Sinking Cities

A lyrical new book on disappearing shorelines connects science to the personal.

By Rafaela BassiliJune 12, 2018

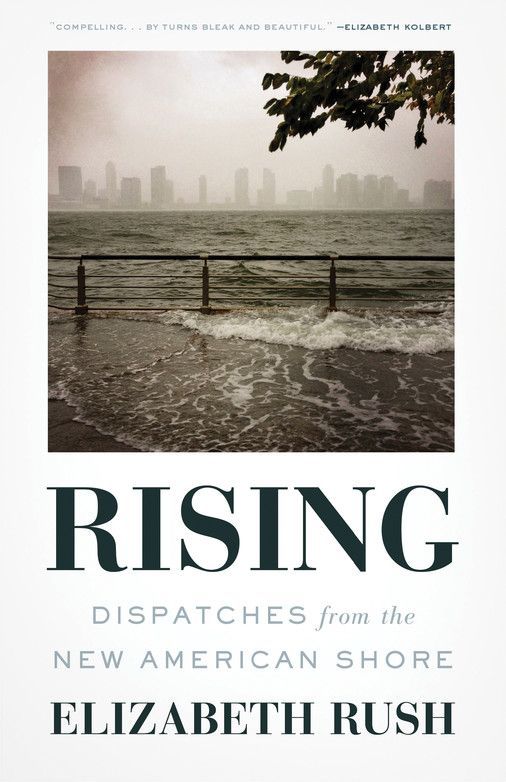

Rising by Elizabeth Rush. Milkweed Editions. 320 pages.

THE SEPARATION OF ART from science — largely at the hands of scientists themselves to preserve their rigor — has created a dangerous by-product: a distance from the environmental dangers and threats that paint our landscape. In her lyrical and fact-packed investigative effort, Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore, Elizabeth Rush successfully attempts to bridge the gap between the scientific and a terrifying aesthetic by studying the effects of sea level rise on seaside communities and marginalized groups of people.

Divided into three sections, the book follows Rush’s five-year journalistic trek through those parts of the country, from Rhode Island to California, that are most vulnerable to sea level rise, offering profiles of scientists and local members of the communities she visits. With tasteful and dynamic didactic language, she informs the layperson about the imminent threat of climate change while grounding the massive scope of the problem on heartfelt human and interspecies connection.

It is easy for the regular fiction reader to avoid nonfiction work dealing in science — perhaps out of a sense of intimidation, or a fear that it will be boring. This reluctance serves a purpose in keeping that space between the scientific and the artistic alive and well. It also preserves a vague understanding that climate change is advancing while keeping our own agency at arm’s length. What can recycling a few plastic bottles do, after all, to reverse centuries of heavy industrial damage? Rush argues that we can create a much more meaningful conversation in which we see ourselves as part of the land — in which we acknowledge that we exist with the land we occupy as one.

While she explores the coast of Rhode Island in the opening sections, the author warns us of the importance of connecting language to science: “I believe that language can lessen the distance between humans and the world of which we are a part; I believe that it can foster interspecies intimacy and, as a result, care.” This tone-setting idea, which will accompany all of her accounts, presents language as a bridge between the scientific and the metaphysical. For example, she opens the book with a meditation on how heritage and culture can be uplifted through the utterance of species names, especially those that are both endangered and connected with forgotten, erased histories. Such is the case with the plant tupelo, whose name is inherited from the Creek language: “[S]aying tupelo takes me one step closer to recognizing these trees as kin and endowing their flesh with the same inalienable rights we humans hold.”

Rush waits to assess the progressive works of heavily funded organizations until the book’s last essay, “Looking Backward and Forward in Time,” in which she reports on the efforts to restore tidal salt marshes in the San Francisco Bay. Even then, she doesn’t shy away from questioning human intervention tactics: “Do you ever fear that you’re playing God?” she asks John Bourgeois, the executive project manager of the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project. Bourgeois dodges the question, and Rush takes note.

Climate change literature is notoriously dry and pessimistic. Rush does her best to avoid these pitfalls by weaving data into personal tales that don’t shy away from doubts. When dealing with a subject that implies impending doom, she is earnest in telling the reader the ways in which her expertise can take a gloomy toll on her own experience with research. This honest vulnerability is Rush’s best narrative approach, and it informs the way she deals with one of the most uncomfortable political conversations surrounding climate change: economic privilege.

Throughout all accounts, she makes clear her desire to spotlight communities and groups most vulnerable to the effects of sea level rise. She alternates chapters of her investigative work with sections composed of long, uninterrupted monologues by some of the people she has encountered in her process. A woman named Nicole Montalto lost her father to Hurricane Sandy. Chris Brunet had to relocate from his land in Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana. Rush lets them both speak for themselves, instead of intervening — like humans do with nature — and interpreting them as her own.

With a capacity for self-reflection, Rush isn’t scared of analyzing her own privilege as a white, educated woman, a gesture shown by her conversation with Alvin Turner, a man living in Pensacola Beach, Florida, whose appearance initially strikes Rush as frightening. Recognizing the privilege and learned bias that lead her to perceive his dark complexion and impoverishment as scary, she shows the reader how self-awareness is the basis of empathy and compassion.

The author’s largely successful lyrical approach to environmental writing is complemented by the structure of her storytelling. Within chapters and throughout the string that keeps her stories connected, Rush jumps back and forth in time, theme, and tales, deftly creating movement between thoughts that challenge the all-too-common dryness of scientific journalism.

The world isn’t only the physical universe of objects outside the body; it also hums within the mind, is the constellation of thoughts we have about tangible matter. Destruction lingers, takes place many times over — once in the moment of violent dissolution and also much earlier, when we learn to think of this derangement as possible. When we learn to acknowledge that the water will come. Then just imagining an end to the world as we know it means also, at least partially, losing your own mind.

Rush’s effort to make scientific journalism digestible is also at times bogged down by esoteric language that might inadvertently distance the reader whose vocabulary doesn’t include names of various botanic and animal species. The layperson might find themselves turning to a dictionary or a Google search when faced with paragraphs heavily packed with species names. It seems important that this engagement occurs, as the author places such emphasis on connecting words and names to feelings and care. By pairing species names with vivid descriptions of landscapes that help paint the picture essential to humanizing the people she encounters, Rush makes her writing part of the reader’s journey to actively seek out the unfamiliar.

During a time when perceptions of reality have been distorted so that even those fields of study that we have, for years, trusted as empirical and incontestable have become part of the political conversation, a book like Rising connects science to the personal. Arguing that it is on us — communities, people, and those who occupy positions of privilege — to relocate and adapt to a changing climate together, Rush minimizes the distance humanity has created from the planet that has been laboring to house us for so long.

¤

Rafaela Bassili, a native of Brazil, is a writer living in Orange, California.

LARB Contributor

Rafaela Bassili, a native of Brazil, is a writer living in Orange, California.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Art and Activism of the Anthropocene, Part I: A Conversation with William T. Vollmann, Chantal Bilodeau, and David Wallace-Wells

Amy Brady of "Guernica" magazine presents the first conversation in the series “The Art and Activism of the Anthropocene.”

Here’s to Unsuicide: An Interview with Richard Powers

"We came into being by the grace of trees." Everett Hamner talks with Richard Powers about his latest novel, "The Overstory."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!