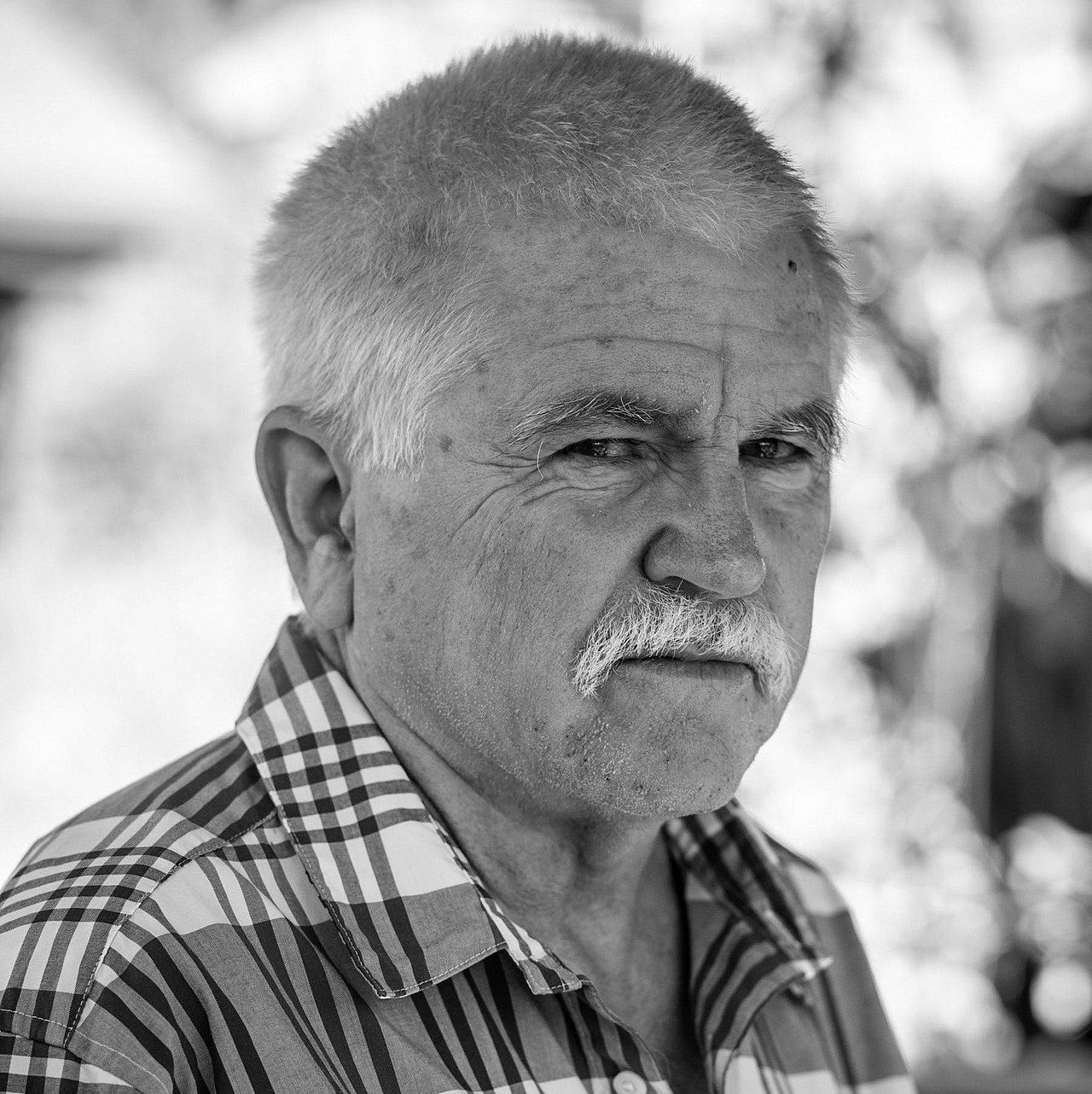

Remembering Mike Davis

Tributes to a giant of L.A. letters from his colleagues and students.

