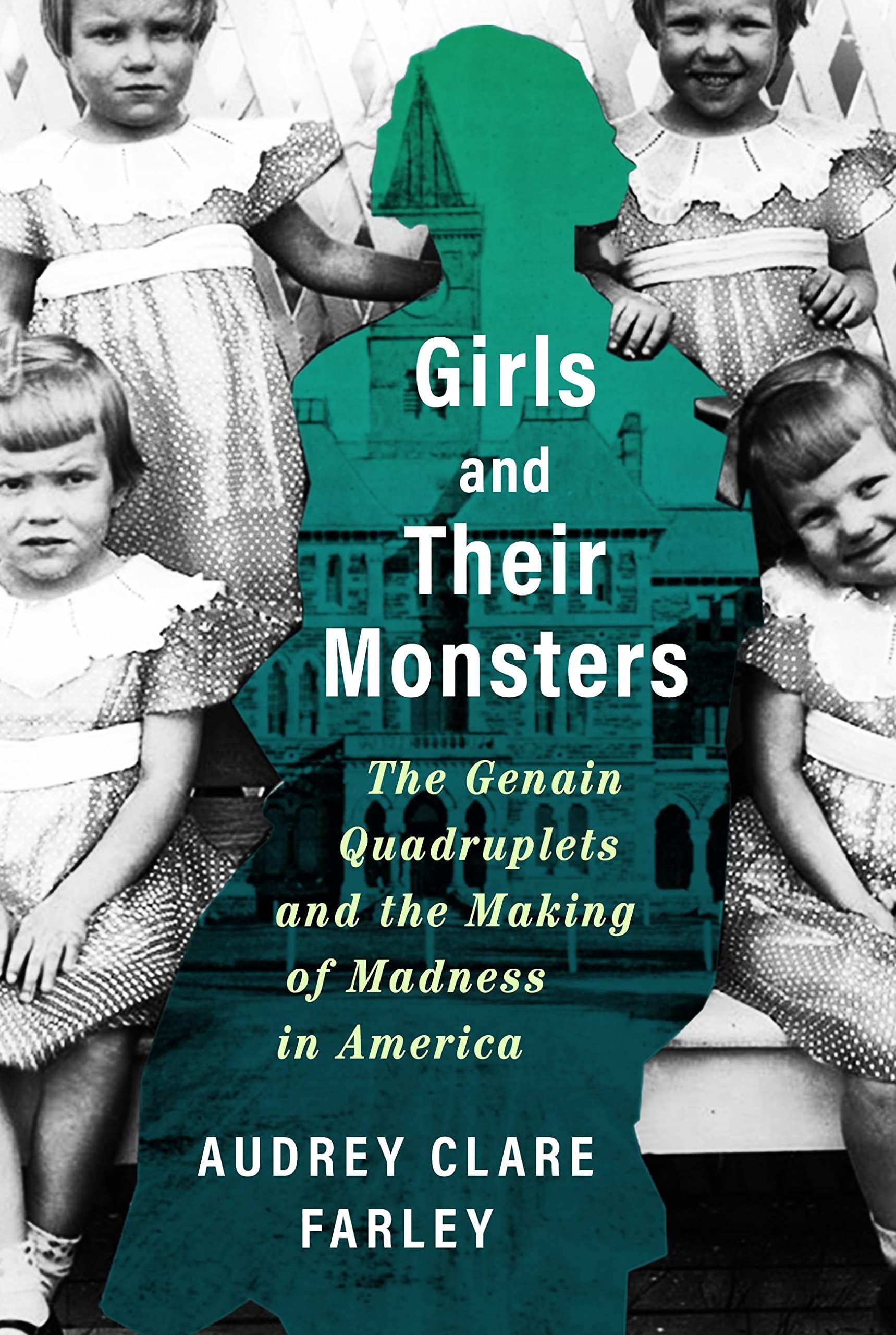

Girls and Their Monsters: The Genain Quadruplets and the Making of Madness in America by Audrey Clare Farley. Hachette. 304 pages.

ON MAY 19, 1930, Sadie Morlok of Lansing, Michigan, gave birth to identical quadruplet girls. Sarah, Edna, Wilma, and Helen were local celebrities from the get-go: reporters hovered in the hospital waiting room hoping to bribe nurses for the weight and length of the newborns; photographers snuck into the nursery to snap pictures. City officials offered the family free housing for a year, Lansing businessmen opened college savings accounts, and local seamstresses sewed diapers and blankets. In the bleak post-Depression years, everyone was looking for a silver lining—and the Morlok sisters fit the bill as the embodiment of cheerful white American girlhood. The family was quick to comply with public expectations. Sadie enrolled the girls in singing and dancing lessons, and took the quartet on the road, gussied up in frilly short dresses and ribboned curls. In an age of eugenics—a science their German-born father Carl put great faith in—the quadruplets doubled as examples of what wholesome breeding among strong white American stock could do for the country.

