EVERY YEAR gets harder for us workers. The employer takes more and gives less. The individual shoulders the risks, with all benefits credited to the corporation. This isn’t how it used to be. The first thing I was taught as a young (paid) intern in the late 1970s was how to pad my expense account. My first day as a news cameraman, the reporter asked me to drive, so she could roll us a joint.

I’m not a big fan of Charles Bukowski, but what strikes me when I read his early stories is how easily he was able to find work. Generally drunk, utterly unreliable, he gets a job, doesn’t show up, it takes a few weeks until he gets fired, and then, no problem, he finds another gig. Unemployment is never a worry. Incompetence never precludes employment. Today, a man with his penchant for drink and his lack of work ethic would be dumpster diving for food rather than easily finding gainful employment.

Think of the guy who had your job 20 or 30 years ago. Most likely, unless you are a professional athlete or a CEO, he made more money, had more fun, and worked shorter hours than you do. Back in the early 1980s, right before I became a union cameraman, a friend of mine, already in the union, stole the news director’s car, drove a gaggle of co-workers from bar to bar, got utterly shitfaced drunk, and, as one might expect, totaled the vehicle. He did not get fired. He did receive a stern talking-to, but he was never in any danger of losing his job. Imagine that today.

Case in point — P is a journalist in his late 30s. A few years ago he got a promotion: Kabul Bureau Chief for a leading international news agency. Exciting, if a tad dangerous, even though his employer didn’t give him a raise. Right after he arrived in Afghanistan, he received a disturbing email. No, not from the Taliban, but rather from the head office. The boys in accounting informed him that, according to their calculations, establishing residence in Central Asia would lower his tax bill dramatically. So, instead of letting him keep the windfall, the firm decided to cut his pay, by precisely that amount. He was agog. Per diems and tax breaks are traditional perquisites for working in war zones, and now the company was telling him that it considered any benefit accruing to him due to his hazardous assignment as corporate property. Other than quitting his job, P had little recourse, so the news agency, not the journalist, got the tax break.

I’m lucky. I’m just old enough that I managed a glimpse of the golden days of labor. In 1987, when I joined the union, the older guys were already grumbling that the tide was turning, but we still had it good. Over 8 hours we got paid time and a half, missing a meal got us another $15 an hour, we tagged on an hour after our shift to “clean up” and put away our gear. One day, because of various penalties and overtime, I made close to $1,500 just sitting in a chair running a sound mixer. I felt I was getting one over on “the man.” I felt I was making more money than I deserved. Nobody feels that way any more.

The obstreperousness of labor unions in the 1970s was probably a prerequisite for their destruction in the 1980s. Without the miners bleeding Britain during the 1979 “Winter of Discontent,” Thatcher’s policies would have been unthinkable. The high-inflation 1970s is a byword for economic havoc, but for most workers they were pretty good. Even adjusted for inflation, wages grew faster in the 1970s than they have ever since. Workers did well. It was capital that got hammered. Corporate profitability declined and stocks and bonds lost three-quarters of their value between 1966 and 1982. In response, Reagan and Thatcher raised interest rates, engineered a recession, drove up unemployment, smashed inflation, and changed the course of history. Reagan and Thatcher embodied the counterattack of capital, and labor never recovered. Even today, with the economy stagnant, corporate profits still keep going up. Median male real wages are lower than they were in 1973.

On the micro level, screwing the worker is a brilliant policy for corporations. The less they pay staff, the more shareholders and CEOs get to keep. The problem is on the macro level. Workers are also consumers, and if they are paid less, they will also spend less. Every year, because of productivity increases, we are able to produce more output with fewer inputs of labor and capital. Supply rises, and for the economy to grow, demand must go up too.