By David Kipen, Derrick Ortega, John Shannon, Matt Garcia, Peter Sebastian Chesney, William DeverellOctober 26, 2022

MATT GARCIA

In my time knowing Mike Davis, he often exhibited a healthy dose of suspicion towards, if not outright contempt for the Ivory Tower, especially for those he called “effete” intellectuals.

I met him in the last month of my fourth year at UC Berkeley. He was a guest in a California geography class taught by the great Dick Walker (no effete intellectual!). Mike spoke in his now-familiar monotone style, delivering a lecture about the place I grew up, the Inland Empire, a place I called East of East L.A. but many saw as a backwater of the metropolis. He spoke about the benefits that come from driving a truck or working a butcher line, the latter an experience I knew well from working in my father’s carinercía.

I sought him out after class, first at Cody’s Bookstore that evening, to hear him talk about City of Quartz. It was probably the first book I read front to cover without stopping. His closing chapter, “Junkyard of Dreams,” about Fontana, made me feel as if someone finally understood the hideous truth about Los Angeles, found in one of the city’s many sacrifice zones scattered across the Southland. I remember thinking, “If history can be written like this, I want to be a historian.”

I went to Claremont Graduate School mainly because Mike was teaching at Pitzer College. He taught a class, “Behind the Orange Curtain,” about the exploitative Jim/Juan Crow world of citrus colonies from San Gabriel to Riverside that inspired my first book. He was so generous with many of us at Claremont, making time for a “salon” where we read beyond the pirated collection of readings he had put together for the class (I still have it), and hosted local activists. I was lucky to belong to a collective that included Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Craig Gilmore, and a young Juan De Lara. Mike inspired us to write about our homes, our passion, and the institutions and places that shaped us. He taught us the value of getting out of the classroom, out of the archives, and into the community. He would tell us that the only histories worth their salt were those that had been written by authors who spoke to the people who lived them.

Many knew him as a prolific writer and a man who can expound on any subject, but I knew him also as a great listener. He listened with his eyes, staring intently at whoever shared their knowledge or an experience with him. When he first fixed his gaze on me, it unnerved me, but I eventually learned that it was his way of paying respect to you. He made me who I am today, and I am grateful for the time we shared together. Thank you, Mike.

¤

WILLIAM DEVERELL

My sister gave me a first edition Verso City of Quartz when it came out and before I even had heard of it. Years later, Mike signed it for me, and it is one of my prized books, one of my favorite possessions, actually.

I’ll remember the sign-offs, whether by email, quick note, or in an inscription. “In Struggle,” and he meant it. “Abrazos,” and he meant it. Mike never failed to ask after my two kids, and many of our conversations began and ended with him speaking of his children, wondering what mine were up to, smiling at this or that story. My wife and I, years before we were married, were walking hand in hand in Pasadena, and Mike drove by in his truck. He stopped, got out, smiled, and said, “Ah, young love. Restores your faith in all of us.” And then he drove away.

Oh, did he contain multitudes. The fierce intellect, the fearsomeness, the brusquely uncompromising activist scholar, the capacious mind. Mike taught me how to re-think most of what I thought about Southern California, to reframe it beyond the academy and its expectations, even its obligations. I thought I knew what oligarchy meant before Mike taught me deeper ways to understand it and, by extension, to understand modern L.A. And that’s true with so many categories of identity, analysis, and inquiry.

You wouldn’t immediately characterize Mike Davis as a nerd. But he had an innate fascination with the materiality of the past. Political buttons, IWW pamphlets, campaign documents of this or that Leftie or Leftie organization. He was the most interesting combination of antiquarian and politically committed manifesto-writing historian I’ll ever meet. He singlehandedly changed Southern California historiography, so much so that there’s a B.Q. (before Quartz) and an A.Q. (after Quartz) way to look at the field. Still.

The generosity and the sheer loyalty remain inspirations to me, always will, every bit as much as the trailblazing writing. Mike threw open his Pasadena garage and its filing cabinets to one of my wonderful graduate students decades ago. My student’s work explored early 20th-century Los Angeles and political activism. Through City of Quartz, Mike had led him to this topic every bit as much as I had done as his mentor. He set out to flesh out much that Mike had suggested, hinted at (though Mike hinting isn’t really quite right), offered up as breadcrumbs for someone following his lead.

