Sifting the Ashes of Malibu

On the first anniversary of the Woolsey Fire that leveled parts of Malibu, a new book tells the victims’ stories.

By Avery SilverbergJanuary 9, 2020

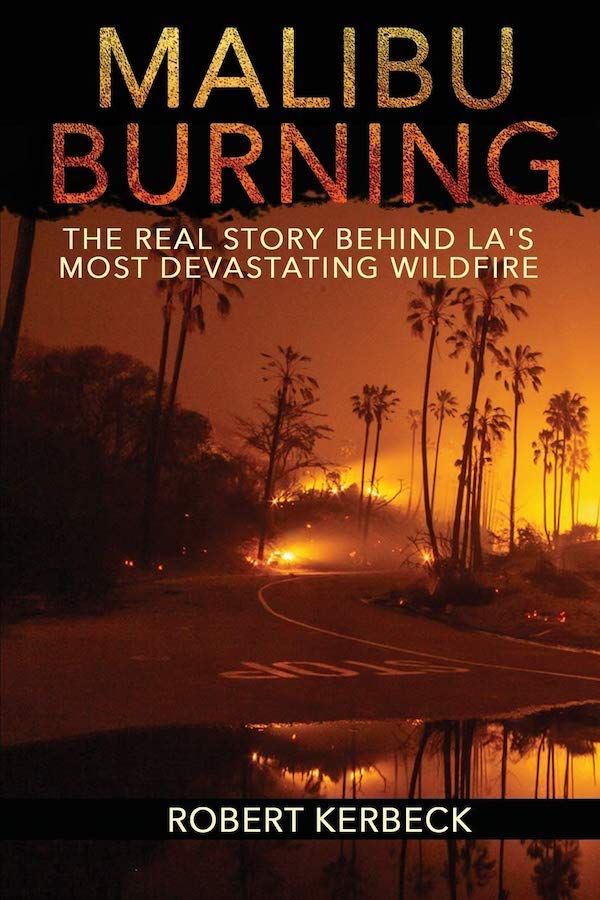

Malibu Burning by Robert Kerbeck. MWC Press. 262 pages.

FEW PEOPLE LIVING in the Los Angeles metro area will forget what the air looked like when a wildfire leveled part of Malibu in November 2018. I remember not being able to leave my house without coughing, the ashes falling on my car like snowflakes. I remember feeling like I could not breathe, could not see.

One year after the fires, a new nonfiction account from Robert Kerbeck, Malibu Burning: The Real Story Behind LA's Most Devastating Wildfire, sheds light on what it was really like to live in the midst of the conflagration. The first sentence is a grabber, introducing the personal tone deployed throughout the book: “Few things will forever change you like the terror of thinking you’re about to be burned alive in front of your kid.”

Most of the population hasn’t encountered an experience as traumatic as the Malibu fire, but many do know what it’s like to be a parent, or to look up to one. Immediately we are able to feel what Kerbeck feels, raising the question: what would I do if I were him?

One of the most important aspects of Kerbeck’s work includes his ability to document the extent that working-class families were affected. “They are not, for the most part, rich or famous,” he writes. “There is a whole social structure in Malibu that most outsiders don’t even know exists.” Kerbeck is right: most outsiders hear distantly about Malibu and correlate it with glamour. The fire affected so much more than just celebrities with million-dollar mansions, but the teachers, gardeners, farmers, and children, too. He doesn’t leave out celebrities entirely, shedding light on the way Julia Roberts, Bob Dylan, Nick Nolte, and others were affected. The famous do not receive a VIP press badge to avoid damage — none of us are safe from what fire can burn.

Aside from the necessary statistics and historical accounts of the Malibu terrain, Kerbeck’s prose feels like fiction. Each chapter introduces a separate subject’s account of the fire, gauging their personal reactions, emotions, and aftermath of the destruction. The chapters all begin the same way, introducing a new “character” to the story. A restaurant owner, passed down from father to son, fighting flames to preserve the treasured building. A high school senior, navigating the difficulty of college decisions and SAT exams, watched as her only home burned to the ground. Once the structure is understood, the reader reacts like a driver watching an accident on the freeway. You just can’t look away.