Before the Reagan/Thatcher revolution of the 1980s, demand grew because wages grew. During the postwar golden age, from 1950 to 1973, productivity increases almost immediately translated into wage hikes. No more. The corporation keeps productivity gains for itself. Since Reagan/Thatcher, demand could only grow if we were all willing to go ever deeper into debt. And now those days are over too. The debt-fueled consumption paradigm ended with the financial crisis.

In Part One of this article, A Brief Glossary of Financial Cataclysm, I explained that had banks gambled with their own money, there would have been no crisis. But since banks make 97 percent of their trades and loans with depositors’ money, it only took a three percent decline in the value of their assets to make them insolvent. That is to say, in the fall of 2008, even if the banks had sold everything they owned, from stocks, bonds, credit derivative swaps, mortgage-backed securities, private jets, to the art on the wall, most of them would have been unable to come up with enough money to pay off their depositors.

When the big wholesale lenders realized the banks were bankrupt, they pulled their cash. Bank runs easily become self-fulfilling prophecies. No one wants to be the last in line, holding a worthless IOU. The government then stepped in and saved the day. In the fall of 2008, had central banks not guaranteed loans to the banks to replace the private money being frantically yanked out, you and I could easily have found ourselves standing at the ATM, card in the machine, being told the money we thought was safe in our account was gone forever.

In Part One, I analyzed how we got into this mess. Now I’ll describe how we should get out.

¤

The nine most terrifying words in the English language are, “I’m from the government and I’m here to help.”

— Ronald Reagan

Possibly the most destructive legacy of smiling Ronald Reagan is the easy and thoughtless way he taught us to scorn our government. The Federal government put a man on the moon, built the interstate highway system, defeated the Nazis, and created the internet, but most of us treat it with less regard than we do some second-rate actor or fashion designer. The irritation we feel standing in line at the Department of Motor Vehicles may partly explain this attitude, but the financial crisis should have put it to rest. In 2008, the only thing that saved the world from utter financial collapse, that saved the money in your and my bank accounts from disappearing into the ether, was prompt and efficient action by the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, and the European Central Bank. Had they not provided billions of dollars to shore up the financial system, millions of us would have lost all the money we blithely assumed was sitting safely in our bank accounts. Without government intervention, the financial crisis could have been much worse.

It could have been much worse, but it also could have been better. Government had the tools to stop the recession, create jobs, and generally make the life of the average American safer, richer, and more prosperous, but it didn’t use them. In part, this was because conventional wisdom proclaimed government policy ineffective, but mostly because elites decided that the fate of the average American didn’t really matter. The government reaction to the financial crisis mainly helped those who created the problem in the first place. Stock prices have recovered since 2008, but wages have not.

The financial crisis and subsequent recession will mark the end of the Reagan/Thatcher era, just as Reagan/Thatcher marked the end of the postwar golden age. Before 1980, swiftly rising wages were the engine of economic growth. After 1980, it was exploding debt. Real median wages doubled between 1950 and 1970. Today, most of us are poorer than our parents were at our age. Since 1982, only a massive increase in debt allowed the world economy to expand. Once the level of debt stopped growing, so did the economy. The stagnation of the last seven years is purely due to the fact that we are paying down loans rather than borrowing more.

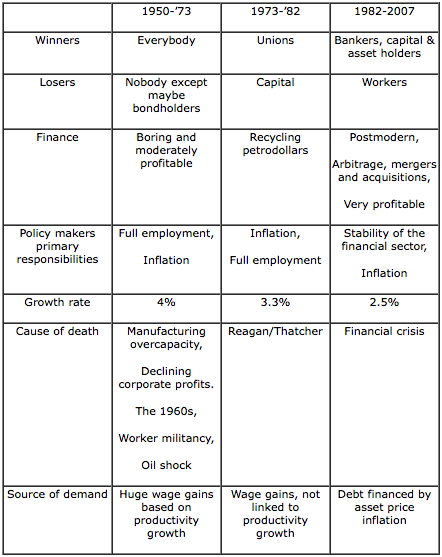

Three Eras

The financial crisis obliterated the debt-fueled consumption paradigm. Not only did fear of going bust make banks much more careful about spreading their largesse, but also households, watching their wealth disappear while their debts remained constant, prudently decided to borrow less and save more. On an individual basis, this is a sensible policy. When your debts exceed your assets, spending more than you earn is self-destructive.

