Revising the History of DDT’s Long-Tailed Legacy

Rebecca Altman appreciates Elena Conis’s new book, “How to Sell a Poison: The Rise, Fall, and Toxic Return of DDT.”

By Rebecca AltmanJune 17, 2022

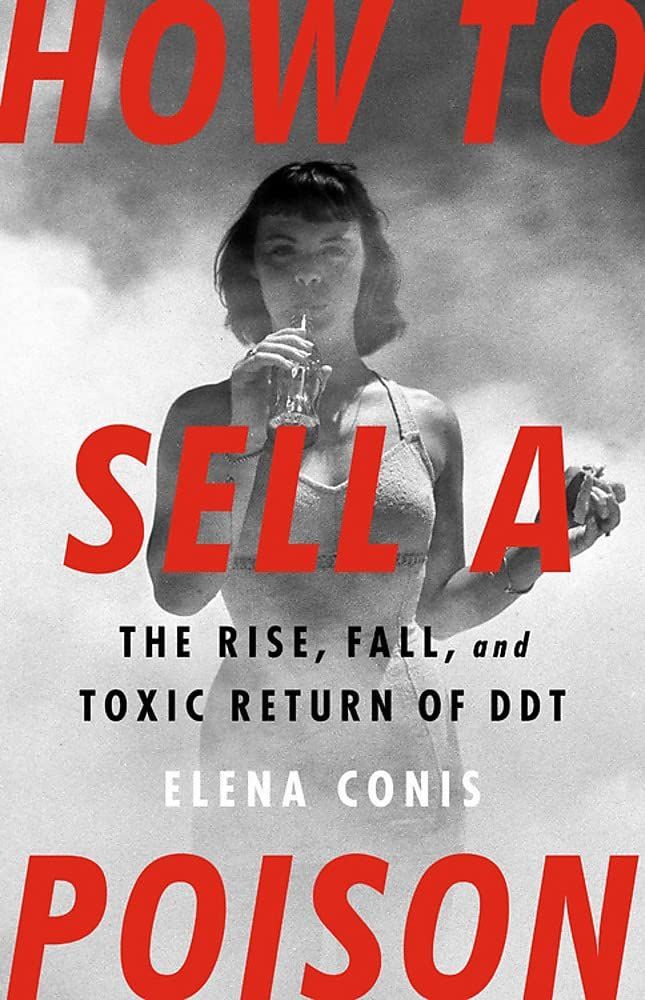

How to Sell a Poison: The Rise, Fall, and Toxic Return of DDT by Elena Conis. Bold Type Books. 400 pages.

BY THE FALL of 1945, the writer Primo Levi had survived Auschwitz, scarlet fever, and pleurisy, as well as nearly 10 disorienting months of displacement. Though the Red Army had liberated Auschwitz in January, Levi had yet to make it home to Italy. The rail network was in disarray, and a series of dilapidated trains had diverted him across Eastern Europe, through Belarus, Ukraine, Moldavia, Romania, Slovakia, before he entered Austria and finally fell into the hands of the Americans.

What loomed now was the specter of lice-spread typhus. And so, upon disembarking in Austria, Levi was met by US soldiers in “science-fiction” garb, coveralls, and gas masks, who distributed a powdered pesticide around his collar, into his pockets, up his cuffs, and down into the pulled loose waistband of his ragged trousers. The dust, he wrote 15 years later in The Truce, was the now storied insecticide dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, known as DDT — and as American, he wrote, as penicillin or Jeeps, those “squat, graceless military vehicles” he’d seen rumbling triumphantly around St. Valentin.

Levi was a doctor of chemistry. At the time, he may not have known what the white powder was called, but if someone had told him its formula — C

14

H

9

Cl

5

— he would have known of its kind. Just a few years earlier, while a student at the University of Turin, he had worked with similar compounds of carbon and chlorine as part of his doctoral research.

More than a half-century earlier, DDT had been described in the chemical literature following its synthesis by Othmar Zeidler at the University of Strasbourg. Nothing practical became of the compound until 1939, when the future Nobel Prize–winning chemist Paul Hermann Müller, searching for new pesticides for the Swiss company J. R. Geigy, determined Zeidler’s DDT could indeed kill a fly.

Geigy spread news of DDT’s insecticidal potential, alerting Germany, Britain, and the United States, who contracted several chemical manufacturers to begin production. More than a dozen firms made DDT for the Allied effort, including major chemical manufacturers, like DuPont, Monsanto, and Sherwin-Williams, and lesser-known firms like Michigan Chemical, based in St. Louis, Michigan, and now one of many places living out the long legacy of World War II technologies like DDT.