My student’s research trail took him to Mike’s garage at his then-Pasadena home, with its multiple filing cabinets of historical documents, research notes, and those amazing artifacts he loved gathering up. “Look at anything, Mike said, “use anything, make yourself at home with all that is here.” It wasn’t a gesture, it was Mike.

¤

JOHN SHANNON

The big touchstones of Mike’s political activism, his editing at the New Left Review and his groundbreaking books and essays that dig out the hidden clockwork of his city and of world capitalism, are so well known that I’ll leave recounting them to others. Something else makes my eyes burn right now. Over and over I saw it: No matter how overcommitted Mike was, drowning in political fights and painstaking research that truly mattered, someone new to him would be directed into his orbit — young, uneducated, or as we sometimes say, lumpen — and Mike would drop his own work and focus with the intensity I know I’d save for Marx himself or Gandhi (okay, Mike — or Trotsky). Unfailingly courteous, no matter how “unimportant” or peripheral to the Big Picture this new arrival was.

Examples abound. After the Watts uprising of 1965, Mike worked at length with a streetwise Crip trying to broker a peace treaty between the gangs. In a remarkable but unreleased documentary, Shotgun Freeway, Mike spent precious screen time in an underground storm drain to talk up the work of a young street artist the camera showed covering the walls. At a large testimonial dinner run yearly by a progressive library Mike was to receive a “Movers and Shakers” Award. He brought with him and introduced around a student activist who, he said, should really be getting the award.

I was nobody when we met, just beginning to commit to social consciousness, and not yet writing political novels. Just a random guy. Mike was right there listening to me and taking me seriously, and he never stopped. My Southern California is a whole lot smaller now.

¤

PETER SEBASTIAN CHESNEY

A great theorist’s life has ended — and with it ends his fraught relationship with Southern California. Mike Davis was born to the Baby Boomer generation in the Inland Empire. He took an unconventional route into literary and academic fame. Reed College expelled him, UCLA’s history department denied him a doctorate for a dissertation called City of Quartz, and the Los Angeles Times ran an exposé alleging he was a fabulist. But he drove around those roadblocks.

In the 1980s, he began publishing in the United Kingdom. The UCLA historians’ refusal to sign off on City of Quartz did not deter Davis from submitting it to Verso, complete with enigmatic title. He thought of Los Angeles as a crystal ball where you can see the earliest signs of what capitalism has in store for other parts of the United States and the world. Today, City of Quartz is the most cited book about Los Angeles on Google Scholar.

After several years of disengagement with Los Angeles in favor of more global concerns, Davis co-wrote Set the Night on Fire with cultural historian Jon Wiener. This encyclopedic account of the bottom-up social history of Los Angeles in the 1960s has overturned the increasingly narrow historiography of the region at that time. Academia has tended only to reward scholars with tenure who write obscure microhistories. The result is a fragmented literary landscape that renders Southern California illegible to all but the most avid and open-minded readers. With Mike Davis at your bedside, you can be sure that you will not fall into such provincialisms.

My mentors in the UCLA history department found many excuses to dismiss Davis. Some hated him for his spotty footnotes. Others thought he reified class dynamics and minimized racial identity or aesthetic achievement. The hardest critique to rebut came from feminist history, which noted the near invisibility of gender and sexuality in his work. He went mildly viral recently for declaring himself an “old school socialist” — by which he meant a realist who was always open to renegotiation and contingency.

¤

DAVID KIPEN

Reading City of Quartz today is a very different experience from when Verso first had the guts to publish it. Back then, reading Mike Davis felt like discovering some long-lost teacher’s edition of Los Angeles. He knew where the bodies were buried, and precisely who had buried them. He knew this because he’d read seemingly everything in Christendom, and with total photographic recall — from pulp novels barely even in print the first time around to enough critical theory to put the “hork” into Horkheimer and Adorno.

City of Quartz belongs on a tiny list of books that any new Los Angeles Times opinion editors should absolutely read before they report to work. They could run any two merciless pages of it in this Sunday’s paper, and no reader would find them dated. A lot of City of Quartz could have been published yesterday. People still die in Los Angeles every day for no damn good reason, and all the bike lanes in the world won’t change that.

