Second Acts: A Second Look at Second Books of Poetry by Linda Gregerson and Rachel Richardson

Lisa Russ Spaar on "The Woman Who Died in Her Sleep" and "Hundred-Year Wave".

By Lisa Russ SpaarAugust 27, 2016

Hundred-Year Wave by Rachel Richardson. Carnegie Mellon. 80 pages.

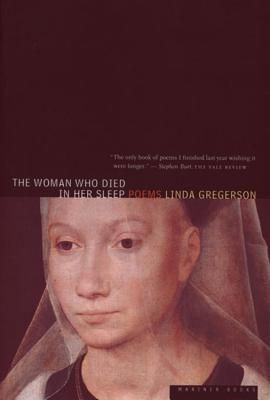

The Woman Who Died in Her Sleep by Linda Gregerson. Mariner Books. 96 pages.

The recent publication of Linda Gregerson’s Prodigal: New and Selected Poems: 1976–2014 (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015) afforded this longtime fan of Gregerson’s perspicacious, sumptuous, intellectually agile, and unflinching poetry the privilege of revisiting selections from her five previous collections as well as discovering 10 new poems. I was especially gratified to experience anew the extraordinary formal force and originality of Gregerson’s second book, The Woman Who Died in Her Sleep (1996).

In an elegant essay review of Gregerson’s fifth book, The Selvage (2012) (“‘A Ravishing Mind’: On the Pleasures of Linda Gregerson’s Poems,” published in this Review), Jonathan Farmer writes of the dramatic leap Gregerson made from her first book, Fire in the Conservatory (1982), to The Woman Who Died in Her Sleep, published 14 years later. Though animated by the questions that remain central to Gregerson’s work, Fire in the Conservatory was slightly enervated by left-justified blocks of lines, fairly traditional strophes, and stichic shapes that belie the poems’ mental, imaginative, vocative, and theatrical impulses. By contrast, the second collection, as Farmer puts it, “introduces the form that still, even in its absence, defines her poetry, a jagged tercet with an extremely short second line.” Gregerson herself has said that the tercets she began to use in her second book:

were the first formal vehicle I found that seemed to me to be properly flexible, and true. Especially important was that second, deeply indented line, the “pivot line” as I conceived it, often only a single metrical foot long. It gave me a kind of skeletal resistance, something that syntax could work against, and thus it became a true generative proposition, not just a kind of packaging. The lineation produced the poem.

I agree with Farmer that Gregerson made a crucial advance in the second book by “figuring out how to write according to her own temperament, rather than the temperament of the time” — which is, of course, the challenge for all poets, in all times. Discovering the forms to embody one’s thinking (and vice versa) is not something one does just once, either; it is an ongoing dance, and Gregerson has continued to experiment formally throughout her writing life. In a 2009 Memorious interview with Adam Day, Gregerson says,

After Waterborne [2002], I knew I had to make a formal break. I’d based that book, and the one before, almost exclusively on a tercet I had developed in the ’90s. It saved my life, that tercet, but I was beginning to know it too well. I was frightened to death, frankly, about making the change; it was like learning to walk again.

And learn she did, adopting terraced, drop-line quatrains and alternating left-justified and indented couplets that reinforce, often in a choral call-and-response manner, persona poems from the perspectives of, among other figures, characters from Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Yet revisiting The Woman Who Died in Her Sleep in its entirety has convinced me that Gregerson’s intrepid, life-saving tercets are far more than a generative vehicle for Gregerson’s fluid, prodigious thought process. The tercets as she deploys them — the deft enjambments, the splitting of words into their revelatory parts, the acoustical italicization, the asides, the “beats,” the spiraling helical DNA of the three-line units in sequence — show us how to “read” Gregerson in all of her modes. Consider these lines from “Bleedthrough,” a poem dedicated to the painter Helen Frankenthaler that, among other things, concerns the way women artists see and create through the body:

As when, in bright daylight, she closes

her eyes

but doesn’t turn her face away,

or — this is more like it — closes her eyes

in order

to take the brightness in,

and the sun-struck coursing of blood through the

lids

becomes an exorbitant field to which

there is

no outside,

this first plague of being-in-place, this stain

of chemical proneness, leaves so little

room

for argument. You’d think

the natural ground of seeing when we see

no object

but the self were rage.