But what is true for an individual is not true for society as a whole. When all of us are saving rather than spending, the economy inevitably contracts. Any dollar I sock away, I am not spending in your store. And if your sales are decreasing, you won’t be investing in new machinery, and you will be firing workers instead. Fired workers (or workers who fear losing their jobs) won’t be splashing out on consumer durables. The financial crisis, by reducing banks’ willingness to lend and the private sector’s to borrow, has trapped us in pernicious feedback loop:

Less spending → Higher unemployment → Less spending

The free market, all by itself, cannot break this loop. Government can. So far, it hasn’t tried.

The government has two tools to influence the economy: monetary policy and fiscal policy. Monetary policy is the control of interest rates, and the first thing governments around the world did after the financial crisis was to cut rates. Easy money had saved financial markets from their self-inflicted wounds several times before — in 1982, in 1987, in 1998, in 2000 — and policy makers expected it would again. Monetary policy is generally a shockingly effective weapon. Next to lust and gravity, interest rates may be the most powerful force in the universe. Everything from the Reagan/Thatcher revolution to the long boom in stock and bond prices is in large measure due to changes in interest rates.

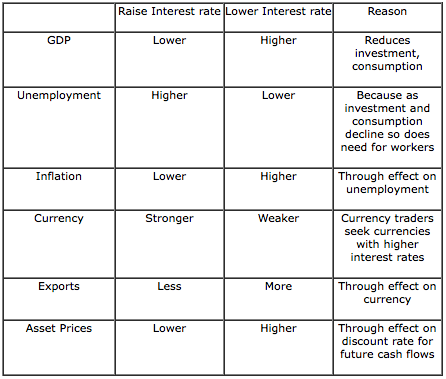

By making money cheaper, interest rate cuts increase the desire to borrow and decrease the desire to save. Cheap money stimulates investment and consumption, and so GDP goes up. Stock, bond, and house prices also rise. As economic activity increases, unemployment naturally falls. Cut rates and you stimulate the economy. Raise them and inflation, investment, employment, GDP, house prices, bond prices, stock prices all decline. For most of us, these effects are not intuitive, but finance boffins know them in their sleep. Below, a handy table for you to cut out, laminate, and keep in your wallet.

Effects of Interest Rate Changes

Unfortunately, these days, monetary policy does not look as all-powerful as it did just a few years ago. Since 2008, we have had the lowest interest rates in recorded history, and still the economy is in the toilet. (By no means am I advocating a rate hike. Were interest rates higher, things would be much worse.)

The recovery, technically almost five years old, remains pathetically anemic. That is because interest rates cannot go below zero. The interest rate at equilibrium is supposed to balance our collective desire to save and our desire to invest. But today, because of a global savings glut and limited need for capital goods, even microscopic interest rates are not low enough to balance the two. Right now for savings to match investment, interest rates would actually have to be negative, and that can be tricky, if not impossible, to engineer.

In the jargon, monetary policy is stuck at the “zero lower bound.” You can’t cut rates below zero, so you cannot inspire enough investment to soak up spare savings. If savings exceed desired investment, the economy remains slack and supply outstrips demand. Quantitative Easing 1, 2, and 3 were attempts at “unconventional” monetary policy, using the ability of central banks to make money out of thin air and pump it into the financial system in the hopes this would encourage banks to start lending. So far, seven years into the game, the results are disappointing. Quantitative easing has made more than a few bankers rich, but it hasn’t done all that much for anybody else.

Fortunately government has another tool. Unfortunately, it hasn’t much wanted to use it.