By their early twenties, all four of the quadruplets had succumbed to schizophrenia, and three of the four would spend the rest of their lives, until their deaths in the early 2000s, in and out of state mental hospitals and halfway houses. Once prized for their Shirley Temple dimples and shiny matching tap shoes, the sisters’ greatest attraction became something else entirely: they offered psychologists “[a]n unprecedented opportunity for the study of heredity and environment in mental illness,” according to a 1964 book review published in The Journal of the American Medical Association. In 1954, when the sisters were 24 years old, their case came to the attention of Dr. David Rosenthal, a schizophrenia expert at the National Institute of Mental Health in Washington, DC. He secured the sisters’ transfer to NIMH’s facility where, over the next three years, they would be studied by a team of more than 30 medical doctors, social workers, and psychiatrists. In 1963, these studies culminated in Rosenthal’s 600-page pseudonymous landmark study, The Genain Quadruplets: A Case Study and Theoretical Analysis of Heredity and Environment in Schizophrenia.

How was it possible that these sisters, once hailed as shining examples of American genetic fitness, had joined the ranks of the so-called eugenically unfit, emblems of degeneracy and a drain on the taxpayer’s wallet? This is the fascinating story that Audrey Clare Farley’s new book, Girls and Their Monsters: The Genain Quadruplets and the Making of Madness in America, sets out to investigate. In constructing an intimate portrait of the decades-long relationship between the Morlok family and the federally funded scientists who studied them, Farley examines the way American institutions and culture crucially shaped the construction of madness at mid-century. In the process, she raises vital questions about the nature of “psychosis” itself, both individual and collective.

¤

Once at NIHM headquarters, all six members of the Morlok family underwent extensive biological and psychological testing, from blood samples, fingerprinting, EEGs, and galvanic skin response tests to psychiatric interviews, family histories, handwriting analyses, draw-a-person and doll play tests, and Rorschach protocols. The researchers were especially on the lookout for signs of hereditary madness in the parents, and Carl, in particular, did not disappoint: one of his uncles was “known to be psychotic”; his eldest brother Bill had been diagnosed a “moron type”; and “there was a cousin who’d masturbated in public and been deported back to Germany.”

And yet, as NIHM’s staff slowly discovered—and as Farley, with access to letters, diaries, and firsthand interviews with family members, was able retrospectively to verify—the pathological dynamics within the Morlok household were far more disturbing than anything passed down in Sadie and Carl’s DNA. Carl was not simply an authoritarian racist but a literal Nazi, rooting for the Third Reich even after the United States’ entry into World War II. Sadie reported having to hush his fascist rantings in public, lest he get himself deported (“You’re American, now,” she would scold). Carl’s authoritarian tendencies received apparent outside affirmation when he was elected constable of Lansing shortly after his daughters’ birth, a role he fulfilled with shambolic inattention, yet which gave him access to a gun, a badge, and the borrowed authority of the Lansing Police Department.

Carl was a drunk and borderline sex addict, rejecting Sadie as a “bitch dog” whenever she made amorous advances and instead outsourcing his pleasure to other women (including at least two of the countless young nannies the couple hired to care for their brood). He struggled with impotence. Inside the home, he was obsessed with securing his daughters’ sexual purity—a pursuit Sadie wholeheartedly supported. The girls were scrupulously forbidden from forming friendships at school, their bodies and actions monitored for signs of sexual perversity. When Helen and Wilma were caught masturbating, Carl and Sadie sought first to cure them of the filthy habit by beating them and coating their genitalia with carbolic acid before resorting, finally, to circumcision—a common medical procedure at the time for young women diagnosed as “oversexed.”

While dismissing the girls’ actual experiences of sexual molestation and assault—Helen was routinely fondled by an elementary school janitor and, later, a teacher; Edna was sexually assaulted in an elevator—Carl stalked the girls within the home. He forbade them from closing the bathroom door; watched them as they got undressed at night; routinely groped their breasts and buttocks, claiming he needed to “gauge how they’d react on dates when older.” Sadie turned a blind eye, claiming that the girls’ resistance to their father’s sexual advances was proof positive that they were “good girls.” Throughout his daughters’ interactions with the medical establishment—first as masturbation addicts, then as schizophrenics—Carl’s main concern was to keep the whole thing under wraps, threatening to kill himself and the rest of the family if the shameful news of his daughters’ “sickness” were to be leaked to the public: they had a local, and even national, reputation to keep up.