¤

“I heard you liked history,” Lynn Roslund said upon picking me up at the Detroit airport, a couple hours’ drive from St. Louis. I met him outside the baggage claim where he handed me — if you can believe it — a can of World War II–era DDT. Levi’s Italian compatriots might have recognized it.

St. Louis is situated in the middle of Michigan on an ancient deposit of petroleum and salt-rich brine. Before the chemical industry tapped these resources, St. Louis had been a place to “take waters,” Roslund told me — to bathe, and to drink the restorative bromowater. By World War II, Michigan Chemical was splicing bromine and chlorine from these same deposits, turning them into a variety of hydrocarbon-based chemicals, and eventually into DDT.

The plant, tucked along the Pine River, was shuttered in the late 1970s. In the 1980s, it was interred in place. Twice it has been added to the federal Superfund list, the second time after the first attempt to cap and contain its contents failed. Now retired, Roslund, who’d grown up in the area, served on the Pine River Superfund Citizen Task Force. In the spring of 2016, the Task Force invited me and other environmental professionals to discuss the intergenerational inheritance of DDT and its consequences.

The DDT can he handed me was the size and shape of a soup can, with a white label and instructions for use in six of Europe’s languages. As traffic sped past and planes roared overhead, I circled my finger around the rusted lid’s soldered lip, tipped the can over, and felt its contents shift inside.

It was eerie to touch something most of us had relegated to the past! The United States restricted its major uses 50 years ago, in 1972, and by 2004, the United Nations had curtailed DDT use globally, save in malaria control.

But as I came to learn, for Roslund and his community, the book of DDT has never been closed. By the time I’d visited in 2016, the ambient soil levels of DDT were so high that St. Louis’s robins were convulsing, even dying, as if the parable that had opened Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, published in 1962, the year before Levi’s The Truce, had indeed come to fruition right in the middle of Michigan.

¤

Primo Levi and St. Louis both came to mind when I heard news of a new book about DDT, How to Sell a Poison, written by the medical historian Elena Conis, a professor of Journalism at the University of California at Berkeley. I had assumed Conis would plot out the wartime use of DDT, and perhaps explain how someone like Levi encountered it, and then proceed through DDT’s postwar boom and midcentury reckoning. And from this well-known history, the book, so I thought, might go on to add new chapters, bringing the DDT story into the 21st century by addressing, for instance, the decades-long remediation happening in places like St. Louis.

Or perhaps Conis would, I had imagined, uncover how scientists discovered that a mother’s or even grandmother’s DDT exposure can alter the life-course — and the breast cancer risk — of daughters and granddaughters.

Or, I’d thought, she might describe how geographers like Angeliki Balayannis track the migration of old DDT stockpiles across borders, which are loaded into incinerators, and then launched into a geochemical journey of another sort.

Or how UC Santa Barbara scientists documented the city-sized dump of drummed DDT production wastes in the waters off Southern California. The drums, found on the sea floor off Santa Catalina, one of the Channel Islands, had originated in Montrose Chemical’s DDT plant, built near Torrance in 1947. Only in 2019 did the drums make it into the scientific literature, and via the journalist Rosanna Xia, onto the front page of the Los Angeles Times.

Conis does indeed explore many of these issues, but what she attempts — and what she achieves — is more ambitious and unexpected: a wholesale rewrite of large swaths of DDT’s earlier chapters, highlighting new and different perspectives on how DDT was created, deployed, encountered, researched, promoted, and contested.

All too often, she writes, popular accounts of DDT history do not accord with the historical record. Yes, sing-song ads may have celebrated “DDT is good for me-e-e!” And even Dr. Seuss helped sell Flit!— Standard Oil’s version of the insecticide. But the story of how DDT moved into the civilian market is complicated. Its purported wholesale adoption by an ignorant or otherwise science-spangled public is a myth: it went into widespread use despite expert caution and consumer concern. The public was in fact already wary of pesticides, given the toxicity of earlier products. And long before Carson, military officials and even mainstream media advocated for selective DDT use so as not to disturb “the balance of nature.”

Conis consulted 30 different archives, some, as I understand it, new to DDT’s historiography, including the March of Dimes archives, which have since closed to the public. Her timing was serendipitous. What she uncovered there became critical to her narrative. In its documents, Conis learned that fear over polio’s spread — together with the well-intentioned efforts by public officials and the March of Dimes to do something to stop polio — promoted the citywide spraying of DDT before researchers had even ascertained whether polio was fly-borne. (It wasn’t.) And before it was known whether fogging city streets and raining DDT from retrofitted warplanes were effective methods of dispersal. (Again: It wasn’t.)

