Self-Curation: On Rachel Mannheimer’s “Earth Room”

C. Francis Fisher considers “Earth Room,” the debut collection of poems by Rachel Mannheimer.

By C. Francis FisherJune 10, 2022

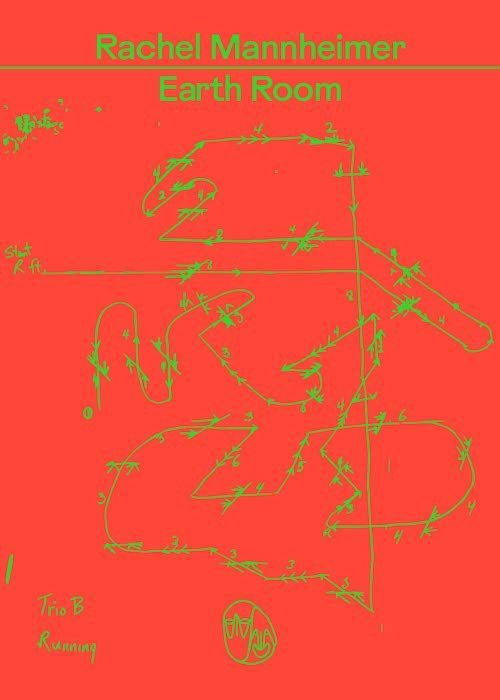

Earth Room by Rachel Mannheimer. Changes. 100 pages.

THE SECOND FLOOR of a loft on Wooster Street contains the New York Earth Room. Executed by Walter De Maria in 1977, the artwork is described as an interior earth sculpture and features 280,000 pounds of dirt. The day I went, it was sunny, and light poured into the loft, electrifying the contrast between all-white walls and the mass of deep brown soil on the floor. The smell was delicious, like a park after mulching. On my way in, the attendant told me I was lucky to see the room this way, whereas normally he rakes the dirt vertically, today he raked horizontally.

In Rachel Mannheimer’s debut poetry collection, Earth Room, the speaker recounts a similar experience with the sculpture:

Bill cares for the dirt —

raking and watering, removing sprout and fungi that

might grow. I used to only rake in one direction. Now, I

also rake horizontally.

Mannheimer is at her best when she writes about art. For those who have seen the works she addresses, there is the special thrill of recognition, like mine upon having a similar experience with Walter De Maria’s New York Earth Room. For those who haven’t, she provides enough contextual information that they can still engage. By situating the art historically and connecting the work to her personal life, she makes accessible what sometimes seems rarefied, conceptual, and performance-based. In “New York,” there seems to be an identification between Bill and the speaker, emphasized by the italicized quotation marks so that a small slippage occurs between the “I” of the speaker and Bill’s “I.” This identification builds upon the care each shows toward the artwork — Bill through his daily maintenance, and Mannheimer through her poems.

Later in the poem, we learn that the first Earth Room appeared at the Galerie Heiner Friedrich in Munich in September 1968: “It was installed for less than two weeks. Or, if you ask / Heiner, it’s still there.” Mannheimer’s interest in art that is particularly transitory, such as performance-based and conceptual work, takes on an elegiac quality. What happens to the Earth Room that no longer exists? Does it cease to exist or continue living in the minds of those who saw it, in the artistic discourse? These questions recur throughout the collection when Mannheimer turns her gaze toward familial loss and grief.

Mannheimer’s collection is, among other things, an elegy — dedicated to and for her mother. We learn of the mother’s death indirectly. In “Providence,” the speaker describes meeting Chris, the man with whom she will come to navigate the solitude and companionship of an artistic relationship. In this poem, the speaker “cried when he asked / about my mom.” Later in “Berlin,” a poem that addresses the depictions of mothers in a museum’s collection, the heartrending final couplet reads, “Why should I ever miss her less? / It’s only ever longer since I’ve seen her.”

In these moments, the speaker’s reaction to the loss of the mother is somewhat peripheral. The maternal figure haunts the book without taking center stage because the speaker only ever alludes to her grief as opposed to addressing her mother’s death directly. In this way, the loss is relegated to the background, as is the emotional current.

There is an inherent danger in exploring grief. We risk becoming the point of focus rather than the person who was lost. Jewish rituals of mourning such as covering mirrors avoid this self-referential method of grieving. Mannheimer’s book performs a similar feat by evoking the mother as a haunting rather than constantly returning to the speaker’s own experience of loss. By performing this self-effacement, the poet maintains the singularity of the lost beloved rather than turning the attention to herself. The collection also acts as a testament to life, like a letter recounting experiences the poet wants to share with the lost mother that says: Here is what I have been thinking and seeing, I love you, I’m still living.