If the harrowing nature of the girls’ upbringing was occasionally remarked upon by staff members at NIHM, in the end psychiatry’s ingrained patriarchal prejudices normalized much of what transpired within the family, or attributed the dysfunction to Sadie’s poor mothering. Within psychoanalysis, popular theories traced schizophrenia to an overprotective “schizophrenogenic mother.” Sadie was duly pathologized, and Carl’s abusive actions glossed over. Sadie’s caseworker, primed by the field to be “on the hunt for an overanxious mother,” unsurprisingly found one; the quadruplets “devoted themselves to living out the mother’s mandates and thus sacrificed their own personalities,” she concluded. Meanwhile, Carl’s “higher-than-average preference for domination,” as measured by a Parental Attitude Research Instrument (to the statement “Some children are just so bad they must be taught to fear adults for their own good,” Carl checked “strongly agree”), was normalized as the natural response of a weak ego needing to prop itself up through the “over-control [of] external situations.” Indeed, one reason caseworkers were inclined to excuse Carl’s disturbing behavior was that they suspected he had himself been raised by an emasculating, domineering mother, and thus deserved sympathy rather than blame. Behind every bad man, the logic ran, there was always an even worse mother.

¤

Yet, while this behind-the-scenes exposé of family dysfunction is mesmerizing in its own perverse way, Farley’s major achievement in this book lies in her patient unpacking of how mid-century psychiatry was fatally blind to the fact that the quadruplets’ sickness mirrored pathologies in American culture. The psychosis-inducing dynamics endured by the Morlok sisters in their home were not, she argues, entirely private in nature but, rather, the eerie mirror image of the nation’s own pathological “racial and religious commitments” to white supremacy and authoritarian Christian purity culture.

The most compelling sections of the book, then, are those where Farley juxtaposes the white gaze of mid-century pharma-psychiatry with competing traditions of Black, Marxist, and feminist-centered psychoanalysis that, while available to Rosenthal and his NIHM colleagues, predictably never factored into the definitive 1963 case study. Rosenthal was not himself racist, but he was part of a medical and political institutional apparatus that decidedly was, its unacknowledged “racial commitments” informing how psychosis was framed during the years of the Civil Rights Movement. Building on earlier 19th-century pseudoscience that had coined the term drapetomania to describe the “insane” desire of certain slaves to escape their masters, one group of 1960s psychologists argued that the crusade for equality would induce hallucinations and violent projections in Black men. Pharmaceutical companies hopped on board, with “drug advertisements in medical journals [portraying] maniacal Black men alongside promises of psychotropics’ calming effects. ‘Assaultive and belligerent?’ asked one such ad, showing a man with clenched fist and mouth wide open. ‘Cooperation begins with Haldol.’” The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Second Edition), or DSM-II, published in 1968, followed suit, pivoting from its long-standing position on schizophrenia as a passive, largely female disease to “the malady of the man who posed a threat to the social order.”

Ironically, Civil Rights leaders and writers of the period, from Martin Luther King Jr. and James Baldwin to Malcolm X, were also using the language of insanity to describe the Black experience in the United States. Malcolm X declared “insanity a sane response to racism,” while Baldwin observed that Black children ran “the risk of becoming schizophrenic” in public schools, where the touted ideals of liberty and justice for all so completely belied their own lived experience of apartheid America. A handful of “alternative” anti-racist and feminist psychoanalysts, social workers, and sociologists, including R. D. Laing, Frantz Fanon, Florence Rush, and Jules Henry, tended to agree.

Writing in 1967, Henry theorized that schizophrenic children learned to “sham,” or pretend, from their parents, who themselves accepted a world defined by sham principles. “It is clear that our civilization is a tissue of contradictions and lies,” Henry proclaimed, citing the Vietnam War and the deplorable state of Black people within a segregated society, and is thus “particularly adept at inducing both clinical and more generalized psychosis in its people.” Meanwhile, Rush, a social worker and activist, dedicated her career to challenging, as Farley writes, “the commonly held view that child abusers were psychologically deviant, positing that abusers were actually everyday men who wielded unchecked power over women and children in the off-limits domain of the family.” The NIHM researchers had frowned upon Sadie and Carl’s decision to circumcise their daughters, but tellingly never actually called it out as abuse. They merely noted that the culture of “pretending” ruled the family, and that the family’s efforts to “live up” to society’s expectations tied them up in painful knots. Yet the researchers were unable or unwilling to see that it was “society, not just the quadruplets’ family, [that] was troubled,” a society that “expressed racial anxieties as sexual ones, rendering many minds pornographic.”

