I NEEDED A résumé boost, something to prove I could use my forthcoming English degree for more than record reviews and unpublishable short stories, so my Dickinson College career counselor handed me the number of a local man who was trying to get a charity off the ground. Something to do with drug recovery.

Two days later I was sitting in a strip-mall Panera across from ‘Ness,’ a former heroin addict with two half-missing fingers and a voice like barbed wire. ‘Ness’ had spent his entire life within a few miles of my school, and though he wasn’t yet 50, he looked a hard 65. For the last few years he’d taught an addiction-recovery course at the same jail where he’d served the majority of his seven prison sentences, and he now wanted to open a kind of born-again halfway house for his paroled graduates.

Anson House Ministries, as he’d registered with the IRS, was quite literally starting from nothing: ‘Ness’ spoke excitedly about a recent $200 private donation, which brought his total cash reserves to $212. His biggest accomplishment to date was attaining 501(c)3 status. From me, ‘Ness’ was hoping to get a cleanly written four- or five-page document explaining the concept of Anson House and the community’s particular need for its services. He handed me a tattered manila envelope filled with handwritten notes, decade-old newspaper clippings, and ten typo-riddled pages of his autobiography.

I didn’t have to read a word to know that ‘Ness’s mission was an important one for our mid-Pennsylvania town. Carlisle sits at the nexus of three Interstates — 81, 83, and 76 — thus attracting a heavy load of commercial trucking and its inevitable parasite, drug traffic. This was common knowledge on the campus, even though there was little meaningful interaction between the school and the troubled side of town, nicknamed “Carlem,” that supplied its maintenance staff and little else; whatever drugs we had came courtesy of someone’s brother or dealer back home. I worked in the cafeteria, though, which employed dozens of Cumberland County lifers, including a few high school potheads and some older folks who’d clearly done worse. Some of my friends worked for community-serving nonprofits in town, where they met a sample of the region’s catatonic and suspicious children. There was a resignation to the townies that could be harmless or venomous depending on the personality, and they all fit in to one of two camps: the people who drank too much or took too many drugs, and others who never did either. The former tended to be disfigured in some way, whether from a scar or an employment-deterring tattoo. ‘Ness’ was a rare specimen: a boundlessly optimistic representative from Carlisle’s embittered and self-abusing class. The fact that he was even reaching out to the college, when such an obvious and tense barrier existed between the neighborhoods, was endearing. I read his life story like it was a dispatch from a foreign country.

He’d spent much of high school getting blind drunk in frat houses, during a time when the school was a much more renowned party school than it is now. He’d found Jesus in jail while repeatedly serving time for possession, and he now proselytized God’s word with the intensity of a former addict. His nickname, omnipresent single quotes included, was an homage to a prison-time mentor.

In the middle of his typed notes for the current project, ‘Ness’ gave special prominence to an explanation of its name: Anson was the son, born in 1992 while he and his wife were still actively using, who died after only a few days of struggle in the hospital.

His mourning took a unique form: ‘Ness’ spent the mid-90s leading a campaign to get Paul McCartney knighted. He gathered thousands of signatures and sent them to the British government, attracting, he claimed, press attention from USA Today and Good Morning America. Naturally, people in the U.K. were curious why a rural Pennsylvanian was so concerned with McCartney’s recognition by the sovereign. He probably didn’t clarify the situation by appearing on a British morning show via satellite to answer questions about his efforts, stoned on heroin, having not slept for over 24 hours. He took McCartney’s eventual knighthood, in 1997, to be his own achievement. He met Sir Paul once, during an arranged meeting backstage after a concert in Philadelphia. They shook hands and quickly parted ways, and ‘Ness’ never got any formal recognition for his efforts.

There were a few stray local newspaper clips among his collection, little notices to the tune of “Area Man Campaigns for Beatle’s Knighthood,” but none of the national coverage he claimed had poured in. But his professional mission was so heartfelt, his vision so selfless and clear, that I assumed he was too noble to lie.

During our second meeting, ‘Ness’ seemed genuinely astounded that someone else had taken his project seriously. He was flying. The halfway house, he explained, was merely Step 1 in a larger dream to eventually establish a mini-city for central Pennsylvania’s recovering ex-con population and their spouses and children. He envisioned an apartment complex specially designed to cater to the needs of addiction-ravaged families.

