Scarcely Schwarzeneggarian: Alex Segura’s South Florida Crime Fiction

Alex Segura's "Down the Dark Street" offers a new high point for south Florida crime fiction.

By Les StandifordAugust 1, 2016

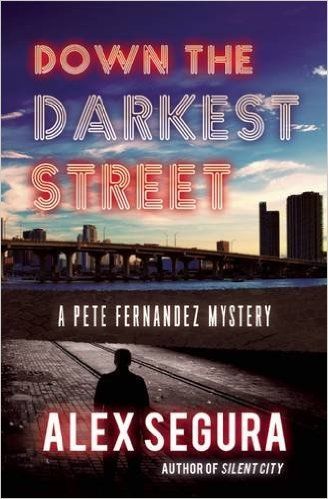

Down the Darkest Street by Alex Segura. Polis Books. 304 pages.

THE CRIME THRILLER is as hoary a form to South Florida as the hipster poem is to San Francisco as the Woody Allen film is to Gotham. And while the beat ode may have faded into history and Allen has rambled away from New York, the paeans penned to murder and mayhem in Miami show no sign of abating. Douglas Fairbairn (Street 8) and Charles Willeford (Kiss Your Ass Good-Bye) pioneered South Florida noir in the ’70s and ’80s, and there has been a steady stream of acolytes following ever since, from the loopy criminalities of Carl Hiaasen to the mean-streets intrigues of Barbara Parker, James W. Hall, James Grippando, and so many more. Someday, Miami may be known for its restrained novels of quiet domesticity (check out Susanna Daniel’s lovely Stiltsville), but for now, the form that seems to body forth the energy and ruggedness and core identity of what is for all intents a frontier city is the novel of crime and — sometimes — punishment.

Add to the list of those plumbing the darker depths of the so-called city of dreams the name of Alex Segura, whose Down the Darkest Street is a follow-up effort to his debut thriller Silent City (2013) which also featured the exploits of down on his luck reporter and erstwhile investigator Pete Fernandez. Segura is a Miami native now living in New York City whose résumé includes comic book and graphic novel writing (Archie Meets KISS) and membership in the indie rock band Faulkner Detectives. Clearly, however, the grip of grim Miami has not lost its hold on Segura despite his decampment to bright and cheery New York.

In this new installment, ex-reporter Fernandez struggles to emerge from a morass of depression and alcoholism brought on by the many losses and traumas visited upon him in Silent City. He’s lost his job at the Miami Times, his wife has remarried a glib entrepreneur, and he is reduced to a part-time gig at an out-of-the-way bookstore where the only customers seem to be those summoned there to assault or harass our hero. So far as any gumshoe work goes, he hasn’t had much luck there either, but when a series of young women are abducted and gruesomely murdered in Miami, Pete finds himself drawn to investigate, even though his ex-wife Emily pleads with him not to get involved. She has split with her second husband as the novel opens and has prevailed upon Pete to let her move back in while she gets her head straight about things. She suspects, rightly as it turns out, that his sleuthing will prove a major distraction to any possibilities of their reconciliation.

What compels Pete to pull himself out of his malaise and join forces with his former Times colleague Kathy Bently in pursuit of a serial killer is not entirely clear or completely plausible, but the mixed inheritance of satisfaction and recrimination that he carries from his experiences in Silent City seems to have a lot to do with it. Before long, he and Bently are doggedly pursuing leads that a corrupt Miami PD seems disinterested in, and soon after, Pete is confronted by a pair of FBI agents warning him to stay off the case. Pete, however, has become convinced that the perpetrator is a copycat killer inexplicably drawn to recreate a series of Ted Bundy–style killings of 30 years previous, and scarcely has he formulated these suspicions to those close to him than he is beaten into a stupor (this happens quite a few times in the book) in a dark parking lot by the killer himself. If he knows what is good for him, the masked man says, Pete will recuse himself from poking around into things that don’t concern him. Pete, however, is not one to give up on a bad idea, and scant days later, he and Bently are nearly killed when his house is firebombed and his cat immolated.

All this negative energy has sent his ex packing, and her departure, along with the various dead ends and disappointments tied to his fruitless digging send Pete back to the solace of the bottle. Only when it becomes apparent that his ex is in the killer’s crosshairs does Pete rally for one last opportunity to redeem a miserable existence.

One of the more intriguing aspects of Segura’s book is his refusal to equip his hero for anything that remotely resembles swashbuckling derring-do or swordsmanship of a more personal nature. Pete is about as incompetent a fighter and a lover as all the rest of us, facts which Segura reminds us of on several occasions. The opening chapter of the book, in fact, is devoted to his absorption of a brutal beating that turns out to have virtually nothing to do with the plot: “Pete Fernandez didn’t see the kick coming,” goes the first sentence. “The boot crashed into his jaw, sending him farther into the dank alley. The two men paused to see if Pete had any plans to fight back. He didn’t. He felt blood trickle down his face.” Scarcely Schwarzeneggarian.

But if Pete is not a stereotypical PI, the plot itself moves forward far more conventionally, with corrupt cops and FBI agents stonewalling the agency of justice because that is their nature and perpetrators apparently fueled by the vapors of random lunacy. Furthermore, there is very little about the machinations that suggest the story is in any way born of the place where it occurs. Segura is dutiful in making reference to various Miami locations, including the Versailles Restaurant, the now-demolished Miami Herald building, and the beat-down landscape of rural Homestead and the seedier sections of swanky Coral Gables. There is even one brief reference to the fact that most of the killer’s victims are poor and Latina and of little concern, relatively speaking, to certain power structures in the community. But that angle goes nowhere, and there are also a few lapses in local knowledge: anyone driving from the Kendall area to distant Homestead and in a hurry about it would use the Florida turnpike, not the surface streets, for instance, and the Don Shula Expressway goes nowhere near the infamous “spaghetti bowl” intersection of I-95, the Florida Turnpike, and the Palmetto Expressway. Still, there is something engaging about Pete’s Labrador-like steadfastness and his everyman-styled ineptitude, and if Segura has brought along something from his experiences as a comic book writer, it is a knowledge of how to keep a story moving, even if logic is not always the fuel of the plot’s engine.

Various supporting characters such as Bently, ex-wife Emily, and bookstore owner-cum-gangsta Dave are colorful and engagingly drawn, their generally demeaning-toward-Pete repartee spot-on and enjoyable. One witness mentions to reporter Bently that a victim’s married boyfriend broke off an affair with her missing roommate after promising they’d work something out once he’d left his wife. “They always say that,” no-nonsense Bently remarks, “but they never do.”

One might read Down the Darkest Street as if it were something of a fever dream or a graphic novel sans illustrations, and come away pleased with the effect. If you or I were asked to stand in for Bogart or Mitchum, we’d probably perform about as well as Pete Fernandez and there is no small amount of pleasure in watching that.

¤

LARB Contributor

Les Standiford directs the Creative Writing Program at Florida International University in Miami and is the author of two dozen books and novels, including the John Deal series of crime thrillers and, most recently, Water to the Angels: William Mulholland, His Monumental Aqueduct and the Rise of Los Angeles.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Grave Disruptions

"I’m not for the status quo, so I don't know how to write anything but untidy, slightly melancholy endings."

The Dark Triangle: An Interview with Scott Adlerberg

Alex Segura interviews Scott Adlerberg.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!