In sum: DDT “simply did not combat polio,” writes Conis. Eventually the foundation knew that it was at fault: its “publicity juggernaut had lifted public hopes for DDT.” It knew, too, that it had to reverse course without embarrassing itself. Not until 1950, however, did the March of Dimes divorce itself from DDT altogether, a position it published in FULL CAPS.

It was too late.

Despite evidence that DDT didn’t combat polio, and despite evidence of DDT-resistant “super flies,” towns continued to spray. The rationale: DDT, or so it seemed to some city officials, “helped calm persons who had become panicky over polio.”

This history is little known.

It was DDT’s premature deployment against polio, however, that conjured so many of the memorable images of this era: giddy white people enshrouded in a cloud of safe-keeping DDT. White children chasing DDT foggers. Or the image selected for Conis’s cover: a white, swimsuit-clad model with a burger and pop, DDT swirling around her. This image was an advertisement for the company that had made World War II smokescreen trucks, which in the polio frenzy had been retooled for deployment in the byways of American suburbia. These images are indeed iconic. But Conis’s larger point is that they are misunderstood. And they fail to tell the whole story around the public’s postwar ambivalence, nor around the uneven distribution of DDT’s implications.

¤

Because DDT history has been too narrow in its focus, Conis chooses to convene a chorus, or call it a disparate cacophony, of voices. Readers familiar with DDT history may recognize some of the players, but certainly not all of them. Rather than the Nobel Prize–winning Müller, for instance, Conis animates Victor Froelicher, the Swiss-born, US-based salesman for Geigy who downed a nugget of DDT in the US surgeon general’s office, a wartime ploy to convince the government the pesticide was safe for military use. “Dr. Froelicher,” the surgeon general had replied, “if you are alive tomorrow, you will be getting a big order from us.” He was indeed alive. Geigy scaled production of DDT for the US Army shortly thereafter.

In another example, Conis highlights those players who contested DDT before Carson even turned her formidable literary talent to the subject. Doffie Colson, for example, a petite Georgia farmer with a “heart-shaped face” and bun coiled atop her head, endeavored to start a movement against DDT not long after the war had ended. DDT, applied by war-planes-turned-crop-dusters to an adjacent property, she explained, threatened her cows, her chicks, her honeybees, her family, her livelihood. Colson railed against aerial spraying in letter after letter penned to state and federal officials. “Any poison strong enough to kill or damage honey bees,” she wrote, “is surely strong enough to affect people.” Colson was dismissed as anxious — a charge levied against women’s environmental health critiques across the 20th century, as environmental sociologists have noted. Her letters were filed and then archived until unearthed by Conis.

Another profile: Montessori-teacher-turned-organic-farmer Marjorie Spock (sister of renowned pediatrician Dr. Spock) funneled research and news clippings to Carson. Multiple biographers have profiled Carson, but Conis takes the slant approach, synthesizing the moment through Spock’s eyes, which then colored Carson’s. Through Spock, readers watch Carson as she stands before Congress and endures the industry’s vitriol, while in private she is succumbing to breast cancer.

The US’s DDT restrictions after Carson’s death are often “read as a moment that captures the ascent and power of environmentalism. But that account leaves out the economic forces at play behind the scenes,” argues Conis. DDT ceased being a lucrative product shortly after the war, and so most wartime manufacturers stopped production in the 1950s. By the 1970s, the industry favored newer patented, proprietary formulas, some of them potent and acute poisons like parathion.

Like the geographer Laura Pulido before her, Conis also highlights the pivotal role played by the farm workers’ movement. This is a story told through the young organizer, Jessica Govea, a gifted singer raised in the agricultural fields of California, who picked potatoes and plums alongside her parents. In the 1960s, Govea became instrumental in the United Farm Workers’ grape boycott, which helped secure safer working conditions, including from widespread exposure to a range of far more immediately acute pesticides, by organizing around DDT’s elevated public profile.

In all these descriptions of people and places, Conis, who holds degrees in both journalism and history, writes with a journalist’s clarity and remove, and a historian’s exacting fidelity to primary sources. She conveys her findings through narrative (more than through historical argument), with scenes rich in dialogue and description. “Narrative itself is argument,” the environmental historian Bathsheba Demuth said on the podcast, Drafting the Past. “How you tell a story is part of why the story matters, who comes first, who gets to speak?” What towns or places get profiled matters, too, and so it is no accident that Conis opens her book in Triana, Alabama, another town, like St. Louis, living out DDT’s long-tailed legacy. Triana, however, “became a battleground for a scientific dispute over just how toxic the banned chemical actually was.”