‘Ness’ believed in fate and divine signs, and he couldn’t resist the cosmic irony that my college, which had hosted his first steps down a devastating road, was now granting him a sympathetic advocate for his utopian plan. When he learned that I grew up near Baltimore and was raised a diehard Orioles fan, his mind was fully blown. ‘Ness’ let forth a barrage of O’s trivia and recollections of Memorial Stadium, including many games with his now-estranged son. He asked me what I thought about the current management and rebuilding process – questions that had plagued the team for long enough that I could fake real insight, but I didn’t have the heart to tell him that I hadn’t watched a full game in years.

There were other details I kept from ‘Ness,’ like that fact that I had recently become a dad myself. My fiancée Justyna and daughter Nina were in Poland, my future wife’s home, and though I’d been there for the January birth only weeks earlier, it would be untold months until I’d see them again. In addition to a thesis, I was working nightly on visa applications and byzantine USCIS documents, trying to convince invisible bureaucrats that the two most important people in my life were worthy of entering the country. I spent hours each week trying to maintain a family through an undependable Skype connection. I spent many more hours wondering how I’d even begin to maintain it once we were finally reunited. The job search felt like a boot on my throat. That’s what pushed me into the career center in the first place, though I figured it would be unseemly to tell ‘Ness’ that his potential savior was motivated by pure terror and self-interest, just as it would have been inappropriate to let this narrowly recovered addict know that I went back to my apartment every night and smoked as much pot as it took to forget that everyone around me seemed to be having fun.

I was filled with resentment, primarily for my own tough situation but also for the sheltered, carefree lives of my classmates, who I found simultaneously pathetic and enviable. So when ‘Ness’ asked me to attend the Anson House board’s monthly meetings at Cumberland County Prison, I could hardly turn down the opportunity to work with real people and their real problems.

Once a month I traded my typical routine — a sour grimace, a piercing fear of the future, an angry fist pointed at the heavens — and borrowed someone’s car to drive off campus. I felt a swell of pride as the downtown historical district gave way to the gray, turnpike-exit sprawl. Charming, multicolored porches turned to stained clapboard siding. Bistros and bakeries became liquor stores, then nondescript sandwich shops, then fast food. I drove past the local surf-n-turf palace with a marquee daring people to eat a 32 oz. sirloin for the chance to win a truck, stopping for stale coffee at a corner gas station.

‘Ness’ introduced me to the board with pride, adding, “He’s from Dickinson” as if I held sway over the college’s checkbook. The other members – a local car salesman, an intake coordinator from a nearby rehab center, a Carlisle lawyer -- nodded and tried to get the meeting started. It began with a prayer. ‘Ness’ thanked God for bringing everyone together, and asked that he show the right way for the group to do His work. “Thank you for bringing John to us,” he added, then gave an amen.

It was a painful dynamic in that windowless cinderblock room: a half-dozen people trying to do real yeoman’s work for their community, led by a man who had absolutely no managerial wherewithal whatsoever. Leslie, the secretary, took notes in big looping handwriting, at one point simply scribbling “WE NEED MONEY” and underlining it twice. Everyone promised to make good on his or her various personal and professional contacts, and ‘Ness’ closed with another prayer.

He and I ended up chatting in the prison parking lot after the meeting, mostly about the Orioles but also about ‘Ness’s frustrations and memories. I didn’t have much response to either topic, but I enjoyed hearing about his father, his impending grandchild, and his death-defying nights in between jail terms. Like most colleges, my school cultivated and thrived on a widespread sense that every student was primed for imminent greatness, and within that scene I often felt like the guy who’d already forfeited his potential in order to become an early father. It was a relief and a pleasure to hear someone else’s stories of life run amok and families culled together from circumstance and surprise. It didn’t matter that ‘Ness’s’ own life was clearly a species of disaster. All I needed from him was the regular boost of confidence I got from seeing that life goes on, and that meaning can be wrested from the wreckage.