Among the extraordinary historical threads running through Farley’s book is the tale of another Lansing family: that of Black Baptist minister Earl Little, his wife Louise, and their seven children. Their lives serve as a telling, schizophrenia-inducing counternarrative to those of the Morloks. Where the Morloks were given a home rent-free, at the taxpayers’ expense when the quadruplets were born, the Littles’ home was burnt to the ground by a local offshoot of the Klan; the perpetrators were never pursued or punished. Earl was killed soon after in a car accident under suspicious circumstances, dying in the same hospital where the quadruplets had been delivered. His widow Louise struggled to care for her seven children on a small welfare stipend; when she became pregnant by a man she was seeing, the state removed her children from the home and committed her to Kalamazoo State Mental Hospital, where she was diagnosed as an “agitator with delusions about white people” and spent 24 years incarcerated until her release in 1963. Her son would also, eventually, be unofficially diagnosed with “pre-psychotic paranoid schizophrenia” by the FBI. His name? Malcolm Little, better known to posterity as Malcolm X.

Rosenthal remarked upon the uncommon degree of “irrationality” and “immanent opposition” that marked everything the Morlok family said, did, thought, or felt. Yet he and his colleagues were never tempted to look outside the family for the sources of their internal contradictions. In the end, Farley uses the Genain sisters’ saga as a case study to argue that patriarchal Christian whiteness—then as now—is in and of itself a species of psychosocial pathology endemic to the United States. Carl’s preoccupation with “saving” his daughters’ white bodies from racialized public threats while himself perpetrating sexual domination over those same bodies in private is not a quirk of individual pathology; it is a long-standing national pastime.

Farley’s book thus adds to the increasingly urgent body of cultural critical work being done today on whiteness as an ideological construct that, like all ideology, works by declaring its own neutrality or invisibility. Her work resonates with sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom’s cultural essays in Thick (2019), as well as Jonathan Metzl’s pioneering work at the intersection of race, gender, and 20th-century psychiatry and medicine (and to whose books Farley frequently refers in Girls). In the essay “Dying to Be Competent,” McMillan Cottom narrates her own tragic interaction as a pregnant woman with the medical system and its assumptions about who counts as a “competent” economic and moral actor, her eventual outcome—a stillborn daughter—foreordained by the healthcare bureaucracy’s inability to acknowledge pain when it happens in Black bodies. “Like millions of women of color, especially black women,” she writes, “the healthcare machine could not imagine me as competent and so it neglected and ignored me until I was incompetent.”

In Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment is Killing America’s Heartland (2019), Metzl explores how, between 2013 and 2018, a spate of legislation in Missouri, Tennessee, and Kansas expanding gun access while cutting access to healthcare led to poorer health outcomes for the middle- to lower-income white supporters of these policies. Yet this was a price many were willing to pay for the Trumpian promise that white America would be made “great” again. Like Cottom, Metzl argues that the dream of whiteness ultimately functions to obscure brutal relationships of economic domination; the policies shore up the capital of a few dominant market actors “on the backs and organs of working-class people of all races and ethnicities, including white supporters.”

David Rosenthal derived the pseudonym Genain from the Greek gen- (“birth”) and -ain (“dire,” or “curse”). After reading Girls and Their Monsters, the reader understands that the Morlok sisters’ fates were dire indeed—just not for the reasons the white psychiatric establishment, at mid-century, was given every material incentive to believe. Ralph Ellison, whose 1952 novel Invisible Man remains among the best diagnostic portraits of Black invisibility and pathological whiteness to this day, might have foretold the Genain tragedy. “I am invisible,” his narrator claims, not due to any physical accident to his person but “because of a peculiar disposition of the eyes of those with whom I come in contact. A matter of the construction of their inner eyes.” Most days, he muses, “I remember that I am invisible and walk softly so as not to awaken the sleeping ones [for] there are few things in the world as dangerous as sleepwalkers.” With white nationalism on the rise in the United States, Girls and Their Monsters is a timely reminder of just how imperative this awakening is.

¤

LARB Contributor

Ellen Wayland-Smith is the author of two books of American cultural history, Oneida: From Free Love Utopia to the Well-Set Table (Picador, 2016) and The Angel in the Marketplace: Adwoman Jean Wade Rindlaub and the Selling of America (University of Chicago Press, 2020). Her essay collection, The Science of Last Things, is forthcoming from Milkweed Press in 2024. She is a professor (teaching) in the Writing Program at the University of Southern California.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Psychiatric Hubris

“Scientific Nightmare”: The Backstory of the “DSM”

Andrew Scull gives stellar marks to Allan Horwitz’s history of the DSMs.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!