In the postwar era, Triana, then an unincorporated, predominantly Black community, sat downriver from another chemical factory that made DDT under government contract. In the 1960s, the US Army, on whose land the plant stood, knew DDT had contaminated the creekbed that flowed through the town, and that any fish taken from its waters contained DDT levels far too high to consume, though no one had alerted the town’s fisherfolk. For many residents, the river was a critical food source beyond the purview of the Food and Drug Administration, who had set, in this instance, “all but meaningless” limits — called “tolerances” — on how much DDT was allowable in the food supply. The Centers for Disease Control’s first tests found that the fish caught near Triana, explains Conis, had “DDT levels fifty times higher than what the FDA considered safe.”

Though other scholars, including the preeminent environmental justice scholars Robert Bullard and Dorceta Taylor, have written about Triana, Conis revisits the community — slantwise, again, compared to their renderings — by focusing on its former mayor, Clyde Foster, whom she brings to life using archival research and interviews with those who knew him.

Drawn to Alabama in the late 1950s to work at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency, Foster was struck by the racial segregation he experienced at work, and the gulf between his work preparing rockets for the lunar launch and the life of people in nearby Triana who lived “without electricity or running water.” Foster didn’t learn about the DDT contamination until the late 1970s, more than a decade after the military and other factions of the federal government knew just how much DDT was in the river and its fish. Foster stumbled on the story in the newspaper. As Conis explains, Foster was incensed, which rocketed him into a decades-long pursuit of recognition for the problem and its remediation. He did so in parallel with Lois Gibbs, who was contesting the toxic waste at Love Canal, which in stark contrast to the Triana contamination did inspire both national media attention and what became the Superfund Law. “If this community had been anything other than Black, the circumstances would have been different,” Foster concluded.

Conis revisits Triana in parts two and three, and in the final pages, where we meet Foster’s daughter mid-pandemic. Conis gives the late Foster, who died in 2012, the final word on DDT: “The issue transcends Triana and Indian Creek and the Tennessee River,” he said. “What we are talking about here is planet Earth. God only made one.”

Conis thus weaves an intricate tapestry in what is surely the book’s strength even as it poses a downside: because most chapters introduce a new community and variegated cast of characters, only a handful reappear as the narrative advances. There are thus a lot of discontinuous particulars to keep tabs on. I resorted to mapping the narrative in the book’s back blank pages, sketching out a rough-hewn map of the United States to better comprehend the importance of key people, organizations, place names, and dates.

But this is often the case in historical work. Archives, if they exist at all, typically offer discontinuous fragments from which the historian puzzles out what happened. Conis confines the story’s complexity by structuring her narrative around DDT’s linear chronology — its rise, fall, and reprise — and the familiarity of the three-act story. And in the end, the effect feels fitting: story upon story accumulates over the course of the book — like DDT on the riverbed, on the sea floor, in the human body.

¤

DDT belongs to a class of pesticides called organochlorines. Today, a new generation of pesticides is streaming into the economy: neonicotinoids, which are replacing the organophosphates that had replaced organochlorines, which had ousted their older arsenic-based predecessors. This succession of substitutions represents a broader pattern evident in industrial chemistry across the last century, when known toxics were replaced by un- or lesser-known variants, only to be removed from the market once their harms were better documented.

These “regrettable substitutions,” as scientists call them, happen within a company’s product offerings, too. In the early 1970s, with DDT off the market, Michigan Chemical pivoted from pesticides to flame retardants, which are applied to plastics to slow the spread of fire. In particular, the company pinned its future on polybrominated biphenyls (or PBBs), a replacement for polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), another family of troubled organochlorines.

“Continuing [its] past practices, Michigan Chemical expected to profit handsomely from PBBs — assuming it would bear none of the externalities,” writes historian Edward Lorenz, who also serves on the Pine River Superfund Citizen Task Force. As before, the company used the river to offload its prodigious wastes.

PBB went on to poison the whole of Michigan, as journalist Joyce Egginton put it. In 1974, workers confused PBB with another powdered product, a cattle feed additive. Distributed to farms across the state, PBB entered the meat and dairy supply. Like so many Michigan families, Roslund, who’d met me at the Detroit airport, lost his family’s herd as a result. Four generations later, scientists from Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health still track residents’ PBB blood levels and, as with DDT, are exploring multigenerational effects.