Elsewhere in the collection, Mannheimer continues to displace herself. Despite the fact that the poems are always in the first person and often quite personal, she maintains a strange sense of distance through her references to artwork, history, and philosophy. At times, the tone becomes so detached that it verges on journalistic. For example, in one of several poems titled “New York,” she writes,

Smithson quotes Olmsted, regarding Central Park:

The museum is not a part of the park, but a deduction from it.

the subways, though, do not deduct —

they, like parks, allow escape.

Here, Mannheimer achieves this effect through a quotation whose tone is academic rather than conventionally poetic. In this manner, the poet allows the reader to make up their own mind as opposed to manipulating or directing the reader’s emotions. For example, someone might disagree vehemently with Olmsted, citing the possibility of escape inherent in a trip to the Met. The poet almost removes herself from meaning-making and acts more as a ventriloquist who puts the reader in conversation with others. Clearly, this curation is still done by the poet herself, but the effect is such that the reader almost forgets the presence of the poet.

In other poems, a similar tone allows the poet to present politically salient commentary without falling into finger-wagging. While much of the collection explores Jewishness, two poems in particular address issues of the Israeli state. “Anchorage” is a short poem reproduced below:

The story I took

from Sunday school was this:

God created the world, God parted the Red Sea,

and after the Holocaust, the British had some land no one was using

so they gave it to the Jews as a home.

This poem’s relationship to subjectivity is foregrounded through the use of the term “story,” which is generally understood as fictional as opposed to factual. In juxtaposing the surrealism of creating the world and parting the Red Sea with the establishment of the state of Israel, the speaker points to the cruel absurdity of Palestinian displacement and settler colonialism. Mannheimer’s political views are always expressed this way — with a subtlety that makes the reader think it might have been their own opinion all along.

The power of the collection also exists in the ways that the poems respond to one another. “Anchorage” takes on an even more pressing valence when “Washington D.C.” comes after, a poem that reprises the history of imagining Alaska as a land for Jewish refugees from Europe. The final couplet reads: “Who, Hitler asked, remembers the Red Indians? / He meant this inspirationally.” The horror of this moment is underlined by the stark lack of commentary.

In a world that is caught between an obsession with the individual and an intellectual or political discourse that attempts objectivity, Mannheimer offers us a third option: the self as tantamount to our understanding of reality and yet rooted in the world that shapes it. The poet’s vision of selfhood is one that is fashioned in reaction to art, friends, politics, and family, and is constantly pointing outward to the realities of our shared existence.

The obsession with the individual is a capitalist one — today, the individual is understood as a consumer primed for spending. Artwork is not safe from the commercialization of our world. In her foreword, Louise Glück, who selected Mannheimer’s manuscript as the winner of the first annual Bergman Prize, writes, “Mannheimer’s subject is art. Not the art that endures unchanging in museums and libraries but the transient art of performance and installation, the mutable, perishable forms.” I think it important to add that these are the forms of art that even today are impossible to own. One cannot buy a particular performance of Yvonne Rainer’s “Trio B: Running” or Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. There is something resistant in Mannheimer’s interest in these types of art, something radical.

In this way, Earth Room asks large questions in an understated voice — how to grieve and how to love, how to be a family and how to understand place. For answers, she turns to art, questioning the lines we draw between performance and life. Does the speaker give us definite answers? Certainly not — we must come to them ourselves, but she’s here alongside, encouraging, reminding us in the final poem that we are “very very very very / very very close.”

¤

LARB Contributor

C. Francis Fisher’s writings have appeared or are forthcoming in PANK Magazine, Pacifica Literary Review, Los Angeles Review of Books, Asymptote, and elsewhere. Her poem “Self-Portrait at 25” won the 2021 Academy of American Poets Poetry Prize at Columbia University. She lives in Brooklyn, New York, where she works as the poetry editor for Columbia Journal.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“Shouldn’t Life Resolve?”: On Ange Mlinko’s “Venice”

Oona Holahan journeys through “Venice,” the latest collection of poems by Ange Mlinko.

Putting Things Back Together: On Alexis Sears’s “Out of Order”

Maryann Corbett is awed by “Out of Order,” Donald Justice Poetry Prize–winning collection by Alexis Sears.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!