“Many of their neighbors might have died if Danielle hadn’t been up with two newborn babies,” Kerbeck writes, as he describes a woman who acted fast because she happened to be awake in the middle of the night. I was pulled in by the characterization of each subject, entranced by their dialogue and vulnerability — and I wanted it to stay that way. Kerbeck’s transcription of each interview is so visceral, his words make readers wish the account of suffering was as fictitious as it felt. But this is, alas, the real terror of a real event. The moments when he breaks up the subject’s monologues to add his own observations come as unwelcome interjections.

I worried Kerbeck would fall into the writer’s trap of glorifying the natural disaster, treating it as something beautiful. In some moments, he recounts residents’ quotes of looking over the hills of Malibu, and seeing the beauty behind flames rolling up and down the mountains like ocean waves. But Kerbeck avoids drowning in this motif with countering displays of human strength. While he describes the horror of realizing everything you have has been burned, he also uplifts the reader by sharing moments of individual resilience. “It was exhausting work, physically and emotionally, going through the charred remains of your home hoping to find that one thing that hadn’t been destroyed,” Kerbeck writes, retelling an anecdote of a Malibu elementary school teacher, who finds a children’s book amid ashes. “The page gave Nicole a sense of hope in the midst of so much loss.”

One lasting mini-scandal of the Woolsey Fire is how few firefighters were involved, and how many more civilians were doing that work for them. “You gotta write about what happened,” a fellow surfer tells Kerbeck. “How things got so screwed up that your wife and son were doing the work firefighters should’ve been doing.” This sentiment is at the heart of the book. In each survivor’s anecdote, their stories surround their heroism; civilians save their own homes, their neighbors’ homes, their own pets and family members. Meanwhile, firefighters were nearby, not moving quickly enough. Kerbeck offers both sides to the controversy, including insight into Deputy Fire Chief Vince Pena’s point of view. The fascinating interview sheds light onto why not enough firefighters were involved — including the fact that the Santa Monica police department did not come to Malibu’s aid. While Kerbeck has a clear stance on the matter, I appreciate the fact that he gives a range of perspectives to the situation. I admire that not all of his questions are answered; the best nonfiction leaves readers to think for themselves.

It is evident Kerbeck is a natural journalist, in the way he collects stories, both of horror and camaraderie, from the old, young, and middle-aged. Differences do not apply when devastation strikes, and people want to read about people of all backgrounds. Stories are our way of engaging with the world around us, and the way we live. In this case, Kerbeck’s book allows readers to study human nature, as well as the way we would respond to disaster in case we needed to face it.

Malibu Burning reminds us how important connection and communication is when nature dominates man. Humanity sticks together, and the proof remains in these words. This book is less about the fire and more about the people who were affected by it.

We have taught ourselves to hashtag and move on. From natural disasters to school shootings to presidential elections, we fight, and we forget — over and over again. The news stopped covering this event long ago; they have moved on to more recent wildfires. Just one month ago, driving along the 405, I watched as helicopters dropped bright red chemical retardant along the hills of the Getty in the hopes of slowing down the fire’s movement. Kerbeck’s book makes me wonder: Who will tell this story? Who will report back on the thousands of lives affected by flames this year? What about next year? Words can’t fight natural disasters, but they can allow us to look at them differently. Last year, I saw the fire as nothing more than nature, destroying what we can’t control. Now, I see the people. I see individual lives, not numbers.

¤

LARB Contributor

Avery Silverberg is a recent graduate from Chapman University, holding a BFA in creative writing. She works as an assistant at the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, and is an avid reader of literary fiction, young adult fiction, and memoir.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Lessons From a Sequoia Grove

The Fire Files

Claire McEachern writes about escaping the Malibu fires

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!