This sequence repeated itself for the next three months. We’d gather, discuss the need for money and our difficulty in finding it, lament the absence of whichever board members weren’t able to come, mention possible changes to the organization’s administrative structure, and put off a group vote on those changes until enough people were present to meet the quorum. Each meeting was audio recorded and the minutes were taken diligently. I had no voting power and little to offer besides a general interest in the project and a positive attitude, but the board seemed to tolerate my presence in the same spirit that they tolerated ‘Ness’s other quirks, like his inability to get to the point of a thought or his regular frustrated outbursts.

Around this time ‘Ness’ called me to explain that the board was angry with him for using Anson House funds to repair his personal computer. He said that, since they lacked a proper office, the repairs constituted a business expense, then he fumed about the board and its lack of progress. ‘Ness’ told me not to worry if everyone seemed hostile at the next meeting; he had a line on a property and things looked like they were just starting to move in the right direction. If the board needed to break up and start from scratch, then that was God’s will.

There were three board members missing at the next meeting, which gave ‘Ness’ a reasonable defense that nobody took the organization seriously except him. Nothing was decided, no votes cast for anything, and no decisions were made. In a huff and a prayer, the meeting was adjourned.

‘Ness’ and I had our usual parking lot one-on-one immediately afterward. Worrying that it wasn’t yet adequately clear, I explained once again that I knew nothing about buying a house or communicating with the government or helping people get sober, though I still withheld the fact that most of my waking thoughts involved my inability to do precisely those things for myself. ‘Ness’ continued to take my benefit to the organization as a given. The board, he’d decided, would have to be dissolved and replaced with people who understood the need and scope of his mission. He asked if I had anyone in mind, perhaps someone from the college, and I said I’d go back to the faith-based and community-service campus clubs that had already politely declined my requests for volunteers and donations.

Standing under an early spring sky, hearing this man hold forth on the will of God in the parking lot of a county prison, I finally admitted to myself that this whole experience made no sense. In small part, I did believe that an organization like Anson House would be a great help to the town, even if it seemed increasingly unlikely that Anson House itself was going to be that help. I also figured it might be impressive in job interviews to talk about helping a charity, though I wasn’t sure what kind of employer would be impressed by my new reference — a hoarse, seemingly disoriented man with ideals to spare but barely more than a minor embezzlement fiasco to show for them. I clung tight to the notion that my nights in the prison were somehow closer to mature, adult experience than any I could find on campus, and yet there I was, the confidante and would-be meal ticket for a guy whose opinion of me rested on an afternoon’s work and a coincidence of sports fandom.

At ‘Ness’s’ request, I wrote a letter to McCartney Productions Limited, enclosing photocopies of the Carlisle articles about his ‘90’s campaign and a cover letter asking if Sir Paul might be interested in contributing to Anson House Ministries, the latest project by the man who helped get him knighted. I never received a response.

My personal obligations began to overwhelm any interest in Anson House as graduation approached, and unlike ‘Ness,’ I was building a little positive momentum. I managed to find a job outside Baltimore writing marketing materials for an education company. I finished my thesis and managed to secure Justyna’s visa, and in mid-May I went to Poland to help her move permanently to America with Nina. Within 30 days, I was to get married, find and move into an apartment, buy a car, and start my first job.

That first month passed in a blur, but soon we were living some version of the life I’d been pining for. Our apartment was a cozy third-floor walk-up at the bottom of a treeless hilly street in north Baltimore, and its rickety rear balcony offered an oddly soothing view of I-83, which ran close enough to cast a shadow on our building’s closest curb at midday. I had friends in the neighborhood, many I’d known for years, and was thrilled to be outside of a campus and living around people whose conception of life and success extended beyond a semester schedule or a grad-school application deadline.

But the adrenaline of those first massive changes subsided quickly, and I ran face-first into the discovery of my own inconsequentiality that awaits all recent graduates. A good part of my “writing” job involved printing out hundreds of informational packets with the office’s car-sized photocopier; in my spare moments I line-edited the company’s homeschooling curriculum course catalogue, charged with adding a little youthful verve to descriptions of elementary-age subject bundles. I was comically ill-suited for adding “verve” to anything: every morning and afternoon I rode the Light Rail into Baltimore County and back, leaving my wife alone in a strange and unfriendly city with a stroller she had to carry down three flights to use. Sometimes on those long, perennially unpunctual commutes I’d lose interest in my book or fall prey to parental fatigue, and a grim realization would seize hold: I’d spent a full year cursing my lack of adequately adult surroundings, only to find that the typical adult work day left barely any room for a sense of effectuality, let alone accomplishment.