The effect of these tercets, with their spaces for pausing, their syntactic swerve, their switchbacking tangents, their punctum push-off nodes, is something akin to what happens when an actor goes off book; the lines live in the mouth and body, no longer confined to the page.

Gregerson often brings at least two stories into counterpoint. In this collection’s title poem, for instance, she interweaves a meditation on a Jeffrey Silverthorne photograph of an autopsied woman with a narrative of her trip to an art museum with her five-year-old daughter. Yet she is savvy enough never to traffic in clean binaries — or in extremes of any kind. As attracted as she is to what she calls, in “Mother Ruin,” the simplifying mind of snow, she is aware of how “always the rain // insinuates, which is death to abide by, / and always the honey-mouthed wind, / till the fastness that made things all of a piece / dissolves.” Whether a Gregerson poem is actually written in her signature tercets or not, she always implicates an unsettling third element. This element may be the reader, whom she queries in the title poem:

[…] Have I

told you — do you know for yourself — how the

sweetness

of creation may be summed up in the lightfall

on a young girl’s cheek? The wound

she hadn’t yet

learned to ignore, the mortal one, was where

the child had once been joined

to something else.

And later, when the juxtaposition of the photograph and the young daughter brings to mind her mother’s death:

[…] They took

my mother’s teeth away — they had

to, I can

understand — the morphine I’d bullied them

into providing was meager

and frequently

late. And so my mother’s face was not

the face I knew. But, reader,

her

fine forehead was a blessing on the place.

The Gregersonian tercet form allows the speaker to have things “and/or” and “none/all.” The shape, the fabric, the woven whole, is there, but so is, always, the insinuating hole.

Perhaps the best indication of Gregerson’s aesthetic can be gleaned from her comments on contemporary theater. Discussing Robert Wilson’s the CIVIL warS in her interview with Adam Day, Gregerson says:

Wilson saturates the stage with so much magic — aural, visual, narrative, non-narrative, mimetic, non-mimetic, textual, musical — that each member of the audience is transformed into an active collaborator. One must choose which paths to follow, one cannot possibly follow them all. Nor is it a cluttered field, never: it is exquisitely choreographed, performed with impeccable discipline, so one encounters, as is almost never the case in life, a field of superabundance with no dilution, no scrambling, no muddiness. Just this fabulous accession of plenitude: one follows first this thread, then another, keeping one or two or, fleetingly, three others in mind; then one lets it go to pick up another. And none of the paths is wrong; everywhere one turns is right. Right, then right again. And of course, each performance, for each audience member as also for the aggregate, is different. It’s like discovering one can fly.

The Woman Who Died in Her Sleep is an important and beautiful book, which bears reading and rereading in its entirety. It represents what one hopes for in a second collection — a deepened assurance, a farther reach, and a grappling with eternal truths, particularly about the vulnerability of children and nature’s imperviousness to the human will. In “With Emma at the Ladies-Only Swimming Pond on Hampstead Heath,” the speaker acknowledges that her growing daughter, who has been subjected for years not only to bed and bath-time rules but also to a more recent spell of maternal “applied / French Braids,” is beginning to push for independence. As the two swim together in makeshift bathing suits, the speaker says:

She’s eight now. She will rather

die than do this in a year or two

and lobbies,

even as we swim, to be allowed to cut

her hair. I do, dear girl, I will

give up

this honey-colored metric of augmented

thirds, but not (shall we climb

on the raft

for a while?) not yet.

I am abidingly grateful for the chance to explore the imaginative realms of Linda Gregerson’s braided, “augmented thirds” in her early, current, and future poems.

¤

I had in mind to pair Rachel Richardson’s recently released second collection Hundred-Year Wave with Gregerson’s The Woman Who Died in Her Sleep long before I realized that Richardson holds an MFA from the University of Michigan, where she was taught by Gregerson herself.

An endorsement by Gregerson graces the back cover of Richardson’s first book, Copperhead, which appeared in 2011 and was a finalist for the Eric Hoffer Award and the Paterson Poetry Prize. In Copperhead, Richardson concerned herself primarily with the American South — that is, with the South’s vexed legacy of racism, defeat, pride, culpability, familial hierarchy, and tradition, and with its swamps, plantations, fields, and blues. The poems in Hundred-Year Wave, on the other hand, take us largely north of the Mason-Dixon line. The poet casts what Emily Dickinson would call a “New Englandly” filter over her lens and focuses our attention on shorelines, whaling, sailing, and other nautical and navigational motions.