“This year we have crossed one of the foolish thresholds of [the PBB] issue here,” Lorenz wrote to me by email. “This year the half-billion clean-up of the old factory has lasted longer than the plant's entire years of operation.”

I remember touring the old Michigan Chemical site with Lorenz on an early spring evening. Across the river, the playground at Penny Park was empty. From the perimeter of the fenced-off, ghosted factory, I heard the sounds of dusk: engines cut followed by car doors and screen doors and kitchen pots set on the stove. Lorenz was joined by Jane Keon, another member of the Pine River Superfund Citizen Task Force, who explained how she and others had gotten the EPA to return after the first remediation plans had failed. Now the groundwater was being filtered. “We must teach our children never to turn off the pumps,” Keon had said.

But in the early 2000s, just as St. Louis organized for further help, headlines were calling for DDT’s revival for use against vector-borne diseases like malaria and West Nile Virus. Carson — and anyone who’d supported DDT’s restriction through the United Nations — was dismissed, or vilified, for sparing birds over children in under-resourced countries.

“Something in DDT’s twist of fate didn’t add up,” Conis remarked in a Twitter thread. “I carried the question of it around with me for another ten years, until I stumbled across what felt like a clue.”

That clue was in yet another unexpected archive: the tobacco industry documents, nearly 13 million of which were made public following the 1998 settlement of the government-led suit against the industry’s marketing tactics.

As Conis uncovered, “to sell one poison, in short, the tobacco industry sold a morality tale about another.” Using its version of the DDT story, a story about the harms of regulatory overreach, the tobacco industry deflected attention from mounting public and scientific concern over secondhand smoke, and in the process, “obliterated the US public’s trust in science.” Tobacco’s retelling of the DDT story “led us to the moment we’re now living in, a moment in which science is intensely polemical and politicized.”

“Our ideas about science,” she notes on Twitter, are “shaped by actors we didn’t even know were in the game.”

How DDT became entangled in tobacco politics is but one example of how DDT was deployed in what Conis calls “proxy battles.” DDT, she argues, was wrapped into malaria-eradication programs. It was a weapon through which militaristic colonialism was enacted or the Cold War waged, a “way to secure allegiance to capitalism” and limit the spread of both malaria and communism.

One can read How to Sell a Poison as a story about DDT, yes, but it is just as much a book about science and society, and how science is also “the turf on which we do battle over differences of gender, race, economic power, and more,” says Conis.

DDT didn’t make the comeback that had been coordinated by tobacco and other free-market interests, but the campaign did succeed in “seeding an idea” — that “an attack on science” was “useful to the Madison Avenue public relations executives […] creative in devising ways to exploit the need for verification and refutation in science.” Quoting journalist Paul Thacker, Conis says doubt and scientific misinformation are, like Levi’s and Coca-Cola, perhaps the most iconic American product of all, which is an idea that harkens to Primo Levi. Widespread application of DDT may have spared Naples from typhus during the war, and, who knows, may have spared Levi, too. By the time Levi was writing The Truce, he understood that DDT had become as potent a symbol of political power as it was a poison.

Earlier this year, an international team of scientists warned that the influx of novel entities into the planetary system — industrial outputs like DDT and other pesticides, along with PBBs and similar plastics-associated pollutants — now exceeds science’s capacity to assess the systemic changes already underway. What is at stake, they concluded, if industrial systems don’t rein in future production, is the capacity for the planet to support life. As Foster said in the book’s closing line: “God only made one.”

¤

Rebecca Altman is a Providence-based writer. She holds a PhD in environmental sociology from Brown University and is working on an intimate history of plastics for Scribner Books (US) and Oneworld (UK).

LARB Contributor

Rebecca Altman is a Providence-based writer. She holds a PhD in environmental sociology from Brown University and is working on an intimate history of plastics for Scribner Books (US) and Oneworld (UK). Her recent work on plastics and plastics-associated pollutants has appeared in The Atlantic, Orion Magazine, Science, Aeon, and The Washington Post.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Nobody Likes Dolphin Meat, but Times Are Hard

This story makes landfall, is beached, on April 4, 2021, but, really, the story begins earlier still: with the Atlantic Slave Trade and its long...

At Home in the Unseen World

Psychiatrist and historian George Makari remembers his father, Jack Makari, a pioneer of cancer immunology and microbiology.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!