And then ‘Ness’ called. I’d never been so happy to hear his blown-out voice or his baseless optimism for the Orioles’ latest disastrous season. He was in fact calling to see if I would join him for his annual sojourn to Oriole Park, and I agreed happily. Then he asked if I’d be willing to join the Anson House board of directors as a voting member. It would require a monthly three- or four-hour round trip ride to Carlisle for a 60-minute meeting — and almost certainly a frustrating, unsuccessful one at that. I said yes immediately.

The group was no longer meeting in the prison, but in the office of another lawyer who’d joined the board. There were a handful of new faces and a lot of new excitement, and once again ‘Ness’ was this close to closing a deal on a property he’d been offered at a discount since the realtor supported the cause. I took my seat, gas station coffee in hand for old times’ sake, and offered to consult my philanthropic Baltimore connections, of which there were none. Once again, ‘Ness’ introduced me to the new people as if the benefit of my involvement spoke for itself.

I was intent, like never before, on repaying his misguided faith in me. It was a thrill to have something to think about other than Justyna’s gnawing depression and the relentlessly uninteresting job I worked to support our tenuous new life together. I called my parents’ nonprofit-sector colleagues, and took notes during long phone conversations about fundraising and corporate presentations. I sent emails to Baltimore journalists, telling them about my exciting new venture just 70 miles up the interstate. And once a month I traveled those 70 miles after work, arriving invariably 15 minutes late to an hour-long meeting that accomplished nothing. Then it was 10 or so minutes of small talk with ‘Ness’ and 70 miles home again, begging under my breath that there would be no nighttime roadwork.

¤

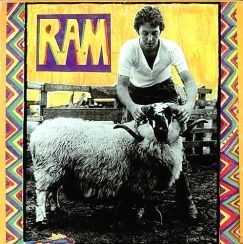

I decided to use these rides as opportunities to brush up on Paul McCartney’s solo records, feeling I somehow owed that much to ‘Ness.’ The first album I tried was Ram, the lone album credited to both Paul and Linda McCartney, released in 1971.

Ram has 12 songs, few of which contain more than five or six lines and none of which even hint at emotional complexity. There’s a typical McCartney character sketch, “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey,” where he adopts the stuffy upper-class twit accent that any Beatles fan knows well. There’s some antic white-boy blues, some vaguely socially aware gesturing, plenty of gooey love lyrics, and more indelible melodies than many artists write in a decade. This is primo comfort-zone McCartney, in other words, recorded almost entirely by himself, at home, between the births of his first and second daughters, and right after leaving the biggest musical act in human history. He was not yet 30 when it came out.

The record ends with one of its longer, familiarly Paulish song-suites, “Back Seat of My Car,” in which a boy and girl steal away from their families and head for Mexico City. Her father’s voice trails them wherever they go, warning ominously that they shouldn’t have sex. The track ends with Paul and Linda shouting a mantra-like chorus — “We believe that we can’t be wrong” — as the orchestration swells under a triumphant guitar solo and McCartney’s ooga-booga “Hey Jude”-style vocals.

A loopy ukulele sing-along, “Ram On” appears in different versions on either side of the LP. It has only the slightest wisp of lyrics, playing off McCartney’s nickname in the Beatles, Ramon:

Ram on, give your heart to somebody

Soon, right away.

Moments of regret and anger surface throughout Ram, but McCartney washes them away immediately to make room for more melodies, more whimsy, more Linda. It is literally a record of one father’s addiction to the recording studio and his family. It’s obsessive, but without any of obsession’s darkness; it’s all joyous highs. I’d spent a year or more convinced that early fatherhood was somehow getting in the way of my intended life, but Ram’s optimism scrubbed away my self-pity. The song “Dear Boy,” with its admonishing lyrics and wall of bouncing harmonies, felt like it was being broadcast directly to me:

I guess you never saw,

Dear boy, that love was there,

And maybe when you look too hard,

Dear boy, you never do become aware.

I guess you never did become aware, dear boy.