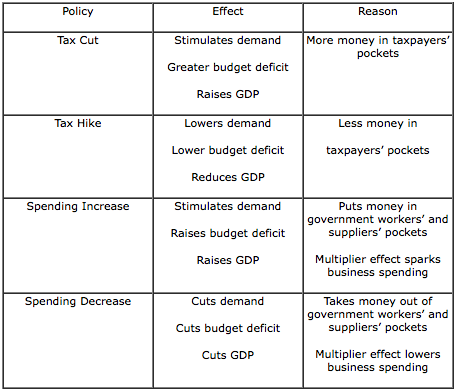

Fiscal policy is only 80 years old, invented in the wake of the Great Depression. It is the use of government taxation and spending to affect the larger economy. If the government taxes more than it spends, it pulls money out of the economy and so shrinks it. If it spends more than it takes in, its excess spending puts money into people’s wallets, and so the economy grows.

Effects of Fiscal Policy

Perhaps the main prejudice against fiscal policy is that government spending helps poor people. Republicans favor fiscal policy when it involves tax cuts for the rich, not so much when it means spending on the rest of us. Whenever Republicans want a tax cut, they get the Keynesian religion. They tell us, quite correctly, that tax cuts, if not matched by spending cuts, are stimulative because they put money in taxpayers’ pockets. Unfortunately, tax cuts generally favor the rich, and rich people can save rather than spend their windfall, which means tax cuts are an incredibly inefficient way to stimulate demand and so the broader economy.

On the other hand, increased government spending is remarkably powerful in battling economic stagnation. In 1938, US unemployment was almost 20 percent. By 1944, it was barely one percent. Everybody knows WWII ended the Great Depression, but it is vital to remember that it wasn’t the slaughter of soldiers or the destruction of cities that boosted employment. It was government deficit spending. Had the government spent the same amount of money on ukulele lessons for every American as it did on defeating the Nazis, the economic effect would have been identical.

The Great Depression ended because the government created money and put it in the pockets of the previously unemployed. Those workers spent that money, thus giving the private sector reason to hire and invest, and that is what finally created jobs and engendered the longest boom in human history. Today, instead, the government is creating money and putting it into the reserve accounts of banks. There it sits, its trickle-down effect so far negligible.

Government deficit spending can end the Great Recession. Proponents of austerity and their fellow travelers in the media argue persuasively that when families are cutting spending, government ought to cut back as well. While this seems intuitively obvious, it is actually sheer economic illiteracy.

The most basic macroeconomic equation tells us Y = C+ I + G. GDP equals consumption plus investment plus government spending. If households are consuming less and firms are investing less (as they are today), then government spending must grow for the economy not to contract. Cutting government spending during a slump only makes the slump last longer.

Our problem today, indeed capitalism’s only Achilles’ heel, is lack of demand. Every year we can produce more and more stuff with fewer workers and less capital. Productivity rises inexorably, raising supply. Demand must grow alongside it. Since the Great Depression we have solved the problem of demand three ways: war (from 1939 to 1945), rising wages (from 1945 to 1980), and debt (from 1982 to 2007). The collapse of the debt-fueled consumption paradigm tells us we need to find a new way.

¤

I see an America in which we have abolished hunger, provided the means for every family in the Nation to obtain a minimum income, made enormous progress in providing better housing, faster transportation, improved health, and superior education.

— Richard Nixon

It is a sign of how far political discourse has moved to the right that in many ways Richard Nixon was a more liberal president than Barack Obama. In 1969, Nixon proposed a Basic Income Guarantee, which would give every American enough money to survive. In the optimistic 1960s, it seemed obvious that a rich country like America could afford to eliminate poverty. Today, of course, we are even richer, but much less generous. Conservatives like Nixon supported the Basic Income Guarantee because it gave money directly to every citizen, thus eliminating poverty without creating a federal bureaucracy. Nixon’s “negative income tax,” as it was also called, passed the House of Representatives and came very close to passing the Senate. Had it, the world would be different today.