Seamus Heaney has written that a chief function of poetry is to “write place into imaginative reality.” The place at this book’s heart is the sea — a frontier transcending geography that tropes the natal inner sea in which we live before we are born. The speaker in Hundred-Year Wave faces the kind of life changes — the premature deaths of ancestors, the very present death of elderly loved ones, the birth of one’s own children — that can turn familiar terra firma into unstable ocean swell. As explorer Ernest Shackleton puts it in the book’s epigraph, “I called to the other men that the sky was clearing, and then, a moment later, realized that what I had seen was not a rift in the clouds but the white crest of an enormous wave.”

Richardson’s personal poems are interwoven with famous shipwrecks, drownings, cetacean mysteries. Here, for example, is the poem “Erosion [Eros]”:

Ocean baits the rock —

calls the layers of schist [what fated her]

to reveal themselves, [what she meets]

split wide.

Like that girl [downward years]

you were, waiting

at the foreign station [foamless weirs]

for a train that wouldn’t come

for hours.

Silence

in the blown-out air [and fades]

and even the shuffle of birds [pounding wave]

flapping into the shelter a kind

of silence, impacted.

Ocean baits the rock — [as it should be]

whispers come, then licks

straight up the flank. [ever could be]

And you, still a girl

somewhere

in your mind,

still have not boarded, [have striven]

now stand at the cliff edge,

extend your arm [changed familiar tree]

and reach — [stairway to the sea]

[are driven]

At the left-justified margin we have a narration that compares the erosion of a rocky shoreline by oceanic forces with the personal predicament of a woman caught in what Anne Carson calls the bittersweet “reach” of Eros. Bracketed to the right are shards of language, disrupted couplets that seem distilled from the “poem proper”; these phrases excavate the “eros” contained in “erosion,” orthographically and experientially.

If Copperhead was driven by a need to acknowledge and perhaps forgive the inheritances of a regional past, the engine of Hundred-Year Wave is desire — the immense force, as Richardson writes in “Canticle in the Fish’s Belly,” that “outlasts all our vows.” Richardson’s first two books can be said to trace the natural trajectory many poets take, albeit with a rare linguistic and imaginative assurance: the first volume digs into the past, childhood, family; the second broadens its scope, situating family in contexts that shape and also transcend history, at times offering guarded hope.

Hundred-Year Wave’s last poem is titled, fittingly, “Shearwater,” a term for birds accustomed to moving between air, water, and land. It is difficult not to compare this species to the first book’s “copperhead” — a dangerous Southern snake, but also a Southerner with Northern allegiances. Rather than belonging to one world or another, shearwaters thread their way through elemental boundaries. In the poem, Richardson’s speaker recounts the gestation and birth of a child: “You were given feet but had never touched / them to earth. You were given the sea / and you fed upon it for months.” After the baby is born — “and you were silent, and the tide in me / receded” — she recalls the shearwaters that followed ships, the “slow sweep / of them riding the wind’s current. / The stretch of them, hovering, / cruciform […]” She remembers following their progress for hours:

[…] their trailing:

as if stillness itself drifted toward me.

I thought it was my life.

Then someone lifted you up,

and there was a sound,

and they laid you on me, breathing.

Worlds invading words, words creating worlds — these are the great gifts of Linda Gregerson’s and Rachel Richardson’s second books.

¤

LARB Contributor

Lisa Russ Spaar is a contemporary American poet, professor, and essayist. She is currently a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Virginia and the director of the Area Program in Poetry Writing. She is the author of numerous books of poetry, including Vanitas, Rough: Poems, and Satin Cash: Poems. Her most recent book is Madrigalia: New & Selected Poems (Persea, 2021), and her debut novel, Paradise Close, was published by Persea in May 2022. Her poem “Temple Gaudete,” published in IMAGE Journal, won a 2016 Pushcart Prize.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Second Acts: A Second Look at Second Books of Poetry by James Tate and Sam Taylor

Lisa Russ Spaar looks to poets Sam Taylor and James Tate to explay why the two fundamental modes of lyric poetry are crying and laughing.

Second Acts: A Second Look at Second Books of Poetry by Carl Phillips

How Carl Phillips became one of America's most eminent writers.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!