Does all of City of Quartz hold up? I’m not even sure I want it to. Every great work of history records its own time as much as any other. This is not only inevitable, but desirable. Edward Gibbon tells us as much about Georgian England as he does about Ancient Rome, and who would wish it otherwise? Mike Davis has given us a deeper revisionist history of L.A. than anybody since Carey McWilliams, but his masterpiece also helps us know what it felt like to live in L.A. specifically in 1990 and smell a riot coming.

I’d go even further. Without the warning shot heard in City of Quartz, we might just be living in the future Davis predicted. The book may even be that rare thing: a self-averting prophecy.

¤

DERRICK ORTEGA

The first time that I truly spoke with Mike was in his creative nonfiction workshop at the University of California, Riverside, where he had 15 of us assembled in a circle (fairly standard), though he didn’t sit along the circle but inside of it (new to me). He would place a chair in front of each student and begin to have a direct conversation to get at the heart of the writer. As Mike moved from writer to writer, getting into the rhythm of his voice felt more and more like an invitation to craft and concept.

When it was finally my turn, he slid his chair over from the previous chat, postured up before leaning forward (we’re talking almost less than a foot away), and, with a direct stare, he just waited. None of us had to count in our heads to identify what started to feel like a long time, yet he was adamant in his patience.

The best way I can describe it was the look of curiosity — just wanting to listen for the sake of listening. Even at a point in his career when his accumulated wealth of research, experience, social interaction, and considerations was arguably second to none, he was still tightly gripping that piece of himself that drove him to the writer’s life.

I started reading my poems out loud. When I was done, he neither gave praise nor feedback for revision. After that day, I made sure to see him for office hours as many times as possible and, without fail, he would proceed in the same manner each time, allowing what felt like a cyclical dynamic to provide my own personal opportunity for breakthrough in conversation.

He’d close each session with an invitation to visit him at his home a few hours away in San Diego, always mentioning that the light is always on.

¤

Matt Garcia is a professor of History and Latin American, Latino, and Caribbean Studies at Dartmouth College and the author of A World of Its Own: Race, Labor, and Citrus in the Making of Greater Los Angeles, 1900-1970 (2001) and From the Jaws of Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement (2012).

William Deverell is a professor of History, Spatial Sciences and Environmental Studies at USC, the director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West, and the author, most recently, of Kathy Fiscus: A Tragedy that Transfixed the Nation (2021).

John Shannon is the author of The Concrete River and many other novels in and out of the Jack Liffey detective series.

Peter Sebastian Chesney is the author of Drive Time: A Sensory History of Car Cultures from 1945 to 1990 in Los Angeles (2021).

David Kipen is the author of several books, among his recent the anthology Dear Los Angeles: The City in Diaries and Letters. His fiction and nonfiction has appeared in The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times.

Derrick Ortega is an instructor in Creative Writing at Chapman University and Orange County School of the Arts.

LARB Contributors

David Kipen is the author of several books, among his recent the anthology Dear Los Angeles: The City in Diaries and Letters. His fiction and nonfiction has appeared in The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times.

Derrick Ortega is an instructor in Creative Writing at Chapman University and Orange County School of the Arts.

John Shannon is the author of the critically acclaimed Jack Liffey detective novels, including The Concrete River (1996), The Cracked Earth (1999), The Orange Curtain (2001), Terminal Island (2004), and A Little Too Much (2011). He has also written a three-generation saga novel of the American Left — Socialist, Communist, New Left — called The Taking of the Waters, originally published by John Brown Books in 1994, and now available on Amazon as an eBook. www.jackliffey.com

Matt Garcia is a professor of History and Latin American, Latino, and Caribbean Studies at Dartmouth College and the author of A World of Its Own: Race, Labor, and Citrus in the Making of Greater Los Angeles, 1900-1970 (2001) and From the Jaws of Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement (2012).

Peter Sebastian Chesney earned his PhD in history from UCLA. He is a historical consultant and a visiting professor at Pepperdine University.

William Deverell is the director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!