Twice the word “lucky” appears in Ram: in “Too Many People” to chastise those “looking for a lucky break,” and in “Long-Haired Lady” to brag, “I’m the lucky man she will hypnotize.” I was dead guilty of the former and desperately needed to hear the latter. I stopped looking too hard for ways to fight against the reality of my early fatherhood and instead allowed myself to be hypnotized and delighted by Nina’s emerging personality. I came to sympathize with both the young man who runs away with his girl and the poor father who just wants his daughter to come home. More than that, I became convinced that the song was a distillation of every conflicting urge that parents constantly feel.

Ram’s songs began forcing themselves into my life, popping into my head as I gave Nina a bath or watched a movie with Justyna after putting the baby to bed. Before long, the unthinkable happened: my own family grew comfortable. I left my job for a better opportunity. The little one took her first steps and spoke at last. We found a nicer apartment, on the first floor in a more centralized block. Most incredibly, we stayed in love. In the face of Justyna’s homesickness and our mutually routine existential crises, she and I still managed to collapse into bed most nights with our feelings and our admiration intact. We cultivated the little family customs that seemed impossible only months before, and somehow managed to keep laughing in the face of mounting bills and life’s uncertainty. And I began to appreciate that this too was adulthood.

I called ‘Ness’ and explained that with my new job, the trips to Carlisle just didn’t make any sense for me anymore. I told him that my interest in Anson House hadn’t waned, and that I’d continue whatever work I could from Baltimore. He accepted my resignation from the board as another divine tell, and announced that it was time for a permanent restructuring. We ended the conversation amicably, and when I hung up I thought of the various stories ‘Ness’ had arranged in his mind — the small-town boy who survived seven prison stays, the lower-class castoff who kicked heroin and wanted to be a savior, the superfan who crusaded for a musician’s knighthood. The through-line was ‘Ness’s pathological aversion to pessimism. He simply could not believe that any setback or improbability could derail him for good. Anson House would open, lives would be saved, the Orioles would return to the mid-‘60s glory. It was all foreordained. And for his hero he chose — who else? — the cute Beatle, the author of “Silly Love Songs” and “Maybe I’m Amazed.”

During that conversation, I asked ‘Ness’ his opinion of Ram, thinking perhaps we’d at last found an honest mutual obsession. But he said he’d never liked that record as much as Band on the Run or Tug of War or Wings Across America — albums that feature McCartney in eager-to-please mode, not his self-contained, quiet-farmhouse phase. For ‘Ness,’ optimism meant reaching out to other people. It meant leading a sing-along and starting a new band. But I was too raw-nerved for all that; I needed something that would help me appreciate the beauty around my dinner table.

A long period of silence passed between us, and when the phone call came, months later, I realized that I’d been waiting for it all along. It was his wife, informing me that ‘Ness’ had died during a hospital stay for a staph infection. The funeral was the next day, the same time as an essential meeting for the startup I’d joined. She told me that I meant a lot to him, and that my enthusiasm for Anson House was a source of great pride and inspiration during all his recent setbacks. He was just talking about me the other day, in fact.

When I hear Ram now it’s more like a sense-memory than an album. I hear McCartney’s infectious glee, see the pictures of him unshaven and holding his baby girl, a living reminder that family and domesticity are their own rewards. It’s the lasting legacy of a relationship that entered my life like a hurricane before disappearing like vapor. ‘Ness’ took my morbid curiosity as a reason to believe, and I found his belief so inspiring that I used it as an anchor when my own life felt lost at sea. For all I know he never gave these words a second thought, but they remind me of him still — they could have been his mantra and I adopted them as mine: Give your heart to somebody. Believe that you can’t be wrong.

Recommended Reads:

"The Girl with the Father Tattoo": Michele Pridmore-Brown on Our Fathers, Ourselves by Peggy Drexler

LARB Contributor

John Lingan’s writing has appeared in The Morning News, The Point, 7Stops, The Quarterly Conversation, and many other venues. He’s working on a memoir about becoming a father during college.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Survive: Alice Bag's "Violence Girl"

Beyond the image of Bag’s punk persona, the memoir’s title also alludes to the specter of violence that shadowed her home and childhood.

The Girl with the Father Tattoo

And so it was that daughters, perhaps more relationally adept on average, became the more fertile conduit for paternal ambition.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!