The Basic Income Guarantee has a number of virtues. The first, and most obvious, is that it provides a safety net for all citizens. By giving money to everyone, it is fair. Since it is not means tested, it does not penalize work. Since it provides everyone enough money to survive, it lessens the need for the private sector to pay workers a living wage. And it does its bit to foster equality in a society that keeps becoming ever more stratified. But its cardinal virtue, and the reason I am convinced it will eventually come to pass, is that it takes on our economy’s most central problem — lack of demand.

For those of us well over the poverty line, the Basic Income Guarantee will function just like a tax cut. But unlike most tax cuts, which favor the rich, the great majority of recipients will spend their newfound cash right away, just as the economy requires. That spending, on goods and services provided by the private sector, will ripple through the economy, giving entrepreneurs reason to hire new workers or invest in productive capacity. Bang, our never-ending recession is over, and we don’t even need to bomb Dresden!

Perhaps you ask, can we afford it? First, if you have a basic income guarantee, all other income programs can begin to be phased out. If every citizen receives a subsistence-level income, Social Security for retired Americans can certainly be trimmed. But on a deeper level, of course we can afford it. Even though most Americans are working harder for less money and with less job security than their parents did, technology has made us so much more productive than we were in their day. We should live like kings, not serfs. The notion that labor-saving productivity gains will make the next generation poorer than the previous is deeply disturbing. A basic income is redistributive, shifting purchasing power down the economic scale, but considering how much richer our society as a whole is than it was a generation ago, and considering how little of that wealth has trickled down to the average American, that isn’t a bad thing.

Maybe the biggest plus of a Basic Income Guarantee, other than solving capitalism’s demand dilemma now that debt-fueled consumption is past its sell-by date, is that it will restore workers’ bargaining power. I recently read a brilliant essay by Connor Kilpatrick on libertarianism. He closed his article explaining why libertarians have such antipathy to the welfare state:

First, they’ll talk about the deficit and say we just can’t afford entitlement programs. Well, that’s obviously a joke, so move on. Then they’ll say that it gives the government tyrannical power. Okay. Let me know when the Danes open a Guantánamo Bay in Greenland.

Here’s the real reason libertarians hate the idea. The welfare state is a check against servility towards the rich. A strong welfare state would give us the power to say Fuck You to our bosses — this is the power to say “I’m gonna work odd jobs for twenty hours a week while I work on my driftwood sculptures and play keyboards in my chillwave band. And I’ll still be able to go to the doctor and make rent.”

Sounds like freedom to me.

¤

Supply shocks are intractable. Just wanting to feed the hungry does not create more grain during a famine. Demand problems, thankfully, can be solved with mere political will. We are a rich society, richer than our grandparents ever dreamed possible. Let’s live like it. We should be more prosperous than our parents were. Let’s make it so. The only reason standards of living are not improving is that productivity gains go almost exclusively to the top one percent. The only reason the economy is stagnant is because the average American doesn’t have enough money in his or her pocket. A Basic Income Guarantee solves both problems.

We can restore our middle class.

Call your Congressman.

Demand a Basic Income Guarantee for every American.

¤

LARB Contributor

Tom Streithorst has been a union member, an entrepreneur, a war cameraman, a commercials director, a journalist. These days, he mostly does voiceovers and thinks about economic history. An American in London, he’s been writing for magazines on both sides of the pond since 2008. He is currently working on a book on how the incredible productive power of capitalism and technology have the potential to bring us all prosperity and happiness but so far, we keep screwing it up. He also writes a regular column about economics at pieria.co.uk.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Why the World Needs a Pay Raise

Stewart Lansley on why low wages create an unsustainable economy, and why people around the globe need a raise.

A Brief Glossary of Financial Cataclysm

The Big Crash 101: how to understand the evaporation of trillions of dollars.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!